Postage stamps and postal history of Palestine

The postage stamps and postal history of Palestine emerges from its geographic location as a crossroads amidst the empires of the ancient Near East, the Levant and the Middle East. Postal services in the region were first established in the Bronze Age, during the rule of Sargon of Akkad, and successive empires have established and operated a number of different postal systems over the millennia.

In the era of modern postage, the postal administrations in Palestine have included Austrian, French, Italian, German, Egyptian, and Russian post offices (through arrangements made with the Ottoman Empire), the Egyptian Expeditionary Forces, the British Mandate, and various interim authorities in the lead up to and after the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Since 1948, postal services have been provided by Egypt, Jordan, Israel, and the Palestinian National Authority.

When discussing the pre-1948 postal history, most philatelists refer to this geographic area as Palestine or the Holy Land, though some also use Eretz Israel. This article surveys the postal history leading up to the area's two current postal administrations, that of the State of Israel and the Palestinian National Authority.

Background

Classic antiquity

Prior to modern postal history, imperial administrations set up mechanisms for the delivery of packages and letters.

The earliest use of a postal system in the region is thought to date back to the Bronze Age, during the rule of Sargon of Akkad (2333–2279 BCE). His empire, "was bound together by roads, along which there was a regular postal service, and clay seals which took the place of stamps are now in the Louvre bearing the names of Sargon and his son."[1]

During Persian rule (538–333 BCE), an extensive network of roads maintained by the Persian government formed part of an efficient imperial postal system. The postal system's establishment and the improvements to the road network are credited to the monarch Darius I (521–486 BCE).[2] Mounted couriers, known as "fast messengers" (Persian language:pirradaziš), carried correspondence between the royal court and the provinces, stopping only to eat and rest, and change horses as needed, at supply stations located about one day's travel apart.[3] The Persian courier system forms part of the backdrop to events described in the Hebrew Bible's Book of Esther.[4]

Arab Caliphates (628–1099)

The Umayyad empire (661–750) who introduced the "first purely Arab coinage" in Palestine also developed a system of postal service.[5] Khans distributed along the main north-south and east-west roads that served as resting places for pilgrims and travellers facilitated the operation of the postal service, known as the barid.[6] A postal system known as the Barīd (Arabic: بريد) was also operated under the rule of the Abbasid caliphate (750–969), and the word is still used today for "mail" throughout the Arab world.[7][8] Under Fatimid rule (969–1099), a pigeon post was maintained that was later perfected by the Mamluks. The pedigrees of carrier pigeons were kept in a special registrar.[9]

Crusader period (1099–1187)

The chroniclers of the First Crusade documented the chance interception of a message warning the duke of Caesarea of the coming of the Crusader armies when a carrier pigeon was felled by a hawk over a Crusader military encampment in May 1099. The message, written in Arabic, read as follows:

Greetings from the king of Acre to the duke of Caesarea. A generation of dogs, a foolish, headstrong, disorderly race, has gone through my land. If you value your way of life, you and others of the faith should bring harm to them, since you can easily do what you wish. Transmit this message to other cities and strongholds.[10]

Carrier pigeons were regularly used in this period. For example, Edward Gibbon notes that during the siege of Acre (1189–1191) by the Crusaders, the inhabitants of the besieged city kept a regular correspondence with the Sultan's forces by way of carrier pigeon.[11]

Mamluk rule (1270–1516)

During the rule of the Mamluks, mounted mail service was operated in Deir el-Balah, Lydda, Lajjun and other towns on the Cairo to Damascus route.[12] The postal system established by the Mamluks, under the leadership of Baybars, was known as the Barīd, as it was during the period of Arab caliphate rule. The nephew of the chief secretary to Sultan Baybars attributed the Barid's adoption and development by the Mamluks to the recommendations of his uncle, al-Sahib Sharaf al-Din Abu Muhammed Al-Wahab. The nephew records that in response to a request from Baybars to be kept up-to-date on the most recent developments concerning the Franks and the Mongols, Al-Wahab, "explained to him that which the Barīd had achieved in ancient and caliphal times and proposed [this system] to him; [the sultan] liked the idea and ordered [its establishment]."[8]

After the Mamluks dislodged the Crusaders, annexed the Ayyubid principalities, and defeated the Mongol army in Anatolia, Baybars established the province of Syria (which included Palestine), with Damascus as its capital. At this point, imperial communications throughout Palestine were so efficient that Baybars would boast that he could play polo in Cairo and Damascus in the same week. An even more rapid carrier pigeon post was maintained between the two cities.[13] Its use in forming a defensive league against the Crusaders was noted by Raymond of Agiles, who thought it rather "unsporting".[14]

Ottoman rule (1516–1918)

Postal services in the Ottoman empire

During Ottoman rule in Palestine, stamps issued by the Ottoman authorities were valid in Palestine.[15] In 1834, after improving its transport and communication systems, the Ottomans established a new imperial postal system. Ottoman post offices operated in almost every large city in Palestine, including Acre, Haifa, Safed, Tiberias, Nablus, Jerusalem, Jaffa, and Gaza.[16] Thanks to the work of philatelic scholars, it is possible to reconstruct a reliable list of Ottoman post offices in Palestine.

