Mark Twain House

|

Mark Twain House | |

|

The Mark Twain House | |

| |

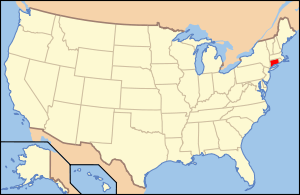

| Location | 351 Farmington Avenue, Hartford, Connecticut |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°46′1.7″N 72°42′1.8″W / 41.767139°N 72.700500°WCoordinates: 41°46′1.7″N 72°42′1.8″W / 41.767139°N 72.700500°W |

| Built | 1874 |

| Architect | Edward Tuckerman Potter |

| Architectural style | Victorian Gothic |

| Website | www.marktwainhouse.org |

| NRHP Reference # | 66000884 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[1] |

| Designated NHL | December 29, 1962[2] |

The Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford, Connecticut was the home of Samuel Langhorne Clemens (Mark Twain) and his family from 1874 to 1891. Designed by Edward Tuckerman Potter, the house was built in the American High Gothic style.[3] Clemens biographer Justin Kaplan has called it "part steamboat, part medieval fortress and part cuckoo clock."[4]

While living there, Clemens wrote his best-known works, including The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Prince and the Pauper, Life on the Mississippi, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, A Tramp Abroad, and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court.[5]

Poor financial investments prompted the Clemens family to move to Europe in 1891.[6] The Panic of 1893 further threatened their financial stability, and during 1895-1896, Clemens, his wife, Olivia, and their middle daughter, Clara, spent a year traveling so Clemens could lecture and earn the money to pay off their debts. Twain recounted the trip in Following the Equator (1897). Before the family could be reunited with their other two daughters, Susy and Jean, who had stayed behind, Susy died at home on August 18, 1896 of spinal meningitis. The family could not bring themselves to reside in the house after this tragedy and spent most of their remaining years living abroad. They sold the house in 1903.

The building later functioned as a school, an apartment building, and a public library branch. In 1929 it was rescued from possible demolition and put under the care of the newly formed Mark Twain Memorial, a nonprofit group. In 1962, the building was declared a National Historic Landmark.[2][7] A restoration effort led to its being opened as a house museum in 1974. In 2003 a multimillion-dollar, LEED-certified visitors' center was built that included a museum dedicated to showcasing Twain's life and work.[8]

The house faced serious financial trouble in 2008 due partly to construction cost overruns related to the new visitors' center,[9] but publicity about the museum's plight, quick reaction from the state of Connecticut, corporations and other donors, and a benefit performance organized by writers all helped the museum survive.[10] Since that time, the museum has reported improved financial conditions, though the recovery was marred by the 2010 discovery of a million-dollar embezzlement by the museum's comptroller, who pleaded guilty and served a jail term.[11]

In recent years the museum has claimed record-setting attendance levels.[12] It has featured events including celebrity appearances by Stephen King, Judy Blume, John Grisham and others; and sponsored writing programs and awards.[13]

In 2012 the Mark Twain House was named one of the Ten Best Historic Homes in the world in The Ten Best of Everything, a National Geographic Books publication.[14]

Life in the house

Mark Twain first came to Hartford in 1868 on business, while writing The Innocents Abroad, to work with publisher Elisha Bliss, Jr. of the American Publishing Company. At the time, Hartford was a publishing center with twelve publishers.[15] After marrying Olivia Langdon, Twain moved into a substantial home in Buffalo, New York. However, within two years, Twain considered moving to a more opulent house in Hartford.[16] He soon purchased the property in north Hartford, partly to be closer to his publisher, American Publishing Company.[17] Of Hartford, Twain said, "Of all the beautiful towns it has been my fortune to see, this is the chief... You do not know what beauty is if you have not been here."[18] He was attracted to the town which, at the time, had the highest per-capita income of any city in the United States.[16]

The family rented a house at what was called Nook Farm in 1871 before buying land there and building a new house.[15] They moved into the home in 1874 after its completion.[16] The top floor was the billiards room and his private study, where Twain would write late at night; the room was strictly off limits to all but the cleaning staff. It was also used for entertaining male guests with cigars and liquor. Twain had said "There ought to be a room in this house to swear in. It's dangerous to have to repress an emotion like that."[19]

