Whitley Castle

| ||||

| Part of a series on the | ||||

| Military of ancient Rome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural history | ||||

|

||||

| Campaign history | ||||

| Technological history | ||||

|

||||

| Political history | ||||

|

|

||||

| Strategy and tactics | ||||

|

||||

|

| ||||

Whitley Castle is a large and uniquely shaped Roman fort (Latin: castra) north-west of Alston, Cumbria, England that was known to the Romans as Epiacum. The fort was built early in the 2nd century and at least partly demolished and rebuilt around AD 200.

Whereas Roman forts are normally "playing-card shaped" (rectangular with rounded corners), Whitley Castle is lozenge-shaped to fit the available site. In addition, it has the most complex defensive earthworks of any known fort in the Roman Empire, with multiple banks and ditches outside the usual stone ramparts. The fort appears to have been sited to control and protect lead mining in the area as well as to support the border defences of Hadrian's Wall.

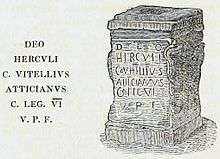

The fort was surveyed by the geologist Thomas Sopwith in the 19th century and the historian R.G. Collingwood in the 20th, with a geophysics survey in the 21st, but it has not been fully excavated. Among finds at the fort are altars with inscriptions to Hercules by the 6th Legion of the Roman army (normally stationed at York) and to Apollo by the fort's garrison of auxiliaries, the 2nd Cohort of Nervians. Other finds include a midden containing shoes; coins, fragments of Samian pottery, beads, nails, and a bronze handle shaped like a dolphin.

Situation

Whitley Castle is about 1,000 ft (300 m) above sea level in the Pennine hills on the border of Cumbria and Northumberland. It lies to the west of the modern A689 road beside the Pennine Way long-distance footpath.[1] During the Roman era, Epiacum was situated about 15 mi (24 km) south of Hadrian's Wall and 20 mi (32 km) north of the main road which ran between Luguvalium (Carlisle) in the northwest and Eboracum (York) in the southeast.[2] The Maiden Way road connected it to Magnae (Carvoran) on the Wall and Bravoniacum (Kirkby Thore) on the Carlisle–York road.

Whitley Castle is one of the most isolated Roman sites in Britain, which may help to explain both why it remains largely unexcavated as of 2012 and why so much of it has survived.[3] The site is a lozenge-shaped spur of high ground on Castle Nook hill farm[4] under permanent pasture. The remains lie under the grass, and are most clearly seen in aerial photographs.[5] The Roman fort itself covers about 4 acres (1.6 ha); outside it is a system of concentric defensive ditches.[6]

The fort may have been sited to exert control over the area near Alston and its lead mines, as well as to provide support for Hadrian's Wall.[6]

Roman fort

Epiacum was built early in the 2nd century. It was at least partly demolished and rebuilt around AD200; the destruction coincides with an uprising of the northern tribes in 196.[7] The fort was modified or wholly rebuilt about the year 300. It appears to have been preceded by an Iron Age fort, followed by a Roman camp before the permanent fort was constructed.[2][6]

Epiacum is in some ways a typical Roman fort: inside the wall are straight roads which cross, a headquarters building (the Praetorium), the commandant's house, a set of barrack blocks for the cohort of auxiliary soldiers, and granaries to store food. Also as usual, there is a bath house and a temple (dedicated by the auxiliaries to the Emperor Caracalla) outside the wall.[6] There is an altar to Mithras and another, as already mentioned, to Hercules.[2]

Epiacum, however, has two unique features. Firstly, the fort's military engineers modified the usual rectangular plan to suit the available site: it is distorted into a lozenge or parallelogram; the internal features of the fort are similarly distorted. Six barracks were however fitted in behind the headquarters building (Principia), and four in front of it, in a limited area of 1.25 hectares (3.1 acres).[3] Secondly, the wall is surrounded by four steep defensive ditches and banks around the hill spur, and seven such ramparts across the uphill side of the spur.[2][6] These constitute the most complex defensive earthworks of any known Roman fort, with multiple banks and ditches outside the usual stone ramparts.[6]

Inscriptions on some of the altars found at Epiacum provide evidence of the Roman army units garrisoning the fort. One of these is inscribed "DEO HERCVLI C VITELLIVS ATTICIANVS > LEG VI V P F" ("To the god Hercules, Gaius Vitellius Atticianus, Centurion of the Legio VI Victrix, Loyal and Faithful, [erected this].")[8] This was a regular army legion based at York.[2][6][9]

Another altar is inscribed "DEO APOLLINI G...IVS ... ...COH II NER ..." ("To the god Apollo, Gaius Julius Marcius, [commander] of the 2nd Cohort of Nervians, [fulfilled his vow]."). This and two other inscriptions also naming the 2nd Nervians, auxiliaries from the lower Rhine, date to 213-221 AD.[10] The altar was in a socket of a big stone slab supported by four columns, each topped by a coin; one of these was dated to 141-161 AD.[11]

Archaeology

Little archaeological research has taken place at Whitley Castle.[13] In 1810, the Revd. John Hodgson excavated the bath house, in the north-east corner of Epiacum.[14] In 1825 several leather shoes were recovered from a Roman rubbish tip when a Mr Henderson was cutting a drainage ditch.[13][15] The geologist Thomas Sopwith surveyed the fort, describing it, its baths and the midden (waste heap) in 1833 as follows:[16]

