Cuyahoga Valley National Park

| Cuyahoga Valley National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

|

Bedrock outcrops, such as this one, can be found throughout the park. | |

| |

| Location | Summit County & Cuyahoga County, Ohio, USA |

| Nearest city | Cleveland, Akron |

| Coordinates | 41°14′30″N 81°32′59″W / 41.24167°N 81.54972°WCoordinates: 41°14′30″N 81°32′59″W / 41.24167°N 81.54972°W |

| Area | 32,950 acres (13,334 ha; 51 sq mi)[1] |

| Established | October 11, 2000 |

| Visitors | 2,284,612 (in 2015)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Cuyahoga Valley National Park |

Cuyahoga Valley National Park is a United States national park that preserves and reclaims the rural landscape along the Cuyahoga River between Akron and Cleveland in Northeast Ohio. The 32,950-acre (13,334 ha; 51 sq mi)[3] park is administered by the National Park Service and is the only national park in Ohio. It was established in 1974 as the Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area and was designated as a national park in 2000.

Wildlife

Animals found in the park are include raccoons, muskrats, coyotes, skunks, red foxes, beavers, peregrine falcons, river otters, bald eagles, opossums, three species of moles, white-tailed deer, Canada geese, gray foxes, minks, great blue herons, and seven species of bats.[4]

Administrative history

The valley began providing recreation for urban dwellers in the 1870s when people came from nearby cities for carriage rides or leisure boat trips along the canal. In 1880, the Valley Railroad became another way to escape urban industrial life. Actual park development began in the 1910s and 1920s with the establishment of Cleveland and Akron metropolitan park districts. In 1929 the estate of Cleveland businessman Hayward Kendall donated 430 acres (170 ha) around the Richie Ledges and a trust fund to the state of Ohio. Kendall's will stipulated that the "property should be perpetually used for park purposes". It became Virginia Kendall park, in honor of his mother. In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps built much of the park's infrastructure including what are now Happy Days Lodge and the shelters at Octagon, Ledges, and Kendall Lake.

Although the regional parks safeguarded certain places, by the 1960s local citizens feared that urban sprawl would overwhelm the Cuyahoga Valley's natural beauty. Active citizens joined forces with state and national government staff to find a long-term solution. Finally, on December 27, 1974, President Gerald Ford signed the bill establishing the Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area.

The National Park Service acquired the 47-acre (19 ha) Krejci Dump in 1985 to include as part of the recreation area. They requested a thorough analysis of the site's contents from the Environmental Protection Agency. After the survey identified extremely toxic materials, the area was closed in 1986 and designated a superfund site.[5] Litigation was filed against potentially responsible parties, which included Ford, GM, Chrysler, 3M, and Waste Management of Ohio. All the companies except 3M agreed to a settlement; 3M lost at trial.[6]

Cleanup began in 1987 and had not been completed as of mid-2011, although most of the area had been restored to its original state as wetlands.[7]

The area was redesignated a national park by Congress on October 11, 2000,[8] with the passage of the Department of the Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2001, House Bill 4578, 106th congress.[9] It is administered by the National Park Service. David Berger National Memorial in Beachwood, Ohio is also managed through Cuyahoga Valley National Park.

The Richfield Coliseum, a multipurpose arena in the Cuyahoga River area, was demolished in 1999 and the now-empty site became part of Cuyahoga Valley National Park upon its designation in 2000. It has since become a grassy meadow popular with birdwatchers.

Attractions

Many visitors spend their time hiking or bicycling the park's many trails which visit its numerous attractions, including the crushed limestone along portions of the 20-mile (32 km) Towpath Trail, following a former stretch of the 308-mile (496 km) Ohio and Erie Canal.

Waterfalls, rolling hills, caves and winding river scenery attract many park visitors. Steep narrow ravines, a rolling floodplain, and lush farmland contrast with one another throughout the park. Animal life is also plentiful. The Ledges provides a boulder-strewn cliff to relax and watch the sunset over the wooded scenery below. Sled-riding is popular during the winter at Kendall Hills.[10]

The park offers an array of preserved and restored displays of 19th and early 20th century sustainable farming and pastoral or rural living, while catering to contemporary interests with art exhibits, outdoor concerts, and scenic excursion and special event railroad tours on the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad.[11]

It includes compatible-use sites not owned by the federal government, including several local regional parks in the Cleveland Metroparks and Metro Parks, Serving Summit County systems, Blossom Music Center, and the Hale Farm & Village. In the mid-1980s, the park hosted the National Folk Festival.

Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail

The multi-purpose Ohio & Erie Canal Towpath trail was developed by the National Park Service and is the major trail through Cuyahoga Valley National Park. It runs almost 21 miles (33½ km) from Rockside Road, Independence, OH in the north to Summit County's Bike & Hike trail in the south. It follows the Cuyahoga River for much of its length. Restrooms can be found at several trailheads along the way and commercial food and drink can be found on Rockside Rd., the Boston Store, in Peninsula, and at the farmer's market on Botzum Rd., (seasonally). There are also several visitors centers along the way. At Rockside Rd. it connects to Cleveland Metroparks trail which travels another 6 miles (9½ km) North. The Summit County trail runs through Akron and south. The "towpath trail" continues through Stark and Tuscarawas counties down to Zoar, Ohio; almost 70 more miles with only one significant (1 mile) interruption. Sections of the towpath trail outside of Cuyahoga Valley National Park are owned and maintained by various state and local agencies. The trail also meets the Buckeye Trail in the National Park (near Boston Store). Another section of the Summit County Bike & Hike Trail system (connecting to the nearby Brandywine Falls, and also to the Cleveland Metroparks Bedford Reservation and Solon in Cuyahoga County; Hudson and Stow in Summit County; and Kent and Ravenna in Portage County, Ohio) is near-by.

Seasonally, the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad allows visitors to travel along the towpath from Rockside Rd. to Akron getting off/on at any of the 6 other stops along the way. This is especially popular with bikers and for viewing and photographing fall colors. CVSR is independently owned and operated, check their website for days and times.

History

The Towpath Trail follows the historic route of the Ohio & Erie Canal. Before the canal was built, Ohio was a sparsely settled wilderness where travel was difficult and getting crops to market was nearly impossible. The canal, built between 1825 and 1832, provided a successful transportation route from Cleveland, on Lake Erie, to Portsmouth, on the Ohio River. The canal opened up Ohio to the rest of the settled eastern United States.[12]

There are numerous wayside exhibits that provide information about canal features and sites of historic interest.[13] There is also a virtual tour.[12][14]

Today visitors can walk or ride along the same path that the mules used to tow the canal boats loaded with goods and passengers. The scene is different than it was then; the canal was full of water carrying a steady flow of boats amongst the constant conversations of "canawlers." Evidence of beavers can be seen in many places along the trail.[12]

Stanford House (Formerly Stanford Hostel)

Located in the scenic Cuyahoga Valley near Peninsula, Ohio, Stanford House is a historic 19th-century farm home built in the 1830s by George Stanford, one of the first settlers in the Western Reserve. In 1978, the NPS purchased the property to act as a youth hostel in conjunction with the American Youth Hostels (AYH) organization. In March 2011, Stanford Hostel became Stanford House, Cuyahoga Valley National Park's first in-park lodging facility. The home was renovated by the Conservancy for Cuyahoga Valley National Park[15] and the National Park Service.[16][17]

Towpath trailheads

| Coordinates | Trailhead Map | Address | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lock 39 | |||

| 41°22′24″N 81°36′59″W / 41.373272°N 81.616382°W | Canal Visitor Center | Canal Road & Hillside Road, Valley View, Ohio 44125, 1 1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) south of Rockside Road | |

| Frazee House | Canal Road, Valley View, Ohio, 3 1⁄2 miles (5.6 km) south of Rockside Road |  | |

| 41°19′10″N 081°35′15″W / 41.31944°N 81.58750°W[18] | Station Road Bridge | ||

| Red Lock | |||

| Boston Store | Boston Mills Road, 1⁄10 mile (160 m) east of Riverview Road | ||

| Lock 29 | |||

| Hunt Farm Visitor Information Center | Bolanz Road, between Akron-Peninsula Road and Riverview Road | ||

