Turtle (submersible)

Turtle (also called American Turtle) was the world's first submersible with a documented record of use in combat. She was built in Old Saybrook, Connecticut in 1775 by American David Bushnell as a means of attaching explosive charges to ships in a harbor. Bushnell designed her for use against British Royal Navy vessels occupying North American harbors during the American Revolutionary War. Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull recommended the invention to George Washington; although the commander-in-chief had doubts, he provided funds and support for the development and testing of the machine.

Several attempts were made using Turtle to affix explosives to the undersides of British warships in New York Harbor in 1776. All failed, and her transport ship was sunk later that year by the British with the submarine aboard. Bushnell claimed eventually to have recovered the machine, but its final fate is unknown. Modern replicas of Turtle have been constructed; the Connecticut River Museum, the U.S. Navy's Submarine Force Library and Museum, the Royal Navy Submarine Museum and the Oceanographic Museum (Monaco) have them on display.

Development

In the early 1770s, David Bushnell, a Yale College freshman and Patriot, began experimenting with underwater explosives. By 1775, with tensions on the rise between the Thirteen Colonies and Great Britain, Bushnell had practically perfected these explosives.[2] That year he also began work near Old Saybrook, Connecticut on a small manned submersible craft capable of affixing such a charge to the hull of a ship. The charge would then be detonated by a clockwork mechanism that released a musket firing mechanism, probably a flintlock, adapted for the purpose.[3] According to Dr. Benjamin Gale, a doctor who taught at Yale, the firing mechanism and other mechanical parts of the submarine were manufactured by a New Haven clockmaker named Isaac Doolittle.[4]

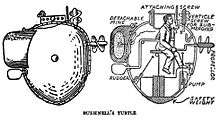

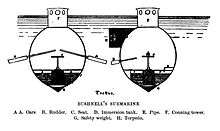

Named for its shape, Turtle resembled a large clam as much as a turtle; it was about 10 feet (3.0 m) long (according to the original specifications), 6 feet (1.8 m) tall, and about 3 feet (0.9 m) wide, and consisted of two wooden shells covered with tar and reinforced with steel bands.[5] It dived by allowing water into a bilge tank at the bottom of the vessel and ascended by pushing water out through a hand pump. It was propelled vertically and horizontally by hand-cranked propellers. It also had 200 pounds (91 kg) of lead aboard, which could be released in a moment to increase buoyancy. Manned and operated by one person, the vessel contained enough air for about thirty minutes and had a speed in calm water of about 3 mph (2.6 kn; 4.8 km/h).[5]

Six small pieces of thick glass in the top of the submarine provided natural light.[5] The internal instruments had small pieces of bioluminescent foxfire affixed to the needles to indicate their position in the dark. During trials in November 1775, Bushnell discovered that this illumination failed when the temperature dropped too low. Although repeated requests were made to Benjamin Franklin for possible alternatives, none was forthcoming, and Turtle was sidelined for the winter.[6]

Bushnell's basic design included some elements present in earlier experimental submersibles. The method of raising and lowering the vessel was similar to that developed by Nathaniel Simons in 1729, and the gaskets used to make watertight connections around the connections between the internal and external controls also may have come from Simons, who constructed a submersible based on a 17th-century Italian design by Giovanni Alfonso Borelli.[7]

Preparation for use

Bushnell's work began to receive more attention in August 1775, when Franklin was informed of it.[3] Despite Bushnell's insistence on secrecy surrounding his work, news of it quickly made its way to the British, abetted by a Loyalist spy working for New York Congressman James Duane. On November 16, 1775, a coded message to William Tryon, the last royal governor of the Province of New York, brought Bushnell's work to British attention. The details of the report were highly inaccurate, implying Turtle was nearly ready to be deployed in Boston harbor against the fleet that was part of the British siege effort there. In fact, Bushnell and his brother Ezra were still testing the machine in the Connecticut River.[8] In the spring of 1776, after the British withdrew from Boston, Bushnell offered the submarine to General George Washington for use in the defense of New York City. Washington agreed, and provided some funding to the inventor to prepare the vessel for deployment.[9]

In August 1776, Bushnell asked General Samuel Holden Parsons for volunteers to operate Turtle, because his brother Ezra, who had been its operator during earlier trials, was taken ill.[10] Three men were chosen, and the submersible was taken to Long Island Sound for training and further trials.[11] While these trials went on, the British gained control of western Long Island in the August 27 Battle of Long Island. Since the British now controlled the harbor, Turtle was transported overland from New Rochelle to the Hudson River.[11]

Attack on Eagle

General Washington then authorized an expedition by Turtle in New York Harbor.[12] At 11:00 PM on September 6,[1] one of the volunteers, Sergeant Ezra Lee, took the Turtle out to attempt an attack on Admiral Richard Howe's flagship, HMS Eagle,[11] then moored off Governors Island.[13]

