Dorothea Tanning

| Dorothea Tanning | |

|---|---|

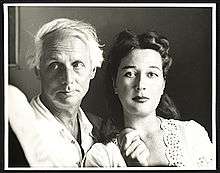

Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning in 1948. Photo by Robert Bruce Inverarity in the Smithsonian Institution collection. | |

| Born |

August 25, 1910 Galesburg, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died |

January 31, 2012 (aged 101) Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | United States |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture, printmaking, writing |

| Movement | Surrealism |

| Spouse(s) | Max Ernst (1946–76) |

Dorothea Margaret Tanning (August 25, 1910 – January 31, 2012) was an American painter, printmaker, sculptor, writer, and poet. Her early work was influenced by Surrealism.

Biography

Dorothea Tanning was born and raised in Galesburg, Illinois. After attending Knox College for two years (1928–30), she moved to Chicago in 1930 and then to New York in 1935. There she supported herself as a commercial artist while pursuing her own painting, and discovered Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art’s seminal 1936 exhibition, Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism. After an eight-year relationship, she was married briefly to the writer Homer Shannon in 1941. Impressed by her creativity and talent in illustrating fashion advertisements, the art director at Macy’s department store introduced her to the gallery owner Julien Levy, who immediately offered to show her work. Levy later gave Tanning two one-person exhibitions (in 1944 and 1948), and also introduced her to the circle of émigré Surrealists whose work he was showing in his New York gallery, including the German painter Max Ernst.[1]

Tanning first met Ernst at a party in 1942. Later he dropped by her studio to consider her work for an exhibition of work by women artists at The Art of This Century gallery, which was owned by Peggy Guggenheim, Ernst's wife at the time. As Tanning recounts in her memoirs, he was enchanted by her iconic self-portrait Birthday (1942, Philadelphia Museum of Art). The two played chess, fell in love, and embarked on a life together that took them to Sedona in Arizona, and later to France.[2][3] They lived in New York for several years before moving to Sedona, where they built a house and hosted visits from many friends crossing the country, including Henri Cartier-Bresson, Lee Miller, Roland Penrose, Yves Tanguy, Kay Sage, Pavel Tchelitchew, George Balanchine, and Dylan Thomas. Tanning and Ernst were married in 1946 in a double wedding with Man Ray and Juliet Browner in Hollywood.[4]

In 1949, Tanning and Ernst relocated to France, where they divided their time between Paris and Touraine, returning to Sedona for intervals through the early and mid 1950s. They lived in Paris and later Provence until Ernst's death in 1976, after which Tanning returned to New York.[5] She continued to create studio art in the 1980s, then turned her attention to her writing and poetry in the 1990s and 2000s, working and publishing until the end of her life. Tanning died on January 31, 2012, at her Manhattan home at age 101.[6][7]

Artistic career

Apart from three weeks she spent at the Chicago Academy of Fine Art in 1930,[8] Tanning was a self-taught artist.[9] The surreal imagery of her paintings from the 1940s and her close friendships with artists and writers of the Surrealist Movement have led many to regard Tanning as a Surrealist painter, yet she developed her own individual style over the course of an artistic career that spanned six decades.

Tanning’s early works – paintings such as Birthday and Eine kleine Nachtmusik (1943, Tate Modern, London) – were precise figurative renderings of dream-like situations. Like other Surrealist painters, she was meticulous in her attention to details and in building up surfaces with carefully muted brushstrokes. Through the late 1940s, she continued to paint depictions of unreal scenes, some of which combined erotic subjects with enigmatic symbols and desolate space. During this period she formed enduring friendships with, among others, Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Cornell, and John Cage; designed sets and costumes for several of George Balanchine's ballets, including The Night Shadow (1945) at the Metropolitan Opera House; and appeared in two of Hans Richter's avant-garde films.

