United States presidential elections in which the winner lost the popular vote

There have been five United States presidential elections in which the winner lost the popular vote. In the United States presidential election system the nationwide popular vote does not determine the outcome of the election. Rather, the President of the United States is determined by votes cast by electors of the Electoral College, or, if no candidate receives an absolute majority of electoral votes, by the House of Representatives. These procedures are governed by the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

When individuals cast ballots in the general election, they are choosing electors and telling them who they should vote for in the electoral college. The "national popular vote" is the sum of all the votes cast in the general election, nationwide. The presidential elections of 1876, 1888, and 2000 produced an Electoral College winner who did not receive at least a plurality of the popular vote.[1] This will apparently happen again in the 2016 election.[2][3] In 1824, there were six states in which electors were legislatively appointed, rather than popularly elected, so the true national popular vote is uncertain. When no candidate received a majority of electoral votes in 1824, the election was decided by the House of Representatives and so could be considered distinct from the latter four elections in which all of the states had popular selection of electors.[4] The true national popular vote total was also uncertain in the 1960 election, and the plurality for the winner depends on how votes for Alabama electors are allocated.[5]

Elections

1824: John Quincy Adams

In the 1824 presidential election John Quincy Adams was elected President on February 9, 1825. The election was decided by the House of Representatives under the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution after no candidate secured the required number of votes from the Electoral College. All four candidates in the election identified with the Democratic-Republican Party. Andrew Jackson had received the most votes (a plurality), but not the required majority of electoral votes necessary to avoid sending the election to the House. This became a source of great bitterness for Jackson and his supporters, who proclaimed the election of Adams a "corrupt bargain" and were inspired to create the Democratic Party.[6][7]

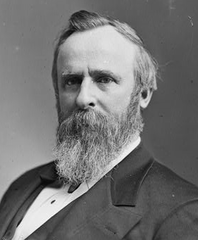

1876: Rutherford B. Hayes

The 1876 presidential election was one of the most contentious and controversial presidential elections in American history. The results of the election remain among the most disputed ever, although there is no question that Democrat Samuel J. Tilden of New York outpolled Ohio's Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in the popular vote, with Tilden winning 4,288,546 votes and Hayes winning 4,034,311. After a first count of votes, Tilden won 184 electoral votes to Hayes' 165, with 20 votes unresolved. These 20 electoral votes were in dispute in four states: in the case of Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, each party reported its candidate had won the state, while in Oregon one elector was declared illegal (as an "elected or appointed official") and replaced. The question of who should have been awarded these electoral votes is the source of the continued controversy concerning the results of this election.

An informal deal was struck to resolve the dispute: the Compromise of 1877, which awarded all 20 electoral votes to Hayes. In return for the Democrats' acquiescence in Hayes' election, the Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South, ending Reconstruction. The Compromise effectively ceded power in the Southern states to the Democratic Redeemers, who went on to pursue their agenda of returning the South to a political economy resembling that of its pre-war condition, including the disenfranchisement of black voters.[8][9]

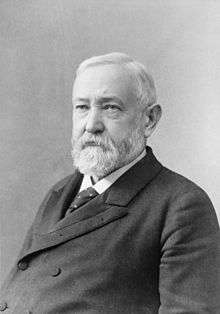

1888: Benjamin Harrison

In the 1888 contest Grover Cleveland of New York, the incumbent president and a Democrat, tried to secure a second term against the Republican nominee Benjamin Harrison, a former U.S. Senator from Indiana. The economy was prosperous and the nation was at peace, but Cleveland lost re-election in the Electoral College, even though he won a plurality of the popular vote by a narrow margin.

Tariff policy was the principal issue in the election. Harrison took the side of industrialists and factory workers who wanted to keep tariffs high, while Cleveland strenuously denounced high tariffs as unfair to consumers. His opposition to Civil War pensions and inflated currency also made enemies among veterans and farmers. On the other hand, he held a strong hand in the South and border states, and appealed to former Republican Mugwumps.

