South African Class 16C 4-6-2

|

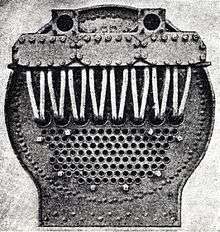

Class 16C no. 825, as built, with Belpaire firebox | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| As built, the 2nd coupled axle had flangeless wheels | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The South African Railways Class 16C 4-6-2 of 1919 was a steam locomotive.

During 1919, the South African Railways placed ten Class 16C steam locomotives with a 4-6-2 Pacific type wheel arrangement in passenger train service. Another twenty entered service in 1922. Unlike the earlier Classes 16 and 16B, these locomotives had combustion chambers.[1][2][3][4]

Manufacturer

The Class 16C 4-6-2 Pacific type locomotive was designed by D.A. Hendrie, Chief Mechanical Engineer (CME) of the South African Railways (SAR), and built by the North British Locomotive Company (NBL) in Glasgow, Scotland. Ten locomotives were delivered in 1919, numbered in the range from 812 to 821. A second order followed in 1921 for another twenty locomotives, which were numbered in the range from 822 to 841 when they were delivered in 1922.[5]

Characteristics

They were identical to predecessors Classes 16 and 16B in most respects, except that Hendrie had added a combustion chamber to the boiler, similar to that of the Class 15A. This reduced the distance between tube plates from 18 feet 3 inches (5,563 millimetres) to 15 feet 10 1⁄2 inches (4,839 millimetres). The presence of the combustion chamber was visible externally as an extension of the Belpaire firebox hump.[2][5]

The engines were equipped with Lambert sanding gear, which was a "wet" system whereby a mixture of water and sand was delivered to the rails. Under ideal conditions with fine-grained sand, results were fairly good, but maintenance problems and cost led to reversion to gravity sanding on later engines.[2]

The boilers were fitted with the Robinson type superheater, the first time this type was used on a Hendrie engine. The Robinson header was constructed with compartments, alternately for saturated and superheated steam. There were eight inlet and outlet ends of superheater elements expanded into the bottom wall of each compartment, with the exception of those compartments at each end, into which only three element ends were expanded. Three cover plates were bolted to the front of the header to allow access to the respective compartments, for expanding the element tubes in position or forcing them out when necessary.[2]

Modifications

Coupled wheels

During 1937, the Class 16C engines were fitted with Stone-Deuta speed indicators. As built, the second coupled axle had flangeless wheels, but these were later retyred with flanges, with the object to obtain better distribution of tyre flange wear and improved running.[2]

Like the subsequent Classes 16D and 16DA, the Class 16C locomotives were all delivered with 60 inches (1,524 millimetres) diameter coupled wheels. Their as-delivered boiler operating pressure was set at 190 pounds per square inch (1,310 kilopascals). During 1936, their coupled wheel diameter was enlarged to 63 inches (1,600 millimetres), similar to the modification which was also done on some Classes 16D and 16DA locomotives. In the process, their boiler operating pressure was raised to 200 pounds per square inch (1,380 kilopascals) in order to not have their tractive effort reduced by the larger coupled wheels.[2][6][7]

Trofimoff piston valves

During 1931, A.G. Watson, CME of the SAR at the time, fitted engine no. 851 with Trofimoff type by-pass piston valves as an experiment. The Trofimoff valve was claimed to afford ideal conditions when drifting.[2]

It consisted of two fixed discs, secured to the valve spindle, and two junk rings, each carrying a Bull ring and four valve rings and both free to move longitudinally on the spindle. When the regulator is opened, steam forces the loose valve bodies against their respective fixed discs, and they then act as units similar to ordinary piston valves. When steam is shut off, the loose valve heads become detached from their respective discs and remain in their idle positions near the centre of the steam chest, while the valve spindle and fixed disks continue their reciprocating motion, with the spindle sliding freely through the now stationary loose valve heads, and with the steam and exhaust ports now in communication. With both ends of the cylinders now in communication, the use of ordinary by-bass or snifting valves became unnecessary.[2]

Further similar experiments were carried out on Class 5B no. 726 in September 1931, Class 16B no. 805 in July 1932, Class 16DA no. 876 in August 1932, Class 15CA no. 2852 in March 1933 and finally on Class 15A no. 1961. The results of these extended tests did not prove entirely satisfactory and all these engines were gradually refitted with standard piston valves and snifting valves.[2]

Watson Standard boilers

During the 1930s, many serving locomotives were reboilered with a standard boiler type, designed by A.G. Watson as part of his standardisation policy. Such Watson Standard reboilered locomotives were reclassified by adding an "R" suffix to their classification.[5][6][7]

Eventually all thirty Class 16C locomotives were reboilered with Watson Standard no. 2B boilers and reclassified to Class 16CR. Several alterations to the engine frames were necessary to accommodate the no. 2B boiler. Bearing brackets had to be provided on the bridle casting to suit the firebox support sliding shoes, fitted at the front of the firebox foundation ring. The frame had to be altered to suit the new wider Watson cab, with its slanted front to allow access to the lagging which covered the flexible stays and stay caps on the firebox sides.[2]

A steam operated firedoor was fitted, permitting the stoker to operate the door by means of a foot treadle, while an auxiliary operating handle allowed the driver to operate the door in situations where this was found more convenient. The ashpan was attached to the engine frame instead of to the boiler, to enable the boiler to be removed from the frame without disturbing the ashpan, an innovation which became standard practice on the SAR.[2]

