Want of Matter

“Want of Matter” (in Hebrew: דלות החומר; Dalut HaHahomer) is an Israeli style of art that existed in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Characteristics of this style include the use of “meager” creative materials, artistic sloppiness, and criticism of the social reality and the myth of Israel society. Among the artists identified with “Want of Matter” are Raffi Lavie, Yair Garbuz, Michal Na'aman, Tamar Getter and Nahum Tevet.

History

The “Want of Matter” style grew out of a historical-retrospective view of Israeli art. The name originated in an exhibition called “The Want of Matter: A Quality in Israeli Art” curated by Sara Breitberg-Semel, which took place in March 1986 at the Tel Aviv Museum. Breitberg-Semel, then curator of Israeli art at the museum, mounted this exhibition as a summation and continuation of the exhibitions “Artist,Society,Artist” and “Different Spirit” (1981). It was an attempt to distinguish between local art and the style of international art of this period by means of a sociological and esthetic survey of Israeli artists and their attitude toward European artistic traditions. Breitberg-Semel saw the roots of the style in Pop Art, Arte Povera and Conceptual art. Another highly significant element in Breitberg-Semel’s view was the concept “anesthetic,” the roots of which could be found in the Jewish Talmudic tradition, which puts the text in the center of culture.

Breitberg-Semel’s attempt to trace the development of “Want of Matter” gave rise to a clear historical line, beginning with the painting of the “New Horizons” group. The members of this group developed an abstract style that came to be known as “lyrical abstract” within the framework of which the painters created an abstraction of form influenced by Expressionism. The artists who followed in the footsteps of these artists, Aviva Uri and Arie Aroch, used the artists of the “Want of Matter” group as their esthetic model with regard to their relationship to the materials they used in their paintings, to their ascetic materialism, and to their combined use of the abstract and veiled iconography.

The first generation of artists in the “Want of Matter” group in the 1960s were partners in a number of avant-garde artistic experiments, the most important of which were the activities of a group called “10+” This group, which never had a unified political or esthetic direction, united around the influences of international art and the use of new artistic materials such as photographs to create two dimensional art, artistic “activity,” and even the use of the pioneering video art films in Israel.

Visually, "The Want of Matter" style distilled its characteristics from these diverse influences, preferring painting to three-dimensional sculpture. Overall, this style can be summed up as focusing on the use of low-cost materials identified with the establishment of Israel, such as plywood, cardboard, collages, photographs arranged as collages, industrial paints, and writing and scribbling within the work. The use of these materials reflected the “Ars Poetica” approach and gave an intentionally humble appearance to the surface of the paintings, a look which was meant to add a dimension of criticism by the artists toward Israeli society.

“But the word is very near you”

The caption on the exhibit “Want of Matter” included a quotation from the Book of Deuteronomy (30:14) -- “But the word is very near you.” This quotation captured the point of view of this group of artists, according to Breitberg-Semel, a secular, modernist point of view mixed with Jewish symbolism. The works were pointedly free of religious symbolism, as Breitberg –Semel notes, defining the works of Raffi Lavie: “There is no Western Wall, no Old City Wall, no Augusta Victoria,” while on the other hand, the works were created “against the background of a religion whose esthetic and non-materialist point of view were its symbols.” The development of this idea can be seen the article “Agrippas versus Nimrod” (1988), in which Breitberg-Semel expressed the desire to inculcate into their art a secular, pluralistic point of view influenced by Jewish tradition. The identification of Judaism with abstract art had already happened in the past, when it was based on the iconoclastic Orthodox tradition, in the spirit of the prohibition against the making of statues or masks that appears in The Ten Commandments. In 1976 this idea appeared in the Hebrew translation of an article by the American art critic Robert Pincus Witten, published in the first issue of the art journal Musag (in Hebrew: "Concept").[1] The typical expression of this point of view on the Israeli artist can be found in an article on the work of Arie Aroch, who is considered the model for Raffi Lavie and his generation. The concept of “anestheticism” fueled the writings of the young artists, as an image within the works themselves, writing which relates to the relationship between the Jewish Talmudic tradition and a preoccupation with borders and national symbols as an expression of critical Zionist Judaism. In Breitberg-Semel’s writing, these artists are portrayed as the “disinherited sabra,” cut off from Jewish tradition to the same degree that they were cut off from the European Christian tradition.