The Imperial edict of 12 Ramasan 1256 (14 October 1840)[17] led to substantial improvements in the Ottoman postal system and a web of prescribed and regular despatch rider (tatar) routes was instituted.[18] Beginning in 1841, the Beirut-route was extended to serve Palestine, going from Beirut via Damascus and Acre to Jerusalem.[19]

Postal services were organized at the local level by the provincial governors and these leases (posta mültesimi) came up for auction annually in the month of March.[18] It is reported that in 1846 Italian businessmen Santelli and Micciarelli became leaseholders and ran a service from Jerusalem to Ramle, Jaffa, Sûr, and Saida.[20] By 1852, a weekly service operated from Saida via Sûr, Acre (connection to Beirut), Haifa, and Jaffa to Jerusalem, also serving Nablus beginning in 1856. That same year, two new routes came into operation: Jerusalem–Hebron–Gaza, and Tiberias–Nazareth–Shefa-'Amr–Acre.[21] In 1867, the Jerusalem—Jaffa route operated twice a week, and beginning in 1884, the Nablus—Jaffa route received daily despatches.[21]

In the last century of Ottoman rule, in addition to the Ottoman state postal service, up to six foreign powers were also allowed to operate postal services on Ottoman territory, with such rights originating in the Ottoman capitulations and other bilateral treaties.[22] At the beginning of the First World War, the specific postal rights enjoyed by these foreign powers throughout the empire were revoked by the Ottoman authorities. Beginning in 1900 through until the war's end, Ottoman citizens, including those in Palestine, were forbidden to use the services of the foreign post offices.[22][23]

In A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine (1858), Josias Leslie Porter describes the system operated by the Ottoman authorities at the time:

"The Post Office in Syria is yet in its infancy. There are weekly mails between Jerusalem and Beyrout, performing the distance in about four days; there is a bi-weekly post between Damascus and Beyrout, taking about 22 hours in fine weather, but occasionally a fortnight in winter; and there is a weekly Tartar[24] from Damascus to Hums, Hamâh, Aleppo and Constantinople—making the whole distance in 12 days. He leaves on Wednesday. All letters by these routes must be addressed in Arabic or Turkish, and prepaid. The Turkish posts have no connection with those of any other country; and consequently letters for foreign countries must be sent either through the consuls, or the post agents of those countries, resident at the seaports."[25]

Ottoman post offices

Initially all the postal facilities had the status of relay stations, and letters received their postmarks only at the Beirut post office, with one exception: markings Djebel Lubnan[26] are believed to have been applied at the relay station Staura (Lebanon). In the 1860s, most relay stations were promoted to the status of branch post offices and received postmarks, initially only negative seals, of their own.[27] The postmarks of an office's postal section usually contained the words posta shubesi, as opposed to telegraf hanei for the telegraph section. In 1860, ten postal facilities operated in Palestine, rising to 20 in 1900 and 32 in 1917. Travelling post offices existed on three routes: Jaffa–Jerusalem,[23] Damascus–Haifa,[28] and Messudshi—Nablus.[29][30] No TPO postmarks are known for other railway lines.[28]

Ottoman postal rates (1840–1918)

The Imperial edict of 12 Ramasan 1256[17] and later ordinances made the distinction between three types of mail items: ordinary letters, registered letters (markings te'ahudd olunmoshdur), and official letters (markings tahirat-i mühümme).[31] Fees were calculated by the type of mail, the weight, and the distance (measured in hours): in 1840, an ordinary letter, weighing less than 10g, had a cost per hour of 1 para.[32][33] Special fees applied to samples, insured mail, special delivery, and printed matters, etc.[32] These postal rates changed frequently, and new services were added over the years. Upon joining the Universal Postal Union on 1 July 1875, Ottoman overseas rates conformed to UPU rules.

Foreign post offices

Austria and France obtained permits to provide postal service in the main cities of the Ottoman Empire as early as 1837. In 1852, the two countries opened foreign post offices in Palestine's main cities. Other European countries followed suit: Russia in 1856, Germany in 1898, and Italy in 1908. These foreign post offices facilitated family and social contacts and transfers of money from Europe to the Holy Land.[16]

Russian post offices

In the early 19th century, the Russians established shipping routes in the Eastern Mediterranean and provided a mail service. Russian postal service in the Ottoman Empire began in 1856 operated by the Russian Company of Trade and Navigation (Russkoe Obschchestvo Parokhodstva i Torgovli or ROPiT). ROPiT handled mail service between the various offices, and forwarded mail to Russia through Odessa and their offices received a status equivalent to regular Russian post offices in 1863. ROPiT shipping and postal agencies existed in Akko (1868–1873), Haifa (1859–1860, 1906–1914), Jaffa (1857–1914) and Jerusalem (1901–1914).[34][35]

Austrian post offices

The Austrian Empire established a mail system in the Mediterranean through the shipping company Österreichischer Lloyd. Lloyd postal agencies operated in Jaffa (1854), Haifa (1854), and Jerusalem (1852).[36][37] These three offices later became the Austrian Imperial and Royal Post Offices: Jerusalem (March 1859), Jaffa and Haifa (1 February 1858).[38] Collecting or forwarding agencies existed in Mea Shearim (Jerusalem), Safed, and Tiberias.[39][40] Safed and Tiberias were only served by a private courrier arranged via the local Austrian consular agent.[41] Nazareth and Bethlehem were never served by the Austrians, such cachets found on postal material and their transport to Jerusalem was arranged purely privately.[42]

In a number of Jewish settlements, local traders or officials served as auxiliary collection and deposit agents: Gedera, Hadera, Kastinie (Ber Tuviya), Petah Tiqva, Rehovot, Rishon Le Zion, Yavne'el, and Zichron Yaacov.[40][43][44] By special arrangement, as an inducement to use the Austrian service for foreign mail as well, the Austrian post transported letters and cards between these Jewish settlements free of charge.[45] The use of local or JNF labels on such postal matter was totally without any need and is known on philatelic items only.[46]

The stamps used were Austrian stamps for Lombardy-Venetia and, after 1867, Austrian Levant stamps, as pictured here.[47]

French post offices

The French operated a number of post offices in the Ottoman Empire, often in conjunction with the local French consulates. In Palestine, three offices were opened: Jaffa (1852), Jerusalem (1890) and Haifa (1906).[48][49] The stamps used were regular French ones, after 1885 stamps overprinted in Turkish currency, and from 1902 also French Levant stamps.[49] Of the French postal arrangement, Porter describes it as "quick and safe, though frequently altered."[25] French mail-steamers, known as the Messagerie Imperiale ("Postal Line"),[50] operated by the Compagnie des Services Maritimes des Messageries Nationales,[51] departed every fortnight from the coast of Syria to Alexandria and Constantinople. From the ports at Alexandretta, Latikia, Tripoli, Beirut, and Yâfa, letters could be posted to Italy, France, England or America.[25]

