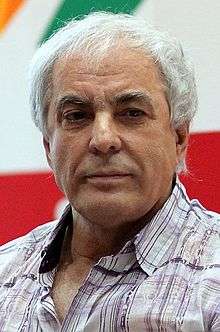

Yuri Nikitin (author)

Yuri Aleksandrovich Nikitin (Russian: Ю́рий Алекса́ндрович Ники́тин), born November 30, 1939 in Kharkiv, USSR, is a Russian science fiction and fantasy writer.

Although he was active in science fiction before perestroika, the recognition came when he wrote a Slavic fantasy novel, The Three from the Forest (Russian: Трое из Леса). One of the protagonists is a character based on the Russian Rurikid Prince Oleg of Novgorod, who is a mainstay of many sequels. Nikitin also wrote a couple of novels about Vladimir I of Kiev. Nikitin created a website called Inn (Russian: Корчма) as a community portal to help young writers.

Nikitin's books have a distinct, free, and often intentionally primitive and repetitive style with many jokes, reflecting his intent to keep the reader on topic and carry his ideas through. His later books develop the ideas of becoming a Transhuman through self-development and survival of the spiritually fittest.

Biography

Yuri Nikitin was born November 30, 1939, in Kharkiv, Ukraine, an only child in a poor family. His father was drafted into the Soviet army soon after and died in the World War II, and his mother never married again. A weaver in a local factory, she raised her son on her own, with the only help of her elderly parents. The four of them lived in a small rustic house in Zhuravlevka, a half-rural suburb of Kharkiv. Nikitin’s grandfather was known as the best carpenter, joiner, and shoemaker in the local area.[1] However, the family could barely make both ends meet: as Nikitin recalled later, in the post-war time they had to eat soup of the potato peelings disposed by their neighbors.[2]

Living in poverty and starvation affected the young Nikitin’s health badly. Born with a heart disease, he also got rickets, rheumatism, and chronic tonsillitis. At the age of 15, Nikitin was told by doctors that he would not live for more than six months, but in the next year he overcame illnesses and improved his health greatly by means of yoga, hard physical exercise, and strict diet.[1]

From his earliest years, Nikitin was bilingual in Ukrainian and Russian, which is rather common for people in Eastern Ukraine. Later, he also learned English and Polish on his own, in order to be able to read the books by foreign SF writers that were not translated in the USSR.[3]

At the age of 16, Nikitin was expelled from school for scuffling and hooliganism and got his first job as a metalworker in a local plant.[4] Two years later, he became a lumberman and rafter in the construction sites of Russian Far North, then a geologist exploring the Ussuri region (Russian Far East) with its swampy coniferous forests, great rivers, and many places where, literally, the foot of man had never stepped before. Bright impressions of those journeys inspired his Saveliy Cycle, a series of short SF stories featuring a hunter from taiga who meets aliens and teaches the art of hunting to them.[5]

In 1964, Nikitin returned to Kharkiv and continued his series of temporary jobs, often low-skilled and involving hard physical work. He lingered in each one for hardly more than a year, mainly because of his wish to try something different. As he commented later in I am 65, his autobiography, “I've never had a job I hated to do. Furthermore, I knew that whatever I did was temporary, that my true destiny was great and my current job nothing but an adventure I’d like to recall someday.” [1]

During 1964-65, Nikitin completed his secondary education as an external student in an evening school and considered seriously his choice of full-time career. He picked sports, music, painting, and writing as the most promising options for the kind of person he was: an ambitious man of 25 with no higher education. By 1967, he achieved the master-of-sports rank in canoeing, first grades in boxing, sambo, track and field athletics, learned to play the violin, sold several cartoons to local magazines.[1]