Harrison swept almost the entire North and Midwest (losing only Connecticut and New Jersey), and narrowly carried the swing states of New York (Cleveland's home state) and Indiana (Harrison's home state) by a margin of 1% or less to achieve a majority of the electoral vote. Unlike the election of 1884, the power of the Tammany Hall political machine in New York City helped deny Cleveland the electoral votes of his home state.[10][11]

2000: George W. Bush

The 2000 presidential election pitted Republican candidate George W. Bush (the incumbent governor of Texas and son of former president George H. W. Bush) against Democratic candidate Al Gore (the incumbent Vice President of the United States). Despite Gore receiving 543,895 more votes (0.51% of all votes cast), the Electoral College chose Bush as president.[12]

Vice President Gore secured the Democratic nomination with relative ease. Bush was seen as the early favorite for the Republican nomination, and despite a contentious primary battle with Senator John McCain and other candidates, secured the nomination by Super Tuesday. Many third-party candidates also ran, most prominently Ralph Nader. Bush chose former Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney as his running mate, and Gore chose Senator Joe Lieberman as his. Both major-party candidates focused primarily on domestic issues, such as the budget, tax relief, and reforms for federal social-insurance programs, though foreign policy was not ignored.[13]

The result of the election hinged on voting in Florida, where Bush's narrow margin of victory of just 534 votes out of almost 6 million votes cast on election night triggered a mandatory recount. Litigation in select counties started additional recounts, and this litigation ultimately reached the United States Supreme Court. The Court's contentious decision in Bush v. Gore, announced on December 12, 2000, ended the recounts, effectively awarding Florida's votes to Bush and granting him the victory. Later studies have reached conflicting opinions on who would have won the recount had it been allowed to proceed.[14] Nationwide, George Bush received 50,456,002 votes (47.87%) and Gore received 50,999,897 (48.38%).[12]

2016: Donald Trump

When the United States Electoral College casts their electoral votes in December 2016,[15] it will most likely elect Donald Trump as president, pursuant to the popular vote in each electors' respective state. On that basis, Trump is expected to receive more than the required 270 electoral college votes required to become president. As of December 2, 2016, Hillary Clinton had nonetheless received 2.6 million more votes in the general election than Trump, giving Clinton a 1.91% popular vote lead over Trump.[16]

One scenario in which Trump might not become president involves the electoral college. As originally set up, the electoral college was intended to debate and vote on the candidates; the general election merely decided who the electors would be. As of November 2016, 29 states and the District of Columbia legally require their electors to vote according to the popular vote in their state, but other states still allow their electors to vote against their state's popular vote (earning such electors the label "faithless electors"). A scenario where Clinton wins is not impossible[17] but is very unlikely because about 37 Republican electors would have to vote against their party's candidate and their respective state's plurality vote.[18] Various petitions are being circulated asking the electoral college to elect Clinton instead of Trump. As of November 12, 2016, according to FoxNews, one of these petitions had garnered over 3 million signatures.[17]

Comparative table of elections

| Democratic-Republican · DR Democratic · D Republican · R | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election | Winner and party | Electoral College | Popular vote[lower-alpha 1] | Runner-up and party | Turnout[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||

| Votes | % | Votes | Margin | % | Margin | % | |||||||

| 1824 | John Quincy Adams | DR | 84/261 | 32.18% | 113,122 | −38,149 | 30.92% | −10.44% | Andrew Jackson | DR | 26.90% | ||

| 1876 | Rutherford Hayes | R | 185/369 | 50.14% | 4,034,142 | −252,666 | 47.92% | −3.00% | Samuel Tilden | D | 81.80% | ||

| 1888 | Benjamin Harrison | R | 233/401 | 58.10% | 5,443,633 | −94,530 | 47.80% | −0.83% | Grover Cleveland | D | 79.30% | ||

| 2000 | George W. Bush | R | 271/538 | 50.37% | 50,460,110 | −543,816 | 47.87% | −0.51% | Al Gore | D | 51.30% | ||

| 2016 | Donald Trump | R | 306/538[lower-alpha 2] | 56.88%[lower-alpha 2] | 62,625,786[lower-alpha 3] | −2,504,788[lower-alpha 3] | 46.17%[lower-alpha 3] | −1.85%[lower-alpha 3] | Hillary Clinton | D | TBD | ||