Over the next decade, Tanning's painting evolved, becoming less explicit and more suggestive. Now working in Paris and Huismes, France, she began to move away from Surrealism and develop her own style. During the mid-1950s, her work radically changed and her images became increasingly fragmented and prismatic, exemplified in works such as Insomnias (1957, Moderna Museet, Stockholm). As she explains, "Around 1955 my canvases literally splintered... I broke the mirror, you might say.”

By the late 1960s, Tanning’s paintings were almost completely abstract, yet always suggestive of the female form. From 1969 to 1973, Tanning concentrated on a body of three-dimensional work, soft, fabric sculptures, five of which comprise the installation Hôtel du Pavot, Chambre 202 (1970–73) that is now in the permanent collection of the Musée National d'Art Moderne at the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. During her time in France in the 1950s-70s, Tanning also became an active printmaker, working in ateliers of Georges Visat and Pierre Chave and collaborating on a number of limited edition artists’ books with such poets as Alain Bosquet, Rene Crevel, Lena Leclerq, and André Pieyre de Mandiargues.[10] After her husband's death in 1976, Tanning remained in France for several years with a renewed concentration on her painting. By 1980 she had relocated her home and studio to New York and embarked on an energetic creative period in which she produced paintings, drawings, collages, and prints.

Tanning's work has been recognized in numerous one-person exhibitions, both in the United States and in Europe, including major retrospectives in 1974 at the Centre National d’Art Contemporain in Paris (which became the Centre Georges Pompidou in 1977), and in 1993 at the Malmö Konsthall in Sweden and the at the Camden Art Center in London. The New York Public Library mounted a retrospective of Tanning's prints in 1992,[11] and the Philadelphia Museum of Art mounted a small retrospective exhibition in 2000 entitled Birthday and Beyond to mark its acquisition of Tanning’s celebrated 1942 self-portrait, Birthday.

Tanning's 100th birthday in 2010 was marked by a number of exhibitions during the year: "Dorothea Tanning – Early Designs for the Stage" at The Drawing Center, New York, USA,[12] "Happy Birthday Dorothea Tanning" at the Maison Waldberg, Seillans, France,[13] "Zwischen dem Inneren Auge und der Anderen Seite der Tür: Dorothea Tanning Graphiken" at the Max Ernst Museum, Brühl, Germany,[14] "Dorothea Tanning: 100 years – A Tribute" at Galerie Bel’Art, Stockholm,[15] and "Surréalisme, Dada et Fluxus - Pour le 100ème anniversaire de Dorothea Tanning" at l'Espace d'Art, Rennes les Bains, France.[16]

Literary career

Tanning wrote stories and poems throughout her life, with her first short story published in VVV (magazine) in 1943[17] and original poems accompanying her etchings in the limited edition books Demain (1964)[18] and En chair et en or (1973).[19] However, it was after her return to New York in the 1980s that she began to focus on her writing. In 1986, she published her first memoir, entitled Birthday for the painting that had figured so prominently in her biography. It has since been translated into four other languages. In 2001, she wrote an expanded version of her memoir called Between Lives: An Artist and Her World.

With the encouragement of her friend and mentor James Merrill (who was for many years Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets),[20] Tanning began to write her own poetry in her eighties, and her poems were published regularly in literary reviews and magazines such as The Yale Review, Poetry, The Paris Review, and The New Yorker until the end of her life. A collection of her poems, A Table of Content, and a short novel, Chasm: A Weekend, were both published in 2004. Her second collection of poems, Coming to That, was published by Graywolf Press in 2011.

In 1994, Tanning endowed the Wallace Stevens Award of the Academy of American Poets, an annual prize of $100,000 awarded to a poet in recognition of outstanding and proven mastery in the art of poetry.

