Siege of Castelnuovo

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

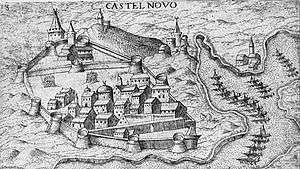

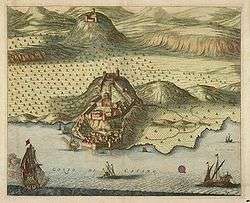

The Siege of Castelnuovo was an engagement during the Ottoman-Habsburg struggle for control of the Mediterranean, which took place in July 1539 in the walled town of Castelnuovo, present-day Herceg Novi, Montenegro. Castelnuovo had been conquered by elements of various Spanish tercios the year before during the failed campaign of the Holy League against the Ottoman Empire in Eastern Mediterranean waters. The walled town was besieged by land and sea by a powerful Ottoman army under Hayreddin Barbarossa, who offered an honorable surrender to the defenders. These terms were rejected by the Spanish commanding officer Francisco de Sarmiento and his captains even though they knew that the Holy League's fleet, defeated at the Battle of Preveza, could not relieve them.[1] During the siege the Barbarossa's army suffered heavy losses due to the stubborn resistance of Sarmiento's men. However, Castelnuovo eventually fell into Ottoman hands and almost all the Spanish defenders, including Sarmiento, were killed. The loss of the town ended the Christian attempt to regain control of the Eastern Mediterranean. The courage displayed by the Old Tercio of Naples, however, was praised and admired throughout Europe and was the subject of numerous poems and songs.[3][4]

Background

.jpg)

In 1538 the main danger to Christianity in Europe was the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. The armies of the Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent had been stopped at Vienna in 1529.[6] In the Mediterranean, a Christian offensive attempted to eliminate the danger of the great Turkish fleet in 1535, when a strong armada under Don Álvaro de Bazán and Andrea Doria captured the port of Tunis, expelling Ottoman admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa from the waters of the Western Mediterranean.[6] The Ottoman admiral was then required to return to Constantinople, where he was appointed commander of a great fleet to conduct a campaign against the Republic of Venice's possessions in the Aegean and Ionian Seas. Barbarossa captured the islands of Syros, Aegina, Ios, Paros, Tinos, Karpathos, Kasos, Naxos, and besieged Corfu.[6] The Italian cities of Otranto and Ugento and the fortress of Castro, in the province of Lecce, were also looted.[6]

The Republic of Venice, frightened by the loss of their possessions and the ruin of their trade, conducted a vigorous campaign for the creation of a "Holy League" to recover the lost territories and expel the Ottomans from the sea.[6] In February 1538, Pope Paul III succeeded in creating a league which united the Papacy itself, the Republic of Venice, the Empire of Charles V, the Archduchy of Austria and the Knights of Malta.[2] The Allied fleet for the campaign was supposed to consist of 200 galleys and another 100 auxiliary ships, and the army of about 50,000 infantry and 4,500 cavalry. But only 130 galleys and an army of around 15,000 infantry, mostly Spaniards, were all that could be gathered.[2][7] The command of the fleet was given nominally to the Genoese Andrea Doria, but Vicenzo Capello and Marco Grimaldi, commanding officers of the Papal and Venetian fleets respectively, had almost twice as many ships as Doria.[2] The commander of the army was unquestionably Hernando Gonzaga, Viceroy of Sicily.[2]

Differences among the commanders of the fleet diminished its effectiveness against an experienced opponent like Barbarossa. This was seen in the Battle of Preveza, fought in the Gulf of Arta. But the Holy League fleet provided support to the land forces that landed on the Dalmatian coast and captured the town of Castelnuovo.[8] This small town was a strategic fortress between the Venetian possessions of Cattaro and Ragusa in the area known as Venetian Albania. Venice therefore claimed ownership of the city, but Charles V refused to cede it. This was the beginning of the end of the Holy League.[8][9]