The children had their own area, with a nursery and a playroom/classroom. Mrs. Clemens tutored her daughters in the large school room on the second floor.[20] Clemens played with his children in the conservatory, pretending to be an elephant in an imaginary safari. Twain noted the house "was of us, and we were in its confidence and lived in its grace and in the peace of its benediction."[21]

Clemens enjoyed living in the house, partly because he knew many different authors from his Hartford neighborhood, such as Harriet Beecher Stowe who lived next door and Isabella Beecher Hooker.[22] He also hosted several authors as guests, including Thomas Bailey Aldrich, George Washington Cable, and William Dean Howells, as well as actors Henry Irving, Lawrence Barrett, and Edwin Booth.[23]

In this home, Clemens worked on many of his most notable books, including The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and Life on the Mississippi (1883).[24] The success of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer inspired Clemens to renovate the home. In 1881, he had Louis Comfort Tiffany supervise the interior decoration of the house.[25] Twain was also fascinated with new technologies, leading to the installation of an early telephone.[26]

Clemens's invested heavily in the typesetting machine invented by James W. Paige.[24] He also formed the firm Charles L. Webster & Company, which published Twain's writings along with Ulysses S. Grant's memoirs.[27] Its first publication was Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in 1884.[28] The company went bankrupt in 1894, leaving Twain with a large amount of debt.[27] Paige's typesetting machine never functioned properly and was overpowered by competition from the linotype machine developed by Whitlaw Reid.[24] After the losses from these investments as well as several bank panics, the Clemens family moved to Europe in 1891 where the cost of living was more affordable.[22] Clemens began lecturing across the continent to recoup some money for their family.[24]

Architecture and construction

The house was designed by Edward Tuckerman Potter, an architect from New York City.[29] When the house was being built, the Hartford Daily Times noted, "The novelty displayed in the architecture of the building, the oddity of its internal arrangement and the fame of its owner will all conspire to make it a house of note for a long time to come."[22] The cost of the house was paid out of Mrs. Clemens' inheritance.[22]

The home is in the style of Victorian Gothic Revival architecture, including the typical steeply-pitched roof and an asymmetrical bay window layout. Legend says the home was designed to look like a riverboat.[6]

In 1881, an adjoining strip of land was purchased, the grounds re-landscaped, and the home was renovated . The driveway was redrawn, the kitchen rebuilt and its size doubled, and the front hall was enlarged. The family also installed new plumbing and heating and a burglar alarm.[30] After its renovations, the total cost of the home amounted to $70,000, $22,000 were spent on furnishings, and the initial purchase of land cost $31,000.[24]

Post-Twain

Katharine Seymour Day, a grandniece of Harriet Beecher Stowe who had known the Clemens family, saved the Twain House from destruction in 1929. Day founded the Friends of Hartford organization which, after a two-year capital campaign, raised $100,000 to secure a mortgage on the home. Between 1955 and 1974, it was carefully restored.[31] The process of paying off the mortgage, raising money to restore the deteriorating property, and retrieving artifacts, furnishings, and personal possessions took many decades and ended in 1974, just in time for the 100th anniversary of the house.[22] The house earned the David E. Finley Award in 1977 for "exemplary restoration" from the National Trust for Historic Preservation.[32] In 2012, National Geographic named the Twain House one of the ten best historic homes in the world.[33]

Renovation

The house underwent a major renovation starting 1999, including work on the exterior wood and tile, terra cotta brick, and rebuilding the purple slate roofs.[34] Restoration and preservation at the Mark Twain House helped bring the house and grounds back to the years between 1881 and 1891, when the Clemenses most loved the house. The marble floor in the front hallway underwent a historic restoration, and specialists re-stenciled and painted the walls and ceilings and refinishing the woodwork to recover the Tiffany-decorated interiors. Restoration was funded in part by two federal Save America’s Treasures grants totaling $3 million. Scanning computers were also used in the restoration.[35] The home today contains 50,000 artifacts: manuscripts, historic photographs, family furnishings, and Tiffany glass. Many of the original furnishings, including Clemens's ornate Venetian bed, an intricately carved mantel from a Scottish castle, and a billiard table, remain at the house.