Nikitin wrote his very first stories in 1965, just for fun. Those were humorous and very short: the shortest one only counted 28 words.[6] All of them were purchased by Russian and Ukrainian magazines. In the next several years, Nikitin created lots of short SF stories (Saveliy Cycle, Makivchuck the Space Ranger Cycle, and many others) with the same distinctive features: new unusual subject, lively characters, fast-changing events, and striking end. In 1973, they were collected to make Nikitin’s first book, The Man Who Changed the World, which was a noticeable success. Many stories were translated into foreign languages and published in the countries of Warsaw Pact. However, the author’s earnings were not enough for living and supporting the family, so he retained his main occupation as a foundry worker till 1976.[1]

Nikitin’s second book, Fire Worshippers, belongs to the genre of industrial novel, which was extremely popular in the Soviet Union. Nikitin wrote it on a bet with his fellow writers who said that writing industrial novels was far more difficult than SF and that he was hardly capable of it. Nikitin bet that he would write such a novel in six months and won.[1] The book received several awards, and a TV series was made on the basis of it. The novel featured real people – Nikitin’s co-workers in the foundry. He even used their real names, and they were pleased by this fact.[7]

In 1976, Nikitin joined both the Communist Party and the USSR Union of Writers. He was the first ever science fiction writer who was not only allowed but invited insistently to do it. The management of both those organizations had rather slighting attitudes towards science fiction in general, but they highly appreciated Fire Worshippers and the fact that Nikitin was a workman without higher education: it was congruent with the aims of Communist propaganda.[1]

Nikitin used his newly-gained opportunities and influence to found the Speculative Fiction Fan Club (SFFC) (Russian: Клуб Любителей Фантастики, КЛФ) in Kharkiv. It was designed as a communication platform for SF writers, scientists and avid readers, a place for literature discussions and critics, and a means to help young SF authors improve their writing skills and get their stories published. In 2003, Nikitin also created SFFC in Moscow.

In 1979, Nikitin wrote his third book, The Golden Rapier: a historical novel about Alexander Zasyadko (1774-1837), a Russian general of Ukrainian origin and inventor of rocket weapons. The contents of the book were found to be inappropriate by Leonid Kravchuk, the head of agitprop department of the Communist Party of Ukraine. He accused Nikitin of Ukrainian nationalism and ordered to destroy all the printed copies of the book.[5]

For his scandalous novel, Nikitin was dismissed from his office in the Union of Writers, banned from publishing in Ukraine, and his name was forbidden to mention in the local media. Also in 1979, he entered the prestigious Higher Literary Courses (HLC) in the Literary Institute, Moscow. The pro-rector of HLC had read The Golden Rapier and so liked it that he accepted Nikitin despite the Communist officials strongly recommending not to do it.[1]

In 1981, Nikitin completed HLC and returned to Kharkiv but could not resume his work as a writer. Whatever he wrote was rejected by publishers for the reason that his name was blacklisted. In 1985, this made him move to Moscow.[8] There Nikitin published his fourth book, The Radiant Far Palace, a collection of short science fiction and fantasy stories.

During perestroika, when some degree of free enterprise was allowed to Soviet citizens, Nikitin in association with other writers founded “Homeland” (Russian: Отечество), one of the first cooperative publishing companies in the country. He worked as a senior editor there for a while, then established his own private publishing company, “Three-Headed Serpent” (Russian: Змей Горыныч), later re-organized into “Ravlik” (Russian: Равлик). It specialized in English and American SF, almost unknown to the Soviet readers before. Books for translation and publishing were selected by Nikitin from his home library that included over 5,000 SF books in English. As he explained later, “I could prepare a hundred volumes of selected sci-fi works as there was no book in my library that I hadn’t read from cover to cover.” [1]

By that time, Nikitin had half a dozen of his own novels written but unpublished. In the USSR, no author was allowed to release more than one book in three years. Another reason that publishers rejected Nikitin's manuscripts was that his protagonists were immortal and happy with it. The Soviet editorial policy was to publish only the works that showed immortality as a terrible and abominable thing; all immortal heroes were expected to repent and commit suicide.[9] In 1992, Nikitin printed the first of those novels, The Three from the Forest, in “Ravlik” – and it was a great success. Each next book of this series became a bestseller.

