Melungeon

|

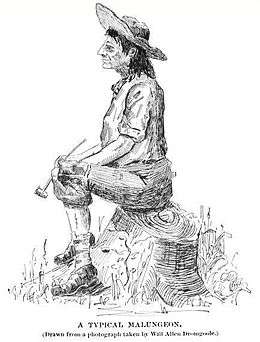

Will Allen Dromgoole's drawing of a Melungeon at Newman's Ridge, Tennessee, c. 1890 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (Unknown) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Originally in the vicinity of Cumberland Gap (East Tennessee and Eastern Kentucky; later migrations throughout the United States) | |

| Languages | |

| English | |

| Religion | |

| Baptist; other | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Redbones, Carmel Indians |

Melungeon (/məˈlʌndʒən/ mə-LUN-jən) is a term traditionally applied to one of numerous "tri-racial isolate" groups of the Southeastern United States. Historically, Melungeons were associated with the Cumberland Gap area of central Appalachia, which includes portions of East Tennessee, Southwest Virginia, and eastern Kentucky. Tri-racial describes populations thought to be of mixed European, African and Native American ancestry. Although there is no consensus on how many such groups exist, estimates range as high as 200.[1][2] Melungeons were often referred to by other settlers as "Turks", "Moors" or "Portuguese".

According to the Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, in his 1950 dissertation, cultural geographer Edward Price proposed that Melungeons were families descended from free people of color (who were likely of both European and African ancestry) and mixed-race unions between persons of African ancestry and Native Americans in colonial Virginia.[3]

Definition

The ancestry and identity of Melungeons has been a highly controversial subject.[4] Secondary sources disagree as to their ethnic, linguistic, cultural, and geographic origins and identity, as they are of mixed racial ancestry. They might accurately be described as a loose collection of families of diverse origins who migrated, settled near each other, and intermarried, mostly in Hancock and Hawkins counties in Tennessee, nearby areas of Kentucky, and in Lee County, Virginia.[5] Their ancestors can usually be traced back to colonial Virginia and the Carolinas. They were largely endogamous, marrying primarily within their community until about 1900.

Melungeons have been defined as having multiracial ancestry. They did not exhibit characteristics that could be classified as those of a single racial phenotype. Most modern-day descendants of Appalachian families traditionally regarded as Melungeon are generally European American in appearance, often (though not always) with dark hair and eyes, and a swarthy or olive complexion.[6] Descriptions of Melungeons have varied widely over time; in the 19th and early 20th century, they were sometimes identified as "Portuguese," "Native American," or "light-skinned African American". During the nineteenth century, free people of color sometimes identified as Portuguese or Native American in order to avoid being classified as black in the segregated slave societies.[7] Other Melungeon individuals and families are accepted and identify as white, particularly since the mid-20th century. They have tended to "marry white" since before the twentieth century.[8]

Scholars and commentators do not agree on who should be included under the term Melungeon. Contemporary authors identify differing lists of surnames to be included as families associated with Melungeons. The English surname Gibson and Irish surname Collins appear frequently; genealogist Pat Elder calls them "core" surnames.[9] Vardy Collins and Shep Gibson had settled in Hancock County, and they and other Melungeons are documented by land deeds, slave sales and marriage licenses.[6] Other researchers include the surnames Powell, LeBon, Bolling, Bunch, Goins, Goodman, Heard, Minor, Mise, Mullins, and several others. (Family lines have to be researched individually, as not all families with these surnames are Melungeon.) As with many other surname groups, not all families with each surname have the same racial background and ancestry.

The original meaning of the word "Melungeon" is obscure (see Etymology below). From about the mid-19th to the late 20th centuries, it referred exclusively to one tri-racial isolate group, the descendants of the multiracial Collins, Gibson, and several other related families at Newman's Ridge, Vardy Valley, and other settlements in and around Hancock and Hawkins counties, Tennessee.[5]

Origins

According to the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, which Virginia incorporated into law in 1662, children were assigned the social status and ethnicity of their mother, regardless of their father's ethnicity or citizenship. This meant the children of African slave mothers were born into slavery. But it also meant the children of free white or mulatto women, even if fathered by enslaved African men, were born free. The free descendants of such unions formed many of the oldest free families of color. Early colonial Virginia was very much a "melting pot" of peoples, and some of these early multiracial families were ancestors of the later Melungeons. Each family line has to be traced separately. Over the generations, most individuals of the group called Melungeon were actually people of European and African descent, whose ancestors had been free in colonial Virginia.[8]

Edward Price's dissertation on "Mixed-Blood Populations of the Eastern United States as to Origins, Localizations, and Persistence" stated that children of European and free black unions had intermarried with persons of Native American ancestry. These conclusions have been largely upheld in subsequent scholarly and genealogical studies. In 1894, the U.S. Department of the Interior, in its "Report of Indians Taxed and Not Taxed," noted that the Melungeons in Hawkins County "claim to be Cherokee of mixed blood".[3] The term Melungeon has since sometimes been applied as a catch-all phrase for a number of groups of mixed-race ancestry. In 2012, the genealogist Roberta Estes and her fellow researchers reported that the Melungeon lines likely originated in the unions of black and white indentured servants living in Virginia in the mid-1600s before slavery became widespread.[5] They concluded that as laws were put in place to prevent the mixing of races, the family groups could only intermarry with each other. They migrated together from western Virginia through the Piedmont frontier of North Carolina, before settling primarily in the mountains of East Tennessee.[10]