Still further north [of the multiple ditches] are the remains of the Hypocausta or baths — the supposed cemetery of the station — and, what is rather a variety in antiquarian researches, the perfect remains of a Roman middenstead, which, strange as it may appear, has furnished many loads of excellent manure to the neighbouring fields, and been hitherto the productive mine of several interesting curiosities.— Thomas Sopwith

The fort was surveyed and described by R.G. Collingwood in his Archaeology of Roman Britain, 1930, where he noted the fort's uniquely skewed shape and extraordinary set of defensive ramparts on the northern, uphill side.[17] Pottery excavated in the 1950s suggested that the fort was constructed in 122 AD, at the same time as Hadrian's Wall.[13] A survey in 2007–8 by English Heritage[3] showed a large Roman civilian settlement or vicus to the north and west of the fort. Artefacts found include coins, pottery, glass, objects made of jet, and inscribed stones.[18] In 2012, the University of Durham carried out a geophysics survey as part of an English Heritage project.[19] In the absence of a full excavation, archaeologists have exploited the diggings of moles to uncover Roman artefacts by sifting earth thrown up by the animals in their molehills. Finds include fragments of terra sigillata (Samian ware, Roman table pottery); rim fragments of serving bowls and earthenware pots; a bead made of jet; some iron nails;[4] and a bronze dolphin from the bath house, most likely the handle of an instrument like a strigil or razor.[20]

Name

The Roman name for the fort, Epiacum, is given in Ptolemy's Geography as the first town in the area of the Brigantes tribe of northeastern England. The name probably means "the property, or estate of Eppius. 'Eppius' is a Romanised Celtic or British name, and he may have been a local leader of the tribe of Brigantes."[21][22][lower-alpha 1]

Protection

The site is on the privately owned Castle Nook Farm, and is a Scheduled Ancient Monument. In 2012 the not-for-profit company Epiacum Heritage Ltd. secured a £49,200 Heritage Lottery Fund grant[4] to develop a programme of events for the fort to include a website, guided tours for the public, archaeology survey days for volunteers and educational events for schools.[20]

Notes

- ↑ The suffix -acum is a widespread placename element in Brittany, the southwest of France and other regions including Wales, Cornwall and Ireland. It appears to be Gallic or Celtic (not Latin) in origin, and it often but not always indicates the land belonging to a named person. Its distribution and meaning are discussed in detail on the French Wikipedia at Suffixe -acum.

References

- ↑ Dunford, Dave (31 August 2005). "NY6948: Whitley Castle Roman Fort". Geograph. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Archaeological Field Survey and Investigation". Whitley Castle Roman Fort Cumbria. English Heritage. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 Went, Dave; Ainsworth, Stewart (2009). "Whitley Castle, Tynedale, Northumberland: An Archaeological Investigation of the Roman Fort and its Setting" (PDF). English Heritage. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 Tully, Paul (21 April 2012). "Roman artefacts at Epiacum churned up by moles". The Journal. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ↑ "Epiacum Roman fort in Cumbria to open to visitors". BBC. 22 May 2012. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Pastscape". Whitley Castle Roman Fort. English Heritage. 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ↑ Robertson, 2007. p10

- ↑ Robertson, 2007. p22

- ↑ Nitze, William A. (August 1941). "Bedier's Epic Theory and the "Arthuriana" of Nennius". Modern Philology. 39 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1086/388502. JSTOR 434162.

- ↑ Collingwood, R.G. & Wright, R.P. (1965). The Roman Inscriptions of Britain. Oxford. pp. 1198–1199.

- ↑ Robertson, 2007. pp23-24

- ↑ Bruce, John Collingwood (1853). The Roman Wall (2nd ed.).

- 1 2 3 North Pennines AONB/English Heritage leaflet 'Whitley Castle' ref NMR 20677/026, 2013

- ↑ Robertson, 2007. pp16-17

- ↑ Robertson, 2007. p19

- ↑ Sopwith, Thomas (1833). An account of the mining districts of Alston Moor, Weardale and Teesdale in Cumberland and Durham : comprising descriptive sketches of the scenery, antiquities, geology, and mining operations, in the upper dales of the rivers Tyne, Wear, and Tees. Alnwick: W. Davison. pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Collingwood, R.G. (1930). The Archaeology of Roman Britain. Methuen. p. 45.

- ↑ "Alston Moor, Cumbria". Alston's Hidden Gem. Cybermoor.org. 25 April 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ↑ "Whitley Castle Geophysics Survey". Archaeology Data Service. 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- 1 2 "History / The Romans". Epiacum Roman Fort. Epiacum Heritage. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ↑ Robertson, 2007. p9

- ↑ Esmonde Cleary, A., R. Warner, R. Talbert, T. Elliott, S. Gillies, S. Vanderbilt. "Places: 89176 (Epiakon (Epiacum))". Pleiades. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

Sources

- Robertson, Alastair F. (2007). Whitley Castle; Epiacum: A Roman Fort near Alston in Cumbria (3rd ed.). Hundy. ISBN 978-0-954-73394-0.

External links

- Whitley Castle Roman Fort

- Cybermoor: Alston Moor, Cumbria

- Geograph: Whitley Castle Roman Fort (photographs)

- Roman Britain: Epiacum

- Epiacum Heritage (official website)

Coordinates: 54°49′55″N 2°28′35″W / 54.83203°N 2.47630°W