| Ira | |||

| Indian Mound |

Geology

The "V" course of the Cuyahoga River is rather unique, first flowing southwest, and then abruptly turning north to drain into Lake Erie not far from its origin. The left arm of this "V", flowing north through the park, corresponds to an older preglacial valley, while the right arm corresponds to relatively new drainage. The new segment cut into the old at Cuyahoga Falls, the base of the "V". Other streams have made routes into the Cuyahoga preglacial valley by cutting gorges with waterfalls such as those found with the Tinkers, Brandywine and Chippewa Creeks. These waterfalls form when waterflow erodes the Bedford Shale, which underlies the more resistant Berea Sandstone. Glacial drift fills the valley to a depth of 400 feet. This fill is very complex due to ponding in front of the ice before and after each glaciation. Beach deposits, gravel bars and other shoreline deposits from Lake Maumee are found in the valley, as are gravels from the time of Lake Arkona, and ridges marking the shores of Lake Whittlesey, Lake Warren, and Lake Wayne.[19][20]

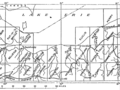

A noticeable remnant of the Wisconsin glaciation is the Defiance Moraine, which trends from Defiance in western Ohio, across the state into Pennsylvania. As Cushing et al point out, "The Defiance moraine represents the last notable stand of the glacial front in this region." The moraine varies in width from 2 to 4 miles, and according to Leverett, "it is like a broad wave whose crest stands 20 to 50 feet above the border of the plain outside it." This moraine forms a lobe that protrudes south into the valley for 8 miles all the way to Peninsula, the lobe being 6 miles wide at the north end, tapering to 3 miles wide at the south end. Kames and eskers mark the terrain south of this moraine up to the southern extent of the glaciation.[20]:63-64,96[19]:581-584[21]

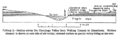

The Berea Sandstone and the Bedford Shale were deposited in a river delta environment in the Lower Mississippian. River channels were incised into the Bedford Shale and subsequently these channels were filled by the Berea Sandstone. Besides setting the stage for majestic gorges and waterfalls within the valley, they have provided an economic use as well. The Berea Sandstone was quarried in Berea for grindstones and building stones, while the lowermost part of the Bedford Shale was quarried in South Euclid and Cleveland Heights for its "bluestone".[22][20]:109-111

The Sharon Conglomerate is a Lower Pennsylvanian formation composed of sandstone and conglomerate. It forms, according to Cushing et al, "disconnected patches or outliers that cap the highest hills...these outliers stand boldly above the surrounding country" due to its resistance to erosion. The Boston Ledges are the most noteworthy example. As the Mississippian shale underneath is washed away, huge blocks of the Sharon result from the settling. As Cushing et al explain, "frost action aids in pushing these blocks apart, cracks are widened into caves, and a tangle of blocks results, separated by passages of uneven widths."[20]:54-57

Shale gas has been produced in the area since 1883, when H.A. Mastick's well was drilled in the Rockport Township to a depth of 527 feet, yielding 21,643 cubic feet of gas daily. A gas boom occurred in 1914/1915, and by 1931, several hundred gas wells were producing from the Devonian Huron shale. Production came from shales 1,250 feet thick at depths from 400 to 1,840 feet. Pressures were 3 to 135 psi flowing less than 20,000 cubic feet of gas daily, but was sufficient to furnish light for a house or two, and sometimes heat. As Cushing et al pointed out in the 1930s, "there are vast amounts of petroleum in the Devonian shales." Since then, the Marcellus Shale and the deeper Utica Shale have shown their economic potential.[20]:115-116,123

Map tracing the extent of the Defiance Moraine

Map tracing the extent of the Defiance Moraine Geologic map of surface glacial features

Geologic map of surface glacial features Ohio glacial boundary

Ohio glacial boundary Geologic map of rock outcrops: Qgd = Quaternary glacial drift from the Pleistocene, Cc = Cleveland Shale, Cbd and Cbe = Bedford Shale, and Cb = Berea Sandstone

Geologic map of rock outcrops: Qgd = Quaternary glacial drift from the Pleistocene, Cc = Cleveland Shale, Cbd and Cbe = Bedford Shale, and Cb = Berea Sandstone Geologic cross section

Geologic cross section Deposition of the Berea channel sandstone within the Bedford shale during the Lower Mississippian

Deposition of the Berea channel sandstone within the Bedford shale during the Lower Mississippian