Raffi Lavie – “Child of Tel Aviv”

In the article by Breitberg-Semel that accompanied the “Want of Matter” exhibition, the artist Raffi Lavie was presented as the typical representative of the style. Lavie’s works put forth the idea of “The City of Tel Aviv” as a combination of European-Zionist modernism and neglect and abandonment. As the years passed, the image of Lavie himself, dressed sloppily in shorts, with rubber flip-flops on his feet, arrogant, “native,” and “prickly,” became the typical expression of this aesthetic school.[2] Lavie’s works, which included childish scribbles, collages of magazine illustrations, advertisements of Tel Aviv cultural events, stickers with words “head” or “geraniums” written on them, and above all the plywood sheet, sawed to a consistent size of 120 cm., and painted in whitewash,[3] became the most recognizable symbols of “Want of Matter.”

In addition to developing a comprehensive visual style, Lavie encouraged discussion of his works on a formalist level. In interviews, Lavie refused to relate to any interpretations of his work other than “the language of art” in its modernist aesthetic incarnation. In spite of clearly iconographic images in his works, Lavie insisted that these images were of no historical significance. Furthermore, the use of collage and techniques that lacked an artistic “halo” were intended, according to both Lavie and Breitberg-Semel, to erode and undermine the significance of visual images.[4] Lavie’s students, however, continued to cultivate a preoccupation with form, as well as a continuing relationship with the modernist tradition, both of which caused problems for Lavie’s didactic separation of “form” and “content.”[5]

Yair Garbuz formed a relationship with Lavie when he was just a young boy. For a number of years Lavie was Garbuz’s private teacher.[6] Later Garbuz went from being a student to being a senior instructor at the “HaMidrasha” (School of Art). His work from these years created a link between the symbols that connected the ethos of the Zionist undertaking, as reflected in popular culture, with social and political criticism.

His two-dimensional works from the 1970s and 1980s include a mix of newspaper photos, documentary photographs, texts and other objects, combined in compositions that have no clear hierarchy. Some of his works, such as "The Evenings (Arabs) Pass By Quietly" (1979) and "The Arab Village in Israel Very Much Resembles the Life of our Forefathers in Ancient Times" (1981), criticized stereotypes rampant in Israeli society. For the cover he designed for No. 11 of the journal Siman Kriah [Exclamation Point] (May 1980), Garbuz inserted a photograph from the newspaper Davar of a self-portrait of Vincent Van Gogh captioned “Van Gogh in Tel Aviv.” Under the reproduction, Garbuz added a sort of poem, complete with nikud [vocalization] and illustrations, discussing the significance of labor. This work was one of a number of his works in which he presented his artistic activity as an artist in Israel - which he perceived as a distant and outlying place — as a kind of anarchism. Along with these two-dimensional works, Garbuz produced art videos, installations, and other forms of artistic activities in this spirit.

Henry Schlesnyak, an American-born artist, juxtaposed collage with American Pop Art, and American symbolism—the most significant of which is his portrait of Abraham Lincoln – with scenes from Israeli art as reflected in various newspaper articles. Through this juxtaposition, Schlesnyak pointed out the moral aspect of artistic activity and his view of the place of Israeli art and the Israeli artist within it. Another layer of his work was composed of the “Tel Aviv” aesthetic, which played the role of critic in his works. For example reproductions of famous works of art were painted over in industrial shellac to give them the feeling of paintings by the European “Old Masters.” The “Hebrew translation” of this feeling included the devaluing of the paintings by “flashes of stains on the surface of the paintings, dirt, ‘want of matter’, thereby bringing it down to the level of what is appropriate to the experience of being here. “[7] In a 1980 collage, Schlesnyak glued onto plywood a newspaper picture of the writer Irving Stone, author of popular novels about artists, positioned at the front of the Tel Aviv Museum. Next to him stands Marc Scheps, Director of the museum, with his head enclosed in a circle. Above this Schlesnyak glued an article by Adam Baruch describing an exhibition of the works of Ya’acov Dorchin, a friend of Schlesnyak, with a caption composed of letterset printing.

The works of Michal Na'aman from the 1970s used photography to create collages. In these works Naaman put together various expressions emphasizing the limitations of the language of description and of vision, as well as the possibilities of imagination and the difference in visual expression. The practice of combining conflicting axioms indicated the failure or distortion of the language of description.[8] Against the background of the visual dimension that reflected the aesthetic principles of “Want of Matter,” there appeared various representations and texts written in letterset printing[9] or in handwriting that reflected the semiotic bankruptcy of the representation of images. Examples of this can be found in works such as “The Fish is the End of the Bird” (1977) and “The Gospel According to the Bird” (1977) in which Na'aman joined reproduced images of a fish and a bird into a kind of hybrid monster. In “Vanya (Vajezath)" (1975) a conflict is created between the textual contents of the work with the visual contents, along with an emphasis on sexual motifs.