Notes

- 1 2 Popular vote and voter turnout figures for the 1824 election exclude Delaware, Georgia, Louisiana, New York, South Carolina, and Vermont. In all of these states, the electors were chosen by the state legislatures rather than by popular vote.[19]

- 1 2 Electoral vote figures are only projected. The Electoral College will vote on December 19, 2016. Then, on January 6, 2017, the Congress will meet in joint session to count the electoral votes and declare who has been elected President.[20]

- 1 2 3 4 Votes from the 2016 presidential election are still being counted; these are the latest verified figures.[21][22] Additionally, a recount is pleaded for in some states.[23]

1960 Alabama results ambiguity

In the 1960 United States presidential election, Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy defeated Republican candidate Richard Nixon. Kennedy is generally considered to have won the popular vote as well, by a narrow margin, but based on the unusual nature of the election in Alabama, political journalists John Fund and Sean Trende have argued that Nixon actually won the popular vote.[24][25][26]

See also

- List of United States presidential elections by Electoral College margin

- List of United States presidential elections by popular vote margin

- Contemporary issues and criticism of the Electoral College

- National Popular Vote Interstate Compact

References

- ↑ Edwards III, George C. (2011). Why the Electoral College is Bad for America (Second ed.). New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16649-1.

- ↑ Chang, Alvin (November 9, 2016). "Trump will be the 4th president to win the Electoral College after getting fewer votes than his opponent". Vox. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ↑ "2016 Presidential Election". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- ↑ "Electoral College Mischief, The Wall Street Journal, September 8, 2004". Opinionjournal.com. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Did JFK Lose the Popular Vote?". RealClearPolitics. October 22, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ↑ "The Election of 1824 Was Decided in the House of Representatives: The Controversial Election was Denounced as 'The Corrupt Bargain'", Robert McNamara, About.com

- ↑ Stenberg, R. R. (1934). "Jackson, Buchanan, and the "Corrupt Bargain" Calumny". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 58 (1): 61–85. doi:10.2307/20086857.

- ↑ Jones, Stephen A.; Freedman, Eric (2011). Presidents and Black America. CQ Press. p. 218. ISBN 9781608710089.

In an eleventh-hour compromise between party leaders - considered the "Great Betrayal" by many blacks and southern Republicans ...

- ↑ Downs, 2012

- ↑ Calhoun, page 43

- ↑ Socolofsky & Spetter, page 13

- 1 2 2000 Presidential Electoral and Popular Vote Summary, Federal Election Commission

- ↑ "Once Close to Clinton, Gore Keeps a Distance". The New York Times. 20 October 2000. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ CNN, Wade Payson-Denney. "Who really won Bush-Gore election?". cnn.com. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ "Electoral College Timeline of Key Dates" (PDF). National Archives and Records Administration’s Office of the Federal Register.

- ↑ David Wasserman. "2016 National Popular Vote Tracker". The Cooke Political Report. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- 1 2 "Voters target Electoral College members to switch their Trump ballots, elect Clinton".

- ↑ Cheney, Kyle. "Democratic presidential electors revolt against Trump". Politico.

- ↑ Leip, David. "1824 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 26, 2005.

- ↑ "U.S. Electoral College: The 2016 Presidential Election". National Archives and Records Administration. 2016. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ↑ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- ↑ "SOS - 2016 Presidential Election Results". www.michigan.gov. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- ↑ "The US election recount is a long shot – but the alternative is catastrophe". The Guardian. 2016-11-29. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- ↑ Trende, Sean (October 19, 2012). "Did JFK Lose the Popular Vote?".

- ↑ Azari, Julia (November 10, 2016). "Most People Hate The Electoral College, But It's Not Going Away Soon".

- ↑ Fund, John (November 20, 2003). "A Minority President". Opinion Journal. Archived from the original on November 23, 2003. Retrieved 25 August 2016.