Evidence

Free people of color are documented as migrating with European-American neighbors in the first half of the 18th century to the frontiers of Virginia and North Carolina, where they received land grants like their neighbors. For instance, the Collins, Gibson, and Ridley (Riddle) families owned land adjacent to one another in Orange County, North Carolina, where they and the Bunch family were listed in 1755 as "free Molatas (mulattoes)", subject to taxation on tithes. By settling in frontier areas, free people of color found more amenable living conditions and could escape some of the racial strictures of the Virginia and North Carolina Tidewater plantation areas.[5][11]

Historian Jack D. Forbes has discussed laws in South Carolina related to racial classification:

In 1719, South Carolina decided who should be an "Indian" for tax purposes since American [Indian] slaves were taxed at a lesser rate than African slaves. The act stated: "And for preventing all doubts and scruples that may arise what ought to be rated on mustees, mulattoes, etc. all such slaves as are not entirely Indian shall be accounted as negro.[12]

Forbes found this to be significant, as he said at the time, "mustees" and "mulattoes" were considered persons of part Native American ancestry. He wrote,

My judgment (to be discussed later) is that a mustee was primarily part-African and American [Indian] and that a mulatto was usually part-European and American [Indian]. The act is also significant because it asserts that part-American [Indians] with or without [emphasis added] African ancestry could be counted as Negroes, thus having an implication for all later slave censuses.[12]

Beginning about 1767, some of the ancestors of the Melungeons reached the frontier New River area, where they are listed on tax lists of Montgomery County, Virginia, in the 1780s. From there they migrated south in the Appalachian Range to Wilkes County, North Carolina, where some are listed as "white" on the 1790 census. They resided in a part which became Ashe County, where they are designated as "other free" in 1800.[13]

The Collins and Gibson families (identified as Melungeon ancestors) were recorded in 1813 as members of the Stony Creek Primitive Baptist Church in Scott County, Virginia, where they appear to have been treated as social equals of the white members. The earliest documented use of the term "Melungeon" is found in the minutes of this church (see Etymology below). While there are historical references to the documents, the evidence has come from transcribed copies.[5]

From the Virginia and North Carolina frontiers, the families migrated west into Tennessee and Kentucky. The earliest known Melungeon in what is now northeast Tennessee was Millington Collins, who executed a deed in Hawkins County in 1802. However, there is some evidence that Vardy Collins and Shep Gibson had settled in Hawkins (what is now Hancock County) by 1790.[6] Several Collins and Gibson households were listed in Floyd County, Kentucky in the 1820 census, where they were classified as "free persons of color". On the 1830 censuses of Hawkins and neighboring Grainger County, Tennessee, the Collins and Gibson families are listed as "free-colored". Melungeons were residents of the part of Hawkins that in 1844 was organized as Hancock County.[14]

By 1830, the Melungeon community in Hawkins County numbered 330 people in 55 families; in adjoining Grainger County, there were 130 people in 24 families. "Because of them, Hawkins County had more free colored persons in the 1830 census than any other county in Tennessee except Davidson (which includes Nashville) and more free colored families named Collins than any other county in the United States."[13] Melungeon families have also been traced in Ashe County in northwestern North Carolina.[13]

Contemporary accounts documented that Melungeon ancestors were considered to be mixed race by appearance. During the 18th and early 19th centuries, census enumerators designated them as "mulatto", "other free", or as "free persons of color". Sometimes they were listed as "white", sometimes as "black" or "negro", but almost never as "Indian". One family described as "Indian" was the Ridley (Riddle) family, noted as such on a 1767 Pittsylvania County, Virginia, tax list.[15] They had been designated as "mulattoes" in an earlier record of 1755.[16] Estes et al., in their 2012 summary of the Melungeon Core DNA Testing Program, documented that the Riddle family is one of two of the identified Melungeon participants to have historically verifiable Native American origins.[5]

The court record of Jacob Perkins vs John White (1858) in Johnson County, Tennessee, provides definitions of the time related to race and free people of color. At the time, as in Virginia, if a free person was mostly white (one-eighth or less black), he was considered legally white and a citizen of the state:

Persons that are known and recognized by the Constitution and laws of Tennessee, as free persons of color are those who by the act of 1794 section 32 are taken and deemed to be capable in law to be certified in any case what is in, except against each other or in the language of the statute "all Negroes, Indians, Mulattoes, and all persons of mixed blood descended from Negro or Indian ancestors to the third generation inclusive though one ancestor of each generation may have been a white person, white bond or free." ... That if the great grandfather of Plaintiff was an Indian or Negro and he is descended on the mother's side from a white woman, without any further Negro or Indian blood than such as he derived on the father's side, then the Plaintiff is not of mix blood, or within the third generation inclusive; in other words that if the Plaintiff has not in his veins more than 1/8 of Negro or Indian blood, he is a citizen of this state and it would be slanderous to call him a Negro.[17]

During the 19th century, due to their intermarriage with white families, Melungeon-surnamed families began to be classified as white on census records with increasing frequency.[8] In 1935, a Nevada newspaper anecdotally described Melungeons as "mulattoes" with "straight hair."[18]

Assimilation

Ariela Gross has shown by analysis of court cases, the shift from "mulatto" to "white" was often dependent upon appearance and, especially, community perception of a person's activities in life: whom one associated with and whether the person fulfilled the common obligations of citizens. Census takers were generally people of a community, so they classified people racially as they were known by the community.[19] Definitions of racial categories were often imprecise and ambiguous, especially for "mulatto" and "free person of color". In the British North American colonies and the United States at times in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, "mulatto" could mean a mixture of African and European, African and Native American, European and Native American, or all three. At the same time, these groups intermarried.

