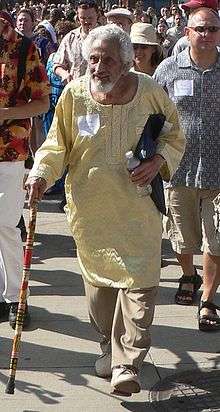

Halim El-Dabh

Halim Abdul Messieh El-Dabh (Arabic: حليم عبد المسيح الضبع, Ḥalīm ʻAbd al-Masīḥ al-Ḍabʻ; born March 4, 1921) is an Egyptian American composer, performer, ethnomusicologist, and educator, who has had a career spanning six decades. He is particularly known as an early pioneer of electronic music.[1] In 1944 he composed one of the earliest known works of tape music,[2] or musique concrète. From the late 1950s to early 1960s he produced influential work at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center [3]

Early life

El-Dabh was born and grew up in Sakakini, Cairo, Egypt, a member of a large and affluent Coptic family that had earlier emigrated from Abutig in the Upper Egyptian province of Asyut. The family name means "the hyena" and is not uncommon in Egypt. In 1932 the family relocated to the Cairo suburb of Heliopolis. Following his father's profession of agriculture, he graduated from Fuad I University (now Cairo University) in 1945 with a degree in agricultural engineering, while also studying, performing, and composing music on an informal basis. Although his main income was derived from his job as an agricultural consultant, he achieved recognition in Egypt from the mid- to late 1940s for his innovative compositions and piano technique.

Early electronic music in Cairo

It was while he was still a student in Cairo that he began his experiments in electronic music. El-Dabh first conducted experiments in sound manipulation with wire recorders there in the early 1940s. By 1944, he had composed one of the earliest known works of tape music [2] or musique concrète, called The Expression of Zaar, pre-dating Pierre Schaeffer's work by four years.[1] Having borrowed a wire recorder from the offices of Middle East Radio, El-Dabh took it to the streets to capture outside sounds, specifically an ancient zaar ceremony. Intrigued by the possibilities of manipulating recorded sound for musical purposes, he believed it could open up the raw audio content of the zaar ceremony to further investigation into “the inner sound” contained within.[1]

According to El-Dabh, “I just started playing around with the equipment at the station, including reverberation, echo chambers, voltage controls, and a re-recording room that had movable walls to create different kinds and amounts of reverb.” He further explains: "I concentrated on those high tones that reverberated and had different beats and clashes, and started eliminating the fundamental tones, isolating the high overtones so that in the finished recording, the voices are not really recognizable any more, only the high overtones, with their beats and clashes, may be heard." He thus discovered the potential of sound recordings as raw material to compose music. His final 20-25 minute piece was recorded onto magnetic tape and called The Expression of Zaar, which was publicly presented in 1944 at an art gallery event in Cairo.[4] Following a well received 1949 performance at the All Saints Cathedral in Cairo, he was invited by an official of the U.S. embassy to study in the United States.

Move to the United States

Coming to the United States in 1950 on a Fulbright fellowship (as expanded to include Egypt via the Smith-Mundt Act of 1948), El-Dabh studied composition with John Donald Robb and Ernst Krenek at the University of New Mexico; with Francis Judd Cooke at the New England Conservatory of Music; with Aaron Copland, Irving Fine, and Luigi Dallapiccola at the Berkshire Music Center; and with Irving Fine at Brandeis University. El-Dabh and his family rented a house in Demarest, New Jersey before buying a home in Cresskill, New Jersey where they lived for some time.[5]

El-Dabh soon became a part of the New York new music scene of the 1950s, alongside such like-minded composers as Henry Cowell, John Cage, Edgard Varèse, Alan Hovhaness, and Peggy Glanville-Hicks. He obtained U.S. citizenship in 1961.

Among El-Dabh's works are four ballet scores for Martha Graham, including her masterpiece Clytemnestra (1958), as well as One More Gaudy Night (1961), A Look at Lightning (1962), and Lucifer (1975). Many of his compositions draw on Ancient Egyptian themes or texts, and one such work is his orchestral/choral score for the Sound and Light show at the site of the Pyramids at Giza, which has been performed there each evening since 1961.

