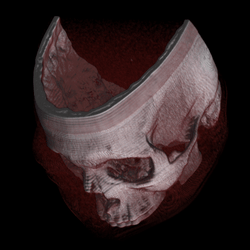

Volume rendering

In scientific visualization and computer graphics, volume rendering is a set of techniques used to display a 2D projection of a 3D discretely sampled data set, typically a 3D scalar field.

A typical 3D data set is a group of 2D slice images acquired by a CT, MRI, or MicroCT scanner. Usually these are acquired in a regular pattern (e.g., one slice every millimeter) and usually have a regular number of image pixels in a regular pattern. This is an example of a regular volumetric grid, with each volume element, or voxel represented by a single value that is obtained by sampling the immediate area surrounding the voxel.

To render a 2D projection of the 3D data set, one first needs to define a camera in space relative to the volume. Also, one needs to define the opacity and color of every voxel. This is usually defined using an RGBA (for red, green, blue, alpha) transfer function that defines the RGBA value for every possible voxel value.

For example, a volume may be viewed by extracting isosurfaces (surfaces of equal values) from the volume and rendering them as polygonal meshes or by rendering the volume directly as a block of data. The marching cubes algorithm is a common technique for extracting an isosurface from volume data. Direct volume rendering is a computationally intensive task that may be performed in several ways.

Direct volume rendering

A direct volume renderer[1][2] requires every sample value to be mapped to opacity and a color. This is done with a "transfer function" which can be a simple ramp, a piecewise linear function or an arbitrary table. Once converted to an RGBA (for red, green, blue, alpha) value, the composed RGBA result is projected on corresponding pixel of the frame buffer. The way this is done depends on the rendering technique.

A combination of these techniques is possible. For instance, a shear warp implementation could use texturing hardware to draw the aligned slices in the off-screen buffer.

Volume ray casting

The technique of volume ray casting can be derived directly from the rendering equation. It provides results of very high quality, usually considered to provide the best image quality. Volume ray casting is classified as image based volume rendering technique, as the computation emanates from the output image, not the input volume data as is the case with object based techniques. In this technique, a ray is generated for each desired image pixel. Using a simple camera model, the ray starts at the center of projection of the camera (usually the eye point) and passes through the image pixel on the imaginary image plane floating in between the camera and the volume to be rendered. The ray is clipped by the boundaries of the volume in order to save time. Then the ray is sampled at regular or adaptive intervals throughout the volume. The data is interpolated at each sample point, the transfer function applied to form an RGBA sample, the sample is composited onto the accumulated RGBA of the ray, and the process repeated until the ray exits the volume. The RGBA color is converted to an RGB color and deposited in the corresponding image pixel. The process is repeated for every pixel on the screen to form the completed image.

Splatting

This is a technique which trades quality for speed. Here, every volume element is splatted, as Lee Westover said, like a snow ball, on to the viewing surface in back to front order. These splats are rendered as disks whose properties (color and transparency) vary diametrically in normal (Gaussian) manner. Flat disks and those with other kinds of property distribution are also used depending on the application.[3][4]

Shear warp

The shear warp approach to volume rendering was developed by Cameron and Undrill, popularized by Philippe Lacroute and Marc Levoy.[5] In this technique, the viewing transformation is transformed such that the nearest face of the volume becomes axis aligned with an off-screen image buffer with a fixed scale of voxels to pixels. The volume is then rendered into this buffer using the far more favorable memory alignment and fixed scaling and blending factors. Once all slices of the volume have been rendered, the buffer is then warped into the desired orientation and scaled in the displayed image.

This technique is relatively fast in software at the cost of less accurate sampling and potentially worse image quality compared to ray casting. There is memory overhead for storing multiple copies of the volume, for the ability to have near axis aligned volumes. This overhead can be mitigated using run length encoding.

