Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes

| Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes (Obergermanisch-Raetischer Limes) | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

|

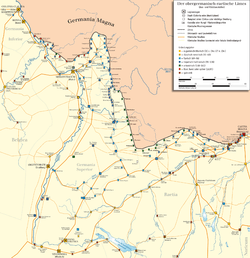

Map of the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes | |

| Location | Germany |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | (ii)(iii)(iv) |

| UNESCO region | Europe |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2005 (29th Session) |

| Extensions | 2008 |

The Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes (German: Obergermanisch-Raetische Limes), or ORL, is a 550-kilometre-long section of the former external frontier of the Roman Empire between the rivers Rhine and Danube. It runs from Rheinbrohl to Eining on the Danube. The Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes is an archaeological site and, since 2005, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Together with the Lower Germanic Limes it forms part of the Limes Germanicus.

Terminology

The term limes (plural: limites) originally meant "border path" or "swathe" in Latin. In Germany, "Limes" usually refers to the Rhaetian Limes and Upper Germanic Limes, collectively referred to as the Limes Germanicus. Both sections of limes are named after the adjacent Roman provinces of Raetia (Rhaetia) and Germania Superior (Upper Germania).

In the Roman limites we have, for the first time in history, clearly defined territorial borders of a sovereign state that were visible on the ground to friend and foe alike. Most of the Upper German-Rhaetian Limes did not follow rivers or mountain ranges, which would have formed natural boundaries for the Roman Empire. It includes the longest land border in the European section of the limes, interrupted for only a few kilometres, by a section that follows the River Main between Großkrotzenburg and Miltenberg. By contrast, elsewhere in Europe, the limes is largely defined by the rivers Rhine (Lower Germanic Limes) and Danube (Danube Limes).

Function

The function of the Roman military frontiers has been increasingly discussed for some time. The latest research tends to view at least the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes not as a primarily military demarcation line, but rather a monitored economic boundary for the non-Roman lands. The limes, it is argued, was not really suitable for fending off systematic external attacks. Thanks to a skillful economic policy, the Roman Empire extended its influence far to the northeast, beyond the frontier. Evidence of this are the many border crossings which, although guarded by Roman soldiers, would have enabled a brisk trade, and the numerous Roman finds in "Free Germania" (as far as Jutland and Scandinavia). Attempts were occasionally also made, to settle Roman legions beyond the limes or, more often, to recruit auxiliaries. As a result, the Romanization of the population extended beyond the limes.

Research history

Interest in the limes as the remains of a site dating to the Roman period was rekindled in Germany at the time of the Renaissance and Renaissance humanism. This was bolstered by the rediscovery of the Germania and Annales of Tacitus in monastic libraries in the 15th and early 16th centuries.

Scholars like Simon Studion (1543-1605) researched inscriptions and discovered forts. Studion led archaeological excavations of the Roman camp of Benningen on the Neckar section of the Neckar-Odenwald Limes. Local limes commissions were established but were confined to small areas, for example, in the Grand Duchy of Hesse or Grand Duchy of Baden, due to the political situation. Johann Alexander Döderlein was the first person to record the course of the limes in the Eichstätt region. In 1723, he was the first to interpret the meaning of the limes correctly[2][3] and published the first scholarly treatise about it in 1731.

Imperial Limes Commission

Only after the foundation of the German Empire could archaeologists begin to study more precisely the route of the limes, about which there had previously only been a rudimentary knowledge. As a result, they were able to make the first systematic excavations in the second half of the 19th century. In 1892, the Imperial Limes Commission (RLK) was established for this purpose in Berlin, under the direction of the ancient historian, Theodor Mommsen. The work of this commission is considered pioneering for reworking of Roman provincial history. Especially productive were the first ten years of research, which worked out the course of the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes and named the camps along the border. The research reports on the excavations were published from 1894 to the dissolution of the Commission in 1937. The individual reports went under the title of The Upper Rhaetian Limes of the Roman Empire (ORL), which was published in fifteen volumes, of which seven cover the route of the limes and eight cover the various camps and forts. The documents of the Imperial Limes Commission are now in the custody of the Roman-Germanic Commission of the German Archaeological Institute. The RLK numbered the sections of the route, the forts and the watchtowers (Wp) on the individual sections.