There were questions about which ethnic culture they identified with and often differences between how people identified themselves and how others identified them. Because of slavery, colonial and state laws were biased toward identifying multiracial people of partial African origin as African, although people of African and Native American descent might identify and live as Native Americans culturally. Many Native American tribes were organized around matrilineal kinship systems, in which children were born into the mother's clan and took status from her people.

Because of the loose terminology and social attitudes to mixed-race persons, remnant non-reservation American Indians in the Upper South were generally not recorded separately as Indians. They were often gradually reclassified as mulatto or free people of color, especially as generations intermarried with neighbors of African descent. In the early decades of the 20th century, Virginia and some other states passed laws imposing the one-drop rule, requiring all persons to be classified as either white or black: those of any known African ancestry to be classified as black, regardless of how they self-identified or were known in the community. After Virginia passed its Racial Integrity Act of 1924, officials went so far as to alter existing birth and marriage records to reclassify as "colored" some mixed-race individuals or families who identified as and had been recorded as Indian; this destroyed Indian communities' documented continuity of identity. The historical documentation of continuity of self-identified Native American families was lost. This process of loss of historical and cultural continuity appeared to have happened also with some of the non-reservation remnant Lenape Indians of Delaware.[20]

Since the late twentieth century, Virginia, the Carolinas, and Delaware state governments have each recognized several Native American groups who have documented community continuity as tribes.

Acceptance

The families known as "Melungeons" in the 19th century were generally well integrated into the communities in which they lived, though this is not to say that racism was never a factor in their social interactions. Records show that on the whole they enjoyed the same rights as whites. For example, they held property, voted, and served in the Army; some, such as the Gibsons, owned slaves as early as the 18th century.[21]

Under the first Tennessee constitution of 1796, free people of color (males only) were allowed to vote. Following fears raised by the 1831 Nat Turner slave rebellion, Tennessee and other southern states passed new restrictions on free people of color. By its new constitution of 1834, Tennessee disfranchised them, reducing them to second-class status. In this period, several Melungeon men were tried in Hawkins County in 1846 for "illegal voting", under suspicion of being black or free men of color (and thereby ineligible for voting). They were acquitted, presumably by demonstrating to the court's satisfaction that they had no appreciable black ancestry. Standards were not as strict as under the later laws of the "one drop rule" of the 20th century. As in some other cases, this was chiefly determined by people testifying as to how the men were perceived by the community and whether they had "acted white" by voting, serving in the militia, or undertaking other common citizens' obligations available to white men.[22]

Law was involved not only in recognizing race, but in creating it; the state itself helped make people white. In allowing men of low social status to perform whiteness by voting, serving on juries, and mustering in the militia, the state welcomed every white man into symbolic equality with the Southern planter. Thus, law helped to constitute white men as citizens, and citizens as white men.[22]

After the American Civil War and during the Reconstruction Era, southern whites struggled to re-assert white supremacy over freedmen and traditionally free families such as the Melungeons. Many states passed Jim Crow laws. But issues of race were often brought to court as a result of arguments about money. For example, in 1872, a woman's Melungeon ancestry was evaluated in a trial in Hamilton County, Tennessee. The case was brought by her husband's relatives challenging her inheritance of money after his death. They questioned the legitimacy of a marriage between a white man and a woman known to be Melungeon, and argued the marriage was not legitimate because the woman was of black ancestry. Based on testimony of people in the community, the court decided the woman in the case was not of African ancestry, or not recently enough to matter.[22]

Modern anthropological and sociological studies of Melungeon descendants in Appalachia have demonstrated that they have become culturally indistinguishable from their "non-Melungeon," white neighbors: they share a Baptist religious affiliation and other community features. With changing attitudes and a desire for more work opportunities, numerous descendants of the early Melungeon pioneer families have migrated from Appalachia to other parts of the United States. Notable people of declared Melungeon ancestry include Francis Gary Powers, the U-2 pilot who was shot down over the Soviet Union.[23]

Legends

In spite of being culturally and linguistically identical to their white brothers, these multi-racial families were of a sufficiently different physical appearance to provoke speculation as to their identity and origins. In the first half of the 19th century, the pejorative term "Melungeon" began to be applied to these families by local white (European-American) neighbors. Local "knowledge" or myths soon began to arise about these people who lived in the hills of Eastern Tennessee. According to Pat Elder, the earliest of these was that they were "Indian" (more specifically, "Cherokee").[9] The Melungeon descendant and researcher, Jack Goins, states that the Melungeons claimed to be both Indian and Portuguese. An example was "Spanish Peggy" Gibson, wife of Vardy Collins.