Visitor centers

| Coordinates |

Visitor Center |

Address |

Description [23] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41°22′24″N 81°36′59″W / 41.373272°N 81.616382°W | Canal | Canal Road & Hillside Road, Valley View, Ohio 44125, 1 1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) south of Rockside Road | Canal Visitor Center contains exhibits and a bookstore. Exhibits illustrate 12,000 years of history in the valley, including the history of the canal. The canal-era building once served canal boat passengers waiting to pass through Ohio & Erie Canal Lock 38. Canal lock demonstrations are conducted seasonally on weekends by National Park Service staff and by volunteers wearing period costumes. A 20-minute slide program about the park and three, 30-minute videos on canal history are shown on request. |

| Happy Days | State Route 303, 1 mile (1.6 km) west of State Route 8, 2 miles east of the Village of Peninsula, Ohio | Happy Days was constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1938 and 1939 as a camp for urban children. The visitor center offers information and a variety of activities, including concerts, lectures, plays, and special events. A 20-minute slide program about the park is shown on request. Several hiking trails are located nearby. | |

| Boston Store | Boston Mills Road, 1⁄10 mile (160 m) east of Riverview Road | Boston Store was constructed in 1836 and has been used as a warehouse, store, post office, and gathering place. It is now a museum featuring exhibits relating to canal boat-building. | |

| Hunt Farm | Bolanz Road, between Akron-Peninsula Road and Riverview Road | The Hunt Farm property is typical of the small family farms that dotted the Cuyahoga Valley in the late 19th century. Here you can get information about park activities and see exhibits about the area's agricultural history. Next to the Ohio & Erie Canal Towpath Trail, it is an ideal starting point for a hike or a bicycle ride. | |

| Frazee House | Canal Road, Valley View, Ohio, 3 1⁄2 miles (5.6 km) south of Rockside Road | The Frazee House was constructed in 1825 and 1826, during the same years the northern section of the Ohio & Erie Canal was dug. It is a fine example of a Western Reserve home and features exhibits relating to architectural styles, construction techniques, and the Frazee family. | |

| 41°14′32″N 81°32′57″W / 41.242287°N 81.549124°W | Peninsula Depot | 1630 West Mill Street, Village of Peninsula, Ohio 44264, north of State Route 303 | The Peninsula Depot was originally located in the village of Boston, just north of Boston Mills Road. It was moved to Peninsula in the late 1960s. The building may be the only surviving combination station from the Valley Railway, which operated between Cleveland, Ohio and Tuscarawas County, Ohio in the late 19th century. Today the Peninsula Depot serves as an information and orientation center for people on foot, bike, and rail, and serves as a station for Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad (CVSR) excursions. Exhibits highlight the history and recreational opportunities of the area. |

Points of historic interest

| Coordinates |

Location |

Description |

|---|---|---|

| 41°22′24″N 81°36′59″W / 41.37333°N 81.61639°W | Canal Visitor Center - "Hell's Half Acre" | Exhibits related to human history in the valley and Ohio & Erie Canal history are available at Canal Visitor Center. The exhibits are housed in a renovated canal-era tavern that, for some time, had such a colorful reputation that it came to be called "Hell's Half Acre." Lock 38 is located in the front; lock demonstrations are offered by volunteers and staff in period costume every Saturday, Sunday, and holiday during the summer months. A lock model is located inside the visitor center. The ranger at the information desk will perform lock model demonstrations on request. An auditorium in the basement is used to show three different canal-related videos and one park orientation slide program. These programs will be run on request.[24] |

| Ohio & Erie Canal Related Structures | The Ohio & Erie Canal was constructed between 1825 and 1832. It successfully provided Ohio with a transportation system that permitted residents to conduct trade with the world. While it stopped functioning after the Great Flood of 1913, remnants and ruins of canal-related structures can be seen alongside the Ohio & Erie Canal Towpath Trail. Wayside exhibits explain the function of many of the structures visible from the trail. Our Towpath Trail Sites to Visit list may be useful in directing you to the points of greatest interest.[25][26] | |

| Frazee House | The Frazee House was under construction in 1825 when the canal was dug through its front yard. It's a great place to visit for information about Western Reserve architecture and construction techniques as well as some tidbits about the Frazee family.[27] | |

