United States v. Huck Mfg. Co.

United States v. Huck Mfg. Co., 382 U.S. 197 (1965), is the most recent patent-license price-fixing case to reach the United States Supreme Court. It was completely inconclusive, because the Court split 4–4 and affirmed the decision of the lower court without opinion. [1]

Background

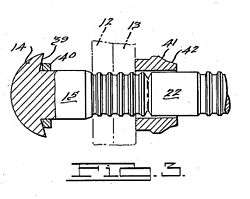

Huck Mfg. Co. and Townsend Co. were the principal U.S. manufacturers of lockbolts. A lockbolt is a two-part metal fastening device used to join together permanently two or more pieces of metal. They are used in the manufacture of aircraft, and also ships, railroad cars, and other vehicles. Huck owns United States Patents Nos. 2,531,048 and 2,531,049 on lockbolts, invented by Louis Huck, issued in 1950. After patent infringement disputes, in 1954 Huck licensed Townsend on the following terms:

- The license to Townsend is exclusive for two years and then nonexclusive, with a 5% royalty.

- Townsend grants Huck a non-exclusive royalty-free license with a right to sublicense if Townsend acquires any patent rights on lockbolts.

- During the two-year exclusive period Townsend shall maintain at least Huck's prices on lockbolts per Huck's published price schedule.

- In addition to the written agreement, a verbal side agreement between defendants Huck and Townsend provided that Huck would not grant licenses under the lockbolt patents to others so long as Townsend maintained Huck's established prices.[2]

Although Huck and Townsend met from time to time since 1954, they did not meet "for the purpose of fixing prices or to enable Townsend to fix or dictate the prices charged for the patented lockbolts." Huck granted only two other licenses, both of which were limited to the making and selling of lockbolts made of titanium which Huck and Townsend do not make, and neither of these licenses require price maintenance.[3]

District court proceedings

The Government filed a criminal indictment of Huck and Townsend in 1961, charging price fixing. At the close of the Government's case, the district court granted a motion for acquittal on the ground that the facts established did not constitute violations of Section 1 of the Sherman Act without evidence that what was obtained by defendants by their alleged agreements was more than a normal and reasonable reward to a patentee. The Government then proceeded to sue the defendants civilly using the record in the criminal case, by stipulation, as its evidence. .[4] The defendants denied the Government's charges of a combination and conspiracy in unreasonable restraint of trade and to monopolize interstate trade in lockbolts, but had not put in their evidence; on that record, the district court granted defendant's motions to dismiss the case.[5]

The waiver and mootness issues

At a civil pretrial conference, Government counsel allegedly stated that the Government is not attempting to have the doctrine of the General Electric case overruled and only maintains that the facts in this case do not fall within that doctrine—in other words, that the doctrine of the General Electric case is still good law but does not apply here because the defendants' actions in this case are illegal because they are outside the application of the doctrine—went beyond what was permissible under General Electric.

There was some disagreement about what actually had been said, counsel for the Government (Assistant Attorney General Turner) suggesting to the Court in oral argument that the so-called waiver came only from erroneous notes taken by the judge's law clerk. The Government argued in the Supreme Court that any failure of the Government to raise the issue at trial did not (1) make it unfair to the defendants to consider the issue on appeal, or (2) deprive the Court of any significant record material that would have materially assisted the Court in deciding the issues presented concerning the General Electric case. In hearing oral argument, the Chief Justice said (at least for him) this was an issue of whether the Government was misleading the Court.

Government counsel maintained that "the relevant factual and legal issues raised by the GE Rule are simply not issues on which any record would have provided this Court with any material help, and it is for that reason that I think it is appropriate now . . . to take a careful look at the merits because if we are right on this, we think the Court should take this opportunity to overrule the General Electric case." Any evidence concerning the GE rule, he said, would be speculative and thus "worthless." He also insisted that the underlying facts were kept secret and could not be ascertained.