A few ancestors may have been of mixed Iberian (Spanish and/or Portuguese) and African origin. Historian Ira Berlin has noted that some early slaves and free blacks of the charter generation in the colonies were "Atlantic Creoles", mixed-race descendants of Iberian workers and African women in slave ports in Africa. Their male descendants grew up bilingual and accompanied Europeans as workers or slaves.[24] The majority of Melungeon early ancestors, who had migrated from Virginia over time, are northern European and African, given the history of settlement in late 17th–early-18th century eastern Virginia. Later generations in Tennessee intermarried with descendants of Scotch-Irish immigrants who arrived in the mid- to late-18th century and settled in the backcountry before the American Revolution.

Given historical evidence of Native American settlement patterns, Cherokee Nation descent is highly unlikely for the original Melungeon ancestral families, who were formed during the colonial era in the Virginia Tidewater areas, although some of their descendants may have later intermarried with isolated individuals of Cherokee or other Native American ancestry in East Tennessee. Melungeons in Graysville, Tennessee claimed Cherokee ancestors. Anthropologist E. Raymond Evans wrote (1979) regarding these claims:

In Graysville, the Melungeons strongly deny their Black heritage and explain their genetic differences by claiming to have had Cherokee grandmothers. Many of the local whites also claim Cherokee ancestry and appear to accept the Melungeon claim...[25]

The historian, C. S. Everett, hypothesized that John Collins (the Sapony Indian recorded as being expelled from Orange County, Virginia about January 1743), might be the same man as the Melungeon ancestor John Collins, classified as a "mulatto" in 1755 North Carolina records.[26] But Everett has revised that theory after having discovered evidence that these were two different men named John Collins. Only descendants of the latter man, identified as mulatto in the 1755 record in North Carolina, has any proven connection to the Melungeon families of eastern Tennessee.[27]

Other peoples frequently suggested for Melungeon ancestry are the Black Dutch, and the Powhatan Indian group. The Powhatan is an Algonquian-speaking tribe who inhabited eastern Virginia when the English first arrived. Speculation on Melungeon origins continued during the 19th and 20th centuries. Writers recounted folk tales of shipwrecked sailors, lost colonists, hoards of silver, and ancient peoples such as the Carthaginians or Phoenicians. With each writer, new elements were added to the mythology surrounding this group, and more surnames were added to the list of possible Melungeon ancestors. The journalist, Will Allen Dromgoole, wrote several articles on the Melungeons in the 1890s.[28][29]

In the late 20th century, researchers suggested that the Melungeons' ethnic identity may include ancestors who were Turks and Sephardi (Iberian) Jews. The writers David Beers Quinn and Ivor Noel Hume theorize that the Melungeons are descended from Sephardi Jews who fled the Inquisition and came as sailors to North America, and that Francis Drake did not repatriate all the Turks he saved from the sack of Cartagena, but some came to the colonies.[30] Quinn states that "Whether any of them got ashore on the Outer Banks and were deserted there when Drake sailed away we cannot say..."[30] but Janet Crain writes that there is no written proof of this theory.[31] The paper published by Paul Heinegg, Jack Goins, and Roberta Estes in the Journal of Genetic Genealogy does not support the Turkish or Jewish genetics theories.[5]

Etymology

There are many hypotheses about the etymology of the term Melungeon. One plausible explanation favored by linguists and many researchers on the topic, and found in several dictionaries, is that the name derives from the French mélange, or mixture. As there were French Huguenot immigrants in Virginia from 1700, their language could have contributed a term.

Joanne Pezzullo and Karlton Douglas speculate that a more likely derivation of Melungeon, related to the English culture of the colonies, may have been from the now obsolete English word malengin (also spelled mal engin) meaning "guile", "deceit", or "ill intent." It was used by Edmund Spenser as the name of a trickster figure in his epic poem, The Faerie Queene (1590–1596), popular in Elizabethan England.[32] The phrase, "harbored them Melungins," would be equivalent to "harbored someone of ill will", or could mean "harbored evil people", without reference to any ethnicity.

A different explanation traces the word to malungu (or malungo), a Luso-African word from Angola meaning shipmate, derived from the Kimbundu word ma'luno, meaning "companion" or "friend".[33][34] The word Melungo and Mulungo have been found in numerous Portuguese records. It is said to be a derogatory word that Africans used towards people of Portuguese and white ancestry. It could be assumed the word was brought to America through people of African ancestry.[35]

Kennedy (1994) speculates that the word derives from the Turkish melun can (from Arabic mal`un jinn ملعون جنّ), which purportedly means "damned soul." But, the Turkish word can, meaning "soul", is Persian in origin, rather than Arabic. Kennedy apparently confuses it with the Arabic word jinn, better known as genie. He suggests that, at the time, the (condemned soul) was a term used by Turks for Muslims who had been captured and enslaved aboard Spanish galleons.[36]

Some writers try to connect the term Melungeon to an ethnic origin of people designated by that term, but there is no basis for this assumption. It appears the name arose as an exonym, something which neighboring people, of whatever origin, called the multiracial people.