In spite of her feminist connections, Yehudit Levin’s works are more personal and less intellectual than the works of most of Raffi Lavie’s students. At the end of the 1970s and early 1980s, Levin created abstract compositions constructed from sawed and painted plywood, sometimes combined with photographs, then leaned against a wall. The names of these works, such as “Bicycle” (1977) and “Princess in a Palace” (1978) hint at a domestic connection. Even though these works appear in space as three-dimensional, their main interest lies in their complex relationship with the spaces seen within them. The “drawing” breaks out of the framework of the platform and flows over into space.

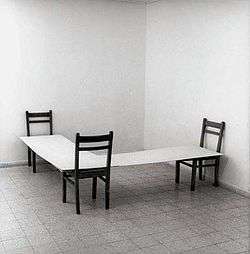

A similar approach, without the psychological baggage, can be seen in the works of the sculptor Nahum Tevet. In his minimalist works Tevet shows an ambivalent relationship with three-dimensional space. In a late interview Tevet defined the motivation behind these works as a reaction to his studying art with Lavie. “It might be that to a certain extent this is a reaction to the place where I studied painting, in Raffi Lavie’s studio. He suggested painting in which the main interest was built around personal tensions and relationships, and I asked about the relationship between the painting as an object and the environment – the world.”[10]

His works from that period dealt with the division and organization of work surfaces. In an installation from 1973-1974, Tevet placed white-painted plywood boards on top of chairs. The work showed the influence of the aesthetic principles of minimalist art and emphasized the temporariness of the expression of an artistic experience. In another work, “Beds” (1974), Tevet displayed rectangular, white-painted plywood boards, with legs attached to them that turned the two-dimensional “painting” into a work of sculpture. The interpretation of this work that grew up over the years required that, in addition to the formalistic aspect of the work, the biographical background of Tevet, as a former kibbutz member, needed to be taken into account. Relating to plywood as a “painting” and to its placement as a work of art[11] reflected the ambivalent relationship of Tevet to the surface of the painting.

Hamidrasha School of Art

In 1966 Lavie joined the staff of Hamidrasha Art Teachers College in Ramat Hasharon, known as “Hamidrasha School of Art.” Around this educational institution a group of Lavie’s students, such as Michal Na’aman, Yehudit Levin, etc., grew up and began teaching there. As a group these artists formed a clear hegemony over art in the period following “New Horizons.”

The teaching method at Hamidrasha centered around the discussion of art and modern aesthetics, demoting the more traditional method of teaching art, which focused on drawing lessons opposite a model, to second place. The rational that gave rise to this pedagogical method sprung from the assumption that in a world in which art was expressed in endless new ways of execution, there was no way to learn all the new artistic techniques. Therefore the school tried to educate its art students first and foremost as “artists” and assumed that they would develop their technical skills independently, in accordance with their individual needs.

A great many academic areas at Hamidrasha were subordinated to this pedagogic approach. “I reject all academic degrees and any attempt at the academization of the study of art in any form,” Lavie stated in a dialogue between him and Pinchas Cohen Gan. “I don’t think it’s possible to give out grades, and I don’t believe it’s possible to judge art.”[12] As an answer to the inability to make judgments about art, which Lavie pointed out, the institution developed “public” criticism. Within the framework of this criticism, which was often dubbed “The Ceremony,” teachers were invited to a public discussion of their students’ work.

The “Criticism” demonstrated the centrality of the personality and the status of the teachers on the framework of the studies. Tsibi Geva, who was a student in the Hamidrasha and later became a teacher there, described Lavie as a central figure in art, through which the world of art was perceived…”We received everything through Raffi Lavie. The man controlled the flow; and he was, you could say, the authority that legislated and the authority that carried things out. He was the window onto the world; our education was acquired through the prism of his eyes.”[13] Apart from the its teaching, Hamidrasha provided favored graduates with entrance to the “Hamidrasha School.” Within this framework, Lavie encouraged exhibitions of the school’s graduates. In May 1974 Lavie distributed a “pamphlet” in which he presented works by students who were close to him, such as Naaman, Tevet, David Ginton, etc., and aroused a storm of negative criticism. The Ross Gallery in north Tel Aviv also consistently displayed the artists of the new School.[14] Later the artists of the School began displaying their works in the Julie M Gallery and the Givon Gallery in the center of Tel Aviv as well.