El-Dabh's primary instruments are the piano and darabukha (an Egyptian goblet- or vase-shaped hand drum with a body made of fire-hardened clay), and consequently many of his works are composed for these instruments. In 1958 he performed the demanding solo part in the New York City premiere of his Fantasia-Tahmeel for darabukha and string orchestra (probably the first orchestral work to feature this instrument), with an orchestra under the direction of Leopold Stokowski. In 1959 he composed several works for an ensemble of percussion instruments from India, for the New York Percussion Trio.

Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center

After having become acquainted with Otto Luening and Vladimir Ussachevsky by 1955, by which time El-Dabh he had been experimenting with electronic music for ten years, they later invited him to work at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in 1959 as one of the first outside composers there,[6] where he would become one of the most influential composers associated with the early years of the studio.[7] El-Dabh's unique approach to combining spoken words, singing and percussion sounds with electronic signals and processing contributed significantly to the development of early electroacoustic techniques at the center.[6] Some of his compositions also made extensive use of Columbia-Princeton's RCA Synthesizer, an early programmable synthesizer.[8] He worked there sporadically until 1961,[7] creating various tape works, including at least two in collaboration with Luening. Other composers he had become acquainted with at Columbia-Princeton include John Cage, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein.[9]

El-Dabh produced eight electronic pieces in 1959 alone, including his multi-part electronic musical drama Leiyla and the Poet,[6] which is considered a classic of the genre and was later released in 1964 on the LP record Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center.[10] His musical style was a contrast to the more mathematical compositions of Milton Babbitt and other serial composers working at the center, with El-Dabh's interest in ethnomusicology and the fusion of folk music with electronic sounds making his work stand out for its originality. According to El-Dabh: “The creative process comes from interacting with the material. When you are open to ideas and thoughts the music will come to you.”[6] In contrast to his peers (such as Otto Luening, John Cage, and La Monte Young) who sounded, according to The Stranger, more like "math equations (artists out to prove a point) than actual music," El-Dabh's experimental electronic music were "more shapely and rhythmic constructions" that incorporated traditional stringed and percussion sounds, inspired by folk music traditions (including the Egyptian and Native American traditions).[9]

Making full use of all ten Ampex tape recorders available to him at Columbia, his approach to composing electronic music was for immersion, with his seamless blending of vocals, electronic tones, tape manipulation such as speed transposition, and music looping, giving Leiyla and the Poet an "unearthly quality" that made it influential among many composers at the time. The number of musicians who have acknowledged the importance of his recordings to their work range from Neil Rolnick, Charles Amirkhanian and Alice Shields to rock musicians such as Frank Zappa and The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band.[11] The "organic textures and raw energy" of Leiyla and the Poet in particular inspired many early electronic music composers.[12] Leiyla and the Poet also featured a "sonorous, echoing voice, sonar signals, distorted ouds, percussion that sounds like metal," and "shadowy, shifting dream music." Other works he composed there include the 1959 pieces "Meditation in White Sound", "Alcibiadis' Monologue to Socrates", and the chimey, rhythmic "Electronics and the Word", as well as the 1961 piece "Venice" which is reminiscent of Steve Reich's field recording experiments in the mid-1960s. El-Dabh also helped introduce an "Egyptian folk sensibility" to Western avant-garde music.[9] A definitive collection of El-Dabh's electronic work was restored by Mike Hovancsek. This CD, titled Crossing into the Electric-Magnetic,[13] includes a collaboration with Otto Luening, environmental recordings, and wire recordings that the liner notes cite as "arguably the earliest example of electronic music."

Later life and career

Like Béla Bartók before him, El-Dabh has also conducted numerous research trips in various nations, recording and otherwise documenting traditional musics and using the results to enrich his compositions and teaching. From 1959 to 1964 the most significant of these trips included investigations of the musics across the length and breadth of Egypt and Ethiopia, with later fieldwork being conducted in Mali, Senegal, Niger, Guinea, Zaire, Brazil, and several other nations. During the 1970s, El-Dabh served as a consultant to the Smithsonian Institution and conducted research on the traditional puppetry of Egypt and Guinea.

El-Dabh served as associate professor of music at Haile Selassie I University (now Addis Ababa University) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, professor of African studies at Howard University (1966–69), and professor of music and Pan-African studies at Kent State University (1969–91); he continued to teach courses in African studies there on a part-time basis until 2012. Among the awards and honors he has received are two Fulbright awards (1950 and 1967), three MacDowell Colony residencies (1954, 1956, and 1957), two Guggenheim Fellowships (1959–60 and 1961–62), two Rockefeller Foundation fellowships (1961 and 2001), a Meet-the-Composer grant (1999), an Ohio Arts Council grant (2000), and two honorary doctorates (Kent State University, 2001; and New England Conservatory, 2007).