Texture-based volume rendering

Many 3D graphics systems use texture mapping to apply images, or textures, to geometric objects. Commodity PC graphics cards are fast at texturing and can efficiently render slices of a 3D volume, with real time interaction capabilities. Workstation GPUs are even faster, and are the basis for much of the production volume visualization used in medical imaging, oil and gas, and other markets (2007). In earlier years, dedicated 3D texture mapping systems were used on graphics systems such as Silicon Graphics InfiniteReality, HP Visualize FX graphics accelerator, and others. This technique was first described by Bill Hibbard and Dave Santek.[6]

These slices can either be aligned with the volume and rendered at an angle to the viewer, or aligned with the viewing plane and sampled from unaligned slices through the volume. Graphics hardware support for 3D textures is needed for the second technique.

Volume aligned texturing produces images of reasonable quality, though there is often a noticeable transition when the volume is rotated.

Maximum intensity projection

As opposed to direct volume rendering, which requires every sample value to be mapped to opacity and a color, maximum intensity projection picks out and projects only the voxels with maximum intensity that fall in the way of parallel rays traced from the viewpoint to the plane of projection.

This technique is computationally fast, but the 2D results do not provide a good sense of depth of the original data. To improve the sense of 3D, animations are usually rendered of several MIP frames in which the viewpoint is slightly changed from one to the other, thus creating the illusion of rotation. This helps the viewer's perception to find the relative 3D positions of the object components. This implies that two MIP renderings from opposite viewpoints are symmetrical images, which makes it impossible for the viewer to distinguish between left or right, front or back and even if the object is rotating clockwise or counterclockwise even though it makes a significant difference for the volume being rendered.

MIP imaging was invented for use in nuclear medicine by Jerold Wallis, MD, in 1988, and subsequently published in IEEE Transactions in Medical Imaging.[7][8][9]

Surprisingly, an easy improvement to MIP is Local maximum intensity projection. In this technique we don't take the global maximum value, but the first maximum value that is above a certain threshold. Because - in general - we can terminate the ray earlier this technique is faster and also gives somehow better results as it approximates occlusion.[10]

Hardware-accelerated volume rendering

Due to the extremely parallel nature of direct volume rendering, special purpose volume rendering hardware was a rich research topic before GPU volume rendering became fast enough. The most widely cited technology was VolumePro,[11] which used high memory bandwidth and brute force to render using the ray casting algorithm.

A recently exploited technique to accelerate traditional volume rendering algorithms such as ray-casting is the use of modern graphics cards. Starting with the programmable pixel shaders, people recognized the power of parallel operations on multiple pixels and began to perform general-purpose computing on (the) graphics processing units (GPGPU). The pixel shaders are able to read and write randomly from video memory and perform some basic mathematical and logical calculations. These SIMD processors were used to perform general calculations such as rendering polygons and signal processing. In recent GPU generations, the pixel shaders now are able to function as MIMD processors (now able to independently branch) utilizing up to 1 GB of texture memory with floating point formats. With such power, virtually any algorithm with steps that can be performed in parallel, such as volume ray casting or tomographic reconstruction, can be performed with tremendous acceleration. The programmable pixel shaders can be used to simulate variations in the characteristics of lighting, shadow, reflection, emissive color and so forth. Such simulations can be written using high level shading languages.

Optimization techniques

The primary goal of optimization is to skip as much of the volume as possible. A typical medical data set can be 1 GB in size. To render that at 30 frame/s requires an extremely fast memory bus. Skipping voxels means that less information needs to be processed.

Empty space skipping

Often, a volume rendering system will have a system for identifying regions of the volume containing no visible material. This information can be used to avoid rendering these transparent regions.[12]

Early ray termination

This is a technique used when the volume is rendered in front to back order. For a ray through a pixel, once sufficient dense material has been encountered, further samples will make no significant contribution to the pixel and so may be neglected.

Octree and BSP space subdivision

The use of hierarchical structures such as octree and BSP-tree could be very helpful for both compression of volume data and speed optimization of volumetric ray casting process.

Volume segmentation

By sectioning out large portions of the volume that one considers uninteresting before rendering, the amount of calculations that have to be made by ray casting or texture blending can be significantly reduced. This reduction can be as much as from O(n) to O(log n) for n sequentially indexed voxels. Volume segmentation also has significant performance benefits for other ray tracing algorithms.

