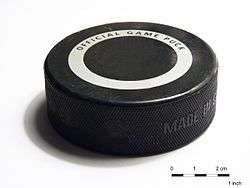

Hockey puck

A hockey puck is a disk made of vulcanized rubber that serves the same functions in various games as a ball does in ball games. The best-known use of pucks is in ice hockey, a major international sport.

Origins

Many tribes throughout North America played a version of field hockey which involved some type of "puck" or ball, and curved wooden sticks. Ice hockey was first observed by Europeans being played by Mi'kmaq Indians in Nova Scotia in the late 17th century. It was called ricket by the Natives. The game was played utilizing a frozen road apple as the first puck. Eventually, they began to carve pucks from cherrywood, which was the puck of preference until late in the century when rubber imported by Euro-Americans replaced the wood.[1]

Etymology

The origin of the word puck is obscure. The Oxford English Dictionary suggests the name is related to the verb to puck (a cognate of poke) used in the game of hurling for striking or pushing the ball, from the Scottish Gaelic puc or the Irish poc, meaning "to poke, punch or deliver a blow":[2][3]

It is possible that Halifax natives, many of whom were Irish and played hurling, may have introduced the word to Canada. The first known printed reference was in Montreal, in 1876 (Montreal Gazette of February 7, 1876), just a year after the first indoor game was played there.

A hockey puck is also referred to colloquially as a biscuit. To put the "biscuit" in the "basket" (colloquial for the goal/net) is to score a goal.

In ice hockey

Ice hockey requires a hard disk of vulcanized rubber. A standard ice hockey puck is black, 1 inch (25 mm) thick, 3 inches (76 mm) in diameter, and weighs between 5.5 and 6 ounces (156 and 170 g);[4] some pucks are heavier or lighter than standard (see below). Pucks are often marked with silkscreened team or league logos on one or both faces.[4] Pucks are frozen before the game to reduce bouncing during play.[4]

Ice hockey and its various precursor games utilized balls until the late 19th century. By the 1870s, 'flat' pucks were made of wood as well as rubber. At first, pucks were square. The first recorded organized game of ice hockey used a wooden puck to prevent it from leaving the rink of play.[5] The rubber pucks were first made by slicing a rubber ball, then trimming the disc square. The Victoria Hockey Club of Montreal is credited with making and using the first round pucks in the 1880s.[6]

Variations

There are several variations on the standard black, 6 ounces (170 g) hockey puck. One of the most common is a blue, 4 ounces (110 g) puck that is used for training younger players who are not yet able to use a standard puck. Heavier 10 ounces (280 g) training pucks, typically reddish pink or reddish orange in colour, are also available for players looking to develop the strength of their shots or improve their stick handling skills. Players looking to increase wrist strength often practice with steel pucks that weigh 2 pounds (910 g); these pucks are not used for shooting, as they could seriously harm other players. White pucks can be used for goalie training. These are regulation size and weight, but made from white rubber. A hollow, light-weight fluorescent orange puck is available for road or floor hockey. Other variants, some with plastic ball bearings or glides, are available for use for road or roller hockey.

The FoxTrax "smart puck" was developed by the Fox television network when it held NHL broadcasting rights for the U.S. The puck had integrated electronics to track its position on screen; a blue streak traced the path of the puck across the ice. The streak would turn red if the puck was shot especially hard. This was an experiment in broadcasting intended to help viewers unfamiliar with hockey to better follow the game by making the puck more visible. It was ill-received by many traditional hockey fans, but appreciated by many of the more casual viewers. The system debuted with much publicity in the All Star game at the Boston Fleet Center on January 20, 1996, but the system was shelved when Fox Sports lost the NHL broadcast rights three years later.

Firepuck

The use of the Firepuck in the early 1990s was the first attempt to improve the visibility of hockey pucks as seen on television. This invention incorporated coloured retro reflective materials of either embedded lens elements or prismatic reflectors laminated into recesses on the flat surfaces and the vertical edge of a standard hockey puck. Yellow was the preferred reflected colour. A spotlight was required to be positioned on the TV camera and focused at the centre of the viewing area.