Sections

In the course of this work the 550-kilometre-long route of the limes was surveyed, divided into sections and described. This division followed the administrative boundaries in 19th-century Germany and not that of ancient Rome:

- Section 1: Rheinbrohl – Bad Ems

- Section 2: Bad Ems – Adolfseck near Bad Schwalbach

- Section 3: Adolfseck near Bad Schwalbach – Taunus – Köpperner Tal

- Section 4: Köpperner Tal – Wetterau – Marköbel

- Section 5: Marköbel – Großkrotzenburg am Main

- Section 6a: Hainstadt – Wörth am Main (older Main Line)

- Section 6b: Trennfurt – Miltenberg

- Section 7: Miltenberg – Walldürn – Buchen-Hettingen (Rehberg)

- Section 8: Buchen-Hettingen (Rehberg) – Osterburken – Jagsthausen (more recent Odenwald Line)

- Section 9: Jagsthausen – Öhringen – Mainhardt – Welzheim – Alfdorf-Pfahlbronn (Haghof)

- Section 10: Wörth am Main – Bad Wimpfen (older Odenwald Line/ Neckar-Odenwald Limes)

- Section 11: Bad Wimpfen – Köngen (Neckar Line)

- Section 12: Alfdorf-Pfahlbronn (Haghof) – Lorch – Rotenbachtal near Schwäbisch Gmünd (end of the Upper Germanic Limes, start of the Rhaetian Limes) – Aalen – Stödtlen

- Section 13: Mönchsroth – Weiltingen-Ruffenhofen - Gunzenhausen

- Section 14: Gunzenhausen – Weißenburg – Kipfenberg

- Section 15: Kipfenberg – Eining

Literature

Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes in general

- Dietwulf Baatz: Der römische Limes. Archäologische Ausflüge zwischen Rhein und Donau. 4th edn. Gebrüder Mann, Berlin, 2000, ISBN 3-7861-1701-2.

- Thomas Becker, Stephan Bender, Martin Kemkes, Andreas Thiel: Der Limes zwischen Rhein und Donau. Ein Bodendenkmal auf dem Weg zum UNESCO-Weltkulturerbe. (= Archaeological information from Baden-Württemberg. Issue 44). Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart, 2001, ISBN 3-927714-60-7.

- Ernst Fabricius, Friedrich Leonhard, Felix Hettner, Oscar von Sarwey et al.: Der obergermanisch-raetische Limes des Roemerreiches. publ. by the Reichs-Limeskommission in at least 15 volumes. O. Petters, Heidelberg/Berlin/Leipzig, 1894–1937 (partial reprint: Codex-Verlag, Böblingen, 1973; full reprint: Greiner, Remshalden, 2005ff., ISBN 3-935383-72-X, ISBN 978-3-935383-61-5).

- Anne Johnson: Römische Kastelle des 1. und 2. Jahrhunderts n. Chr. in Britannien und in den germanischen Provinzen des Römerreiches. (= Kulturgeschichte der antiken Welt. Vol. 37). Zabern, Mainz, 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X.

- Martin Kemkes: Der Limes. Grenze Roms zu den Barbaren. 2nd, revised edition. Thorbecke, Ostfildern, 2006, ISBN 3-7995-3401-6.

- Hans-Peter Kuhnen (ed.): Gestürmt – Geräumt – Vergessen? Der Limesfall und das Ende der Römerherrschaft in Südwestdeutschland. Württembergisches Landesmuseum, Stuttgart, 1992, ISBN 3-8062-1056-X.

- Wolfgang Moschek: Der Limes. Grenze des Imperium Romanum. Primus, Darmstadt, 2014, ISBN 978-3-8631-2729-9.

- Jürgen Oldenstein (ed.): Der obergermanisch-rätische Limes des Römerreiches. Fundindex Fundindex. Zabern, Mainz, 1982, ISBN 3-8053-0549-4.

- Rudolf Pörtner: Mit dem Fahrstuhl in die Römerzeit. Econ, Düsseldorf 1959, 1965; Moewig, Rastatt, 1980, 2000 (divers further issues), ISBN 3-8118-3102-X.

- Britta Rabold, Egon Schallmayer, Andreas Thiel (eds.): Der Limes. Die Deutsche Limes-Straße vom Rhein zur Donau. Theiss, Stuttgart, 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1.

- Marcus Reuter, Andreas Thiel: Der Limes. Auf den Spuren der Römer. Theiss, Stuttgart, 2015, ISBN 978-3-806-22760-4.

- Egon Schallmayer: Der Limes. Geschichte einer Grenze. C. H. Beck, Munich, 2006, ISBN 3-406-48018-7 (scarce, current introduction.)

- Hans Schönberger: Die römischen Truppenlager der frühen und mittleren Kaiserzeit zwischen Nordsee und Inn. In: Bericht der Römisch-Germanischen Kommission. 66, 1985, pp. 321–495.

- Andreas Thiel: Wege am Limes. 55 Ausflüge in die Römerzeit. Theiss, Stuttgart, 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1946-X.

