Spanish missions in the Americas

Part of a series on |

| Spanish missions in the Americas of the Catholic Church |

|---|

The Missionaries as They Came and Went |

| Missions |

|

|

The Spanish missions in the Americas were Catholic missions established by the Spanish Empire during the 12th to 19th centuries in an area extending from Mexico and the southwestern portions of what today are the United States, southwards as far as Argentina and Chile.

Introduction

During the Age of Discovery; the Christian Church inaugurated a major effort to spread Christianity in the New World by converting indigenous peoples. As such, the establishment of Christian missions went hand-in-hand with the colonizing efforts of European powers such as Spain, France and Portugal. For these nations, "the colonial enterprise was based on the necessity to develop European commerce and the obligation to propagate the Christian faith."[1] According to Adriaan van Oss, "Catholicism remains the principal colonial heritage of Spain in America. More than any set of economic relationships... more even than the language... the Catholic religion continues to permeate Spanish-American culture today, creating an overriding cultural unity which transcends the political and national boundaries dividing the continent."[2]

Criticism

Christian leaders and Christian doctrines have been accused of justifying and perpetrating violence against Native Americans found in the New World.[3][4] Michael Wood asserts that the indigenous peoples were not considered to be human beings and that the colonisers was shaped by "centuries of Ethnocentrism, and Christian monotheism, which espoused one truth, one time and version of reality.”[5] Jordan writes "The catastrophe of Spanish America's rape at the hands of the Conquistadors remains one of the most potent and pungent examples in the entire history of human conquest of the wanton destruction of one culture by another in the name of religion."[6]

According to Colin Calloway, the "Spanish missions also produced massive population decline, food shortages, increased demands for labor, and violence."[7]

However, other scholars point out that the Catholic Church often defended the rights of Native Americans.[8] For example, Jesuits devoted themselves to the interests of Native Americans.[9][10]

North America

Arizona

In the Spring of 1687, a Jesuit missionary named Father Eusebio Francisco Kino lived and worked with the Native Americans in the area called the Pimería Alta, or "Upper Pima Country," which presently is located in the areas between the Mexican state of Sonora and the state of Arizona in the United States. During Father Eusebio Kino's stay in the Pimería Alta, he founded over twenty missions in eight mission districts. In Arizona, unlike Mexico, missionization proceeded slowly.

Father Kino founded missions San Xavier and San Miguel at the Piman communities of Bac and Guevavi along the Santa Cruz.

Carolinas

The Spanish missions in the Carolinas were part of a series of religious outposts that Spanish Catholics established to spread Christian doctrine among the local Native Americans. The principal coastal mission and fort in the area was Santa Elena, which survived until 1587. A small mission in the interior of North Carolina called

Georgia

The Spanish missions in Georgia comprise a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholics to spread Christian doctrine among the local Native Americans. The Spanish chapter of Georgia's earliest colonial history is dominated by the lengthy mission era, extending from 1568 through 1684. Catholic missions were the primary means by which Georgia's indigenous Native American chiefdoms were assimilated into the Spanish colonial system along the northern frontier of greater Spanish Florida.

The early missions in present-day Georgia were established to serve the Guale and various Timucua peoples, including the Mocama. Later the missions served other peoples who had entered the region, including the Yamassee.

Las Californias

In the Las Californias Province of New Spain in the Americas, Catholic Franciscans established and maintained missions from 1769 to 1823 for the purpose of protecting Spain's territory by settlements and converting the Californian Native Americans to a Roman Catholicism.

The missionaries operated in cooperation with the Spanish government and military to settle present day California and protect it from Imperial Russian and British colonial advances.Junípero Serra, the Franciscan priest in charge of this effort, founded a series of missions that became economic, political, and religious institutions.[11] These missions brought grain, cattle, and a changed homeland for the California Native Americans. They had no immunity to European diseases, with subsequent indigenous tribal population falls. However, by bringing Western civilization to the area, these missions and the Spanish government have been held responsible for wiping out nearly a third of the native population, primarily through disease.[12] Overland routes were established from New Spain (Mexico) that resulted in the establishment of a mission and presidio (fort) - now San Francisco (1776), and a pueblo (town) - now Los Angeles (1781).