In the late 1990s, Nikitin abandoned his publishing business and focused entirely on writing books. The rights for them were purchased by major publishing houses: at first "Centrpolygraph" (Russian: Центрполиграф), then "Eksmo" (Russian: Эксмо).

On March 30, 2014, during the Eksmo Book Festival in Moscow, Nikitin officially confessed his writing Richard Longarms, an epic fantasy novel series ongoing since 2001 with over 7,000,000 copies sold in Russia and other countries, under the pen name of Gaius Julius Orlovksy.[10]

Today Nikitin is the author of more than 100 books (including those published under the pen name of Gaius Julius Orlovksy) and one of the most commercially successful Russian writers.[11]

Themes

“The World of SFF” (Russian: Мир фантастики), the largest and most reputable Russian SFF magazine, writes about Nikitin: “It is hard to find another writer whose novels encompass so different themes and target audiences – and inspire such contradictory public response.” [12] Nikitin is a recognized founder of Slavic fantasy, to which The Three from the Forest and The Three Kingdoms belong, but he also worked in the genres of hard SF (The Megaworld), political fiction (The Russians Coming Cycle), social SF about the close-at-hand future (The Strange Novels), comic fantasy (The Teeth Open Wide Cycle), and historical fantasy (The Prince’s Feast, The Hyperborea Cycle).

The Three from the Forest cycle features three protagonists: Targitai, whose prototype is a legendary Scythian king of the same name, Oleg, identified with the historical personality of Slavic Prince Oleg, and Mrak, a strongman and werewolf. They go through the series of adventures in varied settings: the half-mythological lands of Hyperborea and Scythia, then Kievan Rus’, medieval Europe and Middle East. The last novels are set in Russia of the late 1990s (Tower 2), the outer space (Beyondhuman), and alien planets (The Man of Axe). Four books, from The Holy Grail to The Return of Sir Thomas, form a separate sub-cycle telling the story of a heroic quest by Oleg and Sir Thomas, a knight crusader. As of June 2014, the series has 19 books and 6 more are planned.[13]

The Strange Novels fall into the genres of social, psychological, and philosophical SF. The books speculate about the nearest future of Russia and the world. Most attention is given to the problems of personal and social development in the fast-changing hi-tech environment, to the changes that might occur in our present-day morale and culture under the impact of the new technologies. The author is generally optimistic about the future. In his books, those who are strong-willed, hard-working, honest and responsible are likely to become winners.[4]

A peculiarity of The Strange Novels cycle is the absence of mainstay heroes. Except for The Imago and The Immortist, both featuring Bravlin Pechatnik, each novel tells a separate story. The books are only united by the common world and the scope of problems.[4]

The four books of The Russians Coming Cycle are commonly defined as alternate history, but in fact they were political thrillers about the nearest future. The first novel, Rage, was written in 1994 while set in 1996. The protagonist is Platon Krechet, the President of Russia, determined to make his country strong and prosperous. In order to do it, he adopts Islam as the new state religion instead of Russian Orthodoxy. Such a theme was considered unacceptable at that time. No Russian publisher dared to release this novel, despite the unprecedented commercial success of The Three from the Forest several years before, so the first edition of Rage and its two sequels was printed and distributed by Nikitin at his own cost.[14]

Neologisms

Several words invented by Nikitin are now used in Russian language, especially on the web.

- Baim (Russian: байма) – a computer game, especially a MMOG. First used in The Baimer, this term subsequently appears in many other “strange novels” and also in The Reply (Baimer), a collection of short stories by Sergey Sadov.[15] Nikitin explained his reasons to invent this word as the necessity to give the robustly developing industry of computer games its own name, like the term “cinematography” was introduced to replace the old-fashioned “motion picture photography.” [16]

- Einastia (Russian: эйнастия) – a philosophical (or maybe religious) doctrine developed by Oleg, the protagonist in The Three from the Forest cycle. Einastia is mentioned in several books of the series but its essence is never described and hence remains an issue of debate among Nikitin’s fans. The author prefers not to answer direct questions about the meaning of this word.