The town of Castelnuovo was garrisoned with approximately 4,000 men.[8] The main force was a tercio of Spanish veteran soldiers numbering about 3,500 men under the experienced Maestro de Campo Francisco Sarmiento de Mendoza y Manuel. This tercio, named Tercio of Castelnuovo, was formed by 15 flags (companies) belonging to other tercios, among them the Old Tercio of Lombardy, dissolved the year before after a mutiny for lack of pay.[10] The 15 captains in charge of the flags were Machín de Munguía, Álvaro de Mendoza, Pedro de Sotomayor, Juan Vizcaíno, Luis Cerón, Jaime de Masquefá, Luis de Haro, Sancho de Frías, Olivera, Silva, Cambrana, Alcocer, Cusán, Borgoñón and Lázaro de Coron.[11] The garrison also included 150 light cavalry soldiers, a small contingent of Greek soldiers and knights under Ándres Escrápula, and some artillery pieces managed by 15 gunners under captain Juan de Urrés.[11] The chaplain of Andrea Doria, named Jeremías, also remained in Castelnuovo along with 40 clerics and traders and was appointed bishop of the town.[11]

The reason for the garrison's large size was that Castelnuovo was projected to be the beachhead for a great offensive against the heart of the Ottoman Empire.[8][12] However, the fate of the troops who were in the fortress depended entirely on the support of the fleet, and this had been defeated by Barbarossa at Preveza before the capture of Castelnuovo. Moreover, in a short time Venice withdrew from the Holy League after accepting a disadvantageous agreement with the Ottomans.[13][14] Without Venetian ships, the Allied fleet had no chance to defeat the Ottoman fleet commanded by Barbarossa, who was by this time supported by another experienced officer, Turgut Reis.[14]

Siege

First maneuvers

Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent ordered Barbarossa to reorganize and rearm his fleet during the winter months to have it ready for the battle in the spring of 1539. 10,000 infantry soldiers and 4,000 Janissaries were embarked aboard the warships to reinforce the troops of the galleys.[14] According to the orders received, Barbarossa's army, numbering about 200 ships with 20,000 fighting men aboard, would blockade Castelnuevo by sea while the forces of the Ottoman governor of Bosnia, a Persian named Ulamen, would besiege the fortress by land in command of 30,000 soldiers.[14] Sarmiento, meanwhile, used the peaceful months prior to the siege to improve the defenses of the town, repairing walls and bastions and building new fortifications. In the event he could not do much due to a lack of available means, as there was no plan to fortify the town since it was supposed to function as a beachhead.[14] Captain Alcocer was sent to Spain with instructions to call for help; Pedro de Sotomayor was sent to Sicily and Captain Zambrana to Brindisi, all in vain.[15] Andrea Doria, who was in Otranto with 47 Imperial and 4 Maltese galleys, received news of Castelnuovo's situation, but given the inferiority of his fleet he sent a message to Sarmiento recommending him to surrender.[16]

In June Barbarossa sent 30 galleys to block the entrance of the Gulf of Cattaro.[15] The vessels reached Castelnuovo on 12 June and disembarked a thousand soldiers with the aim of finding water and capturing Spanish soldiers or local civilians to gain information.[15] Once the Spanish were warned of their enemy's presence, Sarmiento dispatched three companies under Captain Machín de Munguía and the cavalry under Lázaro de Corón to attack them before lunchtime.[15] After a fierce fight the Ottoman landing party was forced to re-embark, although it returned in the afternoon. Then it was beaten by Francisco de Sarmiento in person, who was waiting for a new attempt together with Captains Álvaro de Mendoza, Olivera and Juan Vizcaíno, and 600 soldiers. Three hundred Ottomans were killed during the battle, and another 30 captured.[17] The remainder escaped to their ships.[17]