Clash of Cultures

The clash of Spanish and native cultures during the Spanish Las Californias-New Spain and Mexican Alta California eras of control had lasting consequences after American statehood. The Spanish occupation of California brought some negative consequences to the Native American cultures and populations, both those two missionaries were in contact with and others that were traditional trading partners. These aspects have received more research in recent decades.

The Spanish missions in Baja California comprise a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholic religious orders, the Jesuits, the Franciscans and the Dominicans, between 1683 and 1834 to spread the Christian doctrine among the local natives. The missions gave Spain a valuable toehold in the frontier land, and introduced European livestock, fruits, vegetables, and industry into the region. Eventually, a network of settlements was established wherein each of the installations was no more than a long day's ride by horse or boat (or three days on foot) from another.

As early as the voyages of Christopher Columbus, the Kingdom of Spain sought to establish missions to convert pagans to Catholicism in Nueva España (New Spain). New Spain consisted of the Caribbean, Mexico, and portions of what is now the Southwestern United States. To facilitate colonization, the Catholic Church awarded these lands to Spain.

California

The Spanish missions in California comprise a series of religious and military outposts established by Spanish Catholics of the Franciscan Order between 1769 and 1823 to spread the Christian faith among the local Native Americans. The missions represented the first major effort by Europeans to colonize the Pacific Coast region, and gave Spain a valuable toehold in the frontier land. The settlers introduced European livestock, fruits, vegetables, cattle, horses and ranching into the Californiaregion; however, the Spanish occupation of California also brought with it serious negative consequences to the Native American populations with whom the missionaries came in contact. The government of Mexico shut down the missions in the 1830s. In the end, the mission had mixed results in its objective to convert, educate, and "civilize" the indigenous population and transforming the natives into Spanish colonial citizens. Today, the missions are among the state's oldest structures and the most-visited historic monuments. Many were founded by Junipero Serra, a Franciscan friar.

Mexico

The Spanish missions in Mexico are a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholic Franciscans, Jesuits, Augustinians, and Dominicans to spread the Christian doctrine among the local natives. Since 1493, the Kingdom of Spain had maintained a number of missions throughout Nueva España (New Spain, consisting of Mexico and portions of what today are the Southwestern United States) to facilitate colonization of these lands. In 1533, at the request of Hernán Cortés, Carlos V sent the first Franciscan monks with orders to establish a series of installations throughout the country.

Sonoran Desert

The Spanish missions in the Sonoran Desert are a series of Jesuit Catholic religious outposts established by the Spanish Catholic Jesuits and other orders for religious conversions of the Pima and Tohono O'odham indigenous peoples residing in the Sonoran Desert. An added goal was giving Spain a colonial presence in their frontier territory of the Sonora y Sinaloa Province in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and relocating by Indian Reductions (Reducciones de Indios) settlements and encomiendas for agricultural, ranching, and mining labor.

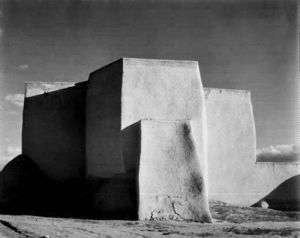

New Mexico

The Spanish missions in New Mexico were a series of religious outposts established by Franciscan friars under charter from the governments of Spain and New Spain to convert the local Pueblo, Navajo and Apache Indians to Christianity. The missions also aimed to pacify and Hispanicize the natives. The missions introduced European livestock, fruits, vegetables, and industry such as winemaking and farming into the Southwest region. Fray Marcos de Niza, sent by Coronado, first saw the area now known as New Mexico in 1539. The first permanent settlement was Mission San Gabriel, founded in 1598 by Juan de Oñate near what is now known as the San Juan Pueblo.

Texas

The Spanish Missions in Texas comprise a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholic Dominicans, Jesuits, and Franciscans to spread the Christian doctrine among the local Native Americans, but with the added benefit of giving Spain a toehold in the frontier land. The missions introduced European livestock, fruits, vegetables, and industry into the Texas region. In addition to the presidio (fort) and pueblo (town), the misión was one of the three major agencies employed by the Spanish crown to extend its borders and consolidate its colonial territories. In all, twenty-six missions were maintained for different lengths of time within the future boundaries of the state.