The earliest known written use of the word Melungeon is in an 1813 Scott County, Virginia record at Stony Creek Primitive Baptist Church:

- "Then came forward Sister Kitchen and complained to the church against Susanna Stallard for saying she harbored them Melungins. Sister Sook said she was hurt with her for believing her child and not believing her, and she won't talk to her to get satisfaction, and both is 'pigedish', one against the other. Sister Sook lays it down and the church forgives her."

On October 7, 1840, the polemical Brownlow's Whig of Jonesborough, Tennessee, published an article entitled "Negro Speaking!" The publisher referred to a rival Democratic politician with a party in Sullivan County as "an impudent Malungeon from Washington City a scoundrel who is half Negro and half Indian," [sic] then as a "free negroe". In this and related articles, he does not identify the Democrat by name.[37]

Modern identity

The term Melungeon was traditionally considered an insult, a label applied to Appalachian whites who were by appearance or reputation of mixed-race ancestry, though who were not clearly either "black" or "Indian". In southwest Virginia, the term Ramp was similarly applied to people of mixed race. This term has never shed its pejorative character.[38] In December 1943, Virginia State Registrar of Vital Statistics, Walter Ashby Plecker, sent county officials a letter warning against "colored" families trying to pass as "white" or "Indian" in violation of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 and mentioned by county specific surnames, including: "Lee, Smyth and Wise: Collins, Gibson, (Gipson), Moore, Goins, Ramsey, Delph, Bunch, Freeman, Mise, Barlow, Bolden (Bolin), Mullins, Hawkins (chiefly Tennessee Melungeons)".[39] (Lee County, Virginia borders Hancock County, Tennessee.)

Different researchers have developed their own lists of the surnames of core Melungeon families, as generally, specific lines within families have to be traced. For example, DeMarce (1992) listed Hale as a Melungeon surname.[40] By the mid-to-late 19th century, the term Melungeon appeared to have been used most frequently to refer to the multi-racial families of Hancock County and neighboring areas.[41] Several other uses of the term in the print media, from mid-19th to early 20th century, have been collected at the Melungeon Heritage Association Website.[41] The spelling of the term varied widely, as was common for words and names at the time. Eventually the form "Melungeon" became standard.

Since the late 1960s, "Melungeon" has been increasingly adopted as a self-identified designation of ethnicity. This shift in meaning was probably due to the popularity of Walk Toward the Sunset, a drama written by playwright Kermit Hunter and produced outdoors.[42] The play was first presented in 1969 in Sneedville, the county seat of Hancock County. Making no claim to historical accuracy, Hunter portrayed the Melungeons as indigenous people of uncertain race who were mistakenly perceived as black by neighboring white settlers. As the drama portrayed Melungeons in a positive, romantic light, many individuals began for the first time to self-identify by that term. Hunter intended for his drama "to improve the socio-economic climate" of Hancock County, and to "lift the Melungeon name 'from shame to the hall of fame'."[6] The play helped revive interest in the history of Melungeons. The social changes of the 1960s further contributed to wider acceptance of members of the group. Research in social history and genealogy has documented new facts about people identified as Melungeons.

Popular interest in the Melungeons has grown tremendously since the mid-1990s, although many have left the area of historical concentration. Writer Bill Bryson devoted a chapter to them in his The Lost Continent (1989). N. Brent Kennedy, a non-specialist, wrote a book on his claimed Melungeon roots, The Melungeons: The Resurrection of a Proud People (1994). With the advent of the internet, many people are researching family history and the number of people self-identifying as having Melungeon heritage has increased rapidly, according to Kennedy.[43] Some individuals have begun to self-identify as Melungeons after reading about the group on a website and discovering their surname on the expanding list of "Melungeon-associated" surnames. Others believe they have certain "characteristic" physical traits or conditions, or assume that a multi-racial heritage means they are Melungeon. For example, some Melungeons are allegedly identifiable by shovel-shaped incisors, a dental feature more commonly found among, but not restricted to, Native Americans and Northeast Asians.[44] A second feature attributed by some to Melungeons is an enlarged external occipital protuberance, dubbed an "Anatolian bump", after an unsubstantiated hypothesis, popularized by N. Brent Kennedy, that Melungeons are of Turkish origin.[43][45] Academic historians have not found any evidence for this thesis, nor is it supported by results from the Melungeon DNA Project, which shows an overwhelming northern European and African ancestry of the Melungeon lines.

Internet sites promote the anecdotal claim that Melungeons are more prone to certain diseases, such as sarcoidosis or familial Mediterranean fever. Academic medical centers have noted that neither of the diseases is confined to a single population.[46]

Kennedy's claims of ancestral connections to this group have been disputed. The professional genealogist and historian, Virginia E. DeMarce, reviewed his 1994 book, and found that Kennedy's documentation of his Melungeon ancestry was seriously flawed, as he had a very indistinct definition of Melungeons, although other researchers have studied them extensively. She criticized Kennedy for stretching to include people who might have had other than northern European ancestry, and said that he did not properly take account of existing historical records or recognized genealogical practice in his research. He claimed to have ancestors who were persecuted for racial reasons. However, she found that his named ancestors were all classified as white in records, held various political offices (which showed they could vote and were supported by their community), and were landowners.[47] Kennedy responded to her critique in an article of his own.[48]

The Ridgetop Shawnee Tribe of Indians in Kentucky, which is not federally recognized as an Indian tribe, claims that most families in its area commonly identified as Melungeon are of partial Native American descent and migrated to the region in the late 18th and early to mid-19th centuries. Most families claimed this alternative heritage to explain their dark skin and Indian features and to avoid racial persecution. The Kentucky General Assembly passed resolutions that acknowledged the civic contributions of the Ridgetop Shawnee Tribe of Indians to the state.[49][50]

Similar groups

The following are other multi-racial groups that at one time were classified as tri-racial isolates. Some identify as Native American and have received state recognition, as have six tribes in Virginia.