On 18 July Barbarossa arrived with the main force and immediately began to land troops and artillery while waiting for the arrival of Ulamen, who came along with his army a few days later.[18] The Ottoman pioneers spent five days digging trenches and building ramparts for 44 heavy siege guns carried aboard Barbarossa's fleet or by Ulamen's troops, and even smoothed the fields around Castelnuovo to facilitate maneuvers.[18] Castelnuovo was also bombarded by sea, as ten pieces had been previously embarked aboard the galleys.[18] The Spanish, meanwhile, undertook several sorties to obstruct the siege works. These raids inflicted many casualties, among them Agi, one of Barbarossa's favorite captains.[18] Another sortie by a Spanish force of 800 men surprised several units of Janissaries who were attempting to storm the walls of Castlenuovo, killing most of them and leaving the field strewn with corpses. When Barbarossa was informed about the setback, he severely reprimanded his officers, as the losses of the Ottoman elite corps were difficult to replace. He gave orders forbidding skirmishes to avoid a repeat of the defeat.[17]

Great assault

By 23 July, Barbarossa's army was ready to begin a general assault and his artillery prepared to break down the walls of Castelnuovo. Enjoying a vast numerical superiority over the Spanish garrison, which was completely isolated and unable to receive support or supplies, Barbarossa offered an honorable surrender to the Spanish.[15] Sarmiento and his men would be granted a safe passage to Italy, the soldiers retaining their weapons and flags. Barbarossa added to his offer the incentive of giving each soldier 20 ducats.[15] His only demand to Sarmiento was the abandonment of his artillery and gunpowder. Two squad corporals of Captain Vizcaino's company, Juan Alcaraz and Francisco de Tapia, managed to return to Naples and write their version of events many years later.[15] They recorded the answer given to Barbarossa that "the Maestro de Campo consulted with all the captains, and the captains with his officers, and they decided that they preferred to die in service of God and His Majesty."[15]

The great assault on the city was launched shortly after, and lasted all day.[19] It was costly in lives, as the Ottomans employed both infantry and artillery at the same time to assault and bombard Castelnuovo, resulting in heavy casualties among the Ottomans themselves due to both friendly fire and Spanish defending.[19] During the night the Spanish improved their defenses and plugged the gaps opened in the walls. When the attack was resumed the next morning, Saint James Day, Bishop Jeremías remained with the soldiers, encouraging them and confessing those who were mortally wounded along the attacked perimeter. About 6,000 Ottoman soldiers were killed in the bloody assault, while the Spanish suffered only 50 killed; although the number of men who died from their wounds was probably large.[11]

Encouraged by the successful defense, several Spanish soldiers decided to conduct a surprise raid on the Ottoman camp with the approval of Sarmiento.[20] Thus, one morning, 600 men took the unprepared besiegers by surprise. In some places the assault could not be stopped, and panic spread among the Ottomans. Many troops broke and ran, including some Janissaries who fled throughout their own camp breaking down the tents, including that of Barbarossa.[20] The Admiral's personal guard feared for the safety of its lord, and, ignoring his protests, took him to the galleys along with the standard of the Sultan.[20]

During the following days most of the artillery concentrated its fire on a fort in the upper town. Barbarossa thought that it was the key point of Castelnuovo's fortifications and proposed to capture it.[20] The remaining cannons, meantime, continued firing at the fragile walls of the town. On 4 August, Barbarossa ordered an assault against the ruins of the fort, which was now completely shattered, with its casemates ruined. As a major point of the defense, Sarmiento had reinforced the garrison and removed the wounded in the preceding days. The assault began at dawn and the battle lasted all day. Captain Machín of Munguía distinguished himself in the fight, leading the defenders with great courage.[20] By nightfall the remnants of the Spanish garrison retreated to the walls of the town with their wounded, leaving the ruined castle in Barbarossa's hands. The day was very costly in lives. Of the Spanish officers defending the castle only Captains Masquefá, Munguía, Haro, and a corporal surnamed Galaz survived.[20] The remainder had been killed in the battle. Among the very few survivors that the Ottomans captured, they found three deserters. These were immediately brought to Barbarossa and encouraged the admiral to continue with the assaults, reporting that the Spanish had suffered heavy casualties, lacked gunpowder and shot, and were mostly injured and exhausted.[20]

