3,4-Diaminopyridine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Firdapse |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | UK Drug Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | N07XX05 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 93–100%[1][2] |

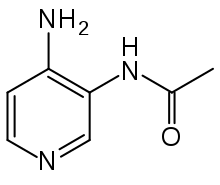

| Metabolism | Acetylation to 3-N-acetylamifampridine |

| Biological half-life |

2.5 hrs (amifampridine) 4 hrs (3-N-acetylamifampridine) |

| Excretion | Renal (19% unmetabolized, 74–81% 3-N-acetylamifampridine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

54-96-6 |

| PubChem (CID) | 5918 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 8032 |

| ChemSpider |

5705 |

| UNII |

RU4S6E2G0J |

| KEGG |

D10228 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL354077 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C5H7N3 |

| Molar mass | 109.13 g·mol−1 |

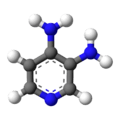

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| Melting point | 218 to 220 °C (424 to 428 °F) decomposes |

| Solubility in water | 24 mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

| | |

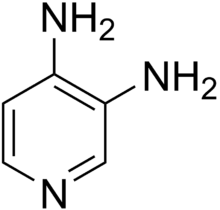

3,4-Diaminopyridine (or 3,4-DAP) is an organic compound with the formula C5H3N(NH2)2. It is formally derived from pyridine by substitution of the 3 and 4 positions with an amino group.

The compound 3,4-diaminopyridine has the International Nonproprietary Name amifampridine and is used as a drug, predominantly in the treatment of a number of rare muscle diseases. The phosphate salt of amifampridine is a more stable formulation that does not require refrigeration; it is marketed in the EU by BioMarin Pharmaceutical under the trade name Firdapse and designated as an orphan drug in the EU [3] and in the United States.[4] In the United States, amifampridine phosphate is under investigation for the treatment of Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) and congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS) by Catalyst Pharmaceuticals,[5][6] and was granted a breakthrough therapy designation by the FDA in 2013 for LEMS.[7][8] In a Phase 3 clinical trial, it demonstrated superiority over placebo in both co-primary endpoints.[9][10][11] LEMS patients can receive amifampridine phosphate at no cost under an ongoing expanded access program.[12][13] A study to develop patient entry criteria for a clinical trial of the free base form of amifampridine has also been completed by Jacobus Pharmaceutical Company.[14] This form remains available at no cost to patients with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome and congenital myasthenic syndromes under a long-standing compassionate use program, with FDA oversight, from Jacobus Pharmaceutical Company (see also Medical uses and Economics, below).

Medical uses

A 2011 systematic review from the Cochrane Collaboration found data favoring its use in LEMS.[15] Although not approved for pharmaceutical use in the United States, amifampridine is available under compassionate use regulations for the treatment of LEMS.

Amifampridine is also used to treat many of the congenital myasthenic syndromes, particularly those with defects in choline acetyltransferase, downstream kinase 7, and those where any kind of defect causes "fast channel" behaviour of the acetylcholine receptor.[16] In the US, amifampridine is under development as an orphan drug for congenital myasthenic syndrome[17] and 3,4-diaminopyridine is available at no cost for patients with congenital myasthenic syndromes under a long-standing compassionate use program from Jacobus Pharmaceutical Co. Additionally in the US, amifampridine phosphate is available at no cost to CMS patients in Catalyst Pharmaceuticals Expanded Access Program.

Amifampridine has also been proposed for the treatment of multiple sclerosis, but a 2002 systematic review found that there was little unbiased data to support its use in MS.[18]

Contraindications

As amifampridine prolongs QT time, it is contraindicated in patients with congenital long QT syndrome and in patients that already take one or more QT prolonging drugs such as sultopride, disopyramide, cisapride, domperidone, rifampicin or ketoconazol. It is also contraindicated in patients with epilepsy or badly controlled asthma.[2]

Adverse effects

Little is known about side effects because the drug is only used for rare diseases. Reported side effects include paraesthesia (tingling or prickling sensations) and hypoaesthesia (numbness), especially periorally (around the mouth), as well as gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea and diarrhoea.[2]

Interactions

No systematic interaction studies have been conducted. Based on theoretic reasoning, other QT prolonging drugs may increase the risk of long QT syndrome and torsades de pointes (see contraindications above). Other drugs that lower the seizure threshold may increase the risk of seizures. Interactions via the liver's cytochrome P450 enzyme system are considered unlikely.[2]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

In Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome, acetylcholine release is inhibited as antibodies involved in the host response against certain cancers cross-react with Ca2+ channels on the prejunctional membrane. Amifampridine works by blocking potassium channel efflux in nerve terminals so that action potential duration is increased.[19] Ca2+ channels can then be open for a longer time and allow greater acetylcholine release to stimulate muscle at the end plate.