Multiple and adaptive resolution representation

By representing less interesting regions of the volume in a coarser resolution, the data input overhead can be reduced. On closer observation, the data in these regions can be populated either by reading from memory or disk, or by interpolation. The coarser resolution volume is resampled to a smaller size in the same way as a 2D mipmap image is created from the original. These smaller volume are also used by themselves while rotating the volume to a new orientation.

Pre-integrated volume rendering

Pre-integrated volume rendering[13] is a method that can reduce sampling artifacts by pre-computing much of the required data. It is especially useful in hardware-accelerated applications[14][15] because it improves quality without a large performance impact. Unlike most other optimizations, this does not skip voxels. Rather it reduces the number of samples needed to accurately display a region of voxels. The idea is to render the intervals between the samples instead of the samples themselves. This technique captures rapidly changing material, for example the transition from muscle to bone with much less computation.

Image-based meshing

Image-based meshing is the automated process of creating computer models from 3D image data (such as MRI, CT, Industrial CT or microtomography) for computational analysis and design, e.g. CAD, CFD, and FEA.

Temporal reuse of voxels

For a complete display view, only one voxel per pixel (the front one) is required to be shown (although more can be used for smoothing the image), if animation is needed, the front voxels to be shown can be cached and their location relative to the camera can be recalculated as it moves. Where display voxels become too far apart to cover all the pixels, new front voxels can be found by ray casting or similar, and where two voxels are in one pixel, the front one can be kept.

See also

- Isosurface, a surface that represents points of a constant value (e.g. pressure, temperature, velocity, density) within a volume of space

- Flow visualization, a technique for the visualization of vector fields

- Volume mesh, a polygonal representation of the interior volume of an object

Software

- Open source

- 3D Slicer – a software package for scientific visualization and image analysis

- ClearVolume – a GPU ray-casting based, live 3D visualization library designed for high-end volumetric light sheet microscopes.

- ImageVis3D – a GPU volume slicing and ray casting implementation

- ParaView – a coss-platform data analysis and visualization application. ParaView users can quickly build visualizations to analyze their data using qualitative and quantitative techniques.

- Vaa3D – a 3D, 4D and 5D volume rendering and image analysis platform for gigabytes and terabytes of large images (based on OpenGL) especially in the microscopy image field. Also cross-platform with Mac, Windows, and Linux versions. Include a comprehensive plugin interface and 100 plugins for image analysis. Also render multiple types of surface objects.

- VisIt – a cross-platform interactive parallel visualization and graphical analysis tool for viewing scientific data.

- Volume cartography – an open source software used in recovering the En-Gedi Scroll.

- Voreen – a cross-platform rapid application development framework for the interactive visualization and analysis of multi-modal volumetric data sets. It provides GPU-based volume rendering and data analysis techniques

- Commercial

- Ambivu 3D Workstation – a medical imaging workstation that offers a range of volume rendering modes (based on OpenGL)

- Amira – a 3D visualization and analysis software for scientists and researchers (in life sciences and biomedical)

- Avizo – a 3D visualization and analysis software for scientists and engineers

- MeVisLab – cross-platform software for medical image processing and visualization (based on OpenGL and Open Inventor)

- Open Inventor – a high-level 3D API for 3D graphics software development (C++, .NET, Java)

- ScanIP – an image processing and image-based meshing platform that can render scan data (MRI, CT, Micro-CT...) in 3D directly after import.

- tomviz – a 3D visualization platform for scientists and researchers that can utilize Python scripts for advanced 3D data processing.

- VoluMedic – a volume slicing and rendering software

References

- ↑ Marc Levoy, "Display of Surfaces from Volume Data", IEEE CG&A, May 1988. Archive of Paper

- ↑ Drebin, Robert A.; Carpenter, Loren; Hanrahan, Pat (1988). "Volume rendering". ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics. 22 (4): 65. doi:10.1145/378456.378484. Drebin, Robert A.; Carpenter, Loren; Hanrahan, Pat (1988). "Proceedings of the 15th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques - SIGGRAPH '88": 65. doi:10.1145/54852.378484. ISBN 0897912756.

