Murray Island, Queensland

| Native name: <span class="nickname" ">Mer | |

|---|---|

|

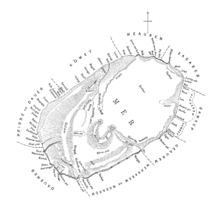

A satellite images of Murray Island | |

A map of the Torres Strait Islands showing Mer in the northeastern waters of Torres Strait | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Northern Australia |

| Coordinates | 9°55′S 144°3′E / 9.917°S 144.050°ECoordinates: 9°55′S 144°3′E / 9.917°S 144.050°E |

| Archipelago | Torres Strait Islands |

| Adjacent bodies of water | Torres Strait |

| Total islands | 3 |

| Major islands | 1 |

| Area | 4.29 km2 (1.66 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 234 m (768 ft) |

| Highest point | Gelam Paser |

| Administration | |

|

Australia | |

| State | Queensland |

| Regional Authority | Torres Strait Regional Authority |

| Local Government Area | Torres Strait Island Region |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 485 (2006 census) |

Murray Island, also called Mer in the native Meriam language, is a small island of volcanic origin of the Torres Strait Islands archipelago that is located in the eastern section of Torres Strait, near the Great Barrier Reef. The island is populated by the Melanesian Meriam people, which has a population of around 485 as of 2006 census. The Murray Group comprises three islands: Mer, Dauar and Waier.

There are eight Meriam clans: Komet, Zagareb, Meuram, Magaram, Geuram, Peibre, Meriam-Samsep, Piadram, and Dauer Meriam. The organisation of the island is based on the traditional laws of boundary and ownership. Administrative control of the island rest with the Torres Strait Regional Authority.

Geography

Murray Island is a basaltic island formed from an extinct volcano, which was last active over a million years ago. It formed as a result when the Indo-Australian Plate slid over the East Australia hotspot. The island rises to a plateau 80 metres (260 ft) above mean sea level.

The highest point of the island is the 230-metre (750 ft) Gelam Paser, the western end of the volcano crater. The island has red fertile soil and is covered in dense vegetation. The island has a tropical climate with a wet and dry season.

History

Pre-European settlement

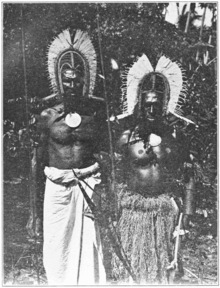

Murray Island has been inhabited for around 2800 years, the first settlers being Papuo-Austronesians who brought agriculture and pot making with them. Regular contact between the inhabitants of Torres Strait (including Murray Island, known by the Meriam people as Mer Island), Europeans, Asians and other outsiders began once the Torres Strait became a means of passage between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean in the 19th Century.

The inhabitants of the Torres Strait, including the Meriam people, gained a reputation as fierce warriors and skilled mariners. Warfare (both intertribal and against European ships in transit through the Coral Sea) and head hunting were part of the culture of all Torres Strait islanders. The account of Jack Ireland, a surviving cabin boy from the barque Charles Eaton that was wrecked in 1834 at Detached Reef near the entrance to Torres Strait is of interest in this respect. He spent much of his time on Murray Island before being rescued.

A large ceremonial mask was recovered in 1836 from a neighbouring island - Aureed (Skull) Island, following his rescue and that of young William D'Oyley, the only other survivor of the Charles Eaton, and their return to Sydney. The mask was made of turtle shells surrounded by numerous skulls, seventeen of which were determined as having belonged to the crew and passengers of the Charles Eaton who were massacred when they came ashore following the shipwreck. The mask was entered into the collection of the Australian Museum after the skulls were buried on 17 November 1836 in a mass grave in the Sydney cemetery in Devonshire Street. An appropriate monument - in the form of a huge altar stone - recording the catastrophe by which they perished was erected. When the Devonshire Street Cemetery was resumed for the site of the Central Railway Station in 1904 the skulls and the monument were removed to Bunnerong Cemetery at Botany Bay Sydney.[1]

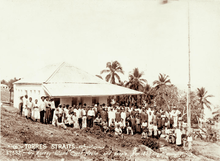

Post European settlement (1872)

Missionaries (mainly Polynesian) and some other Polynesians began to settle on the island in 1872 when the London Missionary Society founded a missionary school there.[2] The Queensland Government annexed the islands in 1879. Tom Roberts, the well-known Australian painter, visited the island in 1892.[3] He witnessed a night-time dance and depicted it in a painting.

In 1936, a maritime strike fuelled by Islander dissatisfaction with the fact that their wages and boats were managed by the Protector of Aborigines allowed islanders to assert control and reject government controls. In 1937, the inaugural meeting of Island Councillors on Yorke Island resulted in the Torres Strait Islander Act (1939), giving Islanders more authority in their own affairs and established local governments on each island.

After the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941, over 700 Islanders volunteered to defend the Torres Strait. This group was organised into the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion. The migration of Islanders to mainland Australia increased as jobs disappeared in the pearling industry. A call for independence from Australia in the 1980s was due to the government failing to provide basic infrastructure on the island.

Murray Island's most famous resident was trade unionist Eddie Mabo, whose decision to sue the Queensland Government to secure ownership of his land, which had been removed from his ancestors by the British colonial powers using the terra nullius legal concept, ultimately led to the High Court of Australia, on appeal from the Supreme Court of the State of Queensland, issue the "Mabo decision" to finally recognise Mabo's rights on his land on 3 June 1992. This decision continues to have ramifications for Australia. Mabo himself died a few months before the decision. After vandalism to his grave site, he was reburied on Murray Island where the islanders performed a traditional ceremony for the burial of a king.[4]

Culture

The people of Mer maintain their traditional culture. Modern influences such as consumer goods, television, travel and radio are having an impact on traditional practices and culture. Despite this, song and dance remains an integral part of island life and is demonstrated through celebrations such as Mabo Day, Coming of the Light, Tombstone openings and other cultural events. In 2007, after two years of negotiations, the skulls of five Islander tribesmen were returned to Australia from a Glasgow museum where they had been archived for more than 100 years.[5]

The artist Ricardo Idagi was born on Murray Island.[6] Idagi won the main prize at the Western Australian Indigenous Art Awards in 2009.

Language

The people of Murray Island speak Torres Strait Creole and Meriam, a member of the Eastern Trans-Fly languages of Trans–New Guinea; its sister languages being Bini, Wipi and Gizrra. Though it is unrelated to Kalaw Lagaw Ya of the Central and Western Islands of Torres Strait, the two languages share around 40% of their vocabulary. Torres Strait English is a second language.

Governance

Murray Island is governed by the Community Council, which is responsible for roads, water, housing and community events. The Community Council is an integral part of community life. The elders of the community hold a position of respect and also have a major influence on island life.

See also

References

- ↑ McInnes, Allan (1983). The Wreck Of The Charles Eaton. Windsor: Diamond Press. p. 45.

- ↑ "Torres Strait Island communities I-M". State Library of Queensland. 11 May 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ↑ Bousen, Mark (6 March 2010). "118-year-old Murray Island art discovered". Torres News. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ↑ "Queenslander". News Limited. 13 June 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ↑ "Mer Islanders reclaim sacred skulls". Torres News. 3 July 2007. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ↑ Rothwell, Nicolas (1 October 2009). "Carved out of ancestral whispers". The Australian. News Limited. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

External links

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Social Justice Reports 1994–2009 and Native Title Reports 1994–2009 for more information about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs

.png)