- Delaware

- Nanticoke-Moors (and in Maryland)[51] Nanticoke groups in Delaware and New Jersey (where they are intermarried with Lenape) have received state recognition. Most had left the area in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

- Florida

- Dead Lake People of Gulf and Calhoun Counties (also known as "Florida Melungeons")

- Dominickers of Holmes County in the Florida Panhandle

- Indiana

- Ben-Ishmael Tribe, pejoratively called "Grasshopper Gypsies"

- Kentucky

- Magoffin County People (Magoffin and Floyd Counties), also known as Brown People of Kentucky or "Kentucky Melungeons"

- Louisiana

- Redbones (and in Texas)

- Maryland

- Piscataway Indian Nation, formerly also known as We-Sorts, one of three Piscataway-related groups recognized as Native American tribes by the state

- New Jersey and New York

- Ramapough Mountain Indians (aka "Jackson Whites") of the Ramapo Mountains, recognized by both New Jersey and New York as Native Americans

- North Carolina

- Coree or "Faircloth" Indians of Carteret County

- Goinstown Indians in Rockingham, Stokes, and Surry Counties

- Haliwa-Saponi, recognized by the state as Native American

- Lumbee, recognized by the state as Native American

- Person County Indians, aka "Cubans and Portuguese"

- Ohio

- South Carolina

- Red Bones (NB: distinct from the Gulf States Redbones)

- Turks

- Brass Ankles

- Virginia

- Goinstown Indians, Henry and Patrick counties

- Monacan Indians (a.k.a. "Issues") of Amherst and Rockingham counties, recognized by state of Virginia as Native American

- West Virginia

- Chestnut Ridge people of Barbour County (also known as Mayles or, pejoratively, "Guineas")

Each of these groupings of multiracial populations has a particular history. There is evidence for connections between some of them, going back to common ancestry in colonial Virginia. For example, the Goins surname group in eastern Tennessee has long been identified as Melungeon. The surname Goins is also found among the Lumbee of southern North Carolina, a multi-racial group that has been recognized by the state as a Native American tribe. In most cases, the multi-racial families have to be traced through specific branches and lines, as all descendants were not considered to be among Melungeons or other groups.

See also

- Black Indians

- Melungeon DNA Project

- List of topics related to the African diaspora

- State recognized tribes in the United States

- Vardy Community School

References

- ↑ William Harlan Gilbert, Jr., "Surviving Indian Groups of the Eastern United States", Report to the Board of Regents of The Smithsonian Institution, 1948

- ↑ Donald B. Ball and John S. Kessler, North from the Mountains: The Carmel Melungeons of Ohio, Paper presented at Melungeon Heritage Association Third Union, 20 May 2000 at University of Virginia's College at Wise, Virginia, Accessed 14 Mar 2008

- 1 2 Ann Toplovich, "Melungeons", Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 25 December 20009, updated 1 January 2010, accessed 18 February 2013

- ↑ Lister, Richard (3 July 2009). "Lost people of Appalachia". BBC News Online. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Roberta J. Estes, Jack H. Goins, Penny Ferguson and Janet Lewis Crain, "Melungeons, A Multi-Ethnic Population", Journal of Genetic Genealogy, April 2012, accessed 25 May 2012

- 1 2 3 4 Shirley Price, "The Melungeons Are Coming Out in the Open", Kingsport Times-News, 28 Jan 1968, accessed 9 Apr 2008

- ↑ Estes et al. (2012), "Melungeons", pp. 8-9

- 1 2 3 Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Delaware and Maryland, 1999–2005

- 1 2 Elder, Pat Spurlock (1999). Melungeons: Examining an Appalachian Legend, Blountville, Tennessee: Continuity Press

- ↑ Travis Loller (AP), "Melungeon DNA Study Reveals Ancestry, Upsets 'A Whole Lot Of People'", Huffington Post, 24 May 2012, accessed 14 February 2013

- ↑ Paul Heinegg, "Church and Cotanch Families", Free African Americans

- 1 2 Jack D. Forbes, "The Use of Racial and Ethnic Terms in America: Management by Manipulation", Wicazo SA Review/The Red Pencil Review, Fall 1995, Vol. XI No. 2, pp. 55,58-59.