El-Dabh is probably the best known composer of Arabic descent and his works are highly regarded in Egypt, where he is considered the foremost living composer among that nation's "second generation" of contemporary composers. He was invited back to his homeland in April 2002 for a festival of his music at the newly constructed Bibliotheca Alexandrina in Alexandria, Egypt; most of the compositions presented were heard by the Egyptian public for the first time.

Many of El-Dabh's scores are published by the C. F. Peters Corporation and his music has been recorded by the Folkways and Columbia labels. Previously unpublished works are also being produced by Deborah El-Dabh of Halim El-Dabh Music, LLC. The first biography of the composer, The Musical World of Halim El-Dabh by Denise A. Seachrist, was published by the Kent State University Press in 2003.

He has been a frequent performer and speaker at both the WinterStar Symposium and the Starwood Festival,[14] where he performed with lifelong friend and master drummer Babatunde Olatunji in 1997,[15] and where El-Dabh's concert of traditional sacred African music was recorded in 2002.[16] In 2003 he was part of a three-day tribute to the late Olatunji called the SpiritDrum Festival,[17] with Muruga Booker, Badal Roy, Sikiru Adepoju, Jeff Rosenbaum, and Jim Donovan of Rusted Root. In 2005 he performed and ran workshops at Unyazi 2005 in Johannesburg, which was the first electronic music symposium and festival to be hosted in Africa.

He is a National Patron of Delta Omicron, an international professional music fraternity.[18]

He lives with his wife in Kent, Ohio, and has three grown children.

Discography

Audio

- 1944 – The Expression of Zaar

- 1957 – Sounds of New Music. New York: Folkways.

- 1959 – Leiyla and the Poet

- 1961 – Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. New York: Columbia Masterworks.

- 1989 – The Self in Transformation: A Panel Discussion. Cassette tape: Features Donald Michael Kraig, Jeff Rosenbaum, Joseph Rothenberg, and Robert Anton Wilson. ACE.

- 2000 – Gilbertson, Nancy. Mediterranean Magic. Moravia, New York: Nancy Cody Gilbertson. Includes Mekta' in the Art of Kita', Book 3.

- 2000 – Olatunji Live at Starwood – Babatunde Olatunji & Drums of Passion (guest Halim El-Dabh). CD: Recorded at the 17th Starwood Festival in July 1997. ACE

- 2001 – El-Dabh, Halim. Crossing Into the Electric Magnetic. Lakewood, Ohio: Without Fear.

- 2002 – Halim El-Dabh Live at Starwood – Halim El-Dabh (With: Seeds of Time) CD: Recorded at the 22nd Starwood Festival in July 2002. ACE

- 2002 – El-Dabh, Halim Blue Sky Transmission: A Tibetan Book of the Dead (original cast recording) Cleveland Public Theatre, Halim El-Dabh, and Raymond Bobgan

- 2006 – Fan, Joel. World Keys. San Francisco, California: Reference Recordings. Includes "Sayera" from Mekta' in the Art of Kita', Book 3.

- 2016 - El-Dabh, Halim; Ron Slabe. Sanza Time.

Films

- 1960 – Yuriko: Creation of a Dance. Features a rehearsal of The Ghost, with score by El-Dabh

- 1967 – Herostratus. Directed by Don Levy. One scene features audio of El-Dabh's Spectrum no. 1: Symphonies in Sonic Vibration

- 2000 – Olatunji Live at Starwood – Babatunde Olatunji & Drums of Passion (guest Halim El-Dabh). DVD: Filmed at the 17th Starwood Festival in July 1997. ACE.

- 2002 – Halim El-Dabh Live at Starwood – Halim El-Dabh (With: Seeds of Time) DVD: Filmed at the 22nd Starwood Festival in July 2002. ACE.

