Italian general election, 1968

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislative election results map. Light Blue denotes provinces with a Christian Democratic plurality, Red denotes those with a Communist plurality, Gray denotes those with an Autonomist plurality. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

General elections were held in Italy on May 19, 1968.[2] Democrazia Cristiana (DC) remained stable around 38% of the votes. They were marked by a victory of the Communist Party (PCI) passing from 25% of 1963 to c. 30% at the Senate, where it presented jointly with the new Italian Socialist Party of Proletarian Unity (PSIUP), which included members of Socialist Party (PSI) which disagreed the latter's alliance with DC. PSIUP gained c. 4.5% at the Chamber. The Socialist Party and the Democratic Socialist Party (PSDI) presented together as the Unified PSI–PSDI, but gained c. 15%, far less than the sum of what the two parties had obtained separatedly in 1963.

Electoral system

The pure party-list proportional representation had traditionally become the electoral system for the Chamber of Deputies. Italian provinces were united in 32 constituencies, each electing a group of candidates. At constituency level, seats were divided between open lists using the largest remainder method with Imperiali quota. Remaining votes and seats were transferred at national level, where they was divided using the Hare quota, and automatically distributed to best losers into the local lists.

For the Senate, 237 single-seat constituencies were established, even if the assembly had risen to 315 members. The candidates needed a landslide victory of two thirds of votes to be elected, a goal which could be reached only by the German minorities in South Tirol. All remained votes and seats were grouped in party lists and regional constituencies, where a D'Hondt method was used: inside the lists, candidates with the best percentages were elected.

Historical background

Oh 21 August 1964 the historic leader of the Italian Communist Party, Palmiro Togliatti died as a result of cerebral haemorrhage[3] while vacationing with his companion Nilde Iotti in Yalta, then in the Soviet Union. According to some of his collaborators, Togliatti was travelling to the Soviet Union in order to give his support to Leonid Brezhnev's election as Nikita Khrushchev's successor at the head of Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Togliatti was replaced by Luigi Longo, a long-time prominent PCI members; Longo continued Togliatti's line, known as the "Italian road to Socialism", playing down the alliance between the Italian Communist Party and the USSR. He reacted without hostility to the new left movements that sprung up in 1968 and, among the leaders of the PCI, was one of those most disposed to engage with the new activists, although he did not condone their excesses.

Moreover, Francesco De Martino, became the new Secretary of the Italian Socialist Party, after the resignation of Pietro Nenni, due to age.

In 1965, the SIFAR intelligence agency was transformed into the SID following an aborted coup d'état, Piano Solo, which was to give the power to the Carabinieri, then headed by general De Lorenzo.

The difficult equilibrium of Italian society was challenged by a rising left-wing movement, in the wake of 1968 student unrest ("Sessantotto"). This movement was characterized by such heterogeneous events as revolts by jobless farm workers (Avola, Battipaglia 1969), occupations of Universities by students, social unrest in the large Northern factories (1969 autunno caldo, hot autumn). While conservative forces tried to roll back some of the social advances of the 1960s, and part of the military indulged in "sabre rattling" in order to intimidate progressive political forces, numerous left-wing activists became increasingly frustrated at social inequalities, while the myth of guerrilla (Che Guevara, the Uruguayan Tupamaros) and of the Chinese Maoist "cultural revolution" increasingly inspired extreme left-wing violent movements.

Social protests, in which the student movement was particularly active, shook Italy during the 1969 autunno caldo (Hot Autumn), leading to the occupation of the Fiat factory in Turin. In March 1968, clashes occurred at La Sapienza university in Rome, during the "Battle of Valle Giulia." Mario Capanna, associated with the New Left, was one of the figures of the student movement, along with the members of Potere Operaio and Autonomia Operaia such as (Antonio Negri, Oreste Scalzone, Franco Piperno and of Lotta Continua such as Adriano Sofri.