- ↑ Westover, Lee Alan (July 1991). "SPLATTING: A Parallel, Feed-Forward Volume Rendering Algorithm" (PDF). Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ↑ Huang, Jian (Spring 2002). "Splatting" (PPT). Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ Lacroute, Philippe; Levoy, Marc (1994-01-01). "Fast Volume Rendering Using a Shear-warp Factorization of the Viewing Transformation". Proceedings of the 21st Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques. SIGGRAPH '94. New York, NY, USA: ACM: 451–458. doi:10.1145/192161.192283. ISBN 0897916670.

- ↑ Hibbard W., Santek D., "Interactivity is the key", Chapel Hill Workshop on Volume Visualization, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1989, pp. 39–43.

- ↑ Wallis, J.W.; Miller, T.R.; Lerner, C.A.; Kleerup, E.C. (1989). "Three-dimensional display in nuclear medicine". IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 8 (4): 297–303. doi:10.1109/42.41482. PMID 18230529.

- ↑ Wallis, JW; Miller, TR (1 August 1990). "Volume rendering in three-dimensional display of SPECT images". Journal of nuclear medicine. 31 (8): 1421–8. PMID 2384811.

- ↑ Wallis, JW; Miller, TR (March 1991). "Three-dimensional display in nuclear medicine and radiology". Journal of nuclear medicine. 32 (3): 534–46. PMID 2005466.

- ↑ Sato, Yoshinobu; Shiraga, Nobuyuki; Nakajima, Shin; Tamura, Shinichi; Kikinis, Ron. "Local Maximum Intensity Projection (LMIP". Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 22 (6): 912–917. doi:10.1097/00004728-199811000-00014.

- ↑ Pfister, Hanspeter; Hardenbergh, Jan; Knittel, Jim; Lauer, Hugh; Seiler, Larry (1999). "The VolumePro real-time ray-casting system". Proceedings of the 26th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques - SIGGRAPH '99: 251. doi:10.1145/311535.311563. ISBN 0201485605.

- ↑ Sherbondy A., Houston M., Napel S.: Fast volume segmentation with simultaneous visualization using programmable graphics hardware. In Proceedings of IEEE Visualization (2003), pp. 171–176.

- ↑ Max N., Hanrahan P., Crawfis R.: Area and volume coherence for efficient visualization of 3D scalar functions. In Computer Graphics (San Diego Workshop on Volume Visualization, 1990) vol. 24, pp. 27–33.

- ↑ Engel, Klaus; Kraus, Martin; Ertl, Thomas (2001). "High-quality pre-integrated volume rendering using hardware-accelerated pixel shading". Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH/EUROGRAPHICS workshop on Graphics hardware - HWWS '01: 9. doi:10.1145/383507.383515. ISBN 158113407X.

- ↑ Lum E., Wilson B., Ma K.: High-Quality Lighting and Efficient Pre-Integration for Volume Rendering. In Eurographics/IEEE Symposium on Visualization 2004.

Further reading

- Volume Rendering, Volume Rendering Basics Tutorial by Ph.D. Ömer Cengiz ÇELEBİ

- Barthold Lichtenbelt, Randy Crane, Shaz Naqvi, Introduction to Volume Rendering (Hewlett-Packard Professional Books), Hewlett-Packard Company 1998.

- Peng H., Ruan, Z, Long, F, Simpson, JH, Myers, EW: V3D enables real-time 3D visualization and quantitative analysis of large-scale biological image data sets. Nature Biotechnology, 2010 doi:10.1038/nbt.1612 Volume Rendering of large high-dimensional image data.

- Daniel Weiskopf (2006). GPU-Based Interactive Visualization Techniques. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-33263-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Volume rendering. |

- VolumeRendererUnity – a private volume renderer in unity as a web application by Christian Petry

- VRender: Pixar's GPU based Volume Renderer – video presentation by Florian Hecht (slides)

- CHAI3D – a C++ framework for 3D graphics and haptics rendering of surface and volume models. (Stanford University)