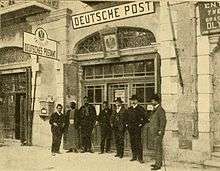

German post offices

The German Empire opened its first office on October 1, 1898, in Jaffa, followed on March 1, 1900, by an office in Jerusalem.[52][53] Both offices closed in September 1914. Auxiliary collecting agencies existed in Ramleh (1902), Rishon LeTzion (1905), Wilhelma Hamidije (1905), Sarona (1910), Emmaus (1909), Sebil Abu Nebbut (1902, a quarantine station at the Jaffa city boundary), and Jerusalem's Jaffa Gate.[54] Mail collecting points were also present in Beit Jala, Bethlehem, Hebron, and Ramallah.[55] Regular German stamps, and stamps overprinted in Turkish currency,[56] and French currency[57] were in use.[58] Stamps were only cancelled at the three post offices, mail from the agencies received boxed cachets.[59]

Italian post offices

The Italian post office in Jerusalem opened on June 1, 1908. Temporarily closed between October 1, 1911, and November 30, 1912, it operated until September 30, 1914.[60][61] The stamps used were regular (unoverprinted) Italian ones, stamps overprinted in Turkish currency, and stamps overprinted Gerusalemme.[62][63][64]

Egyptian post offices

An Egyptian post office operated in Jaffa between July 1870 and February 1872.[65] The postmark reads V.R. Poste Egiziane Iaffa.[66] An interpostals seal for Jaffa also exists.[67][68][69]

Other postal services

English travellers in the region could receive mail from abroad if addressed to the care of the English consuls in Beirut, Aleppo, Jerusalem or Damascus, or alternatively to the care of a merchant or banker.[25]

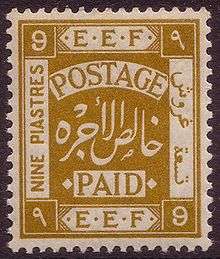

British E.E.F. stamps and service (1917–1920)

In November 1917, the British Egyptian Expeditionary Force occupied Palestine.[70][71] Initially, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (and the Indian Expeditionary Force) had given civilians basic postal services for free, with additional services paid in British or Indian stamps.[70] Free mail was withdrawn with the printing of appropriate stamps.[72][73] Two stamps inscribed E.E.F. (1 Piastre, and 5 Millièmes) were issued in February 1918,[74][75] the first definitives (11 values) were circulated from June 1918.[76][77] These E.E.F. stamps were valid in Palestine, Cilicia,[78] Syria, Lebanon, and Transjordan.[79] Prior to the British Mandate in Palestine, Hebrew was not an official language, and so these stamps bore only Arabic inscriptions besides English.[80]

British Mandate (1920–1948)

In 1920, Transjordan was separated and distinctive overprints for the two territories came into use.[81][82] As Palestine came under the civil administration of the British Mandate of Palestine[i],[81] falling into line with League of Nations rules, the High Commissioner sanctioned stamps (as pictured here) and coins bearing the three official languages of British Mandate Palestine: English, Arab, and Hebrew.[83] Between 1920 and 1923 six such distinctive overprints were issued: four produced in Jerusalem, two in London.

Local Jews and Arabs lobbied the British about the overprint (pictured):[84]

The Jewish members of the [Advisory] Council objected to the Hebrew transliteration of the word "Palestine", on the ground that the traditional name was "Eretz Yisrael", but the Arab members would not agree to this designation, which, in their view, had political significance. The High Commissioner therefore decided, as a compromise, that the Hebrew transliteration should be used, followed always by the two initial letters of "Eretz Yisrael", Aleph Yod, and this combination was always used on the coinage and stamps of Palestine and in all references in official documents.

During the Mandate, postal services were provided by British authorities. The British Post service designed its first four stamps in 1923, upon the suggestion of the Sir Herbert Samuel (the High Commissioner), following a public invitation for designs.[85] The first values in this series of definitive stamps were issued on June 1, 1927.[86] The stamps pictured the Rachel's Tomb, the Tower of David, the Dome of the Rock, and a view of a mosque in Tiberias and the Sea of Galilee. According to Reid, the British Mandate "scenes carefully balanced sites of significance to Muslims, Jews, and Christians."[87]

The postal service operated by the Mandatory authorities was reputed to be the best in the Middle East. Letters were delivered daily in Jerusalem. Palestine joined the Universal Postal Union in October 1923.[88] The post was transported by boat, train, cars and horses, and after 1927, also by air.[89] Sale and exchange of International Reply Coupons started in 1926[90] and were joined by Imperial Reply Coupons from January 1, 1935.[91] Air letter sheets (or air letter cards as they were then known) were first introduced in Palestine in November 1944.[92][93] During the volatility of 1947 and 1948, British postal services deteriorated and were replaced by ad hoc interim services prior to the partition and the establishment of the State of Israel. Just before the formal end to the British Mandate over Palestine, the Mandatory government destroyed the existing stocks of postage stamps and had Palestine removed from the World Postal Union.[94] A total of 104 stamps bearing the name "Palestine" were issued by the British between 1918 and 1942.[15]

Mandate post offices

During the British Mandate over Palestine about 160 post offices, rural agencies, travelling post offices, and town agencies operated, some only for a few months, others for the entire length of the period. Upon the advance of allied forces in 1917 and 1918, initially Field Post Offices and Army Post Offices served the local civilian population. Some of the latter offices were converted to Stationary Army Post Offices and became civilian post offices upon establishment of the civilian administration. In 1919 fifteen offices existed, rising to about 100 by 1939, and about 150 by the end of the Mandate in May 1948. With most of the Jerusalem General Post Office archives destroyed, research depends heavily on philatelists recording distinct postmarks and dates of their use.

Mandate postal rates

After occupation by allied forces in 1917, basic postage was free for civilians. Registration fees and parcels had to be franked using British or Indian stamps. Once the EEF stamps printed in Cairo came on sale, mail to overseas destinations had to be paid for from 10 February 1918, and from 16 February 1918 also mail to the then occupied territories and Egypt.