- Gerhard Waldherr: Der Limes. Kontaktzone zwischen den Kulturen. Reclam, Stuttgart, 2009, ISBN 978-3-15-018648-0.

Sections

- Willi Beck, Dieter Planck: Der Limes in Südwestdeutschland. 2nd edn., Konrad Theiß Verlag, Stuttgart, 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9.

- Thomas Fischer, Erika Riedmeier-Fischer: Der römische Limes in Bayern. Geschichte und Schauplätze entlang des UNESCO-Welterbes. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0.

- Jörg Heiligmann: Der "Alb-Limes". Ein Beitrag zur Besetzungsgeschichte Südwestdeutschlands. Theiss, Stuttgart, 1990, ISBN 3-8062-0814-X.

- Cliff Alexander Jost: Der römische Limes in Rheinland-Pfalz. (= Archäologie an Mittelrhein und Mosel, Vol. 14). Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Rheinland-Pfalz, Koblenz, 2003, ISBN 3-929645-07-6.

- Margot Klee: Der Limes zwischen Rhein und Main. Theiss, Stuttgart, 1989, ISBN 3-8062-0276-1.

- Margot Klee: Der römische Limes in Hessen. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg, 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2232-0.

- Egon Schallmayer: Der Odenwaldlimes. Entlang der römischen Grenze zwischen Main und Neckar. Theiss, Stuttgart, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8062-2309-5.

- Bernd Steidl: Welterbe Limes: Roms Grenze am Main. Logo Verlag, Obernburg am Main, 2008, ISBN 978-3-939462-06-4.

Maps

- Der Limes. Rheinbrohl – Holzhausen an der Heide. Topographische Freizeitkarte 1:25000 mit Limes-Wanderweg, Limes-Radweg, Deutsche Limesstraße. Publ.: Rhineland-Palatinate State Office of Survey and Geobasis Information in cooperation with the Rhineland-Palatinate State Office for Monument Conservation, Archaeological monument conservation, Koblenz Office. – Koblenz: State Office of Survey and Geobasis Information in cooperation with the Rhineland-Palatinate State Office for Monument Conservation, Koblenz Office 2006, ISBN 3-89637-378-1.

- Offizielle Karte UNESCO-Weltkulturerbe obergermanisch-raetischer Limes in Rheinland-Pfalz von Rheinbrohl bis zur Saalburg (Hessen). Jointly published by the Deutsche Limeskommission, Generaldirektion Kulturelles Erbe – Direktion Archäologie, verein Deutsche Limes-Straße, Landesamt für Vermessung und Geobasisinformation Rheinland-Pfalz. – Koblenz: Landesamt für Vermessung und Geobasisinformation Rheinland-Pfalz 2007, ISBN 978-3-89637-384-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Obergermanisch-Raetischer Limes. |

- Limesinformationszentrum Baden-Württemberg, retrieved 16 July 2010

- links and literature on the subject of the Limes

- The Limes in Hesse: multimedia dossier (diploma work during studies for online journalism at Darmstadt College)

- The Limes: then and now – archaeologie-online.de

- UNESCO Weltkulturerbe – the Upper Germanic-Rhatian Limes (the German website)

- Frontiers of the Roman Empire (English website)

- die-roemer-online.de Comprehensive work about the Roman Limes in Germany

- German Limes Commission

- The German Limes Road

- Limes film

- The Saalburg, an individually reconstructed Roman fort

- The Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes at the Hesse Cultural Portal

- Taunus-Wetterau Limes: comprehensive site on the Limes in Hesse

- www.antikefan.de – Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes (private website)

- Limes pages – The Romans in Baden-Württemberg (private website)

- Impressions of a Border – the Limes in Germany. A photo gallery of reconstructed limes sites

- The Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes SPIEGEL article dated 27 January 2009.

- AG Limes Öhringen Agenda Gruppe Limes with the municipalities of Schöntal, Jagsthausen, Forchtenberg, Zweiflingen, Pfedelbach and Mainhardt

- LIMES Action of the European Commission

- Virtual limes worlds

References

- ↑ Dietwulf Baatz: Die Saalburg – ein Limeskastell 80 Jahre nach der Rekonstruktion. In: Günter Ulbert, Gerhard Weber (eds.): Konservierte Geschichte? Antike Bauten und ihre Erhaltung. Konrad Theiss Verlag. Stuttgart, 1985, ISBN 3-8062-0450-0, p. 126; Ill. 127.

- ↑ Weißenburg stiftet eigenen Kulturpreis, published in 1986, retrieved 22 June 2016

- ↑ Bernhard Overbeck: Johann Alexander Döderlein (1675–1745) und die „vaterländische“ Numismatik, Brunswick, 2012, pp.147-165