- Usians (Russian: юсовцы, derived from the USA) – a kind of people, particularly (but not necessarily) in the USA, who have a range of distinctive negative features, including:

- Adherence to “universal values”, often understood primitively;

- Devil-may-care attitudes towards other people;

- Following a set of principles like “self comes first,” “don’t be a hero” etc.[17]

Personal life

Nikitin has two children of his first marriage, which ended with his wife's death. In 1990, he met Lilia Shishikina, an experienced bookseller, and she became his business companion and common-law wife. For several years she was in charge of "Ravlik".

On May 22, 2010 Nikitin married Lilia during a small ceremony at their home in Red Eagles (Russian: Красные Орлы), a cottage settlement near Moscow. Only their closest friends were invited.[18]

Nikitin is fascinated with new technologies: he monitors the hi-tech news thrice a day,[19] has six computers at home and many electronic devices, which he upgrades and changes for newer models regularly.[20] He also loves to play real-time strategies and spends 2–3 hours a day on average in MMOGs.[21]

For over 30 years, Nikitin gave not a single interview, visited no conference or SF convention, and held no meeting with readers. This situation only changed after the release of Transhuman.[20]

As of June 2014, Yuri Nikitin is a frequent visitor to the online forum Transhuman (Russian: Трансчеловек) where he has the nickname of Frog, being one of the first registered members and an honorary administrator. This website is the main platform of Nikitin’s online communication with fans and readers as he has a skeptical attitude towards blogging.[22] Also, there are online clubs of Nikitin’s fans in Facebook and VK.

Today Nikitin and his wife live in Falcon Hill (Russian: Соколиная гора), a cottage settlement near Moscow. They have a pet boxer Linda. As noted by fans, Nikitin has lent his passion for strong sweet black coffee to nearly all his heroes.[20] Nikitin prefers a healthy way of life: for many years, he drinks no alcohol and practices cycling and weightlifting as a hobby.[20]

Bibliography

The Three from the Forest Cycle

- In the Very Beginning (2008) (Russian: Начало всех начал)

- The Three from the Forest (1992) (Russian: Трое из леса)

- The Three in the Sands (1993) (Russian: Трое в песках)

- The Three and the Gods (1994) (Russian: Трое и боги)

- The Three in the Valley (1997) (Russian: Трое в долине)

- Mrak (1996) (Russian: Мрак)

- A Respite in Barbus (2004) (Russian: Передышка в Барбусе)

- The Secret Seven (1998) (Russian: Семеро тайных)

- The Outcast (2000) (Russian: Изгой)

- The Slayer of Magic (2010) (Russian: Истребивший магию)

- Faramund (1999) (Russian: Фарамунд)

- The Hyperborean (1995) (Russian: Гиперборей)

- The Holy Grail/The Grail of Sir Thomas (1994) (Russian: Святой грааль)

- The Stonehenge/The Secret of Stonehenge (1994) (Russian: Стоунхендж)

- The Revelation (1996) (Russian: Откровение)

- The Return of Sir Thomas (2006) (Russian: Возвращение Томаса)

- Tower 2 (1999) (Russian: Башня-2)

- The Man of Axe (2003) (Russian: Человек с топором)

- Beyondhuman (2003) (Russian: Зачеловек)

The Richard Longarms Cycle (as Gaius Julius Orlovsky)

- Richard Longarms 1: Stranger (2001) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки)

- Richard Longarms 2: Warrior of God (2001) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - воин Господа)

- Richard Longarms 3: Paladin of God (2002) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - паладин Господа)

- Richard Longarms 4: Seignior (2003) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - сеньор)

- Richard Longarms 5: Richard de Amalphie (2004) (Russian: Ричард де Амальфи)