Parties and leaders

Results

The election was a test for the new organization of the socialist area, which was divided between the new revolutionary and Communist-allied Italian Socialist Party of Proletarian Unity and the governmental social-democratic federation between PSI and PSDI. The polls said that the split of the PSIUP in 1964 had not been a purely parliamentary operation, but the reflex of divisions into the leftist electorate. The result shocked the PSI's leadership, causing the sudden sinking of the social-democratic federation, and an alternance of provisional retirements by the government, firstly led by lifetime senator Giovanni Leone and then, through two political crisis, by DC's secretary Mariano Rumor. Unsuccessfully trying to recover its lost leftist electors, the PSI returned to the alliance with the PCI for the regional elections of 1970, so causing another crisis and a new change of premiership, then led by Emilio Colombo, but the government coalition had continuous problems of instability. Influent Giulio Andreotti tried to resurrect the centrist formula in 1972, but he failed, opening the way to the first early election of the republican history.

Chamber of Deputies

| |||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democracy | 12,437,848 | 39.12 | 266 | +6 | |

| Italian Communist Party | 8,551,347 | 26.90 | 177 | +11 | |

| Unified PSI–PSDI | 4,603,192 | 14.48 | 91 | −29 | |

| Italian Liberal Party | 1,850,650 | 5.82 | 31 | −8 | |

| Italian Socialist Party of Proletarian Unity | 1,414,697 | 4.45 | 23 | New | |

| Italian Social Movement | 1,414,036 | 4.45 | 24 | −3 | |

| Italian Republican Party | 626,533 | 1.97 | 9 | +3 | |

| Italian Democratic Party of Monarchist Unity | 414,507 | 1.30 | 6 | −2 | |

| South Tyrolean People's Party | 152,991 | 0.48 | 3 | ±0 | |

| Social Democracy | 100,212 | 0.32 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Democratic Union for the New Republic | 63,402 | 0.20 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Autonomous Party of Pensioners of Italy | 41,416 | 0.13 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Valdostan Union | 31,557 | 0.10 | 0 | −1 | |

| Others | 87,674 | 0.28 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Invalid/blank votes | 1,211,216 | – | – | – | |

| Total | 33,001,644 | 100 | 630 | ±0 | |

| Registered voters/turnout | 35,566,493 | 92.79 | – | – | |

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | |||||

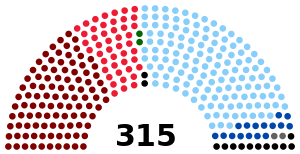

Senate of the Republic

| |||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democracy | 10,972,114 | 38.34 | 135 | +6 | |

| PCI–PSIUP | 8,585,601 | 30.00 | 101 | +17 | |

| Unified PSI–PSDI | 4,354,906 | 15.22 | 46 | −12 | |

| Italian Liberal Party | 1,943,795 | 6.79 | 16 | −2 | |

| Italian Social Movement | 1,304,847 | 4.56 | 11 | −3 | |

| Italian Republican Party | 622,388 | 2.17 | 2 | +2 | |

| Italian Democratic Party of Monarchist Unity | 312,702 | 1.09 | 2 | ±0 | |

| MSI–PDIUM | 292,349 | 1.02 | 0 | −1 | |

| South Tyrolean People's Party | 131,071 | 0.46 | 2 | ±0 | |

| Social Democracy | 36,073 | 0.13 | 0 | New | |

| Valdostan Union | 28,414 | 0.10 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Others | 31,761 | 0.11 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Invalid/blank votes | 2,740,176 | – | – | – | |

| Total | 30,252,921 | 100 | 315 | ±0 | |

| Registered voters/turnout | 32,517,638 | 93.04 | – | – | |

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | |||||

References

- ↑ In the coalition Unified PSI–PSDI, with the Italian Democratic Socialist Party.

- ↑ Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p1048 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- ↑ Agosti, Aldo. Palmiro Togliatti: A Biography. London: I. B. Tauris. pp. 291–292. ISBN 1-84511-726-3. Retrieved 6 July 2015.