Azimilide

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code | none |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

149908-53-2 |

| PubChem (CID) | 9571004 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 2588 |

| ChemSpider |

7845470 |

| UNII |

74QU6P2934 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL123558 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C23H28ClN5O3 |

| Molar mass | 457.953 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

Azimilide is a class ΙΙΙ antiarrhythmic drug (used to control abnormal heart rhythms). The agents from this heterogeneous group have an effect on the repolarization, they prolong the duration of the action potential and the refractory period. Also they slow down the spontaneous discharge frequency of automatic pacemakers by depressing the slope of diastolic depolarization. They shift the threshold towards zero or hyperpolarize the membrane potential. Although each agent has its own properties and will have thus a different function.

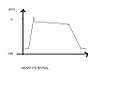

Heart potential

Azimilide dihydrochloride is a chlorophenylfuranyl compound, which slows repolarization of the heart and prolongs the QT interval of the electrocardiogram. Prolongation of atrial or ventricular repolarization can provide an anti-arrhythmic benefit in patients with heart rhythm disturbances, and this has been the primary interest in the clinical development azimilide. In rare cases, excessive prolongation of ventricular repolarization by azimilide can result in predisposition towards severe ventricular arrhythmias. Most recent clinical trials have investigated the use of azimilide in reducing the frequency and severity of arrhythmias in patients with implanted cardiac pacemakers-defibrillators, where rare pro-arrhythmic events are rescued by the device.

The ion currents

The action of azimilide is directed to the different currents present in atrial and ventricular cardiac myocytes. It principally blocks IKr, and IKs, with much weaker effects on INa, ICa, INCX and IK.Ach. The IKr(rapid)and IKs (slow) are inward rectifier potassium currents, responsible for repolarizing cardiac myocytes towards the end of the cardiac action potential. A somewhat higher concentration of azimilide is needed to block the IKs current. Both blockages result in an increase of the QT interval and a prolongation of atrial and ventricular refractory periods.

Azimilide blocks hERG channels (which encode the IKr current) with an affinity comparable to that with which KvLQT1 / minK channels (which encode the IKs current) are blocked. This block exhibits reverse use-dependence, i.e. the channel blocking effect wanes at faster pulsing rates of the cell. A possible explanation is an interaction of azimilide with K+ close to its binding site in the ion channel. However, there is an agonist effect as well, which is a voltage-dependent effect. This is a dual effect, a low voltage depolarization near the activation threshold will increase the current amplitude and higher depolarizing voltages will suppress the current amplitude. The effect comes from outside of the cell membrane and does not depend on G-proteins or kinase activity inside the cell. Azimilide binds on the extracellular domain of the hERG channel, this propagates a conformational change and inhbits the current. This change makes the activation gate open more easily by low voltage depolarization. Azimilide has two separate binding sites in hERG channel, one for its antagonist function and the other for the agonist function.

Pharmacology

Azimilide has been studied for its anti-arrhythmic effects: its converts and maintains sinus rhythm in patients with atrial arrhythmias; and it reduces the frequency and severity of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with implanted cardioverter-defibrillators. Azimilide's most important adverse effect is torsades de pointes, which is a form of ventricular tachycardia.

Pharmacokinetics

The drug is administered orally and will be completely absorbed. It shows none or very minor interactions with other drugs and it will be eventually cleared by the kidney. A peak in concentration in the blood is observed seven hours after the administration of Azimilide. The metabolic clearance is mediated through several pathways:

- 10% is found unchanged in the blood

- 30% will cleared by cleavage

- 25% by CYP 1A1 pathway

- 25% by CYP 3A4

F-1292 is the major metabolite of azimilide, it is formed cleavage of the aromethine bond. Unlike desmethyl azimilide, azimilide N-oxide and azimilide carboxylate F-1292 has no cardiovascular activity while the other three minor metabolites have a class ΙΙΙ antiarrhythmic activity. They only make out 10% of azimilde in the blood, so their contribution is not measurable.

This use of azimilide is very controversial subject, but this article will give only the plain scientific information about this drug.

References

- Nishida A., Reien Y., Ogura T., Uemura H., Tamagawa M., Yabana H., Nakaya H.(2007). Effects of azimilide on the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-operated K+current and experimental atrial fibrillation in guinea-pig hearts. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 105,229-239<k />

- Watanabe Y., Koide Y., Kimura J. (2006). Topics on the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger:Pharmacological characterization of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger inhibitors. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences102,7-16<k />

- Hanna I., Langberg J. (2004). The shocking story of azimilide. Journal of the American Heart Association110,3624-3626<k />

- Lombardi F., Borggrefe M., Ruzyllo W., Lüderitz B. (2006). Azimilide vs. placebo and sotalol for persistent atrial fibrillation:the A-COMET-2 trial. European Heart Journal27,2224-2231<k />

- Braunwald E., Zipes P., Libby P.(2001) Heart Disease A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine 6th edition. W.B. Saunders Company 717-736, ISBN 0-7216-8561-7.

- Busch A., Eigenberger B., Jurkiewicz N., Salata J., Pica A., Suessbrich H., Lang F. (1998). Blockage of HERG channels by the class ΙΙΙ antiarrhythmic azimilide:mode of action. British Journal of Pharmacology123,23-30<k />

- Jiang M., Dun W., Fan J.-S., Tseng G.-N. (1999). Use-Dependent 'Agonist' Effect of Azimilide on the HERG Channels. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics291,1324-1336<k />

- Corey A., Agnew J., Valentine S., Parekh N., Powell J., Thompson G. (2002). The British Journal of Pharmacology54,449-452<k />