The Struggle to Be the Center: Tel Aviv and Jerusalem

The exhibition “Want of Matter” presented the group of “Tel Aviv Artists” as the center of contemporary Israel art. In addition to representing the Socialistic-Pioneering spirit, these artists represented the secular character of Tel Aviv, under the banner of “the aesthetic, non-materialistic aspect of the Jewish tradition.”[15] The group strengthened its sense of its own identity by forming a network of personal and professional connections among themselves. In the article, “About Raffi: Color patch, Crown. Catchup, Love” (1999), Yair Garbuz, Lavie’s student, presented his teacher in terms of his originality. “It’s not that we suddenly became the center of art… we’ve remained the provinces [...] In a certainly respect, Raffi painted and taught like a pioneer. In order for something to flourish here, it had to be carefully disguised. You couldn’t just say that maybe modernism was developing.”[16] The period before the existence of “Want of Matter” was perceived by this group of artists as a mixture of immature explorations of abstract modernism with overtones of the romantic aesthetic, overtones which Lavie and his followers viewed as a danger capable of reducing art to something lacking in the characteristics and criteria of aesthetic judgment.[17]

The tradition that Want of Matter created for itself attempted to follow what was happening in American and European conceptual Art. However, in contrast to them, this conceptualism was seen primarily within the framework of painting. Ariella Azoulay stated, in an analysis of the Israeli artistic scene, that this choice of painting as the dominant medium in Israeli art, was not a natural process, but rather was carefully directed by certain elements such as Sarah Breitberg-Semel, the museum and the art establishment, as well as the artists themselves.[18] In fact, the choice of works by Breitberg-Semel for the exhibition honored works from the exhibit that were created by the same group of artists she had chosen to exhibit, but they were done using techniques other than painting.[19] Examples of this are the video art films of Lavie and Garbuz, the mixed media works and installations of Michal Naaman, etc. Outside the museum establishment, avant-garde art such as mixed media works, installations and other conceptual projects that couldn’t be displayed at museums continued to be produced. Criticism of this kind was also heard during the exhibition.[20] Only in the 1980s, Azoulay contends, with the weakening of the status of the central museums, did these trends, that were suppressed until then, rise to the top of Israeli art.

The attempt to present “Want of Matter” as the dominant hegemony in Israeli art, as the “center” of Israeli art, pushed many Israeli artists to the periphery of this center. Gideon Efrat, an art critic and curator set up a comparison between “Tel Aviv-ness” and the “School of New Jerusalem,” a term based on the metaphysical Christian interpretation of the city of Jerusalem. The main difference between the definition of this group and that of the “Tel Aviv School,” according to Breitberg-Semel, lay in the difference between their definitions of the status of art in relation to public space. While the “Tel Aviv” group strove to focus their art within the traditional definitions, the “Jerusalem artists” sought to draw an “eruv” – a ritual shared enclosed area – around art and life. Artists such as Gabi Klasmer and Sharon Keren (“Gabi and Sharon”) appeared in a series of performances of a political nature in Jerusalem public places; Avital Geva and Moshe Gershuni met with Yitzhak Ben-Aharon, Secretary General of the Histadrut, as an “activity”[21] of “art.”[22]

In contrast, the “Tel Avivans,” led by Lavie, developed a purist concept of art. In his view, art should focus on the physical boundaries of the plastic arts – on color, line, stain, and their relationship to the format of the work. In a 1973 interview, Lavie spoke about politics in art: “If an artist wants to say political things through his work, it’s his privilege. But he should know exactly what the work is called: a “placard.”[23]

In the exhibition “Eyes of the Nation,” held at the Tel Aviv Museum in 1998, Ellen Ginton viewed the art of the period as a reaction to the political and social problems in Israeli society. This perspective undermined the traditional dichotomy that Efrat and Breitberg-Semel presented. Ginton held that this art was a response to the political and social crisis after the Yom Kippur War which continued into the 1980s. Eventually, the artists returned to more traditional artistic activity.[24]

The Sabra and the Exile

Another kind of criticism, political in nature, was directed against “Want of Matter” and the wide acceptance of Breitberg-Semel’s thesis. In 1991 Breitberg-Semel’s article “Want of Matter” was re-published, and she wrote a new introduction for it. In this new introduction she attempted to clarify the critical dimension of her thesis, declaring that “the generation that grew up after 1967 encountered a new ethos – the rule by occupation, with all its moral and material implications, and with all its enormous social changes, of which the bourgeois existence as the leading way of life, is only one aspect. This generation of artists, which would have difficulty freeing itself of the cultural images the exhibition bequeathed to them with regard to the dispute over local culture, would also have difficulty waving the flag of “want of matter” as the achievement that belongs to it and characterizes it. But perhaps, one day, things would change.[25] The division in “want of matter” between “ethos” and “aethestics” is presented in the introduction as a fleeting moment, since the use that was made of it later cut it off from the social and political field in which it originated.

