Monte Cristo, Washington

| Monte Cristo | |

|---|---|

| Ghost Town | |

|

Townsite in 2014 | |

Monte Cristo  Monte Cristo | |

| Coordinates: 47°59′8″N 121°23′38″W / 47.98556°N 121.39389°WCoordinates: 47°59′8″N 121°23′38″W / 47.98556°N 121.39389°W | |

| Elevation[1] | 842 m (2,762 ft) |

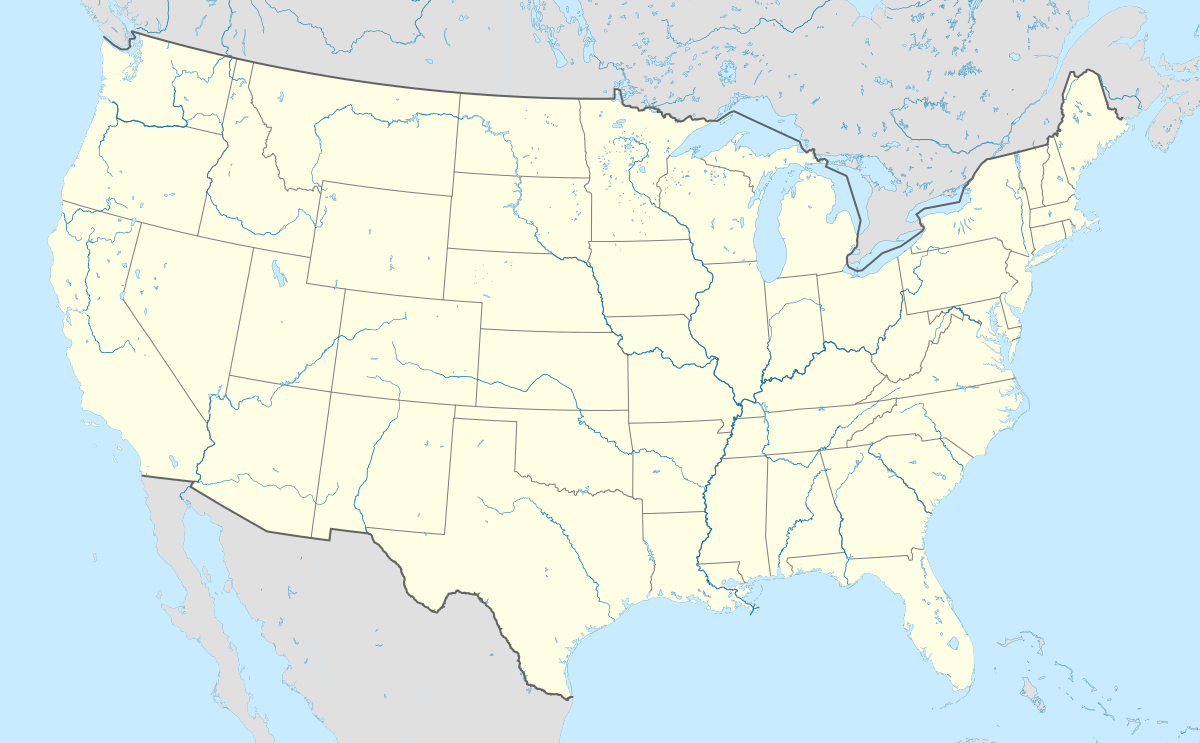

Monte Cristo is a ghost town northwest of Monte Cristo Peak, in eastern Snohomish County in western Washington.

Prospecting in the region began in the Skykomish River drainage with the Old Cady Trail used for access. In 1882 Elisha Hubbard improved the trail up the North Fork Skykomish, from Index to Galena, then north up the tributary Silver Creek. A boom shortly followed at Mineral City. The mineral belt was traced in various directions, including north over the divide between the Skykomish and Sauk River drainages. In the early summer of 1889 Joseph Pearsall saw glittering deposits and traced them north to Seventysix Gulch and the area that became Monte Cristo. A frenzy of claim staking quickly followed. In 1890 many miners hiked to Monte Cristo from the south by way of Index, Galena, and Mineral City, crossing the divide at first via Wilmans Pass and later via Poodle Dog Pass. In the fall of 1891 a narrow wagon road called the Wilmans or Pioneer Trail was completed from Sauk City on the Skagit River to Monte Cristo, allowing access from the north. A key stop on this road was the trading post at Orient, at the forks of the Sauk River. Today this area is known as Bedal. In the summer of 1891 it was discovered that Monte Cristo could be accessed via the South Fork Stillaguamish River. A surveyor named M.Q. Barlow blazed a route from Silverton to Monte Cristo. Mining interests Thomas Ewing and George W. Grayson, then Judge Edward Blewett, Judge Hiram G. Bond of Denver and New York City, and Seattle publisher Leigh S. J. Hunt, funded further work and soon a wagon road was built over Barlow Pass to join the Sauk wagon road. Later a railroad would be built over the same route.[2]