Ottoman capture

On 5 August a new attack was launched against the walls. Barbarossa, after the report of the Spanish deserters, was sure that he could soon capture Castelnuevo. All the Janissaries took part in the action, and the cavalry was ordered to dismount to join the general assault.[21] Despite the overwhelming numerical superiority of the Ottoman troops, the Spanish defense was successful, as no more than a tower of the wall fell to the besiegers that day.[21] Sarmiento ordered his sappers to prepare a mine to destroy the tower, but the attempt failed when an unexpected burst of the gunpowder killed the soldiers who were working in the mine.[21] At dawn on the following day a heavy downpour ruined the matchlocks of the harquebuses, the few remaining pieces of artillery, and the last gunpowder. The fight was therefore sustained only with swords, pikes and knives, and the wounded Spanish soldiers were forced to take up arms and help defend the walls.[21] Only the dying men remained in the hospital. Surprisingly, the few surviving Spanish managed to repel the assault.[22]

The last and definitive attack took place the next morning. Francisco de Sarmiento, on horseback, was wounded in the face by three arrows, but he continued to encourage his men.[23] Demolished by heavy gunfire, the ruins of the walls became indefensible. Sarmiento then ordered the 600 Spanish survivors to retreat. His idea consisted of defending a castle in the lower city where the civilian population of Castelnuovo had taken refuge.[23] Although the withdrawal was made in perfect order and discipline, Sarmiento and his men found that the doors of the castle were walled at their arrival.[23] Sarmiento was offered a rope to raise him to the walls,[23] but refused and responded "Never God wants that I was saved and my companions were lost without me".[5][23] After that he joined Machín de Munguía, Juan Vizcaíno and Sancho Frias to lead the last stand. Surrounded by the Ottoman army, the last Spanish soldiers fought back to back until none were able to fight. At the end of day, Castelnuovo was in Ottoman hands.[24]

Aftermath

Almost all of the Janissaries and 16,000 from the other Ottoman units were killed in the assault. According to rumor, Turkish losses amounted to 37,000 dead.[4][5] Of the Spanish troops only 200 survived, most of them wounded. One of the prisoners was the Biscayan Captain Machín de Munguía. Barbarossa, upon learning this, offered Munguía freedom and a place in his army. The admiral greatly admired him for his actions in the battle of Preveza, where the Spaniard had successfully defended a sinking Venetian carrack against several Ottoman warships.[25] Munguía refused to accept and was therefore beheaded on the spur of the admiral's galley.[4] Half of the prisoners and all the clerics were also slaughtered to satisfy the Ottoman soldiers, who were angry at the great losses which they had suffered in capturing the city.[4] The few survivors were taken as slaves to Constantinople. Twenty-five of them managed to escape from prison six years later and sailed to the port of Messina.[4]

Despite the failure of Sarmiento to retain the fortress, Castelnuovo's defense was sung by numerous contemporaneous poets and praised all over Christian Europe.[4] The Spanish soldiers who participated in the unequal engagement were compared with mythological and classical history heroes, being considered immortal due the magnitude of their feat.[4] Only the enemies of Charles V, such as the Paduan humanist Sperone Speroni, rejoiced at the annihilation of the Tercio of Castelnuovo.[26]