The structure of postal rates followed broadly British practice and new services, like airmail and express delivery, were added over the years. From 1926 reduced rates applied for mail to Britain and Ireland, and from 1 March 1938 to 4 September 1939, Palestine was part of the All Up Empire airmail rates system.

Transitional and local postal services (1948)

In early 1948, as the British government withdrew, the area underwent a violent transition, affecting all public services. Mail service was reportedly chaotic and unreliable. Nearly all British postal operations shut down during April. Rural services ended on April 15 and other post offices ceased operations by the end of April 1948, except for the main post offices in Haifa, Jaffa, Jerusalem, and Tel Aviv, Jaffa, and Jerusalem, which persevered until May 5.[95][96]

In Jerusalem, the French consulate is claimed to have issued stamps in May 1948 for its staff and local French nationals. The French stamps supposedly went through three issues: the first and second were "Affaires Étrangères" stamps, inscribed gratis but overprinted, while the third were "Marianne" stamps (6 francs) that arrived from France by the end of May. The consulate also created its own cancellation: Jerusalem Postes Françaises.[97] Philatelic research has exposed the French Consular post as a fraud perpetrated by the son of the then consul,[98] though other philatelists have maintained their claims that the postal service and its stamps are genuine.[99]

Minhelet Ha'am

In early May 1948, the Jewish provisional government, known as Minhelet Ha'am, did not have its own postage stamps ready, so it used existing labels,[100] both JNF labels, which otherwise have been printed since 1902 for fundraising purposes,[101] and local community tax stamps. The JNF labels were given a Hebrew overprint meaning postage (doar),[102] (as shown in the picture), whereas local community tax stamps were not given overprints.[103] The JNF stamps were printed from May 3 to 14, 1948, their sale ended on May 14, 1948, with remaining stocks ordered to be returned and destroyed.[104] Use of these stamps was tolerated until May 22, 1948.[104] The Mandate's postal rates remained unchanged during this period.[105]

Since Jerusalem was under siege, its residents continued to use JNF stamps until June 20, 1948, whereupon Israeli stamps reached the city. These stamps, overprinted with a JNF seal, bore a map of the UN Partition Plan.[106]

Minhelet Ha'am used 31 different JNF labels. Owing to different denomination and overprints, there are at least 104 variants catalogued. Eight of the stamps feature Jewish Special operations paratroopers killed during WWII, including Abba Berdichev, Hannah Szenes, and Haviva Reik, Enzo Sereni. The JNF also honored kibbutzim Hanita and Tirat Zvi, the Jewish Brigade, the Technion, the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, an illegal immigrant ship, and Zionists Yehoshua Hankin, Chaim Weizmann, Eliezer Ben Yehuda, and, pictured here, Theodore Herzl with Chaim Nachman Bialik.[107]

Local postal services

In the town of Safed, the departure in April of the British left the Haganah trying to establish control. The Haganah enlisted a postal clerk to print up postal envelopes, which were never used, as well as 2,200 stamps (10 mils each). On the stamps was written, in Hebrew: Safed mail Eretz Israel. Once stamped, mail was routed by the Haganah through Rosh Pina. These Safed emergency stamps were the only ones issued by the Haganah.[108][109] The "Doar Ivri" stamps issued by Minhelet Ha'am went on sale in Safed on May 16, 1948.[110]

In rural Rishon Lezion, the local council voted to issue their own stamps and provide a mail service via armored car. The stamps were first sold on April 4, 1948, more than a month before the establishment of the state of Israel, and service discontinued on May 6.[111] These stamps were not authorized by Minhelet Ha'am.[112]

During the 1948 War the city of Nahariya was cut off and the town administration, without authorization from Minhelet Ha'am,[112] issued local stamps.

Post-1948

Since 1948, the postal administrations for the region have been Egypt, Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian National Authority.

Egypt and Jordan

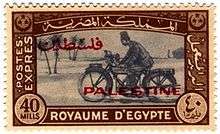

Egypt and Jordan provided the postal stamps for Gaza and the West Bank (incl. East Jerusalem) between 1948 and 1967. Both countries overprinted their own stamps with the word "Palestine".[15] Of these "Palestine" stamps, 44 issued by Jordan and 180 issued by Egypt are listed in the Scott catalogues. On occasion, the Arab Higher Committee and other entities have issued propaganda labels.

By May 5, 1948, Egypt set up postal services and issued overprints of Egyptian stamps, with Palestine in Arabic and English. Egypt primarily employed definitives, with one express stamp, picturing a motorbike, and airmail stamps featuring King Farouk.[113]

In the West Bank, prior to its incorporation into Jordan in 1950, Jordanian authorities issued stamps from 1948 until April 1950. With overprints of "Palestine" in Arabic and English, the Jordanians used definitives, postage dues, and obligatory tax stamps.[114]

Israel

From May 16, 1948, stamps were issued by the State of Israel under the Israel Postal Authority. The first set of stamps were entitled Doar Ivri (lit. "Hebrew postage"), as pictured, while later stamps are issued for Israel. Israeli stamps are trilingual, in Arabic, English and Hebrew, following the practice of the British Mandate of Palestine. Israel Post first issued postage due stamps, tete-beche and gutter pairs in 1948, airmail stamps in 1950, official mail stamps in 1951 and provisional stamps in 1960. The Israel Defense Forces operate a military postal system but, in 1948, dropped plans to print their own stamps.

In 1955, Israel's first mobile post office began in the Negev. By 1990, Israel ran 53 routes for 1,058 locations, including Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza.[115] Due to hyperinflation, in 1982 and 1984 Israel issued non-denominated stamps.[116] During the 1990s, Israel experimented with vending machines for postal labels (franking labels).

The country produced a total of 110 new issues in the 1960s, 151 in the 1970s, 162 in the 1980s and 216 in the 1990s. More than 320 new stamps have been created since 2000. Israel stamps have distinctive tabs, on the margins of printed sheets, with inscriptions in Hebrew and usually English or French.[117] The design of national and local postmarks is also popular.

