American ethnicity

.jpg) Theodore Roosevelt believed a distinct American race had been formed on the frontier. He equated Americanization with ethnic assimilation and spoke out against hyphenated Americans.[1] | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

(20,875,080[2] 6.75% of the US population in 2012) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Southern United States and Midwestern United States | |

| Languages | |

| English (American English dialects) | |

| Religion | |

|

Protestantism (Southern Baptist, Methodist, Evangelical Christian, etc.) Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Anglo-Americans; English Americans; European Americans; Confederados; Canadians; British; Australians; New Zealanders; Rhodesians; British diaspora in Africa; Dutch; Germans; other Germanic people |

Americans are a North American ethnic group descended primarily from pre-revolution colonialists in the American Thirteen Colonies, most of which were English and Scotch-Irish with amounts of French, Dutch, Swedish, Welsh, and German. [3][4][5] They generally dominated the culture and government of the United States until the later part of the twentieth century. Their primary language is American English, a distinct variety that traces to the English of the British Empire with various loanwords from native languages and other colonial languages, notably Spanish. American, as an ethnic term, has been hard to distinguish with many preferring to use hyphenated American names, using American only as a nationality. Because of this inconsistency, it is difficult to estimate the actual number of ethnic Americans. Americans make up anywhere from 7.2% to 23.3% of the United States population, possibly more. These statistics are from census data, which has its own margin of error. American ethnic identity is most commonly reported in the Southern United States, particularly in the Upper South.[6]

History

The emergence of a distinct American ethnic identity in the Thirteen Colonies mirrors that of the Criollo people in Spanish America, or the Afrikaner people in the Dutch Cape Colony. In the War of Jenkins Ear, 1741, local militiamen fighting under Vice-Admiral Edward Vernon were the first to be called "Americans" rather than "colonials" or "colonists".[7]

President Theodore Roosevelt, a prominent naturalist, believed a distinct American ethnic group had been formed on the frontier,[1] though his beliefs certainly weren't unique in the 19th and 20th centuries. Many famous Americans, like Thomas Jefferson, Sam Houston, J. D. B. De Bow, J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Frederick Jackson Turner, all prescribed to the belief that Americans were a distinct ethnic identity, although their beliefs varied in different ways.[8][9][10][11]

J.D.B DeBow, a well known Southron intellectual and Fire Eater, believed that the Southern people were inherently superior due to their descent from the Normans and other peoples of Roman descent, such as the Huguenots. DeBow wrote extensively on his belief that the Yankees were a lesser race, as they were descended from Germanic peoples, whom DeBow considered to be barbarous.[8] A few of his fellow Fire-Eaters also held similar beliefs, some more radical than his own.

Today, people in the US who identify as ethnically American tend to have long genealogical histories within the country reaching back many generations to colonial-era immigration. Ethnic "Americans" share most of their ancestry with modern-day British, Dutch, German, Irish and French Americans, as well as with Melungeons in the Appalachian region.

American ancestry in the U.S. Census

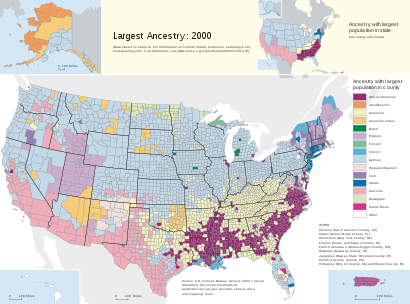

According to 2000 U.S census data, an increasing number of United States citizens identify simply as Americans on the question of ancestry.[12][13][14] According to the United States Census Bureau, the number of people in the United States who reported American and no other ancestry increased from 12.4 million in 1990 to 20.2 million in 2000.[15] This increase represents the largest numerical growth of any ethnic group in the United States during the 1990s.[16] The U.S. Census Bureau says, "Ancestry refers to a person's ethnic origin or descent, 'roots,' or heritage, or the place of birth of the person or the person's parents or ancestors before their arrival in the United States".[17] American sociologist Mary C. Waters suggests that it may be speculated that mixed ethnicity or ancestry nominate a more recent and differentiated ethnic group.[18]

