Thylacoleo

| Thylacoleo Temporal range: late Pliocene—late Pleistocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of a Thylacoleo carnifex in the Victoria Fossil Cave, Naracoorte Caves National Park | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | †Thylacoleonidae |

| Genus: | †Thylacoleo Owen, 1859 |

| Species | |

| |

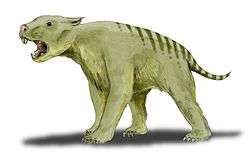

Thylacoleo ("pouch lion") is an extinct genus of carnivorous marsupials that lived in Australia from the late Pliocene to the late Pleistocene (2 million to 46 thousand years ago). Some of these "marsupial lions" were the largest mammalian predators in Australia of that time, with Thylacoleo carnifex approaching the weight of a small lion. The estimated average weight for the species ranges from 101 to 130 kg.[1]

Description

Pound for pound, Thylacoleo carnifex had the strongest bite of any mammal species living or extinct; a T. carnifex weighing 101 kg (223 lb) had a bite comparable to that of a 250-kg African lion, and research suggests that Thylacoleo could hunt and take prey much larger than itself.[2] Larger animals it may have hunted include Diprotodon spp. and giant kangaroos. Its seems improbable that Thylacoleo could achieve as high a bite force as a modern-day lion, however this may have been possible when taking into consideration the size of its brain and skull. Carnivores usually have rather large brains when compared to marsupials, which lessens the amount of bone that can be devoted to enhancing bite force. Thylacoleo however, is thought to have had substantially stronger muscle attachments and therefore a smaller brain. Canids possessed elongated skulls, while cats tend to possess foreshortened ones. The similarities between cat morphology and that of Thylacoleo indicates that while though it was a marsupial, biologically it possessed greater similarities to cats, and as a result had a higher capacity for bite strength than animals within its own phyla.[3]

It also had extremely strong fore limbs, with retractable, cat-like claws, a trait previously unseen in marsupials. Thylacoleo also possessed enormous hooded claws set on large semiopposable thumbs, which were used to capture and disembowel prey. The long muscular tail was similar to that of a kangaroo. Specialized tail bones called chevrons allowed the animal to tripod itself, and freed the front legs for slashing and grasping.[4]

Its strong forelimbs, retracting claws, and incredibly powerful jaws mean it may have been possible for Thylacoleo to climb trees and perhaps to carry carcasses to keep the kill for itself (similar to the leopard today).[5]

Due to its unique predatory morphology, scientists repeatedly claim Thylacoleo to be the most specialized mammalian carnivore of all time.[6] Thylacoleo had vertical shearing ‘carnassial’ cheek–teeth that are relatively larger than in any other mammalian carnivore.[2] Thylacoleo was clearly derived from the diprotodontian ancestry due to the pronounced development of upper and lower third pre-molars which functioned extreme carnassials with complementary reduction in the molar teeth row.[7] They also had canines but they served little purpose as they were stubby and not very sharp.[8]

Thylacoleo was 71 cm (28 in) at the shoulder and about 114 cm (45 in) long from head to tail. The species T. carnifex is the largest, and skulls indicate they averaged 101 to 130 kg (223 to 287 lb), and individuals reaching 124 to 160 kg (273 to 353 lb) were common, and the largest weight was of 128–164 kg (282–362 lb).[9] Fully grown, Thylacoleo carnifex would have been close to the same size as a jaguar.[10]

Behaviour

While considered a powerful hunter, and a fierce predator, many today would assert that due to its physiology Thylacoleo was in fact a slow runner, limiting its ability to chase prey. More recently, a couple of sources have proposed that this beast might have been arboreal (living and hunting in trees). But an analysis of its scapula suggests "walking and trotting, rather than climbing ... the pelvis similarly agrees with that of ambulators and cursors [walkers and runners]". "These bones indicate that Thylacoleo was a slow- to medium-paced runner, which is likely to mean it was an ambush predator. That fits with the stripes: camouflage of the kind you need for stalking and hiding in a largely forested habitat (like tigers) rather than chasing across open spaces (like lions).”[11] New evidence also suggests that it may have been arboreal, and was at the very least capable of climbing trees.[5]