A short demonstration tape of the Minnesota North Stars skating with the Firepuck was shown during the period break at the 1993 National Hockey League All Star game in Montreal, Canada. The International Hockey League (IHL) pursued testing the Firepuck with its inventor, Donald Klassen. The next television viewing was the IHL All star game in Fort Wayne IN, January 1994, where the Firepuck was used the entire game. The IHL tested the Firepuck in two more games, and finally the East Coast Hockey League used it January 17, 1997, for their All Star game.

The use of the Firepuck was discontinued because of these reasons:

- The slight structural change increased the tendency for the puck to bounce on the ice. This made it more difficult for the goaltender and resulted in increased scoring.

- The skaters objected to the use of camera spotlights which reflected off the ice.

- The television viewing contrast of the Firepuck was not noticeably enhanced when the camera view was of the entire rink, this being the most common camera shot.

The Firepuck name was branded during the 90s but has since been discontinued.

In game play

During a game, pucks can reach speeds of 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) or more when struck. Zdeno Chára, whose slapshot clocked 108.8 miles per hour (175.1 km/h) in the 2013 NHL All Star Game SuperSkills competition, broke his own earlier record.[7] The current world record is held by Denis Kulyash of KHL's Avangard Omsk, who slapped a puck at the 2011 KHL All Star Game skills competition in Riga, Latvia with a speed of 110 miles per hour (180 km/h).[8]

Fast-flying pucks are potentially dangerous to players and spectators. Puck-related injuries at hockey games are not uncommon. This led to the evolution of various types of protective gear for players, most notably the goaltender mask. The most serious incident involving a spectator took place on March 18, 2002, when a thirteen-year-old girl, Brittanie Cecil, died two days after being struck on the head by a hockey puck deflected into the crowd at a National Hockey League game between the Calgary Flames and Columbus Blue Jackets in Columbus. This is the only known incident of this type to have occurred in the history of the league. Partly as a result of this event, the glass or plexiglass panels that sit atop the boards of hockey rinks to protect spectators have been supplemented with mesh nets that extend above the upper edge of the glass.

Manufacture

NHL regulation pucks were not required for professional play until the 1990–91 season, but were standardized for consistent play and ease of manufacture half a century earlier, by Art Ross, in 1940.[4] Major manufacturers of pucks exist in Canada, Russia, the Czech Republic, the People's Republic of China,[4] and Slovakia.[9]

The list of former or present-day major producers includes

-

Viceroy

Viceroy -

Sher-Wood

Sher-Wood -

Gufex[10]

Gufex[10] -

Rubena[10]

Rubena[10] -

Vegum Dolné Vestenice[11]

Vegum Dolné Vestenice[11] -

Converse

Converse -

HockeyShot

HockeyShot -

Spalding

Spalding -

Xiamen Yin Hua Silicone Rubber Products Co., Ltd.

Xiamen Yin Hua Silicone Rubber Products Co., Ltd. -

Xiamen Deng Hong Silica Gel Product Co., Ltd.

Xiamen Deng Hong Silica Gel Product Co., Ltd. -

Xiamen Ijetech Industry & Trade Co. Ltd

Xiamen Ijetech Industry & Trade Co. Ltd

The black rubber of the puck is made up of a mix of natural rubber, antioxidants, bonding materials and other chemicals to achieve a balance of hardness and resilience.[12] This mixture is then turned in a machine with metal rollers, where workers add extra natural rubber, and ensure that the mixing is even. Samples are then put into a machine that analyzes if the rubber will harden at the right temperature. An automated apparatus, called a pultrusion machine,[4] extrudes the rubber into long circular logs that are 3 inches (7.6 cm) in diameter and then cut into 1 inch (2.5 cm) thick pieces while still soft. These pre-forms are then manually put into moulds that are the exact size of a finished puck.[12] There are up to 200 mould cavities per moulding palette, capable of producing up to 5,000 pucks per week.[4] The moulds are then compressed. This compression may be done cold[4] or with the moulds heated to 300 °F (149 °C) for 18 minutes,[12] depending on the proprietary methods of the manufacturer. They come out hard and then are allowed to sit for 24 hours. Each puck is manually cleaned with a trimmer machine to remove excess rubber. The molding process adds a diamond cross-hatch texture around the edge of the puck for more friction between the stick and puck for better control and puck handling.[12]

