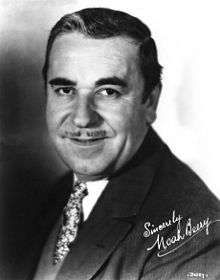

Wallace Beery

| Wallace Beery | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Born |

Wallace Fitzgerald Beery April 1, 1885 Clay County, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died |

April 15, 1949 (aged 64) Beverly Hills, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Heart attack |

| Occupation | Actor, singer, director |

| Years active | 1913–1949 |

| Spouse(s) |

Gloria Swanson (m. 1916–1919; divorced) Rita Gilman (m. 1924–1939; divorced) 1 child |

| Children | Carol Ann (adopted) |

Wallace Fitzgerald Beery (April 1, 1885 – April 15, 1949) was an American film actor.[1] He is best known for his portrayal of Bill in Min and Bill opposite Marie Dressler, as Long John Silver in Treasure Island, as Pancho Villa in Viva Villa!, and his titular role in The Champ, for which he won the Academy Award for Best Actor. Beery appeared in some 250 movies during a 36-year career. His contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer stipulated in 1932 that he be paid $1 more than any other contract player at the studio, making him the highest paid actor in the world. He was the brother of actor Noah Beery Sr. and uncle of actor Noah Beery Jr.

For his contributions to the motion picture industry, Beery has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 7001 Hollywood Blvd.[2] which places him in a select group of fewer than a hundred male actors in Hollywood history to receive both an Academy Award and a Walk of Fame star.

Early life

Beery was born in Clay County, Missouri, near Smithville.[3] The youngest of three sons born to Noah Webster Beery (January 11, 1856 Platte County, Missouri – May 19, 1937 Los Angeles County, California) and Frances Margaret Fitzgerald (1859 Ridgely, Missouri – April 9, 1931 Los Angeles County, California), he and his brothers William C. Beery[4] and Noah Beery became Hollywood actors. The Beery family left the farm in the 1890s and moved to nearby Kansas City, Missouri, where the father was a police officer.

Wallace Beery attended the Chase School in Kansas City and took piano lessons as well, but showed little love for academic matters. He ran away from home twice, the first time returning after a short time, quitting school and working in the Kansas City train yards as an engine wiper.[3] Beery ran away from home a second time at age 16, and joined the Ringling Brothers Circus as an assistant elephant trainer. He left two years later, after being clawed by a leopard.

Career

_-_Wallace_Beery.jpg)

Wallace Beery joined his brother Noah in New York City in 1904, finding work in comic opera as a baritone and began to appear on Broadway as well as Summer stock theatre. His most notable early role came in 1907 when he starred in The Yankee Tourist to good reviews. In 1913, he moved to Chicago to work for Essanay Studios, cast as Sweedie, The Swedish Maid, a masculine character in drag. Later, he worked for the Essanay Studios location in Niles, California.

In 1915, Beery starred with his wife Gloria Swanson in Sweedie Goes to College. This marriage did not survive his drinking and abuse. Beery began playing villains, and in 1917 portrayed Pancho Villa in Patria at a time when Villa was still active in Mexico. Beery reprised the role seventeen years later in one of MGM's biggest hits.

Wallace Beery's notable silent films include Arthur Conan Doyle's dinosaur epic The Lost World (1925; as Professor Challenger), Robin Hood with Douglas Fairbanks (Beery played King Richard the Lionheart in this film and a sequel the following year called Richard the Lion-Hearted), The Last of the Mohicans (1920), The Round-Up (1920; with Roscoe Arbuckle), Old Ironsides (1926), Now We're in the Air (1927), The Usual Way (1913), Casey at the Bat (1927), and Beggars of Life (1928) with Louise Brooks.

Transition to sound

_trailer_1.jpg)

Beery's powerful basso voice and gruff, deliberate drawl soon became assets when Irving Thalberg hired him under contract to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as a character actor during the dawn of the sound film era.