In 1993, an article by Sarah Chinski entitled “Silence of the Fish: The Local versus the Universal in the Israeli Discourse on Art” was published in the journal Theory and Criticism. The article criticized the narcissistic banner-waving of the self-pitying Tel Avivan.” Against this image of self-pity, Chinski juxtaposed the political reality that gave birth to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. “The ‘dispossessed sabra’,” writes Chinski, “has been so focused on self-pity for his imaginary losses, he hasn’t noticed that in his name massive expulsions of huge numbers of people have taken place throughout all the glorious history of the Palmach and the youth movement he has created in his heart.“[26]

References

- ↑ Gideon Ofrat, “Israeli Art and the Jewish Tradition.” [in Hebrew]

- ↑ The photography of Michal Heiman, for example, documented Raffi’s wanderings around the city and presented him at his most typical. Another artist, Doron Rabina, described the earthy image of this artist: “End of a summer day at Hamidrasha. Raffi walks into the cafeteria, sweat streaming down his face, his shirt glued to his back with sweat. I couldn’t help thinking, “This is the Maestro.” See: Doron Rabina, “Drawing Proper,” Hamidrasha, 2 (1999): 127. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ This format became a permanent part of the scene primarily toward the end of the 1980s.

- ↑ Sarit Shapira, “This isn’t a Cactus, it’s a Geranium,” (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 2003) 18-20. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Michal Na’aman, “Please Don’t Read What’s Written Here,” Hamidrasha 2 (1999): 104. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Ruti Direktor, “A Little Bit Guru, a Little Bit Fake,” Hadashot [News] (April 4, 1986). [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Sarah Breitberg-Semel, “Want of Matter as a Sign of Excellence in Israeli Art,” Hamidrasha 2 (1999):267. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Sarah Breitberg-Semel, “Michal Na’aman: What Has She Done Here?” Studio 40(January 1993): 48. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Kits of ready-made stick-on letters intended for various graphic purposes.

- ↑ Sarah Breitberg-Semel, “How Much Happiness Can Grow Out of This Reduction: a Conversation with Nahum Tevet,” Studio 91 (March 1998): 24. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ This relationship is clearer in Tevet’s later installations, such as his series of works called “Painting Lessons.”

- ↑ Training Young Artists,” Muzot [Muses] 5/6 (February 1989): 20. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Roee Rosen, “The Birth of Oil and the Life of the Machine,” Studio 94 (June–July 1998):43. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Gideon Efrat, Dorit Lavita, and Benjamin Tammuz, The Story of Israeli Art (Tel Aviv : Masada Publishers, 1980), 305-310. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Sarah Breitberg-Semel, “Want of Matter as a Sign of Excellence in Israeli Art,” Hamidrasha 2 (1999):258. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Yair Garbuz, “About Raffi: Color patch, Crown, Catchup, Love,” Hamidrasha 2 (1999):37. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Yair Garbuz, “About Raffi: Color patch, Crown. Catchup, Love,” Hamidrasha 2 (1999):39-43. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Ariella Azoulay, “The Place of Art,” Studio 4 (January 1993):9-11. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Exceptions were the installation of Nahum Tevet, and the objects of Pinchas Cohen Gan, Tsibi Geva, and Michael Druks, whose work, in spite of its “three-dimensionality,” included a clear affinity to painting.

- ↑ Itamar Levy, “There are No Child Prodigies, Yediot Ahronoth (March 28, 1986). [in Hebrew]

- ↑ ”Peulah” (activity) was the previous Hebrew term for “installation.”

- ↑ Ariella Azoulay, Exercising Art: a Critique of the Economics of Museum Curation (Tel Aviv: Kibbutz Hameuhad, 1999), 163-164. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ In: Ariella Azoulay, Exercising Art: a Critique of the Economics of Museum Curation (Tel Aviv: Kibbutz Hameuhad, 1999), 136. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Ellen Ginton, The Eyes of the Nation. Visual Art in a Country without Boundaries (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum, 1998) [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Sarah Breitberg-Semel, “Want of Matter,” in: Haim Losky, ed. The City, Utopia, and Israeli Society (Tel Aviv: 1989), 108. [in Hebrew]

- ↑ Sarah Chinski, “Silence of the Fish: The Local versus the Universal in the Israeli Discourse on Art,” Theory and Criticism 4 (Autumn 1993):105-122. [in Hebrew]