According to Lee's account, Turtle was towed by rowboats as close as was felt safe to the British fleet. He then navigated for more than two hours before slack tide made it possible to reach Eagle. His first attempt to attach the explosive failed because the screw struck a metal impediment.[1] Lee tried and tried to turn the drill, but could not achieve penetration. A popular story held that he failed due to the copper lining covering the ship's hull. The Royal Navy had recently began installing copper sheathing on the bottoms of their warships to protect from damage by woodworms and other marine life, however the lining was paper-thin and could not have stopped Lee from drilling through it. Bushnell believed Lee's failure was probably due to an iron plate connected to the ship's rudder hinge.[14] When Lee attempted another spot in the hull, he was unable to stay beneath the ship, and eventually abandoned the attempt. It seems more likely that he was suffering from fatigue and carbon dioxide inhalation, which made him confused and unable to properly carry out the process of drilling through the Eagle's hull. Lee reported British soldiers on Governors Island spotted the submersible and rowed out to investigate. He then released the charge (which he called a "torpedo"), "expecting that they would seize that likewise, and thus all would be blown to atoms."[14] Suspicious of the drifting charge, the British retreated back to the island. Lee reported that the charge drifted into the East River, where it exploded "with tremendous violence, throwing large columns of water and pieces of wood that composed it high into the air."[14] It was the first recorded use of a submarine to attack a ship;[7] however, the only records documenting it are American. British records contain no accounts of an attack by a submarine or any reports of explosions on the night of the supposed attack on HMS Eagle.[15]

According to British naval historian Richard Compton-Hall, the problems of achieving neutral buoyancy would have rendered the vertical propeller useless. The route Turtle would have had to take to attack Eagle was slightly across the tidal stream which would, in all probability, have resulted in Lee becoming exhausted.[15] In the face of these and other problems, Compton-Hall suggests the entire story was fabricated as disinformation and morale-boosting propaganda, and if Lee did carry out an attack it was in a covered rowing boat rather than Turtle.[15]

Aftermath

On October 5, Sergeant Lee again went out in an attempt to attach the charge to a frigate anchored off Manhattan. He reported the ship's watch spotted him, so he abandoned the attempt. The submarine was sunk some days later by the British aboard its tender vessel near Fort Lee, New Jersey. Bushnell reported salvaging Turtle, but its final fate is unknown.[16] Washington called the attempt "an effort of genius", but "a combination of too many things was requisite" for such an attempt to succeed.[17]

Replicas

Functional replicas of the Turtle have been created and tested, as well as non-functioning cutaway ones for museum displays.

In 1976, a replica of Turtle was designed by Joseph Leary and constructed by Fred Frese as a project marking the United States Bicentennial. It was christened by Connecticut's governor, Ella Grasso, and later tested in the Connecticut River. This replica is owned by the Connecticut River Museum.[18]

On August 3, 2007 three men were stopped by police while escorting and piloting a replica of Turtle within 200 feet (61 m) of RMS Queen Mary 2, then docked at the cruise ship terminal in Red Hook, Brooklyn. The replica was created by New York artist Philip "Duke" Riley and two residents of Rhode Island, one of whom claimed to be a descendant of David Bushnell. The Coast Guard issued Riley a citation for having an unsafe vessel, and for violating the security zone around Queen Mary 2.[19]

In 2015, replicas of the exterior and interior of Turtle were used in the television series TURN: Washington’s Spies.[20][21]

Image gallery

1976 functional replica that is now at the Connecticut River Museum

1976 functional replica that is now at the Connecticut River Museum Cutaway replica at the Submarine Force Library and Museum, Groton, Connecticut

Cutaway replica at the Submarine Force Library and Museum, Groton, Connecticut- Cutaway replica at the Oceanographic Museum, Monaco

2007 functional replica created by Philip "Duke" Riley

2007 functional replica created by Philip "Duke" Riley

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Rindskopf et al, p. 30

- ↑ Diamant, p. 21

- 1 2 Diamant, p. 22

- ↑ Diamant, p. 23

- 1 2 3 Schecter, p. 172

- ↑ Diamant, p. 27

- 1 2 Rindskopf et al, p. 29

- ↑ Diamant, p. 26

- ↑ DANFS Turtle I

- ↑ Diamant, p. 30

- 1 2 3 Schecter, p. 173

- ↑ Shecter, p. 171

- ↑ Diamant, p. 31

- 1 2 3 Schecter, p. 174

- 1 2 3 Compton-Hall, pp. 32–40

- ↑ Diamant, p. 33

- ↑ Diamant, p. 34

- ↑ Connecticut River Museum – David Bushnell's Turtle

- ↑ Makeshift submarine found in East River

- ↑ TURN: Washington’s Spies

- ↑ TURN: Turtle Submarine

References

- Coggins, Jack (2002). Ships and Seamen of the American Revolution. Mineola, NY: Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-42072-1. OCLC 48795929.

- Compton-Hall, Richard (1999). The Submarine Pioneers. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2154-4.

- Diamant, Lincoln (2004). Chaining the Hudson: The Fight for the River in the American Revolution. New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-2339-8. OCLC 491786080.

- Rindskopf, Mike H; Naval Submarine League (U.S.); Turner Publishing Company staff; Morris, Richard Knowles (1997). Steel Boats, Iron Men: History of the U.S. Submarine Force. Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56311-081-8. OCLC 34352971.

- Schecter, Barnet (2002). The Battle for New York. New York: Walker. ISBN 0-8027-1374-2.

- Sleeman, Charles (1880). Torpedoes and torpedo warfare. Portsmouth, UK: Griffin. OCLC 4041073.

- "Turtle I". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- "Connecticut River Museum – David Bushnell's Turtle". Connecticut River Museum. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- "Makeshift submarine found in East River". WABC-TV. 2007-08-03. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- "TURN: Washington's Spies – Spycraft Handbook – The Turtle". TURИ: Washington’s Spies. AMC. May 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- "TURN: Turtle submarine". TURИ to a historian. June 4, 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bushnell Turtle (submarine, 1775). |