| Boston Store | This early canal-era building was owned by the Boston Land & Manufacturing Company. The Boston Store now houses numerous exhibits relating to canal boat building.[28] | |

|

Everett Road Covered Bridge | The Everett Road Covered Bridge was constructed after a local resident was killed attempting to cross the swollen Furnace Run in 1877. It was destroyed by storm floodwaters in 1975 and reconstructed by the National Park Service in 1986. It is the only covered bridge in Summit County today. The bridge is located on Everett Road about 1⁄2 mile (800 m) west of Riverview Road near Everett Village.[29] |

| Brandywine Village | Brandywine Village was conceived and founded by George Wallace, who built a sawmill next to Brandywine Falls in 1814. He encouraged others to move to the area, including his brother-in-law, who built a grist mill on the opposite side of the falls. With inexpensive land available and the presence of mills to provide lumber, flour, and corn meal, the Village of Brandywine began to grow. Today only a couple of buildings remain from the village but historic photos and remnants of building foundations allow us to remember the Brandywine Village that once was.[30] | |

| Civilian Conservation Corps Structures | The Civilian Conservation Corps was responsible for the construction of some of the most attractive buildings in the valley. Happy Days Visitor Center as well as the Ledges, Octagon, and Lake Shelters were built of wormy American Chestnut wood in the late 1930s. These structures can be found in the Virginia Kendall Unit of the park.[31][32] | |

| The George Stanford House | James Stanford moved to Boston Township immediately after surveying and naming it in 1806. He and with his wife Polly and son George were the first homesteaders in what is today Cuyahoga Valley National Park (CVNP). His son George built a stately Greek revival home in about 1830. That home, located at 6093 Stanford Road, now serves as the Cuyahoga Valley HI-Stanford Hostel.[33] | |

| National Register of Historic Places | This page contains a complete list of National Register of Historic Places locations within CVNP. Some of these locations are privately owned.[34] | |

| Hale Farm & Village | Hale Farm & Village is an outdoor living history museum that is just a few miles and 150 years away. Costumed "pioneer" interpreters describe life in the Western Reserve during the formative years of the United States of America. The village features 21 historic buildings to tour and many talented craftspeople. It is operated by the Western Reserve Historical Society.

Craft demonstrations include glassblowing, candlemaking, broommaking, spinning & weaving, cheesemaking, blacksmithing, woodworking, sawmilling, hearth cooking, and pottery making. The farm also features oxen, sheep, cows, and gardens.[35] |

National Register of Historic Places

Many of the listed homes are in private ownership.[37]

| # | Coordinates |

Locale |

Historic |

Status |

Address |

Register Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuyahoga County and Summit County | ||||||

| 1 | Agricultural Resources of Cuyahoga Valley | Multiple Property Document Form | no public facilities | 3/12/93 | ||

| 2 | Independence to Akron | Valley Railway Historic District | Cuyahoga Valley between Rockside Rd at CVNP and Howard St at Little Cuyahoga Valley. | 5/17/85 | ||

| 3 | Recreation/Conservation Resources of Cuyahoga Valley | Multiple Property Document Form | 1/10/97 | |||

| Cuyahoga County | ||||||

| 4 | Bedford | Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad Bridge | open to the public | Tinkers Creek | 7/24/75 | |

| 5 | 41°19′17″N 081°35′14″W / 41.32139°N 81.58722°W[38] | Brecksville | Brecksville-Northfield High Level Bridge - state highway bridge | open to the public | Ohio State Route 82 and Cuyahoga River (also in Northfield, Summit County, Ohio) Best viewed from Station Road Bridge Trailhead on the Towpath Trail (Riverview Rd just South of Ohio State Route 82) | 1/6/86 |

| 6 | Brecksville | Burt, William House | no public facilities | 9525 Brecksville Road | 3/7/79 | |

| 7 | Brecksville | Rich, Charles B., House | no public facilities | 9367 Brecksville Rd. | 2/22/79 | |

| 8 | Brecksville | Brecksville Trailside Museum - (Cleveland Metroparks Nature Center) | Chippewa Creek Drive off Ohio State Route 82 | 9?/92 | ||

| 9 | Brecksville vicinity | Coonrad, Jonas, House | no public facilities | 10340 Riverview Road | 7/24/79 | |