Since 1493, Spain had maintained a number of missions throughout New Spain (Mexico and portions of what today are the Southwestern United States) to facilitate colonization of these lands. The East Texas missions were a direct response to fear of French encroachment when the remains of La Salle's Fort Saint Louis were discovered near Matagorda Bay in 1689.

Following government policy, Franciscan missionaries sought to make life within mission communities closely resemble that of Spanish villages and Spanish culture. To become Spanish citizens and productive inhabitants, Native Americans learned vocational skills. As plows, farm implements, and gear for horses, oxen, and mules fell into disrepair, blacksmithing skills soon became indispensable. Weaving skills were needed to help clothe the inhabitants. As buildings became more elaborate, mission occupants learned masonry and carpentry under the direction of craftsmen contracted by the missionaries.

In the closely supervised setting of the mission the Native Americans were expected to mature in Christianity and Spanish political and economic practices until they would no longer require special mission status. Then their communities could be incorporated as such into ordinary colonial society. This transition from official mission status to ordinary Spanish society, when it occurred in an official manner, was called "secularization." In this official transaction, the mission's communal properties were privatized, the direction of civil life became a purely secular affair, and the direction of church life was transferred from the missionary religious orders to the Catholic diocesan church. Although colonial law specified no precise time for this transition to take effect, increasing pressure for the secularization of most missions developed in the last decades of the 18th century.

This mission system was developed in response to the often very detrimental results of leaving the Hispanic control of relations with Native Americans on the expanding frontier to overly enterprising civilians and soldiers. This had resulted too often in the abuse and even enslavement of the Indians and a heightening of antagonism.

In the end, the mission system was not politically strong enough to protect the Native Americans against the growing power of ranchers and other business interests that sought control over mission lands and the manpower represented by the Native Americans. In the first few years of the new Republic of Mexico-between 1824 and 1830-all the missions still operating in Texas were officially secularized, with the sole exception of those in the El Paso district, which were turned over to diocesan pastors only in 1852.

Trinidad

In 1687 the Catholic Catalan Capuchin friars were given responsibility for religious conversions of the indigenous Amerindian residents of Trinidad and the Guianas. In 1713 the missions were handed over to the secular clergy. Due to shortages of missionaries, although the missions were established they often went without Christian instruction for long periods of time.

Between 1687 and 1700 several missions were founded in Trinidad, but only four survived as Amerindian villages throughout the eighteenth century - La Anuncíata de Nazaret de Savana Grande (modern Princes Town), Purísima Concepción de María Santísima de Guayri (modern San Fernando), Santa Ana de Savaneta (modern Savonetta), Nuestra Señora de Montserrate (probably modern Mayo). The mission of Santa Rosa de Arima was established in 1789 when Amerindians from the former encomiendas of Tacarigua and Arauca (Arouca) were relocated further west.

South America

Chiloé Archipelago

Chiquitos

See also

References

- ↑ Gerrie ter Haar, James J. Busuttil, eds. (2005). Bridge or barrier: religion, violence, and visions for peace, Volume 2001. BRILL. p. 125.

- ↑ van Oss, Adriaan C. Catholic Colonialism: A Parish History of Guatemala, 1524-1821.

- ↑ Carroll, Vincent, Christianity on trial: arguments against anti-religious bigotry, p 87.

- ↑ Hastings, Adrian, A World History of Christianity, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000, pp 330-349

- ↑ Conquistadors, Michael Wood, p. 20, BBC Publications, 2000

- ↑ "In the Name of God : Violence and Destruction in the World's Religions", M. Jordan, 2006, p. 230.

- ↑ Calloway, Colin G. (1998). New worlds for all: Indians, Europeans, and the remaking of early America. JHU Press. p. 78.

- ↑ http://www.catholic.com/magazine/articles/the-church-and-the-native-americans

- ↑ http://academic.sun.ac.za/forlang/bergman/real/mission/h_miss.htm

- ↑ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07045a.htm

- ↑ Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History (2007), pp. 111–2

- ↑ King, Mission to Paradise (1975), p. 169

- ↑ Paddison, p. 130

- ↑ Saunders and Chase, p. 65

- ↑ Kelsey, p. 18