U Dhammaloka

| Dhammaloka | |

|---|---|

| ဦးဓမ္မလောက | |

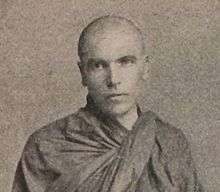

Dhammaloka in 1902 aged about 50. | |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Theravada |

| Dharma names | Dhammaloka |

| Personal | |

| Born |

Laurence Carroll Laurence O'Rourke William Colvin 1856 Dublin (?), Ireland |

| Died |

1914 (aged 58) Unknown |

U Dhammaloka (Burmese: ဦးဓမ္မလောက; c. 1856 – c. 1914) was an Irish-born migrant worker [1] turned Buddhist monk, atheist critic of Christian missionaries, and temperance campaigner who took an active role in the Asian Buddhist revival around the turn of the twentieth century.

Dhammaloka was ordained in Burma prior to 1900, making him one of the earliest attested western Buddhist monks. He was a celebrity preacher, vigorous polemicist and prolific editor in Burma and Singapore between 1900 and his conviction for sedition and appeal in 1910–1911. Drawing on western atheist writings, he publicly challenged the role of Christian missionaries and by implication the British empire.

Early life

Dhammaloka's early life and given name are as yet uncertain. He reportedly gave at least three names for himself – Laurence Carroll, Laurence O'Rourke and William Colvin. On occasion he used the nom de plume "Captain Daylight". It is accepted that he was Irish, almost certainly born in Dublin in the 1850s, and emigrated to the United States, possibly via Liverpool. He then worked his way across the US as a migrant worker before finding work on a trans-Pacific liner. Leaving the ship in Japan, he made his way to Rangoon, arriving probably in the late 1870s or early 1880s, before the final conquest of Upper Burma by the British.[2][3][4][5]

Burmese career

In Burma, he found work in Rangoon as a tally clerk in a logging firm[6] before becoming interested in the Burmese Buddhism he saw practised all around him. Around 1884, he took ordination as a novice monk under the name Dhammaloka.[7] Fully ordained sometime prior to 1899, he began work as a teacher (probably in the Tavoy monastery in Rangoon). By 1900, he had gained the status of a senior monk in that monastery[8] and began travelling and preaching throughout Burma,[9][2][5] becoming known as the "Irish pongyi" or "Irish Buddhist".

In 1900, Dhammaloka began his public career with two largely unnoticed advertisements forbidding Christian missionaries to distribute tracts[10] and a more dramatic – and widely reprinted – declaration, first published in Akyab, warning Buddhists of the threats Christian missionaries posed to their religion and culture.[11] Following a 1901 preaching tour, he confronted an off-duty British Indian police officer at the Shwedagon pagoda in Rangoon in 1902 over the wearing of shoes – a contentious issue in Burma as Burmese Buddhists would not wear shoes on pagoda grounds. The Indians who staffed the police force equally went barefoot in Indian religious buildings, but off-duty visited Burmese pagodas in boots, in what was interpreted as a mark of serious disrespect. Attempts by the officer and the British authorities to bring sedition charges against Dhammaloka and to get pagoda authorities to repudiate him failed, boosting his public reputation.[12] Later that year he held another preaching tour, which drew huge crowds.[13]

After some years' absence Dhammaloka returned to Burma in 1907,[14] establishing the Buddhist Tract Society (see below). In December a reception in his honour was held in Mandalay with hundreds of monks and he met the new Thathanabaing, the government recognised head of the sangha;[15] in early 1908 he held another preaching tour, and continued preaching until at least 1910[16] and his trial for sedition (see below).

Other Asian projects and travels

Singapore

Outside of Burma, Dhammaloka's main base was Singapore and other Straits Settlements (Penang, Kuala Lumpur, Ipoh). In Singapore, he stayed initially with a Japanese Buddhist missionary Rev. Ocha before establishing his own mission and free school on Havelock Road in 1903, supported mainly by the Chinese community and a prominent local Sri Lankan jeweller. By 1904 he was sending Europeans to Rangoon for ordination (April) and holding a public novice ordination of the Englishman M. T. de la Courneuve (October). In 1905 the editor of the previously sympathetic Straits Times, Edward Alexander Morphy (originally from Killarney, Ireland), denounced him in the paper as a 'fraud'.[17]

Japan

Dhammaloka unexpectedly left Burma in 1902, probably hoping to attend the 'World's Parliament of Religions' rumoured to be taking place in Japan. Though no Parliament took place, Japanese sources attest that in September 1902 Dhammaloka attended the launch of the International Young Men's Buddhist Association (IYMBA, Bankoku bukkyō seinen rengōkai) at Takanawa Buddhist University, Tokyo. He was the only non-Japanese speaker among a group of prominent Jōdo Shinshū Buddhist clerics and intellectuals including Shimaji Mokurai. Dhammaloka's presence at an October 'student conference' at the same university in company with the elderly Irish-Australian Theosophist Letitia Jephson is also described by American author Gertrude Adams Fisher in her 1906 travel book A Woman Alone in the Heart of Japan.[18]

