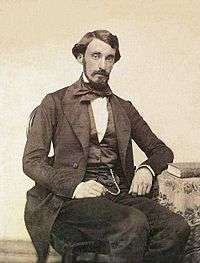

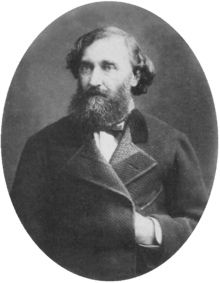

Bartolomé Mitre

| Bartolomé Mitre | |

|---|---|

| |

| 6th President of Argentina | |

|

In office 12 October 1862 – 12 October 1868 Interim: 12 December 1861 – 12 October 1862 | |

| Vice President | Marcos Paz |

| Preceded by | Juan Esteban Pedernera |

| Succeeded by | Domingo Faustino Sarmiento |

| 7th Governor of Buenos Aires | |

|

In office 3 May 1860 – 11 October 1862 | |

| Vice Governor |

Manuel Ocampo Vicente Cazón |

| Preceded by | Felipe Llavallol |

| Succeeded by | Vicente Cazón |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

26 June 1821 Buenos Aires |

| Died |

19 January 1906 (aged 84) Buenos Aires |

| Resting place | La Recoleta Cemetery |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Political party |

Colorado (Uruguay) Unitary (1851–1862) Liberal (1862–1874) National (1874) Civic Union (1890–1891) National Civic Union (1891–1906) |

| Spouse(s) | Delfina Vedia |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Rank |

|

Bartolomé Mitre Martínez (26 June 1821 – 19 January 1906) was an Argentine statesman, military figure, and author. He was the President of Argentina from 1862 to 1868.

Life and times

Mitre was born in Buenos Aires to a Greek family originally named Mitropoulos.

As a liberal, he was an opponent of Juan Manuel de Rosas, and he was forced into exile. He worked as a soldier and journalist in Uruguay as a supporter of General Fructuoso Rivera, who named Mitre Lieutenant Colonel of the Uruguayan Army in 1846. Mitre later lived in Bolivia, Peru, and Chile, and in the latter country, he collaborated with legal scholar and fellow Argentine exile Juan Bautista Alberdi in the latter's periodical, El Comercio of Valparaíso.

Mitre returned to Argentina after the defeat of Rosas at the 1852 Battle of Caseros. He was a leader of the revolt of Buenos Aires against Justo José de Urquiza's federal system, and was appointed to important posts in the provincial government after Buenos Aires seceded from the Confederation.

President of Argentina

The civil war of 1859 resulted in Mitre's defeat by Urquiza at the Battle of Cepeda, in 1860. Issues of customs revenue sharing were settled, and Buenos Aires reentered the Argentine Confederation. Victorious at the 1861 Battle of Pavón, however, Mitre obtained important concessions from the national army, notably the amendment of the Constitution to provide for indirect elections through an electoral college.[1] In October 1862, Mitre was elected president of the republic, and national political unity was finally achieved; a period of internal progress and reform then commenced. During the Paraguayan War, Mitre was initially named the head of the allied forces.

Mitre was also the founder of La Nación, one of South America's leading newspapers, in 1870. His opposition to Autonomist Party nominee Adolfo Alsina, whom he viewed as a veiled Buenos Aires separatist, led Mitre to run for the presidency again, though the seasoned Alsina outmaneuvered him by fielding Nicolás Avellaneda, a moderate lawyer from remote Catamarca Province. The electoral college met on 12 April 1874, and awarded Mitre only three provinces, including Buenos Aires.

Mitre took up arms again. Hoping to prevent Avellaneda's 12 October inaugural, he mutineered a gunboat; he was defeated, however, and only President Avellaneda's commutation spared his life.[2] Following the 1890 Revolution of the Park, he broke with the conservative National Autonomist Party PAN) and co-founded the Civic Union with reformist Leandro Alem. Mitre's desire to maintain an understanding with the ruling PAN led to the Civic Union's schism in 1891, upon which Mitre founded the National Civic Union, and Alem, the Radical Civic Union (the oldest existing party in Argentina).

He dedicated much of his time in later years to writing. According to some of his critics, as a historian Mitre took several questionable actions, often ignoring key documents and events on purpose in his writings. This caused his student Adolfo Saldías to distance himself from him, and for future revisionist historians such as José María Rosa to question the validity of his work altogether. He also wrote poetry and fiction (Soledad: novela original), and translated Dante's La divina commedia (The Divine Comedy) into Spanish. He was also an active freemason,[3] and the grandfather of poet, Margarita Abella Caprile.

On his death in 1906, he was interred in La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires. 19 January 2006 marked the centenary of Mitre's death.

Bibliography

Mitre ranks as an important South-American historiographer. He wrote the best accounts of South America's wars of independence and published many works, amongst which are:

- Historia de Belgrano y de la independencia argentina ["History of Belgrano and of the argentine independence"] (1857; fifth edition, four volumes, 1902)

- Historia de San Martín y de la emancipación sudamericana ["History of San Martín"] (1869; third edition, six volumes, 1907)

- Rimas ["Rimes"] (new edition, 1890)

- Ulrich Schmidl, primer historiador del Rio de la Plata ["Ulrich Schmidl, first historian of the Rio de la Plata"] (1890)

There is an abridged translation of the Historia de San Martín, entitled The Emancipation of South America (London, 1893) by W. Pilling. Mitre's speeches were collected as Arengas (third edition, three volumes, 1902).

References

- J. J. Biedma, El Teniente General Bartolomé Mitre, in Bartolomé Mitre, Arengas, volume iii (Buenos Aires, 1902).

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of Argentina. London: Scarecrow Press, 1978.

- ↑ Todo Argentina: 1874 (Spanish)

- ↑

William H. Katra, The Argentine Generation of 1837: Echeverría, Alberdi, Sarmiento, Mitre (Madison, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1996).

External links

- Works by Bartolomé Mitre at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Bartolomé Mitre at Internet Archive

- Works by Bartolomé Mitre at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Juan E. Pedernera |

President of Argentina 1862–1868 |

Succeeded by Domingo F. Sarmiento |