Their original Belpaire boilers were fitted with Ramsbottom safety valves, while the Watson Standard boiler was fitted with Pop safety valves. Early conversions were equipped with copper and later conversions with steel fireboxes. After reboilering, the main difference between the Class 16B and Class 16C, Hendrie's combustion chamber behind the Class 16C's boiler, disappeared and Class 16B locomotives which were reboilered with Watson Standard boilers were also reclassified to Class 16CR.[5][6][7]

An obvious difference between an original and a Watson Standard reboilered locomotive is usually a rectangular regulator cover, just to the rear of the chimney on the reboilered locomotive. In the case of the Class 16C and Class 16CR, two even more obvious differences are the Watson cab and the absence of the Belpaire firebox hump between the cab and boiler on the reboilered locomotives.[2][6][7]

Service

The Class 16C proved to be excellent locomotives which were popular with the locomotive crews, being free-steaming, fast, reliable, with quick acceleration and a reserve of power greater than that of either the Class 16 or Class 16B. On one occasion in 1922, one of them, working between Bloemfontein and Kroonstad, hauled a train of eighteen mainline saloons, a load which would have been considered good for the much more modern Class 15F of 1938.[1][2]

South African Railways

The Class 16C Pacifics were placed in express passenger service, working out of Pretoria and Johannesburg, hauling all the important passenger trains of the time, such as the Natal mail train on the section between Johannesburg and Volksrust and the Cape mail train on the section between Johannesburg and Klerksdorp. When they were replaced by newer locomotives like the Class 16D, they were relegated to less glamorous passenger duties until, by the 1940s, they were in suburban and transfer service.[1][5]

During the 1950s, some were relocated to Durban to assist the Class 14Rs on the South Coast line. When this line was electrified in 1967, they were again relocated, this time to Port Elizabeth, where they worked suburban trains to Uitenhage.[5]

Others remained on the Witwatersrand, working the suburban to Springs and Nigel, double-heading with Class 15ARs on Pietersburg-bound trains out of Pretoria, as well as shunting and local pick-up duties. Some of their last passenger duties were on the Breyten line during 1967 and 1968.[5]

They were sure-footed enough to take to shunting work as readily as to the fast passenger service which they were originally designed for, to the extent that some of their last duties at the Springs shed was to take over shunting duties from the Class S2 shunting locomotives. They were withdrawn from service between 1975 and 1976, with some being sold to start a second career in industrial service.[4][5]

Industry

Two Class 16CRs, numbers 813 and 818, were sold to Dunn's Locomotive Works, to be employed at Delmas Colliery, and were at one time seconded to Durban Navigation Collieries (Durnacol) in Natal. No. 838 went to Klipfontein Organic Products and later to the St Helena Gold Mine, and five went directly to the St Helena Gold Mine. At St Helena they were, as best as could be ascertained, renumbered as shown in the table below:[4]

| SAR No. |

SHGM No. |

|---|---|

| 815 | 6 |

| 817 | 5 |

| 819 | 2 |

| 821 | 1 |

| 838 | 3 |

| 839 | 4 |

Illustration

The main picture and those following offer views of the Class 16C locomotive before reboilering, with the original cab, and the Class 16CR after reboilering, with the Watson cab.

_(1).jpg) NBL builders's picture of Class 16C no. 823, c. 1921

NBL builders's picture of Class 16C no. 823, c. 1921.jpg) Class 16C no. 823 before reboilering, c. 1930

Class 16C no. 823 before reboilering, c. 1930 Class 16CR no. 840 at De Aar, 1978

Class 16CR no. 840 at De Aar, 1978_Durban_Navigation_Dannhauser_110479.jpg) Class 16CR no. 813 as Durnacol no. 2, Dannhauser, 1979

Class 16CR no. 813 as Durnacol no. 2, Dannhauser, 1979_St.Helena_Gold_Mine_050581.jpg) Class 16CR no. 821 as St Helena Gold Mine no. 1, 1981

Class 16CR no. 821 as St Helena Gold Mine no. 1, 1981

References

- 1 2 3 Holland, D.F. (1972). Steam Locomotives of the South African Railways, Volume 2: 1910-1955 (1st ed.). Newton Abbott, Devon: David & Charles. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7153-5427-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Espitalier, T.J.; Day, W.A.J. (1945). The Locomotive in South Africa - A Brief History of Railway Development. Chapter VII - South African Railways (Continued). South African Railways and Harbours Magazine, September 1945. pp. 674-675.

- ↑ North British Locomotive Company works list, compiled by Austrian locomotive historian Bernhard Schmeiser

- 1 2 3 Durrant, A E (1989). Twilight of South African Steam (1st ed.). Newton Abbott, London: David & Charles. pp. 92–93. ISBN 0715386387.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Paxton, Leith; Bourne, David (1985). Locomotives of the South African Railways (1st ed.). Cape Town: Struik. pp. 10–11, 65–66. ISBN 0869772112.

- 1 2 3 4 South African Railways & Harbours/Suid Afrikaanse Spoorweë en Hawens (15 Aug 1941). Locomotive Diagram Book/Lokomotiefdiagramboek, 3'6" Gauge/Spoorwydte. SAR/SAS Mechanical Department/Werktuigkundige Dept. Drawing Office/Tekenkantoor, Pretoria. p. 43.

- 1 2 3 4 South African Railways & Harbours/Suid Afrikaanse Spoorweë en Hawens (15 Aug 1941). Locomotive Diagram Book/Lokomotiefdiagramboek, 2'0" & 3'6" Gauge/Spoorwydte, Steam Locomotives/Stoomlokomotiewe. SAR/SAS Mechanical Department/Werktuigkundige Dept. Drawing Office/Tekenkantoor, Pretoria. pp. 6a-7a, 41, 43.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to South African Class 16C (4-6-2). |

.jpg)