Pharmacokinetics

Amifampridine is quickly and almost completely (93–100%) absorbed from the gut. In a study with 91 healthy subjects, maximum amifampridine concentrations in blood plasma were reached after 0.6 (±0.25) hours when taken without food, or after 1.3 (±0.9) hours after a fatty meal, meaning that the speed of absorption varies widely. Biological half-life (2.5±0.7 hrs) and the area under the curve (AUC = 117±77 ng∙h/ml) also vary widely between subjects, but are nearly independent of food intake.[2]

The substance is deactivated by acetylation via N-acetyltransferases to the single metabolite 3-N-acetylamifampridine. Activity of these enzymes (primarily N-acetyltransferase 2) in different individuals seems to be primarily responsible for the mentioned differences in half-life and AUC: the latter is increased up to 9-fold in slow metabolizers as compared to fast metabolizers.[2]

Amifampridine is eliminated via the kidneys and urine to 74–81% as N-acetylamifampridine and to 19% in unchanged form.[2]

Chemistry

3,4-Diaminopyridine is a pale yellow to pale brown crystalline powder that melts at about 218–220 °C (424–428 °F) under decomposition. It is readily soluble in methanol, ethanol and hot water, but only slightly in diethyl ether.[20][21] Solubility in water at 20 °C (68 °F) is 25 g/L.

The drug formulation amifampridine phosphate contains the phosphate salt, more specifically 4-aminopyridine-3-ylammonium dihydrogen phosphate.[21] This salt forms prismatic, monoclinic crystals (space group C2/c)[22] and is readily soluble in water.[23]

Society and culture

Economics

The licensing of Firdapse in 2010 in Europe led to a sharp increase in price for the drug. In some cases, this has led to hospitals using an unlicensed form rather than the licensed agent, as the price difference proved prohibitive. BioMarin has been criticized for licensing the drug on the basis of previously conducted research, and yet charging exorbitantly for it.[24] A group of UK neurologists and pediatricians petitioned to prime minister David Cameron in an open letter to review the situation.[25] The company responded that it submitted the licensing request at the suggestion of the French government, and points out that the increased cost of a licensed drug also means that it is monitored by regulatory authorities (e.g. for uncommon side effects), a process that was previously not present in Europe.[26]

Availability

In the United States, both the phosphate and the free base have completed clinical trials to treat LEMS.[27][28][29] Both formulations are available to LEMS patients in the U.S.: the free base is available to patients with LEMS and congenital myasthenic syndromes under a compassionate distribution program by Jacobus Pharmaceutical Company, and the phosphate salt is available to LEMS and CMS patients under an expanded access program by Catalyst Pharmaceuticals. Patients must be diagnosed with LEMS or congenital myasthenic syndrome and meet appropriate inclusion criteria.[12]

Compounding pharmacies may also be a source of amifampridine in the U.S. In Europe, the phosphate is sold by BioMarin, and the free base is compounded, usually by hospital pharmacies.

See also

References

- ↑ "Firdapse. Summary of product characteristics" (PDF). EMA. 7 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jasek, W, ed. (2015). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag.

- ↑ "Firdapse". European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- ↑ https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/opdlisting/oopd/detailedIndex.cfm?cfgridkey=295309

- ↑ Baker DE (Nov 2013). "Breakthrough Drug Approval Process and Postmarketing ADR Reporting". Hospital Pharmacy. 48 (10): 796–8. doi:10.1310/hpj4810-796. PMID 24421428.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT00265148 for "A Phase 3 Study of Amifampridine Phosphate in Patients With Lambert Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome (LEMS)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ "Rare Disease: Catalyst Pharmaceutical Receives 20th FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designation". Orphan Druganaut Blog. 2013-08-27.