Monte Cristo was the first live mining camp on the west slopes of the Cascade Range. There were 13 mines and 40 claims by 1891. By 1893 there were 211 mining claims. The boom required money from the eastern United States to continue to grow.[2] In 1891 John D. Rockefeller became interested in Monte Cristo. His syndicate, Colby and Hoyt, took over the primary mines, including the Pride and Mystery mines. The Wilmans brothers were paid $470,000.[2] Rockefeller's companies acquired a controlling two-thirds interest in the best properties.[3][4] Frederick Trump (grandfather of Donald Trump) was also active in the town; he operated a boom-town hotel and brothel there.[5]

During the 1890s hopes ran high at Monte Cristo. It was widely believed that the area would become the greatest lead-silver district in the Western Hemisphere.[2] Elaborate cable-bucket aerial tramways were built over Mystery Ridge for hauling ore to the town site, carrying as much as 230 tons every day. A five-level concentrator was completed in 1894 at the Monte Cristo townsite. Ore was shipped out via the newly completed railway, 42 miles long from Monte Cristo to Hartford. The boom peaked in 1894, at which time the town's population was well over 1,000. In 1895 there were 125 men employed in the mines with a monthly payroll of $10,500. Employment rose to 200 in 1896. Mining activity indirectly supported about 600 people.[2]

The year 1896 was prosperous but in November major flooding damaged or destroyed railroad tunnels and track. Mining output reached record levels in 1897 but again intense autumn floods devastated the region's infrastructure, the repair of which cut deeply into mining profits. Other problems such as metallic impurities at the Monte Cristo concentrator and the Everett smelter led to the boom collapsing. By 1900 most of the Monte Cristo miners had left for the new mining booms of the Klondike.[2]

Miners and geologists had made mistakes in judging the potential of Monte Cristo's mineral wealth. There were rich surface deposits but they did not continue far into the ground. Mining below about 500 feet turned out to be seldom worth the effort.[2] Mining operations ceased in 1907, probably related to the Panic of 1907. The town survived as a tourist destination for several more decades, but the county road was flooded out in 1980, and the only remaining business in town, a lodge, burned down in 1983. That same year, a nonprofit group called Monte Cristo Preservation Association stepped in to save and restore the historical site.[6]

Very few original structures are still standing, but the four-mile-long road (as noted in driving directions)[7] into town remains popular with hikers and mountain bikers. The road is impassable to vehicles as the shore on either side of the bridge washed out several years ago. The bridge remained standing, however hikers and mountain bikers now either have to wade thru the river or cross via fallen trees in order to continue onto the old town-site from the Barlow Pass entry.

Extensive plans for removing pollution from mine tailings have been written, and include removal and/or containment of pollution in remote mine sites in the nearby Glacier Basin. A new access road is part of the plans for the cleanup.[8] Cleanup of arsenic and other toxins left behind began in September 2012.[6]

Mines that are not caved in are: Boston American Mine, Justice Mine, Mistery Mine, and New Discovery Tunnel.

Notes

- ↑ "Monte Cristo". Geographic Names Information System. USGS. Retrieved 2008-10-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Beckey, Fred (2003). Cascade Alpine Guide: Climbing and High Routes: Stevens Pass to Rainy Pass (3rd ed.). The Mountaineers. pp. 25–30. ISBN 0-89886-423-2.

- ↑ Cameron, David A. (January 2, 2008). "Monte Cristo -- Thumbnail History". HistoryLink. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ↑ Sykes, Karen (September 25, 1977). "History of Monte Cristo". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved 2008-10-29.

- ↑ Evan Bush (August 25, 2015). "Donald Trump's grandfather got business start in Seattle". Seattle Times. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- 1 2 Mulligan, Mark (September 16, 2012). "Cleanup begins of what Monte Cristo miners left behind". The Herald, Everett, Washington. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ↑ "Driving Directions from Everett, WA to Monte Cristo, WA". MapQuest. Retrieved 2008-10-29.

- ↑ Moyle, Phillip R.; Wasley, Dustin G. (April 2010). Engineering Evaluation / Cost Analysis, Monte Cristo Mining Area (PDF) (Report). Spokane, Washington: Cascade Earth Sciences. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

Further reading

- Woodhouse, Philip R. (July 1996). Monte Cristo. Seattle, WA: Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-89886-071-9.

- Woodhouse, Philip R.; Daryl Jacobson; Bill Petersen (September 2000). The Everett & Monte Cristo Railway. Hamilton,MT: Oso Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9647521-8-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Monte Cristo, Washington. |