| 10 | Brecksville vicinity | Vaughn Site (33CU65) Address Restricted | no public facilities | 11/12/87 | ||

| 11 | Brecksville vicinity | Vaughn, Richard Farm | no public facilities | 9570 Riverview Road | 3/12/93 | |

| 12 | Independence | Packard-Doubler House | no public facilities - private property | 7634 Riverview Road | 3/9/79 | |

| 13 | Independence vicinity | South Park Site | no public facilities | Address Restricted | 6/22/76 | |

| 14 | Independence vicinity | Terra Vista Archeological District | no public facilities | Address Restricted | 5/23/78 | |

| 15 | Independence to Akron Valley Railway Historic District | Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad | open to the public for scenic train rides | Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area Between Rockside Rd and Howard St at Little Cuyahoga Valley | 5/17/85 | |

| 16 | Valley View | Frazee, Stephen House | CVNP Visitor Center with limited open hours | 7733 Canal Road | 5/4/76 | |

| 17 | Valley View | Gleason, Edmund House | no public facilities | 7243 Canal Rd | 12/18/79 | |

| 18 | Valley View | Gleason Farm - Boundary Increase | no public facilities | 7243 Canal Rd | 3/12/93 | |

| 19 | Valley View | Knapp, William, House | no public facilities | 7101 Canal Road | 3/19/79 | |

| 20 | Valley View | Lock 37 and Spillway Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | Fitzwater Road | 12/11/79 | |

| 21 | Valley View | Lock 38 and Spillway Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | Hillside Road | 12/11/79 | |

| 22 | Valley View | Lock 39 and Spillway Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | Canal Road | 12/11/79 | |

| 23 | 41°22′24″N 81°36′59″W / 41.37333°N 81.61639°W | Valley View | Inn at Lock 38 a.k.a. Canal Visitor Center - CVNP Visitor Center | a.k.a. Hell's Half Acre Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail, 7104 Canal Road | 12/11/79 | |

| 24 | 41°21′53″N 081°36′32″W / 41.36472°N 81.60889°W[39] | Valley View | Tinkers Creek Aqueduct Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | Tinkers Creek | 12/11/79 |

| 25 | Valley View | Ulyatt, Abraham, House | no public facilities | 6579 Canal Road | 2/27/79 | |

| 26 | Valley View | Wilson Feed Mill | open to public as a feed and grain store | Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail, 7604 Canal Road | 12/17/79 | |

| 27 | Valley View Village | Ohio and Erie Canal | open to the public via the towpath trail | Ohio State Route 631 | 11/13/65 NHL 11/13/66 | |

| Summit County | ||||||

| 28 | Akron Vicinity | Barker Village Site | no public facilities | Address Restricted | 04/19/78 | |

| 29 | Bath | Hale, Jonathan Homestead - Hale Farm and Village | open to the public | 2686 Oak Hill Road | 4/23/73 | |

| 30 | Boston | Boston Land and Manufacturing Company Store a.k.a. Boston Store | CVNP Visitor Center with limited open hours | Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail, Boston Mills Rd | 12/11/79 | |

| 31 | Boston | Lock 32 Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | 800 ft (240 m) N of Boston Mills Road | 12/11/79 | |

| 32 | Boston | Boston Mills Historic District | most buildings are private with no public facilities | Boston Mills Rd, Stanford Rd & Main Street | 11/9/92 | |

| 33 | Boston vicinity | Lock 33 Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | 1 mi (1.6 km) S of Highland Road | 12/11/79 | |

| 34 | Botzum | Botzum Farm | no public facilities | 11/01/96 - Determination of Eligibility | ||

| 35 | Cuyahoga Falls | Hunt/Wilke Farm a.k.a. Hunt Farm Visitor Information Center | CVNP Visitor Center with limited open hours | Agricultural Resources of Cuyahoga Valley MPD, 2049 Bolanz Road | 3/12/93 | |

| 36 | Brecksville vicinity | Jaite Mill Historic District - CVNP headquarters | no visitor facilities | SE of Brecksville at Riverview and Vaughn Roads | 5/21/79 | |

| 37 | 41°19′10″N 081°35′15″W / 41.31944°N 81.58750°W[18] | Brecksville vicinity | Station Road Bridge | open to the public | East of Brecksville at Cuyahoga River | 3/7/79 |