Bibliography

Books by Dorothea Tanning

- Coming to That: Poems, New York: Graywolf Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1-55597-601-9 (collection of poems)

- A Table of Content: Poems. New York: Graywolf Press, 2004. ISBN 1-55597-402-3 (collection of poems)

- Chasm: A Weekend. New York: Overlook Press, and London: Virago Press, 2004. ISBN 1-58567-584-9 (novel)

- Between Lives: An Artist and Her World. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001. ISBN 0-393-05040-8 (memoir)

- Birthday. Santa Monica: The Lapis Press, 1986. ISBN 0932499163 (memoir)

Monographs

- Bailly, Jean Christopher, John Russell, and Robert C. Morgan. Dorothea Tanning. New York: George Braziller, 1995. ISBN 0807614025

- Dorothea Tanning: Numéro Spécial de XXe Siècle. Paris: Editions XXe Siècle, 1977.

- Plazy, Giles. Dorothea Tanning. Paris: Editions Filipacchi, 1976 and (English translation) 1979. ISBN 2850181684

- Bosquet, Alain. La Peinture de Dorothea Tanning. Paris: Jean-Jacques Pauvert, 1966.

Exhibition catalogues

- Dorothea Tanning: Web of Dreams. London: Alison Jacques Gallery, 2014. ISBN 0957226942

- Dorothea Tanning: Unknown but Knowable States. San Francisco: Gallery Wendi Norris, 2013. ISBN 0615720900

- Greskovic, Robert, Joanna Kleinberg, and Rachel Liebowitz. Dorothea Tanning: Early Designs for the Stage. New York: The Drawing Center, 2010. ISBN 0942324560

- Dorothea Tanning: Beyond the Esplanade: Paintings, Drawings and Prints from 1940 to 1965. San Francisco: Frey Norris Gallery, 2009. ISBN 9780982393246

- Dorothea Tanning: Insomnias, Paintings from 1954 to 1965. New York: Kent Fine Art, 2005. ISBN 1878607952

- Nordgren, Sune, John Russell, Alain Jouffroy, Jean-Christophe Bailly, and Lasse Söderberg. Dorothea Tanning: Om Konst Kunde Tala (If Art Could Talk). Malmö, Sweden: Malmö Konsthall, 1993. ISBN 9177040597

- Waddell, Roberta, and Louisa Wood Ruby, eds., with texts by Donald Kuspit and Dorothea Tanning. Dorothea Tanning: Hail Delirium! A Catalogue Raisonné of the Artist’s Illustrated Books and Prints, 1942-1991. New York: The New York Public Library, 1992. ISBN 0871044307

- Dorothea Tanning: Between Lives--Works on Paper. London: Runkel-Hue-Williams Ltd., 1989.

- Eleven Paintings by Dorothea Tanning. New York: Kent Fine Art, 1988.

- Dorothea Tanning on Paper, 1948-1986. New York: Kent Fine Art, 1987.

- Dorothea Tanning: 10 Recent Paintings and a Biography. New York: Gimpel-Weitzenhoffer Gallery, 1979.

- Jouffroy. Alain. Dorothea Tanning: Oeuvre. Paris: Centre National D'Art Contemporain, 1974.

- Waldberg, Patrick. Dorothea Tanning, Casino Communal, XXe Festival Belge D'Été. Brussels: André de Rache, 1967.

Interviews

- *Glassie, John. "Oldest living surrealist tells all." Salon.com, Feb. 11, 2002.

- *Yablonsky, Linda. “Surrealist Views From a Real Live One.” The New York Times, March 24, 2002.

- *Kimmelman, Michael. "Interwoven Destinies As Artist and Wife." The New York Times, August 24, 1995.