From 1967 until 1994, Israel operated postal services in the occupied territories of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. It continues to operate postal services in occupied East Jerusalem and the Syrian Golan Heights.

Palestinian National Authority

Starting in 1994, the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) established post offices throughout the PNA, developed its own unique postmarks and issued stamps. The PNA has issued dozens of stamps and souvenir sheets since 1994, with the exception of 2004 and 2007.[118]

The PNA is authorized to issue manage postal operations, issue stamps and postal stationery, and set rates, under agreements signed between Israel and the PNA following the Oslo Accords. In 1999, the PNA and Israel agreed that PNA mail could be sent directly to Egypt and Jordan.[119] The PNA's Ministry of Telecom & Information Technology has sharply criticized postal services in areas under Israeli control.[120][121]

Despite some initial doubts in philatelic circles, the PNA stamps came to be used for postal activities within Palestine and for international postal communications as well. The Universal Postal Union and its member countries generally do not recognize stamps issued by administrations that have not achieved full independence, though the UPU maintains ties and supports these administrations.[15]

State of Palestine stamps

On January 9, 2013, the first stamp with the "State of Palestine" wording was issued by Palestinian postal service.[122] The move came following the historic upgrade of Palestine mission of PLO (Palestinian Authority) to the UN to non-member observer state on 29 November 2012.

Propaganda Labels

Labels issued by The Jewish National Fund

The Jewish National Fund (JNF) produced and sold thirty million labels between 1902 and 1914 as "promotional materials" to "help spread the message of Zionism."[123] The "Zion" label was its biggest seller with 20 million copies of this blue-and-white label with the Star of David and the word "Zion" sold. Four million copies of the "Herzl" label, issued between 1909 and 1914, were sold. The label depicted Theodor Herzl gazing at a group of workers in Palestine, using the famous image of him on the Rhine Bridge from the First Zionist Congress, superimposed onto a scene of a balcony overlooking the Old City of Jerusalem. Labels with pictures of Max Nordau, David Wolffsohn, the Wailing Wall, a map of Palestine, and historical scenes and landscape in Palestine, sold about one million copies each.[123] A total of 266 different labels were produced by the JNF's Head Office in Jerusalem between 1902 and 1947.[124]

Anglo Palestine Company

Labels were also issued by the Anglo Palestine Company (APC), the forerunner to Israel's Bank Leumi. In 1915, Ahmed Djemal, who ruled over Syria and Palestine on behalf of the Ottoman Empire, issued an anti-Zionist proclamation ordering the "confiscation of the postage stamps, Zionist flags, paper money, bank notes of the Anglo-Palestine Company, Ltd. in the form of checks which are spread among these elements and has decreed the dissolution of all the clandestine Zionist societies and institutions ..."[125] After World War I, the APC relied on the postage stamps of British authorities, which were marked with an APC perforation, as shown here.

Labels issued by Arab Organisations

During the Mandate period, Arab groups issued four distinct propaganda labels (or series): a promotional label for the Jerusalem Arab Fair (April 1934), a series of five labels issued by the Financial Department of the Arab Higher Committee (Beit al-Mal al-'Arabi, 1936), a series of three labels issued by the Arab Community Fund (Sandouk al-Umma al-'Arabi, no date known), and a series of five labels (1, 2, and 5 Mils; 1 and 2 US-Cents) inscribed Palestine For The Arabs and depicting the Dome of the Rock and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in front of a map of Palestine (Jaffa, 1938).[126][127]

After 1948, Arab organizations issued numerous propaganda labels, so the following lists may be incomplete:

Syria and Lebanon Day (one label, no date known, 1940s?), Islamic Orphan House (five labels, no date known, 1940s?), General Union of Palestine Workers (one label, 5 Fils, no date known, 1960s?), Charitable Association for the Families of Prisoners and Detainees (one label, depicting a mother and child, no date known, 1960s?).[127]

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) issued in Gaza a 5 Mils label depicting a map and sun (1964).[127] Fateh (Palestinian National Liberation Movement) issued a number of series: ten labels (1968–69) and a sheet of four (1969?), mainly on the battle of Karameh,[128][129] a series of three label commemorating the fifth anniversary of Fateh (1970, motif: Mandate stamps).[129]

Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) issues: set of four labels issued in 1969[127] or 1970.[128] The labels Charitable Association for the Families of Prisoners and Detainees were issued in the 1970s with the PFLP name in English (two labels: 5 US-Cents and 5 US-$), followed by seven labels commemorating Ghassan Kanafani (1974), a sheet of 25 labels depicting martyrs (1974) and a sheet of 12 labels with city views (1975).[127]

Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) issued two sets of labels in the 1970s: five labels depicting martyrs and two labels with freedom fighters in font of the globe.[129] The Palestinian Popular Struggle Front (PPSF) contributed two sets of labels with motifs Leila Khaled and party symbols (map, gun, Dome of the Rock).[129] Other groups issuing propaganda labels in the 1970s include Organization for Arab Palestine and Action Organization for the Liberation of Palestine.[129]

During the 1980s, at least 18 different labels pertain to the First Intifada.[129] For example, label sheets and miniature sheets reproduce the Mandate's 1927 Pictorials with overprints in English, French, German, and Arabic: Intifadah 7 December 1987 and Declaration of Statehood 15 November 1988.[130]

See also

Notes, references and sources

- Notes

- ^ [i]From 1918-22, the area today known as Jordan was part of the British Mandate of Palestine, before it was separated out to form the Emirate of Transjordan. Unless otherwise specified, this article uses "British Mandate" and related terms to refer to the post-1922 mandate, west of the Jordan river.

- References

- ↑ Bristowe, 2003, p. 24.

- ↑ Hitti, 2004, p. 220.

- ↑ Yoder, 2001, p. 42.

- ↑ Esther III:13, VIII:10–14, IX:20

- ↑ Hitti, 2004, p. 457.