Beery played the savage convict "Butch", a role originally intended for Lon Chaney Sr. in the highly successful 1930 prison film The Big House, for which he was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor. The same year, he made Min and Bill (opposite Marie Dressler), the movie that vaulted him into the box office first rank.

In 1931 he starred in The Champ, and shared the Best Actor Oscar with Fredric March. Though March received one vote more than Beery, Academy rules at the time—since rescinded—defined results within one vote of each other as "ties".[5] In 1934 he played the role of Long John Silver in Treasure Island, and received a gold medal from the Venice Film Festival for his performance as Pancho Villa in Viva Villa! (1934) with Fay Wray. )

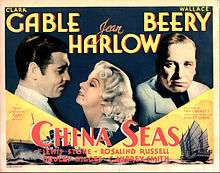

Other Beery films include Billy the Kid (1930) with Johnny Mack Brown, The Secret Six (1931) with Jean Harlow and Clark Gable, Hell Divers (1931) with Gable, Grand Hotel (1932) with Greta Garbo and Joan Crawford, Tugboat Annie (1933) with Dressler, Dinner at Eight (1933) opposite Harlow, The Bowery with George Raft, Fay Wray, and Pert Kelton that same year, China Seas (1935) with Gable and Harlow, and Eugene O'Neill's Ah, Wilderness! (1935) in the role of a drunken uncle later played on Broadway by Jackie Gleason in a musical comedy version. During the 1930s Beery was one of Hollywood's Top 10 box office stars; it was during the early part of this period, in 1932, that his contract with MGM stipulated that he be paid a dollar more than any other contract player at the studio, making him the world's highest paid actor.

He starred in several comedies with Marie Dressler and later, after Dressler's death, Marjorie Main, but his career began to decline in his last decade. In 1943 his brother Noah Beery Sr. appeared with him in the war-time propaganda film Salute to the Marines, followed by Bad Bascomb (1946) and The Mighty McGurk (1947). He remained top-billed and none of Beery's films during the sound era lost money at the box office; his movies were particularly popular in the Southern regions of the United States, especially small towns and cities.

Personal life

.png)

.png)

Beery's first wife was actress Gloria Swanson; the two performed onscreen together. Although Beery had enjoyed popularity with his Sweedie shorts, his career had taken a dip, and during the marriage to Swanson, he relied on her as a breadwinner. According to Swanson's autobiography, Beery raped her on their wedding night, and later tricked her into swallowing an abortifacient when she was pregnant, which caused her to lose their child.[6] Beery's second wife was Rita Gilman. They adopted Carol Ann, daughter of Rita Beery's cousin. Both marriages ended in divorce.

In December 1939, the unmarried Beery adopted a seven-month-old infant girl Phyllis Ann.[7] Phyllis appeared in MGM publicity photos when adopted, but was never mentioned again.[8] Beery told the press he had taken the girl in from a single mother, recently divorced, but he had filed no official adoption papers.[9]

Beery was considered misanthropic and difficult to work with by many of his colleagues. Mickey Rooney related in his autobiography that Howard Strickling, MGM's head of publicity, once went to Louis B. Mayer to complain that Beery was stealing props off of the studio's sets. "And that wasn't all," Rooney continued. "He went on for some minutes about the trouble that Beery was always causing him ... Mayer sighed and said, 'Yes, Howard, Beery's a son of a bitch. But he's our son of a bitch.' Strickling got the point. A family has to be tolerant of its black sheep, particularly if they brought a lot of money into the family fold, which Beery certainly did."[10]

Child actors, in particular, recalled unpleasant encounters with Beery. Jackie Cooper, who made several films with him early in his career, called him "a big disappointment", and accused him of upstaging, and other attempts to undermine his performances, out of what Cooper presumed was jealousy.[11] He recalled impulsively throwing his arms around Beery after one especially heartfelt scene, only to be gruffly pushed away.[12] Child actress Margaret O'Brien claimed that she had to be protected by crew members from Beery's insistence on constantly pinching her.[13]