| 38 | Everett | Lock 27 Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | Approx 400 ft (120 m) E of intersection of Riverview and Everett Roads | 3/12/93 | |

| 39 | Everett vicinity | Everett Knoll Complex Prehistoric District | no public facilities | Address Restricted | 5/25/77 | |

| 40 | Everett vicinity | Furnace Run Aqueduct Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | Furnace Run | 12/11/79 | |

| 41 | Everett | Everett Historic District | Village is open to the public - some buildings are private residences - NPS buildings have no visitor facilities | Everett and Riverview Roads | 1/14/94 | |

| 42 | Ira | Lock 26 Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | 3.3 mi (5.3 km) N of Ira Road | 12/11/79 | |

| 43 | Northfield Center vicinity | Wallace Farm | open to patrons of the bed & breakfast only (Inn at Brandywine Falls) | 8230 Brandywine Rd | 6/27/85 | |

| 44 | Peninsula | Everett Road Covered Bridge | open to the public | SW of Peninsula on Everett Rd over Furnace Creek | 5/23/73 Demolished/Destroyed/Rebuilt | |

| 45 | Peninsula | Lock 28 Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | Deep Lock Quarry Metro Park | 12/11/79 | |

| 46 | Peninsula | Lock 29 and Aqueduct Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | off Ohio State Route 303 | 12/11/79 | |

| 47 | Peninsula | Lock 30 and Feeder Dam Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | Off Ohio State Route 303 | 12/11/79 | |

| 48 | Peninsula | Lock 31 Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | 200 ft (61 m) E of Cuyahoga River and approx 0.5 mi (800 m) S of Ohio Turnpike | 12/11/79 | |

| 49 | 41°14′32″N 81°32′57″W / 41.24222°N 81.54917°W | Peninsula | Peninsula Village Historic District | most buildings are private - some are retail stores | Both sides of Ohio State Route 303 | 8/23/74 |

| 50 | Peninsula | Fox House | no public facilities - private property | 1664 West Main Street | Part I Certification (contributes to the significance of the above-named district and is a certified historic structure for purposes of rehabilitation) 2/13/87, MARO | |

| 51 | Peninsula | Tilden, Daniel, House | no public facilities - private property | 2325 Stine Rd | 6/20/85 | |

| 52 | Peninsula | Welton, Allen, House | no public facilities - private property | 2485 Major Rd | 5/07/79 | |

| 53 | Peninsula vicinity | Brown, Jim, House | no public facilities | S of Peninsula at 3491 Akron Peninsula Rd | 3/2/79 | |

| 54 | Peninsula vicinity | Brown/ Bender Farm, Boundary Increase | no public facilities | 3491 Akron Peninsula Rd | 3/12/93 | |

| 55 | Peninsula vicinity | Cranz, Edward Farm | no public facilities | 2780 Oak Hill Drive | 3/12/93 | |

| 56 | Peninsula vicinity | Cranz, William and Eugene Farm | no public facilities | 2401 Ira Road | 3/12/93 | |

| 57 | Peninsula vicinity | Stanford, George, Farm - (AYH Youth Hostel) | 6093 Stanford Rd | 2/17/82 | ||

| 58 | Peninsula vicinity | Stumpy Basin Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | 200 ft (61 m) E of Cuyahoga River and approx 0.5 mi (800 m) S of Ohio Turnpike | 12/11/79 | |

| 59 | Peninsula vicinity | Duffy, Michael Farm | no public facilities - private property | 4965 Quick Road | 3/12/93 | |

| 60 | Peninsula vicinity | Virginia Kendall Historic District | open to the public - shelter, restrooms, winter sports center | Truxell Road | 1/10/97 | |

| 61 | Peninsula vicinity | Camp Manatoc Concord Lodge and Adirondacks Historic District | no public facilities - private property | Truxell Road | 1/10/97 | |

| 62 | Peninsula vicinity | Butler, H. Karl Memorial | no public facilities - private property | Truxell Road | 1/10/97 | |

| 63 | Peninsula vicinity | Camp Manatoc Dining Hall | no public facilities - private property | Truxell Road | 1/10/97 | |

| 64 | Peninsula vicinity | Camp Manatoc Foresters Lodge and Kit Carson/Dan Boone Cabins | no public facilities - private property | Historic District, Truxell Road | 1/10/97 | |

| 65 | Peninsula vicinity | Camp Manatoc Legion Lodge | no public facilities - private property | Truxell Road | 1/10/97 | |

| 66 | Peninsula vicinity | Jyrovat Farmstead | no public facilities | 696 W Streetsboro Road | 5/25/95 | |

| 67 | Sagamore Hills | Lock 34 Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | Highland Rd | 12/17/79 | |

| 68 | Sagamore Hills | Lock 35 Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail | open to the public | Off Ohio State Route 82 | 12/11/79 |