With the number of admissions leveling off around 53,000, the house's trustees decided that they must expand or be forced to shrink their operations. They commissioned Robert A. M. Stern, the founder of the Manhattan architectural firm that bears his name and the dean of the Yale School of Architecture, to design a visitor's center that would not draw attention away from the house.[22]

The Education and Visitors Center was built adjacent to the Carriage House where the Clemens family's coachman once lived with his family. The green museum was the first in America to receive a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification.[36] The center is a $16.3 million, 35,000-square-foot (3,300 m2) facility that houses artifacts from the museum's collection that are not shown in the house itself. It contains a lecture hall and classroom facilities.[25] The house received $1 million from the state government to meet expenses related to the construction of the museum and restoration of the house. Since the museum opened in November 2003, attendance has increased by 15%.[37]

In 2000, the house was generating $5 million in tourism from 50,000 visitors.[38] The Aetna foundation gave $500,000 to the campaign.[39] The National Endowment for the Humanities gave $800,000 in challenge grants for teacher development programs, a student writing contest, and an educational website.[40]

In 2011, staff writer Steve Courtney published a book detailing the house's history and renovations. It includes a foreword by Hal Holbrook, a trustee of the house.[41]

Financial problems

After the building of the Visitors Center in 2003, the house became financially unsustainable and launched a campaign to raise awareness and funds. In response, the state government, the governor, United Technologies, and many others contributed.[42] As of 2011, officials of the museum said that it had recovered financially.[43][44][45]

Gallery

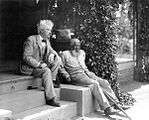

Mark Twain and John T. Lewis, who may have been the inspiration for Jim in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,[46] on the steps of the House.

Mark Twain and John T. Lewis, who may have been the inspiration for Jim in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,[46] on the steps of the House. Exterior, 1970

Exterior, 1970 Porte-cochere from the north, with the Mark Twain carriage house in the background, 1995.

Porte-cochere from the north, with the Mark Twain carriage house in the background, 1995. North elevation, 1995.

North elevation, 1995. Exterior, view of south elevation with partial view of east elevation, 1995.

Exterior, view of south elevation with partial view of east elevation, 1995. Exterior, 2004

Exterior, 2004 Exterior, 2005

Exterior, 2005- View from Southwest, 2006

- View from Northwest, 2006

- View from Northeast, 2006

Exterior, 2007

Exterior, 2007 Exterior, 2009

Exterior, 2009 Exterior and walkway, 2009

Exterior and walkway, 2009- Exterior, 2010

See also

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Connecticut

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Hartford, Connecticut

- North American Reciprocal Museums

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "Mark Twain House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ↑ Courtney, Steve (2011). The Loveliest Home That Ever Was: The Story of the Mark Twain House in Hartford. Dover Publications. p. 29. ISBN 978-0486486345.

- ↑ Kaplan, Justin (1966). Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain. New York: Simon & Shuster. p. 181. ISBN 9780671748074.

- ↑ "Mark Twain Chronology". PBS Learn More website. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- 1 2 Haas, Irvin. Historic Homes of American Authors. Washington, DC: The Preservation Press, 1991. ISBN 0-89133-180-8. p. 31

- ↑ Blanche Higgins Schroer and J. Walter Coleman (November 6, 1974). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Mark Twain House" (PDF). National Park Service.. Accompanying 5 photos, exterior and interior, from c.1965, 1968, 1974 and pre-1970 (2.14 MB)

- ↑ Courtney, Steve (2011). The Loveliest Home That Ever Was: The Story of the Mark Twain House in Hartford. Dover Publications. pp. 123–38. ISBN 978-0486486345.

- ↑ Tedeschi, Bob (19 Sep 2008). "Writers Unite To Keep Twain House Afloat". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- ↑ Larcen, Donna (30 Jan 2009). "Museum in Better Financial Health". The Hartford Courant. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- ↑ Mahoney, Edward (21 Nov 2011). "Twain House Embezzler Sentenced to 3½ years". The Hartford Courant.

- ↑ Goode, Stephen (29 Jun 2012). "Mark Twain House Executive Director Resigning". The Hartford Courant.

- ↑ Goldberg, Carol (28 Feb 2014). "Mark Twain House Comeback". Hartford magazine.

- ↑ Lande, Nathaniel (1991). The 10 Best of Everything, Third Edition: An Ultimate Guide for Travelers. National Geographic Books. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-1426208676.