Rooney remained an exception to the general negative attitude among child actors. In his memoir he described Beery as "... a lovable, shambling kind of guy who never seemed to know that his shirttail belonged inside his pants, but always knew when a little kid actor needed a smile and a wink or a word of encouragement." He did concede that "not everyone loved [Beery] as much as I did."[14] Beery, by contrast, described Rooney as a "brat", but a "fine actor".[15]

Beery owned and flew his own planes,[16] one a Howard DGA-11. On April 15, 1933 he was commissioned a Lieutenant Commander in the United States Navy Reserve at NRAB Long Beach.[17] One of his proudest achievements was catching the largest black sea bass in the world off Santa Catalina Island in 1916, a record that stood for 35 years.

A noteworthy episode in Beery's life is chronicled in the fifth episode of Ken Burns' documentary The National Parks: America's Best Idea: In 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order creating Jackson Hole National Monument to protect the land adjoining the Grand Tetons in Wyoming. Local ranchers, outraged at the loss of grazing lands, compared FDR's action to Hitler's taking of Austria. Led by an aging Beery, they protested by herding 500 cattle across the monument lands without a permit.[18]

Death

Wallace Beery died at his Beverly Hills, California home of a heart attack on April 15, 1949. He was interred at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. The inscription on his grave reads, "NO MAN IS INDISPENSABLE BUT SOME ARE IRREPLACEABLE." When Mickey Rooney's father died less than a year later, Rooney arranged to have him buried next to his old friend. "I thought it was fitting that these two comedians should rest in peace, side by side," he wrote.[19]

For his contributions to the film industry, Wallace Beery was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 7001 Hollywood Boulevard.

Legacy

Beery is mentioned in the film Barton Fink, in which the lead character has been hired to write a wrestling screenplay to star Beery.[20]

Selected filmography

.png)

.png)

- His Athletic Wife (1913)

- A series of at least 29 Sweedie-films starting with Sweedie the Swatter, released 13 July 1914

- In and Out (1914)

- The Ups and Downs (1914)

- Cheering a Husband (1914)

- Madame Double X (1914)

- Ain't It the Truth (1915)

- Two Hearts That Beat as Ten (1915) with Ben Turpin

- The Fable of the Roistering Blades (1915)

- The Slim Princess (1915) with Francis X. Bushman

- The Broken Pledge (1915) with Gloria Swanson

- A Dash of Courage (1916) with Gloria Swanson

- The Little American (1917) with Mary Pickford

- Maggie's First False Step (1917)

- Teddy at the Throttle (1917)

- The Unpardonable Sin (1919)

- The Love Burglar (1919) with Wallace Reid and Anna Q. Nilsson

- Victory (1919) with Jack Holt and Lon Chaney Sr.

- Behind the Door (1919) with Hobart Bosworth and Jane Novak

- The Life Line (1919) with Jack Holt

- 813 (1920)

- The Virgin of Stamboul (1920; directed by Tod Browning)

- The Mollycoddle (1920) with Douglas Fairbanks

- The Round-Up (1920) with Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle

- The Last of the Mohicans (1920)

- The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) with Rudolph Valentino

- A Tale of Two Worlds (1921 Goldwyn)(*extant; Library of Congress)

- Sleeping Acres (1921)

- Wild Honey (1922) with Priscilla Dean and Noah Beery Sr.

- I Am the Law (1922) with Noah Beery

- Robin Hood (1922) with Douglas Fairbanks

- A Blind Bargain (1922) with Lon Chaney Sr.

- The Flame of Life (1923)

- The Spanish Dancer (1923) with Pola Negri

- Stormswept (1923) with Noah Beery Sr.