- ↑ Levy, 1995, p. 516.

- ↑ "Dictionaries". Sakhr. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- 1 2 Silverstein, 2007, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Hitti, 1996, p. 240.

- ↑ Runciman, 2006, p. 263.

- ↑ Gibbon, 1837, p. 1051.

- ↑ Shahin, 2005, pp. 421–423.

- ↑ Oliver, 2001, p. 17.

- ↑ Brown, 1979, p. 81.

- 1 2 3 4 Barth Healey (1998-07-19). "Philatelic Diplomacy: Palestinians Join Collectors' List". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- 1 2 Levy, 1998, p. 536.

- 1 2 Collins & Steichele, 2000, pp. 17-21.

- 1 2 Collins & Steichele, 2000, p. 17.

- ↑ Collins & Steichele, 2000, p. 21

- ↑ Collins & Steichele, 2000, p. 21-22, quoting Tobias Tobler Memorabilia from Jerusalem, 1853.

- 1 2 Collins & Steichele, 2000, p. 22.

- 1 2 Tranmer, 1976, p. 54.

- 1 2 Lindenberg, 1926, p. 15.

- ↑ tartar or tatar refers to a despatch rider, not the ethnic group Tatars

- 1 2 3 4 Porter, 1858, p. 1viii.

- ↑ Collins & Steichele, 2000, p. 25.

- ↑ Collins & Steichele, 2000, p. 23.

- 1 2 Collins & Steichele, 2000, pp. 201-202.

- ↑ Collins & Steichele, 2000, p. 202.

- ↑ Birken, 2007, Vol. Beyrut, pp. 29-30, 37.

- ↑ Steichele, 1977-1981, p. 1015.3

- 1 2 Collins & Steichele, 2000, p. 13.

- ↑ Steichele, 1977-1981, p. 1015.4.

- ↑ Steichele, 1991, pp. 347, 348, 352, 371.

- ↑ Lindenberg, 1926, pp. 38-39.

- ↑ Steichele, 1991, pp. 240, 246, 267.

- ↑ Lindenberg, 1926, p. 29.

- ↑ Steichele, 1991, pp. 240, 246, 267, 285.

- ↑ Steichele, 1991, pp. 261, 265, 267, 285.

- 1 2 Lindenberg, 1926, p. 35.

- ↑ Tranmer, 1976, p. 72.

- ↑ Tranmer, 1976, pp. 59-62.

- ↑ Steichele, 1991, pp. 240.

- ↑ Tranmer, 1976, p. 55 lists only Rishon Le Zion, Petah Tiqva, Gedera, and Zichron Yaacov.

- ↑ Tranmer, 1976, pp. 55-66.

- ↑ Tranmer, 1976, p. 57.

- ↑ Lindenberg, 1926, pp. 30-32.

- ↑ Steichele, 1990, pp. 133, 134, 161, 163, 175.

- 1 2 Lindenberg, 1926, pp. 25-26.

- ↑ Forsyth, 1861, p. 117.

- ↑ Letter by A.J. Revell. In: Thamep Magazine, Vol. 2, no. 2, March/April 1958, p.360.

- ↑ Steichele, 1990, pp. 33, 45.

- ↑ Lindenberg, 1926, p. 18.

- ↑ Steichele, 1990, pp. 66, 70, 76, 72, 78, 81, 83.

- ↑ Steichele, 1990, pp. 33, 87.

- ↑ Rachwalsky & Jacobs, 1962.

- ↑ Steichele, 1990, p. 63

- ↑ Lindenberg, 1926, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Steichele, 1990, p. 66.

- ↑ Steichele, 1991, p. 198.

- ↑ Lindenberg, 1926, p. 27.

- ↑ Rachwalsky, 1957

- ↑ Steichele, 1991, p. 200.

- ↑ Lindenberg, 1926, p. 28.

- ↑ Steichele, 1990, p. 13.

- ↑ Steichele, 1990, p. 14.

- ↑ Michael M. Sacher. "The Egyptian post office in Jaffa" in The BAPIP Bulletin. No. 83, 1975, p. 14

- ↑ Steichele, 1990, p. 15.

- ↑ Lindenberg, 1926, pp. 16-18.

- 1 2 Dorfman, 1989, p. 5.

- ↑ Hoexter, 1970, p. 4

- ↑ Dorfman, 1989, p. 7.

- ↑ Hoexter, 1970, pp. 4, 28

- ↑ Dorfman, 1989, p. 8.

- ↑ Hoexter, 1970, pp. 5-7.

- ↑ Dorfman, 1989, p. 17.

- ↑ Hoexter, 1970, p. 25.

- ↑ Mayo, 1984, p. 24.

- ↑ Dorfman, 1989, p. 20.

- ↑ Fisher, 1999, p. 215.

- 1 2 Dorfman, 1989, p. 23.

- ↑ Tobias Zywietz (2007-03-21). "The First Overprint Issue "Jerusalem I" (1920)". Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ↑ (See Article 22 of the Palestine Mandate)

- ↑ Cohen, 1951.

- ↑ Dorfman, 1989, p. 73.

- ↑ Dorfman, 1989, p. 74.

- ↑ Donald M. Reid (April 1984). "The Symbolism of Postage Stamps: A Source for the Historian". Journal of Contemporary History. 19:2: 236.

- ↑ Proud, 2006, p. 14.

- ↑ Baker, 1992, p. 187.

- ↑ Proud, 2006, p. 15.

- ↑ Proud, 2006, p. 17.

- ↑ Hochhheiser, Arthur M, Postal Stationery of the Palestine Mandate, The Society of Israel Philatelists, 1984

- ↑ The 1944-48 Palestine Airletter Sheet, Tony Goldstone

- ↑ Rosenzweig, 1989, p. 136.

- ↑ Ernst Fluri, 1973, pp. 6-7.

- ↑ Tobias Zywietz. "The Postal Situation (1948-1967)" in A Short Introduction To The Philately Of Palestine.

- ↑ Marcy A. Goldwasser. The French Connection. In: The Jerusalem Post, August 28, 1992.