The practice pucks are made by a similar but faster process that uses larger pre-forms, 4–5 in (10–13 cm) thick, puts them into molds automatically, and applies more pressure and heat over a shorter period of time to compress the puck into the standard size. This allows approximately twice as many pucks to be manufactured in the same time period as the more exacting production of NHL regulation pucks. People sometimes freeze pucks to prevent them from sticking to the ice.[4]

In roller hockey

Roller hockey pucks are similar to ice hockey pucks, but made from plastic and thus lighter. They have small ribs protruding from their tops and bottoms which limit contact with the surface, allowing better sliding motion and less friction.

Most commonly red, roller hockey pucks can be found in almost any colour, although light, visible colours such as red, orange, yellow, pink, and green are typical.

Roller hockey pucks were created so inline hockey and street hockey players could play with a puck instead of a ball on surfaces such as hardwood, concrete, and asphalt.

In underwater hockey

An underwater hockey puck (originally but now rarely referred to as a "squid" in the United Kingdom), while similar in appearance to an ice hockey puck, differs in that it has a lead core weighing approximately 3 pounds (1.4 kg) within a teflon, plastic or rubber coating. This makes the puck dense enough to sink in a swimming pool, though it can be lofted during passes, while affording some protection to the pool tiles.

A smaller and lighter version of the standard puck exists for junior competition and is approximately 1 lb 12 oz (0.80–0.85 kg) and of similar construction to the standard puck.

While there are numerous regional variations in colour, construction and materials all must conform to international regulations stipulating overall dimensions and weight. The regulations state that pucks should be a bright distinctive colour, for example high-visibility pink or orange, and that for World Championships these are the only acceptable colours.

In other sports and games

The term "puck" is sometimes also applied to similar (though often smaller) gaming discs in other sports and games, including novuss, shuffleboard, table shuffleboard, box hockey and air hockey.

Alternative uses

Ice hockey pucks of regulation 3 inch diameter and 1 inch thickness may be used as mechanical vibration dampening isolators in places such as feet for light industrial air compressors, and air conditioning units because they are of regulation materials and therefore consistent manufacture, size and shape, and are constructed of a repeatable and consistent vulcanized rubber material. Since the material is rubber, it may be drilled out or milled easily to a fixed depth as rubber feet or used as rubber spacer or gasket material. A very common use of a slotted hockey puck is as an adaptor between the metal foot of a trolley jack and the sill (rocker panel) of an automobile. The sill has a spot-welded lip which fits into the slot of the puck and would otherwise be bent or marked by the metal foot. Hockey pucks have been used to level furniture, beverage refrigeration systems, and as paper weights or door stops. The hockey puck has many uses other than its original, intended purpose by virtue of its consistent physical properties.

See also

References

- ↑ "History of Native Hockey". Nativehockey.com.

- ↑ Beauchamp, J. Clem (September 1943). Montreal Star. Missing or empty

|title=(help), citing Joyce 1910. - ↑ Joyce, P.W. (1910). English as We Speak It in Ireland.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Hockey Puck: How Products are Made". eNotes. Archived from the original on April 4, 2011. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ McKinley 2006, p. 9.

- ↑ "McGill Man Tells of How First Rules for Hockey Were Written". Montreal Gazette. December 17, 1936. p. 17.

- ↑ "Chara breaks own Hardest Shot record, hits 105.9 mph". Yahoo! Sports Puck Daddy. 2011-01-29. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- ↑ "World record for fastest slap shot beaten at KHL All-Star game". RT. 2011-02-06. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- ↑ VESTENICE, DOLNE, "HOCKEY PUCKS FROM VEGUM", Slovak Heritage Live newsletter, Volume 6, No. 3, Fall 1998

- 1 2 Olympijské góly v Soči obstarají puky z Náchoda. Překvapený je i výrobce

- ↑ Na MS sa bude hrať s českými pukmi, slovenské v NHL, hockeyslovakia.sk (Slovak)

- 1 2 3 4 "How it's made: Hockey Pucks". ScienceHack. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- McKinley, Michael (2006). Hockey: A People's History. Toronto, Ontario: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 0-7710-5769-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ice hockey pucks. |