- Ashes of Vengeance (1923) with Norma Talmadge

- Drifting (1923) with Priscilla Dean and Anna May Wong

- Bavu (1923)

- Three Ages (1923) with Buster Keaton

- The Eternal Struggle (1923)

- White Tiger (1923; directed by Tod Browning)

- Richard the Lion-Hearted (1923; sequel to 1922's Robin Hood)

- The Drums of Jeopardy (1923)

- The Sea Hawk (1924)

- The Lost World (1925; Arthur Conan Doyle dinosaur epic in which Beery portrayed Professor Challenger) with Lewis Stone (and Doyle himself in a frontispiece)

- The Devil's Cargo (1925)

- The Night Club (1925) with Raymond Griffith and Vera Reynolds

- Pony Express (1925) with Betty Compson and George Bancroft

- The Wanderer (1925) with Greta Nissen and Tyrone Power Sr.

- Behind the Front (1926) with Raymond Hatton

- Volcano! (1926)

- Old Ironsides (1926) with Charles Farrell and George Bancroft

- Casey at the Bat (1927) with Ford Sterling and ZaSu Pitts

- Fireman, Save My Child (1927) with Raymond Hatton

- Now We're in the Air (1927) with Louise Brooks (lost film)

- Beggars of Life (1928) with Louise Brooks and Richard Arlen

- Wife Savers (1928) with Raymond Hatton and ZaSu Pitts (lost film)

- Chinatown Nights (1929) with Warner Oland and Jack Oakie

- The Big House (1930) with Chester Morris, Lewis Stone, and Robert Montgomery

- Billy the Kid (1930; widescreen) with Johnny Mack Brown (billed as "John Mack Brown")

- Way for a Sailor (1930) with John Gilbert

- A Lady's Morals (1930; as P.T. Barnum)

- Min and Bill (1930) with Marie Dressler

- The Stolen Jools (1931; 20-minute ensemble short) with Edward G. Robinson and Buster Keaton

- The Secret Six (1931) with Jean Harlow and Clark Gable

- The Champ (1931; Oscar-winning performance) with Jackie Cooper

- Hell Divers (1931; early military planes) with Clark Gable

- Grand Hotel (1932) with Greta Garbo, John Barrymore, Lionel Barrymore and Joan Crawford

- Flesh (1932; as a wrestler, directed by an uncredited John Ford)

- Dinner at Eight (1933) with Marie Dressler, Lionel Barrymore, and Jean Harlow

- The Bowery (1933) with George Raft, Jackie Cooper, Fay Wray and Pert Kelton

- Viva Villa! (1934; as Pancho Villa) with Leo Carrillo, Stu Erwin and Fay Wray (shot on location in Mexico)

- Tugboat Annie (1934) with Marie Dressler, Robert Young and Maureen O'Sullivan

- Treasure Island (1934; as Long John Silver) with Jackie Cooper, Lionel Barrymore and Lewis Stone

- The Mighty Barnum (1934; as P.T. Barnum again) with Adolphe Menjou

- West Point of the Air (1935) with Robert Young, Maureen O'Sullivan, Rosalind Russell, and Robert Taylor

- China Seas (1935) with Clark Gable, Jean Harlow, Lewis Stone, and Robert Benchley

- O'Shaughnessy's Boy (1935) with Jackie Cooper

- Ah, Wilderness! (1935) with Lionel Barrymore, Aline MacMahon, and Mickey Rooney

- A Message to Garcia (1936) with Barbara Stanwyck and Alan Hale Sr.

- Old Hutch (1936)

- The Good Old Soak (1937) with Betty Furness and Ted Healy

- Slave Ship (1937) with Warner Baxter (first-billed) and Mickey Rooney

- The Bad Man of Brimstone (1937) with Noah Beery Sr.

- Port of Seven Seas (1938; written by Preston Sturges and directed by James Whale) with Maureen O'Sullivan

- Stablemates (1938) with Mickey Rooney

- Stand Up and Fight (1939) with Robert Taylor and Charles Bickford

- Sergeant Madden (1939; directed by Josef von Sternberg) with Laraine Day

- Thunder Afloat (1939) with Chester Morris

- The Man from Dakota (1940) with Dolores del Río

- 20 Mule Team (1940) with Anne Baxter and Noah Beery Jr.