- 1 2 3 [Price, Edward T. (1953). "A Geographic Analysis of White-Negro-Indian Racial Mixtures in Eastern United States", Annals of the Association of American Geographers 43 (June 1953): 138–155, accessed 18 February 2013

- ↑ Hancock County, Tennessee Genealogy, Rootsweb

- ↑ "Pittsylvania Co, VA Tax List, 1767". Rootsweb.com. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ↑ "Paul Heinegg, ''Free African Americans'', ''op.cit.'', "Pettiford and Ridley Families"". Freeafricanamericans.com. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ↑ "PERKINS Trial: Instructions to the Jury", 1 July 1858, Original History of Johnson County website, American Local

- ↑ Nevada State Journal, Nov 10, 1935, p.6

- ↑ Ariela Gross, "Of Portuguese Origin": Litigating Identity and Citizenship among the 'Little Races' in Nineteenth-Century America", Law and History Review, Vol. 25, No. 3, Fall 2007, accessed 22 Jun 2008 Archived May 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Dr. Louise Heite, "Delaware's Invisible Indians", Heite Consulting, Inc. Website

- ↑ Heinegg (1999-2010), Free African Americans, Gibson and Gowen Families

- 1 2 3 Ariela Gross, "'Of Portuguese Origin': Litigating Identity and Citizenship among the 'Little Races' in Nineteenth-Century America", Law and History Review, Vol.25, No.3, Fall 2007, accessed 22 Jun 2008 Archived May 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sergei N. Khrushchev, Nikita Khrushchev and the Creation of a Superpower, State College: Penn State Press, 2000, p. 377.

- ↑ Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 1998, pp. 27–32

- ↑ Evans, E. Raymond (1979). "The Graysville Melungeons: A Tri-racial People in Lower East Tennessee", Tennessee Anthropologist IV(1): 1–31.

- ↑ C. S. Everett, "Melungeon History and Myth," Appalachian Journal (1999)

- ↑ "Paul Heinegg, ''Free African Americans,'' ''op.cit.'', Church and Cotanch Families". Freeafricanamericans.com. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ↑ Dromgoole, Will Allen (1890). "Land of the Malungeons", Nashville Daily American, under the name Will Allen, August 31, 1890: 10, reproduced at Melungeon Heritage Association.

- ↑ "Melungeon Heritage Association Website". Melungeon.org. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- 1 2 David Beers Quinn, Set Fair for Roanoke, p. 343]

- ↑ "Myth of Drake Dropping off Passengers", Historical Melungeons

- ↑ Joanne Pezzullo and Karlton Douglas, "Melungeon or Malengin?", Melungeon Heritage Association Website

- ↑ Hashaw, Tim (Jul/Aug 2001) Tim Hashaw, "Malungu: The African Origin of the American Melungeons", Eclectica Magazine

- ↑ Hashaw, Tim (2007) The Birth of Black America: The First African Americans and the Pursuit of Freedom at Jamestown, New York: Basic Books.

- ↑ Quote: "In view of the explanations offered by the Melungo (white man)," The chief replied, "this affair is at an end. It is true that the words used by the negro were very offensive, therefore the Melungeo may procede in peace on his journey, and may he prosper. On your return, if you desire to pass through the lands where I am chieftain, you have my kraals at your command, and I shall be very happy to receive you, because I see that the Melungo is a Oanuna (brave man)." Melungo Diocleciano Fernandes das Neves, A Hunting Expedition to the Transvaal, 1879, p. 28

- ↑ Kennedy (1994)

- ↑ Melanie Sovine, "The Mysterious Melungeons: A Critique of the Mythical Image", 1982, at Historical Association of Melungeons; accessed June 15, 2011

- ↑ Sovine, Melanie L. "The Mysterious Melungeons: a Critique of the Mythical Image." University of KY PHD dissertation, 1982

- ↑ Plecker Letter of December 1943 at Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia.

- ↑ DeMarce, Virginia E. (1992). "Verry Slitly Mixt': Tri-Racial Isolate Families of the Upper South – A Genealogical Study", National Genealogical Society Quarterly 80 (March 1992): pp. 5–35, Historical-Melungeons

- 1 2 "Melungeon Heritage Association Website". Melungeon.org. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ↑ Ivey, Saundra K. Oral, Printed & Popular Culture Traditions Related to the Melungeons of Hancock County, TN, Indiana University dissertation, 1976, accessed 18 February 2013

- 1 2 Kennedy, N. Brent; Robyn Vaughan Kennedy (1997). The Melungeons: The Resurrection of a Proud People: An Untold Story of Ethnic Cleansing in America (2nd ed.). Macon, GA: Mercer University Press. ISBN 0-86554-516-2.

- ↑ "Yuji Mizoguchi, "Shovelling: A Statistical Analysis of Its Morphology", U. of Tokyo, Bulletin No.26, Feb 1985". Um.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ↑ Kennedy, Melungeons, p. 102. Quote: "I came to believe the long-discounted Melungeon claim to be of Portuguese – and even Moorish and Turkish – origin. The 'Mediterranean look' of my own family ..."

- ↑ ""Learning About Familial Mediterranean Fever", National Human Genome Research Institute". Genome.gov. 2011-11-17. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ↑ "Dr. Virginia DeMarce, Review Essay: The Melungeons, ''National Genealogical Quarterly'', Vol. 84, No. 2, June 1996, pp. 134–149". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ↑ "Dr. Brent Kennedy Responds to Virginia DeMarce", Southeastern Kentucky Melungeon Information Exchange

- ↑ "Kentucky General Assembly 2010 Regular Session HJR-16". kentucky.gov, updated 9-2-2010.