- ↑ Ascher, Siegfried; Mani, Walter (1966). "Französische Konsulatspost in Jerusalem". Der Israel-Philatelist. Roggwil, Switzerland: Schweizerischer Verein der Israel-Philatelisten. 4 (17): 292–296.

- ↑ Livnat, Raphaël (2006). "Jérusalem postes françaises 1948 : l'examen des critiques". Documents Philatéliques. Paris (192): 3–17.

- ↑ Fluri, 1973, pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Ian Kimmerly. Jewish National Fund issues postal substitute. In: The Globe and Mail (Canada), July 22, 1989.

- ↑ Fluri, 1973, pp. 15-16.

- ↑ Fluri, 1973, pp. 13-14.

- 1 2 Fluri, 1973, p. 10.

- ↑ Fluri, 1973, p. 11.

- ↑ Marcy A. Goldwasser. Seals of Approval. In: The Jerusalem Post, June 18, 1993.

- ↑ Livni, Israel (1969). Livni's Encyclopedia of Israel Stamps. Tel-Aviv: Sifriyat Ma'ariv. pp. 13–21.

- ↑ Marcy A. Goldwasser. The Emergency Stamp of Safed. In: The Jerusalem Post, November 6, 1992.

- ↑ A. Ben-David, 1995, p. 71-74.

- ↑ A. Ben-David, 1995, p. 74.

- ↑ Marcy A. Goldwasser. Armored Car Mail. In: The Jerusalem Post, January 17, 1992.

- 1 2 A. Ben-David, 1995, p. 71.

- ↑ Zywietz, Tobias. "Egyptian: Definitives, Air & Express Stamps 1948" in A Short Introduction To The Philately Of Palestine.

- ↑ Zywietz, Tobias. "Jordanian Occupation: Definitives 1948" in A Short Introduction To The Philately Of Palestine.

- ↑ Marcy Goldwasser. "Have Stamps, Will Travel” in The Jerusalem Post, August 10, 1990

- ↑ Siegel, Judy (1989-10-16). "Postal Authority To Push Its 'Post-Inflation' Stamps". The Jerusalem Post. The date and design information is drawn from the IPF catalog.

- ↑ Israel Philatelic Federation catalog

- ↑ Zywietz, Tobias. "A Short Introduction To The Philately Of Palestine: PNA Post Offices and Postmarks". Zobbel. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ↑ Najat Hirbawi, ed. "Chronology of Events." Palestine-Israel Journal 6:4 1999

- ↑ ?

- ↑ "Palestinian ministers detail damage caused by Israel; face deputies' criticism". BBC Worldwide Monitoring. 2008-05-01.

- ↑

- 1 2 Berkowitz, 1993, pp. 166–167.

- ↑ Bar-Gal, 2003, p. 183.

- ↑ Sicker, 1999, p. 118.

- ↑ Palestine Stamps 1865-1981, p. 14

- 1 2 3 4 5 Abuljebain, 2001, p. 26

- 1 2 Palestine Stamps 1865-1981, p. 19

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Abuljebain, 2001, p. 27

- ↑ Abuljebain, 2001, p. 57

- Sources

- Abuljebain, Nader K. (2001). Palestinian history in postage stamps = تاريخ فلسطين في طوابع البري. Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies/Welfare Association.

- Aron, Joseph (1988). Forerunners to the forerunners: a pre-philatelic postal history of the Holy Land. Jerusalem: Society of the Postal History of Eretz Israel.

- BALE : the stamps of Palestine Mandate 1917–1948, 9th ed. (2000). Joseph D. Stier (ed.). Chariot. ISSN 1350-679X.

- Bar-Gal, Yoram (2003). Propaganda and Zionist Education: The Jewish National Fund. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 1-58046-138-7.

- Ben-David, Arieh (1995). Safad : the transition period from the termination of the British Mandate until the implementation of the State of Israel postal service. World Philatelic Congress of Israel, Holy Land, and Judaica Societies.

- Berkowitz, Michael (1993). Zionist Culture and West European Jewry Before the First World War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42072-5.

- Birken, Andreas (2003). Die Poststempel = The postmarks. Volumes Beirut and Suriye. Hamburg: Arbeitsgemeinschaft Osmanisches Reich/Türkei, ©2007. (CD-ROM)

- Bristowe, Sydney (2003). Sargon the Magnificent. Kessinger. ISBN 0-7661-4099-7.

- Brown, Reginald A. (1979). Proceedings of the Battle Conference on Anglo-Norman Studies. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 0-8476-6184-9.

- Cohen, Israel (1951). A Short History of Zionism. London.

- Coles, John H. and Howard E. Walker (1987). Postal cancellations of the Ottoman Empire. Part 2: the lost territories in Africa and Asia. London & Bournemouth: Christie's Robson Lowe. ISBN 0-85397-426-8.

- Collins, Norman J. and Anton Steichele (2000). The Ottoman post and telegraph offices in Palestine and Sinai. London: Sahara. ISBN 1-903022-06-1.

- Collins, Norman J. (1959). Italian ship mail from Palestine and Israel.. In: The BAPIP Bulletin. No. 28.

- Dorfman, David (1985). Palestine Mandate postmarks. Sarasota, Fla.: Tower Of David.

- Dorfman, David (1989). The postage stamps of Palestine: 1918–1948.

- Firebrace, John A. (1991). British Empire campaigns and occupations in the Near East, 1914–1924: a postal history. London & Bournemouth: Christie's Robson Lowe. ISBN 0-85397-439-X.

- Fisher, John (1999). Curzon and British Imperialism in the Middle East, 1916-1919. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-4875-2.

- Fluri, Ernst (1973). The minhelet ha’am period : (1 to 15 May 1948). World Philatelic Congress of Israel, Holy Land and Judaica Societies.

- Forsyth, James B. (1861). A Few Months in the East, Or, A Glimpse of the Red, the Dead, and the Black Seas. University of Michigan.

- Gibbon, Edward (1837). The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Oxford University.