- Richard Longarms 6: Lord of Three Castles (2004) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - властелин трех замков)

- Richard Longarms 7: Viscount (2005) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - виконт)

- Richard Longarms 8: Baron (2005) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - барон)

- Richard Longarms 9: Jarl (2005) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - ярл)

- Richard Longarms 10: Earl (2005) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - граф)

- Richard Longarms 11: Burggraf (2006) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - бургграф)

- Richard Longarms 12: Landlord (2006) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - лендлорд)

- Richard Longarms 13: Pfaltzgraf (2007) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - пфальцграф)

- Richard Longarms 14: Overlord (2007) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - оверлорд)

- Richard Longarms 15: Constable (2007) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - коннетабль)

- Richard Longarms 16: Marquis (2008) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - маркиз)

- Richard Longarms 17: Grossgraf (2008) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - гроссграф)

- Richard Longarms 18: Lord Protector (2008) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - лорд-протектор)

- Richard Longarms 19: Majordom (2008) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - майордом)

- Richard Longarms 20: Markgraf (2009) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - маркграф)

- Richard Longarms 21: Gaugraf (2009) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - гауграф)

- Richard Longarms 22: Freigraf (2009) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - фрайграф)

- Richard Longarms 23: Wieldgraf (2009) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - вильдграф)

- Richard Longarms 24: Raugraf (2010) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - рауграф)

- Richard Longarms 25: Konung (2010) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - конунг)

- Richard Longarms 26: Duke (2010) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - герцог)

- Richard Longarms 27: Archduke (2010) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - эрцгерцог)

- Richard Longarms 28: Furst (2011) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - фюрст)

- Richard Longarms 29: Kurfurst (2011) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - курфюрст)

- Richard Longarms 30: Grossfurst (2011) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - гроссфюрст)

- Richard Longarms 31: Landesfurst (2011) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - ландесфюрст)

- Richard Longarms 32: Grand (2011) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - гранд)

- Richard Longarms 33: Grand Duke (2012) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - князь)

- Richard Longarms 34: Archfurst (2012) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - эрцфюрст)

- Richard Longarms 35: Reichsfurst (2012) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - рейхсфюрст)

- Richard Longarms 36: Prince (2012) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - принц)

- Richard Longarms 37: Prince Consort (2012) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - принц-консорт)

- Richard Longarms 38: Vice-Prince (2012) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - вице-принц)

- Richard Longarms 39: Archprince (2012) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - эрцпринц)

- Richard Longarms 40: Kurprince (2013) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - курпринц)

- Richard Longarms 41: Erbprince (2013) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - эрбпринц)

- Richard Longarms 42: Crown Prince (2013) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - принц короны)

- Richard Longarms 43: Grand Prince (2013) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - грандпринц)

- Richard Longarms 44: Prince Regent (2013) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - принц-регент)

- Richard Longarms 45: King (2013) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - король)

- Richard Longarms 46: King Consort (2013) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - король-консорт)

- Richard Longarms 47: Monarch (2014) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - монарх)

- Richard Longarms 48: Stadtholder (2014) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - штатгалтер)

- Richard Longarms 49: Prince of the Emperor's Mantle (2014) (Russian: Ричард Длинные Руки - принц императорской мантии)

The Prince's Feast Cycle

- The Prince's Feast (1997) (Russian: Княжеский пир)

- The Final Fight (1999) (Russian: Главный бой)

The Hyperborea Cycle

- Prince Rus (1996) (Russian: Князь Рус)

- Ingvar and Olha (1995) (Russian: Ингвар и Ольха)

- Prince Vladimir (1995) (Russian: Князь Владимир)

The Teeth Open Wide Cycle

- Teeth Wide Open (1998) (Russian: Зубы настежь)

- Ears Up In Tubes (2003) (Russian: Уши в трубочку)

- The Three-Handed Sword (2003) (Russian: Трехручный меч)

