Gobindapur, Kolkata

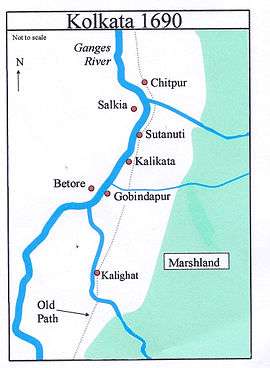

Gobindapur (Bengali: গোবিন্দপুর) was one of the three villages which were merged to form the city of Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) in India. The other two villages were Kalikata and Sutanuti. Job Charnock, an administrator with the British East India Company is traditionally credited with the honour of founding the city. While Kalikata and Sutanuti lost their identity as the city grew, Gobindapur was demolished to make room for the construction of new Fort William.

The foundations

When the Portuguese first started to frequent Bengal, around the year 1530, the two great centres of trade were Chittagong, which the Portuguese called Porto Grande or Great Haven, in the east and Satgaon, which the Portuguese called Porto Piqueno or Little Haven in the west. Tolly’s Nallah or Adi Ganga was then the outlet to the sea and ocean-going ships came up to around where Garden Reach is now, then the anchoring place for ships. Only country boats operated further up the river.[1] Possibly the Saraswati river was another watery life line. It started drying up from the middle of the sixteenth century. The Portuguese built a new port at Hugli in 1580.[2]

Towards the beginning of 16th century, there was a person name Gobindasharan Dutta Chaudhury,[3] who belonged to a kayastha zamindar of Andul Dutta Chaudhury Family was returning by boat from a pilgrimage. He dreamt of goddess Kali asking him to dig the barren land on the bank. He did so and discovered enormous qualities of wealth hidden underground. He stayed back and founded the place. It is said that the name of the place Gobindapur was named after him.

There is another story regarding the foundation and naming of the village.Towards the end of the sixteenth century, the Indian merchant-princes of Port Piqueno were forced to seek another market for their trade. Most of them settled down in Hugli but four families of Basaks and one of Sheths, determined to profit by the growing prosperity of Betor, founded the village of Gobindapur, on the east bank of the river.[1] Gobindaji was the family deity of the Sheths and Basaks, and so they named the village Gobindapur.[4]

Beyond the purely European buildings lying around the Fort where four villages of mud and bamboo, all of which were included in the zemindary limits of the original settlement. These villages were the original three with the addition of Chowringhee, which was in 1717 a hamlet of isolated hovels, surrounded by water-logged paddy fields and bamboo-groves and separated from Govindpore by a tiger-haunted jungle where expands the grassy level of the maidan. The Esplanade was a jungle not yet cleared, interspersed with a few huts and small plots of grazing and arable lands. Beyond the Chitpore Road which formed the eastern boundary of the settlement, lay more pools, swamps and rice fields, dotted here and there with the struggling huts of fishermen, falconers, wood-cutters, weavers and cultivators.[5]

In 1596, the place is mentioned as a district of the Sirkar (or government) of Satgaon, in the book Ain-e-Akbari by Abul Fazal, the prime minister of Akbar. As traders, the Portuguese were succeeded by the Dutch and finally the British.[1]

English arrival

Job Charnock favoured Sutanuti as a settlement because of the security of the location. It was protected by the river on the west and by impassable marshes on the south and the east. Only the north-east had to be guarded.[6]

The three villages were part of the khas mahal or imperial jagir (an estate belonging to the Mughal emperor himself), whose zemindari rights were held by the Sabarna Roy Choudhury family of Barisha. On 10 November 1698, Job Charnock’s successor and son-in-law, Charles Eyere, acquired the land holding rights for the three villages from the Sabarna Roychoudhuris. The company paid regular rent to the Mughals for these villages till 1757.[7] Within a short period Kolkata grew considerably.

New Fort William

Siraj ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, was alarmed by the growing prosperity and enhanced fortifications of Kolkata. In 1756, he decided to attack Kolkata and captured it. Gobindapur was fired by the English themselves. The English evacuees set up temporary quarters at Falta, some 40 miles downstream. What followed was a series of skirmishes finally leading to the Battle of Plassey on 23 June 1757 and the establishment of British power in Bengal.[8]

On the riverside to the south of the settlement was the village of Govindpore, founded two centuries earlier by the Setts and Bysacks, the Hindu Fathers of Calcutta: and surrounding it was a thick tiger-infested jungle that could be easily cut down. The whole colony, with their tutelary deity Gobindjee, migrated to the north of Calcutta, and liberal compensation in money and in grants of lands were made to them for their dispossession.[9]

H.E.A.Cotton

One of the first things that the English embarked upon on their return to Kolkata was the construction of new Fort William. It commenced in 1758 and completed in 1773. The site chosen was in the heart of ‘populous flourishing’ village of Gobindapur. A portion of the ‘restitution money’ was spent in compensating the inhabitants who were given lands in other parts of the town notably in Taltala, Kumortuli and Shobhabazar.[10]

References

- 1 2 3 Cotton, H.E.A., Calcutta Old and New, 1909/1980, pp. 1-4, General Printers and Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- ↑ Patree, Purnendu, Purano Kolkatar Kathachitra, (a book on History of Calcutta), (Bengali), first published 1979, 1995 edition, p.71, Dey’s Publishing, ISBN 81-7079-751-9.

- ↑ "05 Hatkhola.pdf". Retrieved 2016-07-04.

- ↑ Patree, Purnendu, pp. 160-1

- ↑ Cotton, H.E.A., p. 19.

- ↑ Sengupta, Nitish, "History of the Bengali-speaking People", 2001/2002, pp.123-124, UBS Publishers’ Distributors Pvt. Ltd., ISBN 81-7476-355-4

- ↑ Nair, P.Thankappan, The Growth and Development of Old Calcutta, in Calcutta, the Living City, Vol I, pp. 10-12, edited by Sukanta Chaudhuri, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-563696-1

- ↑ Sinha, Pradip, Siraj’s Calcutta, in Calcutta, the Living City, Vol I, pp. 8-9

- ↑ Cotton, H.E.A., p. 688

- ↑ Cotton, H.E.A., p. 72.