- Goldstein, Carlos and Emil S. Dickstein (1983). Haifa and Jaffa postmarks of the Palestine Mandate. Beachwood, Oh.: Society of Israel Philatelists.

- Groten, Arthur H. (1988). The postmarks of Mandate Tel Aviv. Beachwood, Oh.: Society of Israel Philatelists.

- Hitti, Phillip K. (1996). The Arabs: A Short History. Regnery Gateway. ISBN 0-89526-706-3.

- Hitti, Phillip K. (2004). History of Syria, Including Lebanon and Palestine. Gorgias. ISBN 1-59333-119-3.

- Hoexter, Werner (1970). The stamps of Palestine: I. The stamps issued during the period of the military administration (1918 to 1 July 1920). World Philatelic Congress of Israel, Holy Land, and Judaica Societies.

- Ideology and Landscape in Historical Perspective. Alan R. Baker and Gideon Biger; editors. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41032-0.

- Levy, Thomas E. (1995). The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land. Continuum. ISBN 0-7185-1388-6.

- Lindenberg, Paul P. (1926). Das Postwesen Palästinas vor der britischen Besetzung. Vienna: Die Postmarke.

- Mayo, Menachim M. (1984). Cilicie : occupation militaire francaise. New York.

- Oliver, Anthony R. and Anthony Atmore (2001). Medieval Africa, 1250-1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79372-6.

- Palestine: Stamps (1865–1981). Beirut: Dar Al-Fata Al-Arabi, 1981.

- Shaath, Nabeel Ali and Hasna' Mikdashi (1981). Palestine: Stamps (1865–1981). Beirut: Dar al-Fata al-Arabi, 1985 (2nd ed.)

- Porter, Josias L. (1858). A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine. Harvard University.

- Proud, Edward B. (2006). The postal history of Palestine and Transjordan. Heathfield. ISBN 1-872465-89-7. First edition (1985): The postal history of British Palestine 1918-1948.

- Rachwalsky, E. (1957). Notes on the Italian post office in Jerusalem. In: The BAPIP Bulletin. No. 21, pp. 16–18.

- Rachwalsky, E. and A. Jacobs (1962). The civilian German postal services in Palestine, 1898-1914. In: BAPIP Bulletin. No. 39, pp. 5–8, and no, 40, pp. 12–13.

- Reid, Donald M. (1984). The symbolism of postage stamps: A source for the historian. In: Journal of Contemporary History, 19:2, pp. 223–249.

- Rosenzweig, Rafael N. (1989). The Economic Consequences of Zionism. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-09147-5.

- Runciman, Steven and Elizabeth Jeffreys (2006). Byzantine style, religion and civilization : in honour of Sir Steven Runciman. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83445-7.

- Sacher, Michael M. (1995). The postal markings of Mandate Palestine: 1917-1948. London: Royal Philatelic Society. ISBN 0-900631-30-9.

- Shahin, Mariam (2005). Palestine: A Guide. Interlink. pp. 421–423.

- Siegel, Marvin (1964). The "postage paid" markings of Palestine and Israel. In: The BAPIP Bulletin. No. 45, p. 16.

- Sicker, Martin (1999). Reshaping Palestine: From Muhammad Ali to the British Mandate, 1831-1922. Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-96639-9.

- Silverstein, Adam J. (2007). Postal Systems in the Pre-Modern Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85868-2.

- Steichele, Anton (1990/1991). The foreign post offices in Palestine : 1840–1918. 2 vols. Chicago: World Philatelic Congress of Israel, Holy Land, and Judaica Societies.

- Tranmer, Keith (1976). Austrian post offices abroad : part eight ; Austrian Lloyd, Liechtenstein, Cyprus, Egypt, Palestine, Syria-Lebanon, Asia Minor. Tranmer.

- Yoder, Christine E. (2001). Wisdom As a Woman of Substance: A Socioeconomic Reading of Proverbs 1-9. deGruyter. ISBN 3-11-017007-8.

- Zywietz, Tobias. A Short Introduction To The Philately Of Palestine

Further reading

- 20th anniversary publication, World Philatelic Congress of Israel Holy Land & Judaica Societies. World Philatelic Congress of Israel, Holy Land and Judaica Societies. Downsview, Ont., Canada: The WPC, 1986.

- Ashkenazy, Danielle. Not Just for Stamp Collectors. Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Feb. 25 1999. See also Israeli government description.

- Bale, Michael H. (ed.). Holyland catalogue: stamps & postal history during the rule of the Ottoman Empire: Turkish & foreign post offices. Tel-Aviv: Chariot Global Marketing, 1999.

- Bard, Dr. Leslie A. Commercial Airmail Rates from Palestine to North America : 3 August 1933 to 30 April 1948. In: Israel Philatelist. 57:5, Oct

- Blau, Fred F. The air mail history of the Holyland. [Chicago]: 1988.

- Blau, Fred F. The Allied Military Air Mail to and from Palestine in WWII. In: Holy Land Postal History 1987 Autumn.

- Blau, Fred F. Air accident mail to and from Palestine and Israel. In The BAPIP Bulletin. No. 107-8, 1984

- Hirst, Herman H. and John C.W. Fields Palestine and Israel: Air Post History [review]. In: The BAPIP Bulletin. No. 8, 1954, p. 29.

- Lachman, S. Postage rates in Palestine and Israel. In: The BAPIP Bulletin. No. 2, 1952, p. 13–14

- McSpadden, Joseph Walker (1930). How They Carried the Mail: From the Post Runners of King Sargon to the Air Mail of Today. University of California.

External links

- A Short Introduction to the Philately of Palestine (includes links for Collectors Societies and extensive bibliography)

- Society of Israel Philatelists (SIP)

- Cercle Français Philatélique d'Israël (CFPI) (fr)

- Oriental Philatelic Association of London (OPAL)

- Ottoman and Near East Philatelic Society (ONEPS)

- Sandafayre Stamp Atlas: Palestine

- The 1944 - 48 Palestine Airletter Sheet by Tony Goldstone