The Three Kingdoms Cycle

- Artania (2002) (Russian: Артания)

- Pridon (2002) (Russian: Придон)

- Kuyavia (2003) (Russian: Куявия)

- Jutland, Brother of Pridon (2011) (Russian: Ютланд, брат Придона)

The Megaworld Cycle

- Megaworld (1991) (Russian: Мегамир)

- The Lords of Megaworld (2000) (Russian: Владыки мегамира)

The Ballads of Great Knights

- Lohengrin, the Swan Knight (2012) (Russian: Лоэнгрин, рыцарь Лебедя)

- Tannhauser (2012) (Russian: Тангейзер)

The Strange Novels

- I Live in This Body (1999) (Russian: Я живу в этом теле)

- Scythians (2000) (Russian: Скифы)

- The Baimer (2001) (Russian: Баймер)

- The Imago (2002) (Russian: Имаго)

- The Immortist (2003) (Russian: Имортист)

- The Sorcerer of Agudy Starship (2003) (Russian: Чародей звездолета "Агуди")

- The Great Mage (2004) (Russian: Великий маг)

- Our Land is Great and Plentiful (2004) (Russian: Земля наша велика и обильна...)[23]

- The Last Stronghold (2006) (Russian: Последняя крепость)

- Passing Through Walls (2006) (Russian: Проходящий сквозь стены)

- Transhuman (2006) (Russian: Трансчеловек)

- Worldmakers (2007) (Russian: Творцы миров)

- I Am a Singular (2007) (Russian: Я - сингуляр)

- Singomakers (2008) (Russian: Сингомэйкеры)

- 2024 (2009) (Russian: 2024-й)

- Guy Gisborn, a Knight Valiant (2011) (Russian: О благородном рыцаре Гае Гисборне)

- Dawnpeople (2011) (Russian: Рассветники)

- The Nasts (2013) (Russian: Насты)

- Alouette, little Alouette... (2014)

The Russians Are Coming Cycle

See "The Russians are coming" for the origin of the cycle name (Русские идут)

- Rage (1997) (Russian: Ярость)

- The Empire of Evil (1998) (Russian: Империя зла)

- On the Dark Side (1999) (Russian: На темной стороне )

- The Horn of Jericho (2000) (Russian: Труба Иерихона)

Other books

- Fire Worshippers (1976) (Russian: Огнепоклонники)

- The Golden Rapier (1979) (Russian: Золотая шпага)

- How to Become a Writer (2004) (Russian: Как стать писателем)

- I am 65 (2004) (Russian: Мне 65)

Collections

- The Man Who Changed the World (1973) (Russian: Человек, изменивший мир)

- The Radiant Far Palace (1985) (Russian: Далекий светлый терем)

- Singularity (2009) (Russian: Сингулярность)

- Singularity 2 (2012) (Russian: Сингулярность-2)

Foreign releases

In the post-Soviet period, there were no official foreign releases of Nikitin’s books. However, some of Nikitin’s short stories can be found in English on the web, e. g. Sisyphus translated by David Schwab.[24]

In 2013, a group of Nikitin’s fans, with the author’s consent, translated into English The Holy Grail (title changed to The Grail of Sir Thomas) and offered it as a free e-book on a range of online SFF forums.[25][26][27]

As of June 2014, the English versions of three novels by Yury Nikitin (In the Very Beginning, The Grail of Sir Thomas, The Secret of Stonehenge) are available as e-books in major online retailers.[28]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yury Nikitin. |

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Nikitin, Yuri. "Мне 65." [I am 65.] (In Russian). 2004. Moscow: Eksmo. ISBN 5-699-07045-1

- ↑ Nikitin, Yury. Re #69: Правильное питание. (Re #69: Proper Nutrition.) (In Russian.) Transhuman.com. 12 Sept. 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Glebova, Irina. "Мой друг Юрий Никитин." [My friend Yuri Nikitin.] (In Russian.) 22 Oct. 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 Nevsky, Boris. Бросающий вызов: Юрий Никитин [Yuri Nikitin: The Challenger.] (In Russian.) Мир фантастики [The World of CFF], vol. 91, March 2011.