- 1 2 Corbett, William. Literary New England: A History and Guide. Boston: Faber & Faber, 1993: 11. ISBN 0-571-19816-3

- 1 2 3 Levine, Miriam. A Guide to Writers' Homes in New England. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Apple-wood Press, 1984: 20. ISBN 0-918222-51-6

- ↑ "History of the Institution". The Mark Twain House and Museum. 2004. Archived from the original on 2006-06-02. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ↑ Haas, Irvin. Historic Homes of American Authors. Washington, DC: The Preservation Press, 1991. ISBN 0-89133-180-8. p. 29

- ↑ Paine, Albert Bigelow (1912). "In the Day's Round". Mark Twain: A Biography, Volume III. New York and London: Harper & Brothers. p. 1301. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ↑ Levine, Miriam. A Guide to Writers' Homes in New England. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Apple-wood Press, 1984: 21. ISBN 0-918222-51-6

- ↑ Singer, Stephen (June 4, 2002). "Twain's house a symbol of his success". The Associated Press. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Charles, Eleanor (January 20, 2002). "In the Region/Connecticut; Visitors' Center to Be Built at Mark Twain House". New York Times. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ↑ Davidson, Mashall B. The American Heritage History of the Writers' America. New York: American Heritage Publishing Company, Inc., 1973: 221. ISBN 0-07-015435-X

- 1 2 3 4 5 Corbett, William. Literary New England: A History and Guide. Boston: Faber & Faber, 1993: 12. ISBN 0-571-19816-3

- 1 2 "Remodeling:The Mark Twain House". HGTV. 2006. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ↑ "Mark Twain House". frommers.com. 2006. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- 1 2 "Mark Twain Biography". hannibal.net. 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-04-15. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ↑ Levine, Miriam. A Guide to Writers' Homes in New England. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Apple-wood Press, 1984: 23. ISBN 0-918222-51-6

- ↑ Haas, Irvin. Historic Homes of American Authors. Washington, DC: The Preservation Press, 1991. ISBN 0-89133-180-8. p. 29-30

- ↑ Levine, Miriam. A Guide to Writers' Homes in New England. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Apple-wood Press, 1984: 22. ISBN 0-918222-51-6

- ↑ Lowe, Hilary Iris. Mark Twain's Homes & Literary Tourism. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2012: 112–114. ISBN 978-0-8262-1976-3

- ↑ "Senators Dodd, Lieberman Secure $496,000 for Mark Twain House and Museum". Senate.gov. August 5, 2005. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ↑ Lande, Nathaniel. The 10 Best of Everything, Third Edition: An Ultimate Guide for Travelers (National Geographic the 10 Best of Everything). NY,NY: National Geographic, 1991. ISBN 978-1426208676. p. 60-61

- ↑ Purdy, Stephen L. (July 11, 1999). "The View From/Hartford; A $22 Million Restoration for Mark Twain House". New York Times. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ↑ Kendall, David. "The Mark Twain House". Antiques and the Arts Online. Archived from the original on June 8, 2012. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ↑ Chatalbash, Roy. "Museums Are Going Green - Why Not You?". Antiques and Fine Art. Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ↑ Schain, Dennis (January 31, 2005). "Governor Rell Announces $1 Million for Mark Twain House and Museum". ct.gov. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ↑ Larson, John B. (October 13, 2000). "Larson announces $1 million in funding for Mark Twain House". house.gov. Archived from the original on 2006-06-08. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ↑ Bush, David (2001). "Aetna And The Aetna Foundation Announce $500,000 Gift To The Mark Twain House". Aetna. Archived from the original on 2006-10-16. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ↑ Olson, Elizabeth (December 23, 2005). "Arts, Briefsly; New Humanities Grants". New York Times. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ↑ Courtney, Steve. "The Loveliest Home That Ever Was": The Story of the Mark Twain House in Hartford. Dover Publications, 2011. ISBN 978-0486486345

- ↑ Bulger, Adam (July 19, 2008). "With a Little Help ... The Twain House admits its woes". Hartford Advocate. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ↑ Emami, Gazelle (2012). "Donna Gregor, Mark Twain House Employee, Jailed For Embezzling $1 Million From Museum". huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ↑ Banjo, Shelly (2012). "Former Staffer at Mark Twain Museum Admits Theft - Metropolis - WSJ". blogs.wsj.com. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ↑ Godin, Mary Ellen (2012). "Employee admits embezzling $1 million from Mark Twain House | Reuters". reuters.com. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ↑ "Mark Twain and John T. Lewis". Hartford Courant website. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mark Twain House. |

- Mark Twain House Museum Website

- Library of Congress: Images, drawings and data

- alonzopotter.com: Architect Edward Tuckerman Potter information