At the site at Lancefield, many bones have been excavated and have been discovered to be a part of an estimated several hundred thousand diverse individuals. Some of those bones had strange cuts on their surfaces. Automatically, it was assumed that two explanations have occurred: marks were produced by prehistoric humans during butchering or by the teeth of Thylacoleo carnifex. Through archaeological and paleoecological findings, researchers concluded that the T. carnifex had caused all the cut marks. Because of their large size, the population had to feed on other species just as large as their own just to avoid an imbalance in their diets. They may have killed by using their front claws as either stabbing weapons or as a way to grab their prey with strangulation or suffocation.[12]

Probable habitat and diet

One major feature of Thylacoleo is its dentition. "It had no canines in the lower jaw, only small, non-functional canines in the upper jaw." One possible reason for its carnivorous diet was the lack of any grinding teeth precluded the inclusion of any plant matter. According to the place where the fossils were discovered, the Habitat may have been dry, open areas with forests and woodlands.[13]

“Kangaroos (aka macropods) belong to a large, mostly herbivorous Australasian marsupial clade termed Diprotodontia. Shared characters that unite diprotodontians include diprotodonty (where there are just two lower incisors), a special epitympanic wing of the squamosal bone in the braincase, and the presence of an extra band of fibres (termed the fasciculus aberrans) that connect the two hemispheres of the brain. The monophyly of Diprotodontia is also well supported by molecular characters,” [14] and indicates that Thylacoleo carnifex may have shared ancestry with wombats and kangaroos, which are generally believed to have been herbivores. Its shared bloodline meant that while its predecessors were herbivorous, the transfer to Australia by rafting, and the lack of adequate sustenance may have led to them evolving to becoming carnivores, which is an unprecedented occurrence. While it is now thought that T. carnifex was indeed a carnivore, its diet and behaviour have been intensely debated. In addition to an early description as a herbivore, "the species has been speculatively portrayed as a consumer of crocodile eggs, a hyaena-like scavenger, a melon specialist, a leopard-like predator that dragged prey into trees, a slow-to-medium-paced runner incapable of climbing, a terrestrial version of a cookie-cutter shark or raider of kangaroo pouches, and a bear-like super-predator".[5]

Extinction

It was believed that the extinction was due to the climate changes, but human activities as an extinction driver is still possible yet unproven. There is a growing consensus that the extinction of the megafauna was caused by progressive drying starting about 700,000 years ago (700 ka). It is revealed recently that there was a major change in glacial-interglacial cycles after ~450 ka. As for human involvement's contribution to the extinction, one argument is that the arrival of humans was coincident with the disappearance of all the extinct megafauna. It is supported by the claims that during MIS3, climatic conditions are relatively stable and no major climate change would cause the mass extinction of megafauna including Thylacoleo. Due to the lack of data, the human role in the extinction cannot be proven.[15]

Although believed to have been killed by climate change, some scientists now believe Thylacoleo to have been killed by humans destroying the ecosystem with fire in addition to hunting its prey. “They found Sporormiella spores, which grow in herbivore dung, virtually disappeared around 41,000 years ago, a time when no known climate transformation was taking place. At the same time, the incidence of fire increased, as shown by a steep rise in charcoal fragments. It appears that humans, who arrived in Australia around this time, hunted the megafauna to extinction".[16] Following the extinction of T. carnifex, no other apex mammalian predators has taken their place after their disappearance.[17]

Discoveries

"The first evidence for the existence of Thylacoleo came from some material collected in the early 1830s from the Wellington Valley region, New South Wales, by Major (later Sir) Thomas Mitchell." However, it was not confirmed to be teeth from Thylacoleo at that time and further details were not given.[18]

The existence was first described by Sir Richard Owen in 1859.[19]

In 2002, eight remarkably complete skeletons of T. carnifex were discovered in a limestone cave under Nullarbor Plain, where the animals fell through a narrow opening in the plain above. Based on the placement of their skeletons, at least some survived the fall, only to die of thirst and starvation.[20][21]