- 1 2 Nikitin, Yuri (1996). Preface. In "Человек, изменивший мир" [The Man Who Changed the World.] (In Russian). Moscow: Eksmo. 2007. ISBN 978-5-699-22164-6

- ↑ Nikitin, Yury. Re #2113: Вопросы Никитину. (Re #2113: Questions for Nikitin.) (In Russian.) Transhuman.com. 30 Oct. 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Nikitin, Yury. Re #119: Вопросы Никитину. (Re #119: Questions for Nikitin.) (In Russian.) Transhuman.com. 2 Jan. 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Nikitin, Yury. Re #3222: Вопросы Никитину. (Re #3222: Questions for Nikitin.) (In Russian.) Transhuman.com. 15 Aug. 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Nikitin, Yuri (2006). Preface. In "Трансчеловек" [Transhuman]. (In Russian). Moscow: Eksmo. 2006. ISBN 5-699-15001-3

- ↑ Wolf, Ingrid. Orlovsky Shows His Face on YouTube. (Video.) (Subtitled in English.) Youtube.com. 1 Apr. 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Eksmo.ru. Yuri Nikitin Author’s Page. (In Russian.) Eksmo.ru. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ Zlotnitsky, Dmitry & Vladimir Leshchenko. Беседа с Юрием Никитиным. [Interview with Yuri Nikitin] (In Russian.) Мир фантастики [The World of SFF], vol. 37, September 2006.

- ↑ Fantlab.ru. Yuri Nikitin Author’s Page (In Russian.) Fantlab.ru. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ Nikitin, Yuri (2004). "Как стать писателем." [How to Become a Writer] (In Russian.) Moscow: Eksmo. ISBN 5-699-04992-4

- ↑ Sadov, Sergey. Ответ (Баймер). [The Reply (Baimer)] (In Russian.)

- ↑ Nikitin, Yuri (2001). Баймер. [The Baimer] (In Russian.) Moscow: Eksmo. ISBN 5-699-19535-1

- ↑ Murz. Про юсовцев. [About Usians] (In Russian.) Korchma. 3 Nov. 2002. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ RusEventProject. Трогательная свадьба для самых близких друзей. [A touching wedding for the closest friends.] (In Russian.) RusEventProject. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ Nikitin, Yury. Re #27: Очки доп. реальности. (Re #27: Augmented Reality Glasses.)(In Russian.) Transhuman.com. 15 March 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Transhuman.com. Часто задаваемые вопросы Юрию Никитину (Frequently Asked Questions to Yury Nikitin). (In Russian.) Transhuman.com. Updated 19 Oct. 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Nikitin, Yury. Re #59: Об армии. (Re #59: About the Army.) (In Russian.) Transhuman.com. 12 March 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Nikitin, Yury. Re #3730: Вопросы Никитину. (Re #3730: Questions for Nikitin.) (In Russian.) Transhuman.com. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ A quote from the Russian Primary Chronicle,

- ↑ Nikitin, Yury. Sisyphus. Trans. David Schwab. All Things If. 15 Feb. 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Yafet. A FREE action-packed fantasy book by Russian bestselling writer. SFFWorld.com. 24 Jan. 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Yafet. A FREE action-packed fantasy book by Russian bestselling writer. Fantasy-Faction.com. 25 Jan. 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Yafet. A FREE action-packed fantasy book by Russian bestselling writer. BestFantasyBooks.com. 25 Jan. 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Amazon.com. Yury Nikitin's Author Page. Amazon.com. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

External links

- Корчма. [The Inn.] (In Russian.)

- Форум Трансчеловек. [Transhuman.com]. (In Russian.)

- Yury Nikitin's Author Page on Amazon

- Yury Nikitin's Author Page on Smashwords