Obituaries

- Obituary in Gallerist NY

- Obituary in The Independent by Marcus Williamson

- Obituary on Liveauctioneers.com

- Obituary in The Los Angeles Times

- Obituary in The New York Times

Quotes

In a 2002 interview for Salon.com in response to: "So what have you tried to communicate as an artist? What were your goals, and have you achieved them?" Tanning replies: "I’d be satisfied with having suggested that there is more than meets the eye."[21] And in response to: "What do you think of some of the artwork being produced today?" Tanning replies: "I can’t answer that without enraging the art world. It’s enough to say that most of it comes straight out of dada, 1917. I get the impression that the idea is to shock. So many people laboring to outdo Duchamp’s urinal. It isn’t even shocking anymore, just kind of sad."[22]

When speaking on her relationship with Ernst in an interview, Tanning said: "I was a loner, am a loner, good Lord, it's the only way I can imagine working. And then when I hooked up with Max Ernst, he was clearly the only person I needed and, I assure you, we never, never talked art. Never."[23]

"If it wasn’t known that I had been a Surrealist, I don’t think it would be evident in what I’m doing now. But I’m branded as a Surrealist. Tant pis."[24]

"Women artists. There is no such thing—or person. It’s just as much a contradiction in terms as “man artist” or “elephant artist.” You may be a woman and you may be an artist; but the one is a given and the other is you."[24]

Public collections

- Centre Georges Pompidou / Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris (see works)

- Museum of Modern Art, New York (see works)

- Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. (see works)

- Tate Modern, London (see works)

- Philadelphia Museum of Art (see works)

- Hood Museum of Art, Hanover, New Hampshire (see works)

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (see works)

See also

References

- ↑ Tanning, Dorothea. Between Lives: An Artist and Her World. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

- ↑ Tanning, Dorothea. Birthday. Santa Monica: The Lapis Press, 1986.

- ↑ Tanning, Between Lives, 2001.

- ↑ "Dorothea Tanning". The Daily Telegraph. 5 February 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ "Artist's Chronology." Bailly, Jean Christopher, et al. Dorothea Tanning. New York: George Braziller, 1995.

- ↑ Glueck, Grace (3 February 2012). "Dorothea Tanning, Surrealist Painter, Dies at 101". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ Needham, Alex (2 February 2012). "Dorothea Tanning, surrealist artist, dies aged 101". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ Bailly, 1995, p. 356.

- ↑ ...], [contributors Rachel Barnes (2001). The 20th-Century art book. (Reprinted. ed.). London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0714835420.

- ↑ Waddell, Roberta, and Ruby, Louisa Wood, eds., Dorothea Tanning: Hail Delirium! A Catalogue Raisonné of the Artist’s Illustrated Books and Prints, 1942-1991. New York: The New York Public Library, 1992.

- ↑ Waddell, et al, 1992.

- ↑

- ↑ "Fine Arts - exhibitions and tours en la Costa Azul". Cote.azur.fr. 2015-07-27. Retrieved 2015-07-31.

- ↑ "Dorothea Tanning zum 100. Geburtstag - Brühl - Brühler Schlossbote". Schlossbote.de. Retrieved 2015-07-31.

- ↑ "Galerie Bel'Art - Stockholm". Belart.se. 2010-09-22. Retrieved 2015-07-31.

- ↑ "Espace d'Art, Galerie de Rennes les Bains, Aude, France - Expositions 2010". Audeculture.com. Retrieved 2015-07-31.

- ↑ Tanning, Dorothea. “Blind Date.” VVV, nos. 2-3 (March 1943), p. 104

- ↑ Tanning, Dorothea. Demain (Tomorrow). Editions Georges Visat et Cie., Paris, 1964.

- ↑ Tanning, Dorothea. En chair et en or (In Flesh and Gold). Éditions Georges Visat, Paris, 1973

- ↑ Poetry Foundation, Dorothea Tanning, 1910-2012, online biography, accessed 18 May 2013.

- ↑ Glassie, John. "Oldest Living Surrealist Tells All (interview)". Salon.com. 11 February 2002.

- ↑ Glassie, 2002.

- ↑ McCormick, Carlo (Fall 1990). "Dorothea Tanning". BOMB Magazine. New Art Publications (33). Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- 1 2 McCormick, 1990.

External links

- Dorthea Tanning on Wikiart.org

- Dorothea Tanning official website

- Dorothea Tanning on artnet Monographs

- Examples of paintings 1978-1997

- Ten Dreams Galleries

- Academy of American Poets