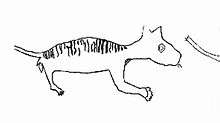

In 2008, rock art depicting what is thought to be a Thylacoleo was discovered on the north-western coast of the Kimberley. However, there is the possibility that the thylacine, a related marsupial which also had a striped coat, may be the subject of the work, instead.[22][23] The drawing represented only the second example of megafauna depicted by the indigenous inhabitants of Australia. The image contains details that would otherwise have remained only conjecture; the tail is depicted with a tufted tip, it has pointed ears rather than rounded, and the coat is striped. The prominence of the eye, a feature rarely shown in other animal images of the region, raises the possibility that the creature may have been a nocturnal hunter.[24] In 2009, a second image was found that depicts a Thylacoleo interacting with a hunter who is in the act of spearing or fending the animal off with a multiple-barbed spear. Much smaller and less detailed than the 2008 find, it may depict a thylacine, but the comparative size indicates a Thylacoleo is more likely, meaning that it is possible that Thyacoleo was extant until more recently than previously thought.[25]

In 2016, trace fossils in Tight Entrance Cave were identified as being the scratch marks of a Thylacoleo.[5]

Fossils

The first Thylacoleo fossil findings, discovered by Thomas Mitchell and described by Richard Owen, consisted of broken teeth, jaws, and skulls. It was not until 100 years later, 1966, that the first nearly-complete skeleton was found. The only pieces missing were a foot and tail. Currently, the Nullarbor Plain of West Australia remains to be the greatest finding site. These fossils now reside at the Australian Museum.[26][27]

It was reported that in 2012, an accumulation of vertebrate trace and body fossils were found in the Victorian Volcanic Plains in south-eastern Australia. It was founded that Thylacoleo was the only species that represented three divergent fossil records: skeletal, footprints, and bite marks. What this suggests is that these large carnivores had behavioral characteristics that could've increased their likelihood of their presence being detected within a fossil fauna.[28]

A characteristic seen in the remains of skull fragments is a set of carnassial teeth, suggesting the carnivorous habits of Thylacoleo. Tooth fossils of the thylacoleo exhibit specific degrees of erosion which are credited to the utility of the carnassial teeth remains as they were used for hunting and consuming prey in a prehistoric Australia teeming with other megafauna. The specialization found in the dental history of the marsupial indicates its status in the predatory hierarchy in which it existed.[29]

According to fossil records, T. carnifex is the largest known marsupial carnivore from the Australian Pleistocene. Using data collected from the most complete skeleton record available, researchers have been able to estimate the weight of the specimen to have been between 112–143 kg. In examining other specimens, it is estimated that the largest individual from the available sample weighed over 160 kg, though the estimated average weight of T. carnifex lies between 101–130 kg.[9]

Taxonomy

Family: Thylacoleonidae (Marsupial lions)

Marsupial "lion" alludes to the superficial resemblance to the placental lion and its ecological niche as a large predator. Thylacoleo is not related to the modern lion Panthera leo.

Genus: Thylacoleo (Thylacopardus) - Australia's marsupial lions, that lived from about 2 million years ago, during the late Pliocene and became extinct about 30,000 years ago, during the late Pleistocene epoch.

- Thylacoleo carnifex The holotype fossil was found in Town Cave in South Australia, in Pleistocene-aged strata. Additional possible specimens have been found at the Bow fossil site by students and staff of the University of New South Wales in 1979.

- Thylacoleo crassidentatus lived during the Pliocene, around 5 million years ago and was about the size of a large dog. Its fossils have been found in southeastern Queensland.

- Thylacoleo hilli lived during the Pliocene and was half the size of T. crassidentatus.

Fossils of other representatives of Thylacoleonidae, such as Priscileo, Microleo and Wakaleo, date back to the late Oligocene, some 24 million years.[30]

See also

References

- ↑ "The Bony Labyrinth in Diprotodontian Marsupial Mammals: Diversity in Extant and Extinct Forms and Relationships with Size and Phylogeny". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 20: 191–198. doi:10.1007/s10914-013-9228-3.

- 1 2 http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/272/1563/619.full#ref-29

- ↑ https://laelaps.wordpress.com/2007/08/31/thylacoleo-carnifex-ancient-australias-marsupial-lion/

- ↑ NOVA | Bone Diggers | Anatomy of Thylacoleo | PBS

- 1 2 3 4 Samuel D. Arman; Gavin J. Prideaux (15 February 2016). "Behaviour of the Pleistocene marsupial lion deduced from claw marks in a southwestern Australian cave". Scientific Reports #6. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ Extinct Australian "Lion" Was Big Biter, Expert Says

- ↑ Wells, Roderick T.; Murray, Peter F.; Bourne, Steven J. (2009). "Pedal morphology of the marsupial lion Thylacoleo carnifex (Diprotodontia: Thylacoleonidae) from the Pleistocene of Australia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (4): 1335–1340. doi:10.1671/039.029.0424.