Another troubling issue was that the patents had two years to run, so that it was unlikely that the final judgment could occur during the life of the patents. Some justices wondered whether it was worthwhile to decide the case in light of this factor.[6]

District court's view of merits

The district court determined "upon the evidence submitted that the case at bar is in all material respects the same as and ruled by the decision in United States v. General Electric Co. The Government urged that the case was controlled by United States v. Masonite Corp., United States v. Univis Lens Co., United States v. Line Material Co., United States v. United States Gypsum Co., United States v. New Wrinkle, Inc., Newburgh Moire Co. v. Superior Moire Co.,[7] United States v. Besser Mfg. Co.,;[8] United States v. Krasnov,[9] United States v. General Electric Co.[10] The district court disagreed. It said that the present case was distinguished from these cases "in substantially the same respects as the General Electric case: was, in that:

In the case at bar the Court finds no industry-wide price-fixing licensing, no agreement or conspiracy between a plurality of licensees preventing grant of other licenses by the patent owner, no granting of a plurality of price-fixing licenses to a plurality of competing licenses, no cross licensing by one patent owner creating by contract in another the power to issue licenses and fix prices under patents which are not owned by the licensor, no pooling of independently owned competing patents with price-fixing licenses under the pooled competing patents, no arrangements for control of resale prices of patented devices, and no agreements for fixing prices on unpatented articles—some or all of which practices were found to be controlling aspects of the situations in the cases above mentioned on which the Government relies.[11]

The district court therefore concluded:

- [U]upon the evidence submitted by the plaintiff, and the law applicable thereto, that the plaintiff has not shown by preponderance of evidence that the defendants have or are engaged in a combination and conspiracy in unreasonable restraint of trade and to monopolize interstate trade and commerce in lockbolts in violation of Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act, and has not shown any right to relief as prayed.

- [T]he plaintiff has failed to prove a violation of Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act for the additional reason that it failed to show that the patent arrangements between Huck and Townsend were designed [806] to or did secure a reward beyond that to which Huck as the patent owner was legally entitled.[12]

Proceedings in Supreme Court

The Government appealed to the Supreme Court, which affirmed without opinion because it was divided 4–4.

Commentary

● Richard W. McLaren, Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Antitrust Division, was quoted as saying:

[T]he rule of General Electric has been getting narrower all the time. As you know, the Supreme Court has twice split four to four on the issue of whether to overrule the General Electric case altogether. In the more recent effort, United States v. Huck Manufacturing Co., a procedural error in the lower court hampered the Government's position. We believe that, when the question is properly brought to the Supreme Court again, the Court will completely overrule the General Electric doctrine. Apparently our confidence is shared by members of the bar who 'have occasion to draw up patent licenses, since we seem to be having some difficulty in finding an appropriate case in which to present the question to the Supreme Court.[13]

See also

- Oral argument before Supreme Court in Huck case.

References

| The citations in this Article are written in Bluebook style. Please see the Talk page for this Article. |

- ↑ United States v. Huck Mfg. Co., 227 F. Supp. 791 (E.D. Mich. 1964). Justice Abe Fortas did not participate.

- ↑ 227 F. Supp. at 796-99.

- ↑ 227 F. Supp. at 799-800.

- ↑ 227 F. Supp. at 793.

- ↑ 227 F. Supp. at 794-95.

- ↑ Oral argument.

- ↑ 237 F.2d 283 (3d Cir. 1955).

- ↑ 96 F. Supp. 304, 310-311 (E.D. Mich. 1951).

- ↑ 143 F. Supp. 184 (E.D. Pa. 1952).

- ↑ 80 F. Supp. 989 (S.D.N.Y. 1948) (Carboloy case).

- ↑ 227 F. Supp. at 805.

- ↑ 227 Dentsply at 805-06.

- ↑ J. Patrick Kittler, Current State of Patent and Know-How Licensing, 27 Business Lawyer 691, 706 (1972).