Notes

- 1 2 3 Holmes, Thom (2008). "Early Synthesizers and Experimenters". Electronic and experimental music: technology, music, and culture (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 156. ISBN 0-415-95781-8. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- 1 2 "The Wire, Volumes 275-280", The Wire, p. 24, 2007, retrieved 2011-06-05

- ↑ Holmes, Thom (2008). "Early Synthesizers and Experimenters". Electronic and experimental music: technology, music, and culture (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. pp. 153–4 & 156–7. ISBN 0-415-95781-8. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ Holmes, Thom (2008). "Early Synthesizers and Experimenters". Electronic and experimental music: technology, music, and culture (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. pp. 156–7. ISBN 0-415-95781-8. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ Seachrist, Denise A. "The Musical World of Halim El-Dabh", pp. 54 and 95, Kent State University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-87338-752-X. Accessed July 8, 2011. From page 54: "Elated that his wife had finally agreed to join him in New York, El-Dabh sought more suitable accommodations for his family and located a house for rent in Demarest, New Jersey." From page 95: "Mary and the girls were delighted to return to the United States, and when El-Dabh purchased a home in Cresskill, New Jersey, Mary was optimistic that her peripatetic husband was finally ready to settle down."

- 1 2 3 4 Holmes, Thom (2008). "Early Synthesizers and Experimenters". Electronic and experimental music: technology, music, and culture (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 157. ISBN 0-415-95781-8. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- 1 2 Holmes, Thom (2008). "Early Synthesizers and Experimenters". Electronic and experimental music: technology, music, and culture (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 153. ISBN 0-415-95781-8. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ "The RCA Synthesizer & Its Synthesis", Contemporary Keyboard, GPI Publications, 6, p. 64, 1980, retrieved 2011-06-05

- 1 2 3 Feit, Josh (December 2001). "Have an Electronic Arabic Christmas: Halim El-Dabh, 'Crossing into the Electric Magnetic'". The Stranger. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ↑ Holmes, Thom (2008). "Early Synthesizers and Experimenters". Electronic and experimental music: technology, music, and culture (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. pp. 153 & 438. ISBN 0-415-95781-8. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ Holmes, Thom (2008). "Early Synthesizers and Experimenters". Electronic and experimental music: technology, music, and culture (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. pp. 153–4. ISBN 0-415-95781-8. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ Holmes, Thom (2008). "Pioneering Works of Electronic Music". Electronic and experimental music: technology, music, and culture (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 430. ISBN 0-415-95781-8. Retrieved 2011-06-26.

- ↑ Holmes, Thom (2008). "Early Synthesizers and Experimenters". Electronic and experimental music: technology, music, and culture (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. pp. 157 & 439. ISBN 0-415-95781-8. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ ACE : Starwood Speaker Roster

- ↑ Starwood Guests

- ↑ ACE presents: Starwood 2002 – Program

- ↑ Spirit Drum: brought to you by ACE

- ↑ Delta Omicron

References

- Bibliographic Guide to Dance by the New York Public Library Dance Collection.

- Freedman, Russell. Martha Graham: A Dancer's Life.

- Gilbert, Chase. America’s Music, From the Pilgrims to the Present.

- Gill, Michael. Circle of Ash. 7 July 2005. Free Times article referencing Starwood Festival appearance.

- Hartsock, Ralph and Carl John Rahkonen. Vladimir Ussachevsky: A Bio-Bibliography.

- Holmes, Thomas B. Electronic and Experimental Music: Pioneers in Technology and Composition.

- Horne, Aaron. Brass Music of Black Composers: A Bibliography.

- _____. Woodwind Music of Black Composers.

- Howard, John Tasker. Our American Music: A Comprehensive History from 1620 to the Present.

- Landis, Beth and Eunice Boardman. Exploring Music.

- Seachrist, Denise A. The Musical World of Halim El-Dabh. Includes compact disc. Kent OH, USA: Kent State University Press, 2003.

- Shelemay, Kay Kaufman and Peter Jeffery. Ethiopian Christian Liturgical Chant.

- Smith, Gordon Ernest. Istvan Anhalt: Pathways and Memory. 1950.

- South, Aloha P. Guide to Non-Federal Archives and Manuscripts in the United States Relating to Africa.

Further References

- Gluck, Bob. “… ‘like a sculptor, taking chunks of sound and chiselling them into something beautiful’: Interview with Egyptian composer Halim El Dabh.” eContact! 15.2 — TES 2012: Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium / Symposium électroacoustique de Toronto (April 2013). Montréal: CEC.

- Soundcheck. “The Musical World of Halim El-Dabh.” Interview on WNYC’s Soundcheck program, 13 June 2003.

- Premiere performance of The Dog Done Gone Deaf (2007), from CBC Radio Two. (dead link as of 9 Feb. 2014)