- ↑ "Kentucky General Assembly 2009 Regular Session HJR-15". kentucky.gov, updated 5-2-2009.

Note: The resolutions were not an official recognition of tribal status.

- ↑ Delaware's Forgotten Folk – The Story of the Moors and Nanticokes, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

Further reading

- Ball, Bonnie (1992). The Melungeons: Notes on the Origin of a Race' '. Johnson City, Tennessee: Overmountain Press.

- Berry, Brewton (1963). Almost White: A Study of Certain Racial Hybrids in the Eastern United States. New York: Macmillan Press.

- Bible, Jean Patterson (1975). Melungeons Yesterday and Today. Signal Mountain, Tennessee: Mountain Press.

- Brake, Katherine Vande. How They Shine: How They Shine: Melungeon Characters in Fiction of Appalachia. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Brake, Katherine Vande. Through the Back Door: Melungeon Literacies and Twenty-First Century Technologies. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Cavender, Anthony P. "The Melungeons of Upper East Tennessee: Persisting Social Identity," Tennessee Anthropologist 6 (1981): 27-36

- DeMarce, Virginia E. (1993). "Looking at Legends – Lumbee and Melungeon: Applied Genealogy and the Origins of Tri-Racial Isolate Settlements." National Genealogical Society Quarterly 81 (March 1993): 24–45, scanned online, Historical-Melungeons

- Forbes, Jack D. (1993). Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples. University of Illinois Press.

- Goins, Jack H. (2000). Melungeons: And Other Pioneer Families, Blountville, Tennessee: Continuity Press.

- Hashaw, Tim. Children of Perdition: Melungeons and the Struggle of Mixed America. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Heinegg, Paul (2005). FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS OF VIRGINIA, NORTH CAROLINA, SOUTH CAROLINA, MARYLAND AND DELAWARE Including the family histories of more than 80% of those counted as "all other free persons" in the 1790 and 1800 census, Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing, 1999–2005. Available in its entirety online.

- Hirschman, Elizabeth. Melungeons: The Last Lost Tribe in America. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Johnson, Mattie Ruth (1997). My Melungeon Heritage: A Story of Life on Newman's Ridge. Johnson City, Tennessee: Overmountain Press.

- Kennedy , N. Brent (1997) The Melungeons: the resurrection of a proud people. Mercer University Press.

- Kessler, John S. and Donald Ball. North From the Mountains: A Folk History of the Carmel Melungeon Settlement, Highland County, Ohio. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Langdon, Barbara Tracy (1998). The Melungeons: An Annotated Bibliography: References in both Fiction and Nonfiction, Hemphill, Texas: Dogwood Press.

- McGowan, Kathleen (2003). "Where do we really come from?", DISCOVER 24 (5, May 2003)

- Offutt, Chris. (1999) "Melungeons", in Out of the Woods, Simon & Schuster.

- Overbay, DruAnna Williams. Windows on the Past: The Cultural Heritage of Vardy, Hancock County, Tennessee. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Podber, Jacob. The Electronic Front Porch: An Oral History of the Arrival of Modern Media in Rural Appalachia and the Melungeon Community. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Price, Henry R. (1966). "Melungeons: The Vanishing Colony of Newman's Ridge." Conference paper. American Studies Association of Kentucky and Tennessee. March 25–26, 1966.

- Reed, John Shelton (1997). "Mixing in the Mountains", Southern Cultures 3 (Winter 1997): 25–36.(subscription required)

- Scolnick, Joseph M, Jr. and N. Brent Kennedy. From Anatolia to Appalachia: A Turkish American Dialogue. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Vande Brake, Katherine (2001). How They Shine: Melungeon Characters in the Fiction of Appalachia, Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press.

- Williamson, Joel (1980). New People: Miscegenation and Mulattoes in the United States, New York: Free Press.

- Winkler, Wayne (2004). "Walking Toward the Sunset: The Melungeons of Appalachia", Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press.

- Winkler, Wayne (1997). " The Melungeons", All Things Considered. National Public Radio. 21 Sept. 1997.

External links

- Roberta J. Estes, Jack H. Goins, Penny Ferguson, and Janet Lewis Crain "Melungeons, a Multi-Ethnic Population", Journal of Genetic Genealogy, 2011

- Jack Goins Melungeon and Appalachian Research Blog

- Paul Brodwin, ""Bioethics in action" and human population genetics research", Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, Volume 29, Number 2 (2005), 145-178, DOI: 10.1007/s11013-005-7423-2 PDF, addresses issue of 2002 Melungeon DNA study by Kevin Jones, which is unpublished

- Melungeon Heritage Association, Official Website

- "The Graysville Melungeons", Tennessee Anthropologist, Nov 1979, hosted at Rootsweb

- Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware, 1999–2005

- "Melungeons", Digital Library of Appalachia. Contains numerous photographs and documents related to Melungeons, mostly from 1900–1950.

- A Mystery People – The Melungeons From Louis Gates Jr's "Finding your Roots."

- "kindness our heroine shows Melungeon outcast Pearl (Erika Coleman)" from AC-T review of Big-Stone-Gap film. Accessed 6/8/2016