- ↑ http://www.naturalworlds.org/thylacoleo/introducing/introducing_tc_1.htm

- 1 2 Wroe, S., Myers, T. J., Wells, R. T., and Gillespie, A. (1999). "Estimating the weight of the Pleistocene marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex (Thylacoleonidae : Marsupialia): implications for the ecomorphology of a marsupial super-predator and hypotheses of impoverishment of Australian marsupial carnivore faunas". Australian Journal of Zoology. 47 (5): 489–498. doi:10.1071/ZO99006.

- ↑ "Western Australian Museum".

- ↑ http://www.theguardian.com/environment/georgemonbiot/2014/apr/03/australia-marsupial-lion-kangaroos-prey/

- ↑ "Cuts on Lancefield Bones: Carnivorous Thylacoleo, Not Humans, the Cause". Archaeology in Oceania. 16: 73–80. JSTOR 40386545.

- ↑ "The Beasts of the Nullarbor | Cave". www.museum.wa.gov.au. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ↑ http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/tetrapod-zoology/vombatiform-radiation-part-i//

- ↑ "Climate change frames debate over the extinction of megafauna in Sahul (Pleistocene Australia-New Guinea)" (PDF).

- ↑ .

- ↑ Ritchie, Euan G.; Johnson, Christopher N. (2009-09-01). "Predator interactions, mesopredator release and biodiversity conservation". Ecology Letters. 12 (9): 982–998. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01347.x. ISSN 1461-0248. PMID 19614756.

- ↑ "Thylacoleo - Discovering Thylacoleo (page 1)". www.naturalworlds.org. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ↑ .

- ↑ BBC News, "Caverns give up huge fossil haul", 25 January 2007.

- ↑ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2002/08/0807_020731_TVmegafauna.html

- ↑ Flannery, T. (1990a). Australia's Vanishing Mammals. Surrey Hills, Australia: Readers Digest Press.

- ↑ Guiler, E. (1985). Thylacine: the tragedy of the Tasmanian Tiger. Melbourne, Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Akerman, Kim; Willing, Tim (March 2009). "An ancient rock painting of a marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex, from the Kimberley, Western Australia". Antiquity (journal). Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Akerman, Kim (December 2009). "Interaction between humans and megafauna depicted in Australian rock art?". Antiquity (journal). Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ http://australianmuseum.net.au/Thylacoleo-carnifex

- ↑ http://rstl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/174/575.full.pdf

- ↑ Camens, Aaron Bruce; Carey, Stephen Paul (2013-01-02). "Contemporaneous Trace and Body Fossils from a Late Pleistocene Lakebed in Victoria, Australia, Allow Assessment of Bias in the Fossil Record". PLoS ONE. 8 (1): e52957. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052957. PMC 3534647

. PMID 23301008.

. PMID 23301008. - ↑ Owen, P.. (1866). On the Fossil Mammals of Australia.--Part II. Description of an Almost Entire Skull of the Thylacoleo carnifex, Owen, from a Freshwater Deposit, Darling Downs, Queensland. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 156, 73–82. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/108939

- ↑ Long, J.A., Archer, M., Flannery, T. & Hand, S. (2002). Prehistoric Mammals of Australia and New Guinea - 100 million Years of Evolution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 224pp.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Thylacoleo carnifex |

- New study finds no evidence for theory humans wiped out megafauna

- Thylacoleo - Australia's Marsupial Lion

- Thylacoleo in Pleistocene Australia

- Steve Wroe's Web Page: Australian Megafauna

- Western Australian Museum: Thylacoleo - a voracious hunter

- PLEDGE. N 1977, A NEW SPECIES OF THYLACOLEO (MARSUPIALIA: THYLACOLEONIDAE) WITH NOTES ON THE OCCURRENCES AND DISTRIBUTION OF THYLACOLEONIDAE IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA