Raid on Unadilla and Onaquaga

The Raid on Unadilla and Onaquaga was a series of military operations by Continental Army forces and New York militia against the Iroquois towns of Unadilla and Onaquaga in what is now upstate New York. In early October 1778, more than 250 men under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William Butler of the 4th Pennsylvania Regiment descended on the two towns (which had been abandoned because of their advance) and destroyed them, razing most of the buildings and taking or destroying provisions. The raid was executed in retaliation for a series of raids on frontier communities led by Mohawk chief Joseph Brant and British-supported Loyalists during the spring and summer of 1778. Unadilla was located in what is now the Village of Unadilla, Town of Unadilla, Otsego County, and Onaquaga was located in what is now the Town of Windsor, Broome County.

Background

With the failure of British General John Burgoyne's campaign to the Hudson after the Battles of Saratoga in October 1777, the American Revolutionary War in upstate New York became a frontier war.[1] British leaders in the Province of Quebec supported Loyalist and Native American partisan fighters with supplies and armaments.[2] During the winter of 1777–78 Mohawk leader Joseph Brant and other British-allied Indians developed plans to attack frontier settlements in New York and Pennsylvania.[3] In February 1778 Brant established a base of operations at Onaquaga (present-day Windsor, New York). He recruited a mix of Iroquois and Loyalists estimated to number between two and three hundred by the time he began his campaign in May.[4][5][6] One of his objectives was to acquire provisions for his forces and those of John Butler, who was planning operations in the Susquehanna River valley.[7] Brant began his campaign in late May with a raid on Cobleskill, and raided other frontier communities throughout the summer.[8]

The frontier settlers' response to the raids was generally with impotence. The local militia were supported by some Continental Army regiments stationed in the area, but these forces generally could not muster in time to catch the raiders before they disappeared.[9] New York Governor George Clinton and militia commander Abraham Ten Broeck considered operations against the principal bases in the Iroquois territory used by the raiders, Onaquaga and Unadilla, early in the campaign, but it was not until an attack by Brant on the settlement of German Flatts (present-day Herkimer) on September 17 that an expedition was organized.[10]

In response to calls from Governor Clinton, General George Washington authorized the use of Continental Army forces, assigning the operation to Lieutenant Colonel William Butler (no relation to the Loyalist Butlers) of the 4th Pennsylvania Regiment.[11] On September 20 Butler sent scouts to investigate conditions at the two towns. They returned with reports that Unadilla had a population of 300 and Onaquaga 400.[12]

Expedition

On October 2 Butler led a force of 267 men (214 Continentals and 53 state militia) from Fort Schoharie up the Schoharie valley toward the two villages.[11] Late in the day on October 6 the force reached the Unadilla area. Butler sent scouting parties out to take prisoners from outlying farms. As the force cautiously advanced toward the town, one of the scouts returned with a prisoner who reported that the community had been abandoned, with most of the inhabitants fleeing to Onaquaga.[12] Butler detached some of his men to destroy the town while he marched with the rest toward Onaquaga. They reached the town late on October 8, and found it abandoned also, apparently in great haste.[11]

Butler and his men spent the next two days destroying the towns. Butler described Unadilla as "the finest Indian town I ever saw; on the both sides of the River there was about 40 good houses, Square logs, Shingles & stone Chimneys, good Floors, glass windows &c."[13] All the homes were burned, as was the town's saw and grist mill, which was the only one in the area. Butler reported taking 49 horses and 52 head of cattle, and destroyed 4,000 bushels of grain.[14] Operations were complicated by heavy rains that raised the water levels of the Susquehanna; Butler's men had to build rafts to cross some of the river's tributaries to reach parts of the town. By October 16 the expedition returned to Schoharie.[15]

Aftermath

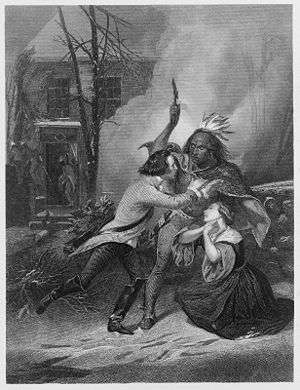

While the raid was taking place, Brant and his force had been raiding frontier settlements in the upper Delaware River valley.[16] The Indians in his force were especially upset at the destruction of the two towns, a sentiment echoed by Seneca warriors who joined with Brant in the ruins of Unadilla a few days later. This anger contributed to the severity of the actions when a joint British-Seneca-Mohawk force attacked Cherry Valley, and were reported to massacre 30 noncombatants.[17]

The severity of the frontier war in 1778 led to calls by the Continental Congress for a response.[18] In 1779 General Washington organized a major Continental Army expedition into the Iroquois lands. Led by Generals John Sullivan and James Clinton, the Sullivan Expedition destroyed villages and crops, driving most of the British-supporting Iroquois out of their lands. Despite its apparent success, the frontier war continued with renewed vigor in the following years.[19]

Notes

- ↑ Graymont, pp. 155–156

- ↑ Kelsay, p. 212

- ↑ Graymont, p. 160

- ↑ Barr, p. 150

- ↑ Kelsay, p. 216

- ↑ Graymont, p. 165

- ↑ Halsey, p. 207

- ↑ Graymont, pp. 165–167

- ↑ Halsey, pp. 207–217

- ↑ Barr, p. 151

- 1 2 3 Barr, p. 152

- 1 2 Halsey, p. 234

- ↑ Graymont, p. 181

- ↑ Halsey, pp. 235–236

- ↑ Graymont, p. 182

- ↑ Halsey, p. 237

- ↑ Barr, pp. 153–154

- ↑ Graymont, p. 192

- ↑ Barr, pp. 155–161

References

- Barr, Daniel (2006). Unconquered: the Iroquois League at War in Colonial America. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-98466-3. OCLC 260132653.

- Graymont, Barbara (1972). The Iroquois in the American Revolution. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0083-1. OCLC 34210182.

- Halsey, Francis Whiting (1902). The Old New York Frontier. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. OCLC 7136790.

- Kelsay, Isabel Thompson (1986). Joseph Brant, 1743–1807, Man of Two Worlds. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0208-8. OCLC 13823422.