- ↑ Bandell B (2013-08-28). "Shares of Catalyst Pharmaceuticals soar 42% on FDA news". South Florida Business Journal.

- ↑ American Neurological Association 2013 Meeting Poster ID: S737WIP

- ↑ "Special Issue: 2014 Annual Meetings". Annals of Neurology. 76 (S18): i–ii, S1–S254. October 2014. doi:10.1002/ana.v76.S18.

- ↑ Muscular Dystrophy Association Press Release

- 1 2 Clinical trial number NCT02189720 for "Expanded Access Study of Amifampridine Phosphate in LEMS, Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome, or Downbeat Nystagmus Patients (EAP-001)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ Radke J (2014-10-30). "Catalyst Using the Expanded Access Program to Conduct Phase IV Study with LEMS Patients". Rare Disease Report.

- ↑ Sanders D, Jacobus L, Ales K, Jacobus D (6 April 2015). "Predicting Responsiveness to Study Drug Before Randomization in the DAPPER Trial of 3,4-Diaminopyridine (3,4-DAP) in Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome (LEMS)". Neurology. 84 (14). Supplement P7.066.

- ↑ Keogh M, Sedehizadeh S, Maddison P (2011). "Treatment for Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD003279. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003279.pub3. PMID 21328260.

- ↑ Argov Z (Oct 2009). "Management of myasthenic conditions: nonimmune issues". Current Opinion in Neurology. 22 (5): 493–7. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32832f15fa. PMID 19593127.

- ↑ Archived May 21, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Solari A, Uitdehaag B, Giuliani G, Pucci E, Taus C (2002). Solari A, ed. "Aminopyridines for symptomatic treatment in multiple sclerosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD001330. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001330. PMID 11687106.

- ↑ Kirsch GE, Narahashi T (June 1978). "3,4-diaminopyridine. A potent new potassium channel blocker". Biophys J. 22 (3): 507–12. doi:10.1016/s0006-3495(78)85503-9. PMC 1473482

. PMID 667299.

. PMID 667299. - ↑ "Diaminopyridine (3,4-)" (PDF). FDA. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- 1 2 Dinnendahl, V; Fricke, U, eds. (2015). Arzneistoff-Profile (in German). 1 (28th ed.). Eschborn, Germany: Govi Pharmazeutischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7741-9846-3.

- ↑ "Crystal Structure and Solid-State Properties of 3,4-Diaminopyridine Dihydrogen Phosphate and Their Comparison with Other Diaminopyridine Salts". Cryst Growth Des. 13 (2): 708–715. 2013. doi:10.1021/cg3014249.

- ↑ A. Klement (9 November 2015). "Firdapse". Österreichische Apothekerzeitung (in German) (23/2015): 10f.

- ↑ Daniel Martin (2010-09-27). "Hospitals are forced to use unlicensed medicines to save millions". Daily Mail. Archived from the original on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- ↑ Nicholl DJ, Hilton-Jones D, Palace J, Richmond S, Finlayson S, Winer J, Weir A, Maddison P, Fletcher N, Sussman J, Silver N, Nixon J, Kullmann D, Embleton N, Beeson D, Farrugia ME, Hill M, McDermott C, Llewelyn G, Leonard J, Morris M (2010). "Open letter to prime minister David Cameron and health secretary Andrew Lansley". BMJ. 341: c6466. doi:10.1136/bmj.c6466. PMID 21081599.

- ↑ Hawkes N, Cohen D (2010). "What makes an orphan drug?". BMJ. 341: c6459. doi:10.1136/bmj.c6459. PMID 21081607.

- ↑ Shin O, Gorodetzky C, Winship D (6 April 2015). "Amifampridine phosphate (Firdapse) is safe and effective in a pivotal Phase 3 trial in LEMS patients". 84 (14). Supplement PL2.001.

- ↑ Raust, JA; et al. (2007). "Stability studies of ionised and non-ionised 3,4-diaminopyridine: hypothesis of degradation pathways and chemical structure of degradation products". J Pharm Biomed Anal. 43 (1): 83–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2006.06.007. PMID 16844337.

- ↑ "Assessment report for Zenas" (PDF). EMA. 2009.