The siege of Castelnuovo ended the failed campaign of the Holy League against the power of the Ottoman Empire in the Eastern Mediterranean. Charles V began negotiations with Barbarossa to attract him to the imperial ranks but in vain, and turned all his efforts in a great expedition against Algiers to destroy the Ottoman sea power.[27] This expedition, known as the Journey of Algiers, ended in a disaster as a storm scattered the fleet and the army had to be reembarked having suffered heavy losses.[28] A truce between Charles V and Suleiman the Magnificent was signed in 1543. Castelnuovo remained in Ottoman hands for almost 150 years. It was recaptured in 1687, during the Morean War, by the Venetian Captain-General at sea Girolamo Cornaro, who in alliance with Montenegrins under Vuceta Bogdanovic, won a victory over the Turks near the town and put the fortress under Venetian rule.[29]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 Fernández Álvarez, p. 229

- 1 2 3 4 5 Arsenal/Prado, p. 23

- 1 2 3 Martínez Laínez, p. 116

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Arsenal/Prado, p. 33

- 1 2 3 De Sandoval, p. 377

- 1 2 3 4 5 Arsenal/Prado, p. 22

- ↑ Fernández Duro, p. 234

- 1 2 3 4 Arsenal/Prado, p. 24

- ↑ Fernández Duro, p. 269

- ↑ 6 flags of the Tercio of Florence, 3 of the Tercio of Lombardy, 2 of the Tercio of Naples, one of the Tercio of Nice and three new flags. Fernández Álvarez, Carlos V, el César y el hombre, p. 579

- 1 2 3 4 De Sandoval, p. 375

- ↑ Fernández Duro, p. 228

- ↑ Levin, p. 159

- 1 2 3 4 5 Arsenal/Prado, p. 25

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Arsenal/Prado, p. 27

- ↑ Fernández Duro, p. 247

- 1 2 3 De Sandoval, p. 374

- 1 2 3 4 Arsenal/Prado, p. 26

- 1 2 Arsenal/Prado, p. 28

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Arsenal/Prado, p. 29

- 1 2 3 4 Arsenal/Prado, p. 30

- ↑ Arsenal/Prado, p. 31

- 1 2 3 4 5 Arsenal/Prado, p. 32

- ↑ Arsenal/Prado, p. 34

- ↑ Fernández Duro, p. 244

- ↑ Croce, p. 317

- ↑ Martínez Ruiz/Giménez, pp. 145-146

- ↑ Martínez Ruiz/Giménez, p. 146

- ↑ Jaques, p. 210

References

- Arsenal, León; Prado, Fernando (2008). Rincones de historia española (in Spanish). EDAF. ISBN 978-84-414-2050-2.

- Croce, Benedetto (2007). España en la vida italiana del Renacimiento (in Spanish). Editorial Renacimiento. ISBN 978-84-8472-268-7.

- Fernández Álvarez, Manuel (2001). El Imperio de Carlos V (in Spanish). Taravilla: Real Academia de la Historia. ISBN 978-84-89512-90-0.

- Fernández Álvarez, Manuel (1999). Carlos V, el César y el hombre (in Spanish). Espasa-Calpe. ISBN 84-239-9752-9.

- Fernández Duro, Cesáreo (1895). Armada Española desde la unión de los reinos de Castilla y Aragón (in Spanish). I. Madrid, Spain: Est. tipográfico "Sucesores de Rivadeneyra".

- Jacob Levin, Michael (2005). Agents of empire: Spanish ambassadors in sixteenth-century Italy. New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4352-7.

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity Through the Twenty-first Century. 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33538-9.

- Martínez Laínez, Fernando; Sánchez de Toca Catalá; José María (2006). Tercios de España: la infantería legendaria (in Spanish). Madrid: EDAF. ISBN 978-84-414-1847-9.

- Martínez Ruiz, Enrique; Giménez, Enrique (1994). Introducción a la historia moderna (in Spanish). Ediciones AKAL. ISBN 978-84-7090-293-2.

- De Sandoval, Prudencio (1634). Historia de la vida y hechos del emperador Carlos V (in Spanish). Bartolomé París (Pamplona), Pedro Escuer (Zaragoza).

Coordinates: 42°27′10″N 18°31′52″E / 42.45278°N 18.53111°E