In the 2000 United States Census, 7.2 percent of the American population chose to identify itself as having American ancestry (see Race and ethnicity in the United States for a list of ancestries in the U.S.).[16] The four states in which a plurality of the population reported American ancestry are Arkansas (15.7%), Kentucky (20.7%), Tennessee (17.3%), and West Virginia (18.7%).[15] Sizable percentages of the populations of Alabama (16.8%), Mississippi (14.0%), North Carolina (13.7%), South Carolina (13.7%), Georgia (13.3%), and Indiana (11.8%) also reported American ancestry. In the Southern United States as a whole 11.2% reported American ancestry, second only to African American. American was the 4th most common ancestry reported in the Midwest (6.5%) and West (4.1%). All Southern states except for Delaware and Maryland reported at or above the national average of 7.2% American, but outside the South, only Missouri, Indiana, Ohio, Idaho, Maine. All Southern states except for Delaware, Maryland, Florida, and Texas reported 10% or more American, but outside the South, only Missouri and Indiana did so. American was in the top 5 ancestries reported in all Southern states except for Delaware, in 4 Midwestern states bordering the South (Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio) as well as Iowa, and 6 Northwestern states (Colorado, Idaho, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming), but only one Northeastern state, Maine. The pattern of areas with high levels of American is similar to that of areas with high levels of not reporting any national ancestry.[19]

| South | Midwest | West | NE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 11.2% | 6.5% | 4.1% | |

| Plurality | AR KY TN WV | |||

| 10%+ | All but DE MD FL TX | IN MO | ||

| 7.2%+ | All but DE MD | IN MO OH | ME | |

| Top 5 | All but DE | IN MO OH KS IA | CO ID OR UT WA WY | ME |

In 2011, 20,875,080, 6.75% of the total estimated population, self-identified as having American ethnicity in the 2009–2011 American Community Survey.[2]

The long form decennial census questionnaire was replaced by the annual American Community Survey in 2005 which has a smaller sample size. The ancestry question is largely similar to the 2000 long form census.

See also

- American (word)

- American exceptionalism

- Americans

- Nativism (politics)

- Race and ethnicity in the United States

- Old Stock Americans

References

- Notes

- 1 2 Dyer, Thomas G. (1980). Theodore Roosevelt and the Idea of Race. LSU Press. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- 1 2 "B04006, People Reporting Ancestry". 2009-2011 American Community Survey. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ↑ Walker, Jessica Lorraine (2007). Our Anglo-Saxon ancestors : Thomas Jefferson and the role of English history in the Building of the American Nation. Australia: The University of Western Australia. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ Di Leo, John F. "To Retain the Rights of Englishmen". Illinois Review. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ Fischer, David Hackett (March 14, 1989). Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ Ancestry: 2000 2004, p. 6

- ↑ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1972). The Oxford History of the American People. New York City: Mentor. p. 216. ISBN 0-451-62600-1.

- 1 2 DeBow, James Dunwoody Brownson. "Debow's review, Agricultural, commercial, industrial progress and resources.". Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ↑ Johnson, Adam. "Notes from Youville: The Great American Melting Pot". Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ↑ Goldman, Samuel. "Do We Have an Anglo-Saxon Heritage?". Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ↑ Houston, Sam. "Civil War Quotes". Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ↑ Reynolds Farley, 'The New Census Question about Ancestry: What Did It Tell Us?', Demography, Vol. 28, No. 3 (August 1991), pp. 414, 421.

- ↑ Stanley Lieberson and Lawrence Santi, 'The Use of Nativity Data to Estimate Ethnic Characteristics and Patterns', Social Science Research, Vol. 14, No. 1 (1985), pp. 44–46.

- ↑ Stanley Lieberson and Mary C. Waters, 'Ethnic Groups in Flux: The Changing Ethnic Responses of American Whites', Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 487, No. 79 (September 1986), pp. 82–86.

- 1 2 Ancestry: 2000 2004, p. 7

- 1 2 Ancestry: 2000 2004, p. 3

- ↑ Ancestry, U.S. Census Bureau.

- ↑ Waters, Mary C. (1990). Ethnic Options: Choosing Identities in America. University of California Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-520-07083-7.

- ↑ http://www.census.gov/population/www/cen2000/censusatlas/pdf/9_Ancestry.pdf p. 155 (end)

- Bibliography

- "Ancestry: 2000 (Census 2000 Brief)" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. June 2004.

- Reynolds Farley (August 1991). "The New Census Question about Ancestry: What Did It Tell Us?". Demography. 28 (3): 411–429. doi:10.2307/2061465. PMID 1936376. Archived from the original on July 16, 2009.