- Wyoming (1940) with Ann Rutherford

- The Bad Man (1941) with Lionel Barrymore, Laraine Day, and Ronald Reagan

- Barnacle Bill (1941) with Marjorie Main

- The Bugle Sounds (1942) with Marjorie Main, Lewis Stone, and George Bancroft

- Jackass Mail (1942) with Marjorie Main

- Salute to the Marines (1943, in color) with Noah Beery Sr.

- Rationing (1944) with Marjorie Main

- Barbary Coast Gent (1944) with Chill Wills and Noah Beery Sr.

- This Man's Navy (1945) with Noah Beery Sr.

- Bad Bascomb (1946) with Margaret O'Brien and Marjorie Main

- The Mighty McGurk (1947) with Dean Stockwell and Edward Arnold

- Alias a Gentleman (1948) with Gladys George and Sheldon Leonard

- A Date with Judy (1948) with Jane Powell, Elizabeth Taylor and Carmen Miranda

- Big Jack (1949) with Richard Conte, Marjorie Main, and Edward Arnold

Awards and nominations

| Year | Award | Film | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | Academy Award for Best Actor | The Big House | Nominated |

| 1932 | Academy Award for Best Actor | The Champ | Won ("Tied" with Fredric March for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde although in reality March received one more vote than Beery.) |

| 1934 | Venice Film Festival Award for Best Actor | Viva Villa! | Won |

References

- ↑ Obituary Variety, April 20, 1949.

- ↑ Walk of Fame Stars-Wallace Beery

- 1 2 Dictionary of Missouri Biography, Lawrence O. Christensen, University of Missouri Press, 1999.

- ↑ William C. Beery; findagrave.com

- ↑ History of the Academy Awards: The Fifth Academy Awards, 1931/32. About.com archive. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ↑ Swanson, Gloria (1980). Swanson on Swanson. Random House. pp. 69–75. ISBN 0-394-50662-6.

- ↑ Milestones, Dec. 4, 1939, Time.com

- ↑ A Certain Cinema, Acertaincinema.com

- ↑ Beery Will Add To Adopted Family, Google News

- ↑ Rooney, M. Life is Too Short. Villard Books (1991), p. 77. ISBN 0679401954.

- ↑ Cooper, Jackie. Please Don't Shoot My Dog. Morrow, 1980, pp. 54-61. ISBN 0-688-03659-7

- ↑ Bergan, R (May 5, 2011). Jackie Cooper Obituary. The Guardian archive. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ↑ Private Screenings: Child Stars|date=March 2009

- ↑ Rooney, M. Life is Too Short. Villard Books (1991), pp. 76-7. ISBN 0679401954.

- ↑ Marx, A. The Nine Lives of Mickey Rooney. Stein and Day (1986), p. 68. ISBN 0812830563.

- ↑ Dmairfield.com

- ↑ Heiser, Wayne H., "U.S. Naval and Marine Corps Reserve Aviation V. I, 1916–1942." p.78.

- ↑ Episode Five: 1933–1945 Great Nature

- ↑ Rooney, M. Life is Too Short. Villard Books (1991), p. 239. ISBN 0679401954.

- ↑ Rafferty, Terrence (July 27, 2003). "FILM; He's Nobody Important, Really. Just a Movie Writer.". The New York Times.

Further reading

- Wise, James. Stars in Blue: Movie Actors in America's Sea Services. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997. ISBN 1557509379 OCLC 36824724

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wallace Beery. |

- Wallace Beery at the Internet Movie Database

- AllMovie.com/ biography

- Wallace Beery at the Internet Broadway Database

- Wallace Beery and Gloria Swanson's Marriage

- Photographs of Wallace Beery