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document "http://www.nps.gov/archive/cuva/planavisit/todo/recreation/ohioerie.htm".

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document "http://www.nps.gov/archive/cuva/planavisit/todo/recreation/ohioerie.htm".

- ↑ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park FACT SHEET" (PDF). NPS. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2015-07-06.

- ↑ "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-06.

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/cuva/learn/nature/mammals.htm

- ↑ "Krejci Dump: A Story of Transformation" National Park Service, Cuyahoga Valley

- ↑ Johnson, Jim: "Generators pay for industrial cleanup" Waste Recycling News, May 13, 2002

- ↑ "Krejci Dump Site Cleanup and Restoration" National Park Service, July 1, 2011

- ↑ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Frequently Asked Questions (U.S. National Park Service)". Nps.gov. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ Rep. Ralph Regula [R-OH16, 1973-2009]. "summary of HR 4578". Govtrack.us. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ "Winter Sports". National Park Service. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ↑ "CVSR". Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad.

- 1 2 3 "Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Ohio & Erie Canal Towpath Trail Tour - Sites to Visit". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Ohio & Erie Canal - Towpath Trail Tour". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "conservancyforcvnp.org". conservancyforcvnp.org. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Cuyahoga Valley National Park". Nps.gov. 2012-04-17. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Stanford House". Day in the Valley.

- 1 2 "Station Road Bridge". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- 1 2 Leverett, Frank (1902). Glacial Formations and Drainage Features of the Erie and Ohio Basins, USGS Monograph Vol. XLI. Washington: US Government Printing Office. p. 216.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cushing, H.P.; Leverett, Frank; Van Horn, Frank (1931). Geology and Mineral Resources of the Cleveland District, Ohio, USGS Bulletin 818. Washington: US Government Printing Office. p. 9,16-19,68-79.

- ↑ Swinford, Edward; Pavey, Richard; Larsen, Glenn (2006). Soller, ed. New Map of the Surficial Geology of the Lorain and Put-in-Bay 30 x 60 Minute Quadrangles, Ohio, in Digital Mapping Techniques '06- Workshop Proceedings. Columbus: USGS Open-File Report 2007-1285 2007. p. 178.

- ↑ Pepper, James; De Witt, Wallace; Demarest, David (1954). Geology of the Bedford Shale and Berea Sandstone in the Appalachian Basin, USGS Professional Paper 259. Washington: US Government Printing Office. pp. 12,70–71.

- ↑ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Visitor Centers". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Canal Visitor Center". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Ohio and Erie Canal". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Interactive Tow-Path Tour". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Frazee House". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Boston Store". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Everett Road Covered Bridge". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Brandywine Village". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2008-06-09.

- ↑ "Happy Days Visitor Center". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Virginia Kendall Unit map". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "The George Stanford House". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places - Cuyahoga Valley National Park". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Hale Farm and Village". Western Reserve Historical Society.

- ↑ "Points of Historic Interest". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places - Cuyahoga Valley National Park". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- ↑ "Brecksville-Northfield High Level Bridge". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ↑ "Tinkers Creek Aqueduct". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

General references

- "A Green Shrouded Miracle: The Administrative History of Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area, Ohio". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- "Ohio and Erie Canal National Heritage Corridor, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- "The Ohio & Erie Canal: Catalyst of Economic Development for Ohio, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- "Cuyahoga Valley National Park - Official Site". National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

- The National Parks: Index 2001–2003. Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior.

Further reading

- Cuyahoga Valley Trails Council (2007). The Trail Guide to Cuyahoga Valley National Park, 3rd Edition, OH: Gray & Company, Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59851-040-9

External links

- Official site: Cuyahoga Valley National Park