Siam

From February to September 1903 Dhammaloka was based at Wat Bantawai in Bangkok, where he founded a free multiracial English-language school, promoted Buddhist associations and proposed an IYMBA-style world congress of Buddhists. He was again reported in Siam in 1914 and may have died there.[19]

Other locations

Dhammaloka is also recorded as having significant links in China and Ceylon (in both of which he published tracts.)[20][21] There are plausible newspaper reports of his visits to Nepal in 1905[22][23] and Australia (1912) and Cambodia (1913). Dhammaloka's claim to have travelled to Tibet well before Younghusband's expedition of 1904, though reported as far afield as Atlanta and Dublin, remains unconfirmed.[24]

Publications

Dhammaloka produced a large amount of published material, some of which, as was common for the day, consisted of reprints or edited versions of writing by other authors, mostly western atheists or freethinkers, some of whom returned the favour in kind.[25] In the early 1900s Dhammaloka published and reprinted a number of individual tracts attacking Christian missionaries or outlining Buddhist ideas.

In 1907 he founded the Buddhist Tract Society in Rangoon, which produced a large number of tracts of this nature. It was originally intended to produce ten thousand copies of each of a hundred tracts; while it is not clear if it reached this number of titles, print runs were very large.[26] To date copies or indications have been found of at least nine different titles, including Thomas Paine's Rights of Man and Age of Reason, Sophia Egoroff's Buddhism: the highest religion, George W Brown’s The teachings of Jesus not adapted to modern civilisation, William E Coleman’s The Bible God disproved by nature, and a summary of Robert Blatchford.[27]

Beyond this, Dhammaloka was an active newspaper correspondent, producing a large number of reports of his own activities for journals in Burma and Singapore (sometimes pseudonymously; Turner 2010: 155)[28] and exchanging letters with atheist journals in America and Britain.[29] He was also a frequent topic of comment by the local press in South and Southeast Asia, by missionary and atheist authors, and by travel writers such as Harry Franck (1910).[30]

Controversy

Dhammaloka's position was inherently controversial.[31][32] As a Buddhist preacher he seems to have deferred to Burmese monks for their superior knowledge of Buddhism and instead spoken primarily of the threat of missionaries, whom he identified as coming with "a bottle of 'Guiding Star brandy', a 'Holy bible' or 'Gatling gun'," linking alcoholism, Christianity and British military power.[33]

Unsurprisingly responses to Dhammaloka were divided. In Burma he received support from traditionalists (he was granted a meeting with the Thathanabaing, was treated with respect among senior Burmese monks and a dinner was sponsored in his honour), from rural Burmese (who attended his preaching in large numbers, sometimes travelling several days to hear him; in at least one case women laid down their hair for him to walk on as a gesture of great respect) and from urban nationalists (who organised his preaching tours, defended him in court etc.; Turner 2010). Anecdotal evidence also indicates his broader popularity in neighbouring countries.[30] While also popular in Singapore, particularly among the Chinese community, Bocking's research has shown that he was less successful in Japan and in Siam.[34]

Conversely much European opinion was hostile, including naturally that of missionaries and the authorities, but also some journalists (although others did appreciate him and printed his articles as written). In general he was accused of hostility to Christianity, of not being a gentleman or well-educated, and of stirring up "the natives."[32][35]

Trial and disappearance

Dhammaloka faced at least two encounters with the colonial legal system in Burma, in one and probably both of which he received minor convictions. Turner[36][37] speculates that this was to avoid the potential political embarrassment to the colonial authorities of trials with more substantial charges and hence a greater burden of proof.

During the shoe affair in 1902 it was alleged that Dhammaloka had said "we [the West] had first of all taken Burma from the Burmans and now we desired to trample on their religion" – an inflammatory statement taken as hostile to the colonial state and to assumptions of European social superiority. Following a failed attempt by the government to gather sufficient witnesses for a charge of sedition, a lesser charge of insult was made and it appears that Dhammaloka was summarily convicted on a charge of insult although the sentence is not known.[38]

In October and November 1910, Dhammaloka preached in Moulmein, leading to new charges of sedition laid at the instigation of local missionaries. Witnesses testified that he had described missionaries as carrying the Bible, whiskey and weapons, and accused Christians of being immoral, violent and set on the destruction of Burmese tradition. Rather than a full sedition charge, the crown opted to prosecute through a lesser aspect of the law (section 108b) geared to the prevention of future seditious speech, which required a lower burden of proof and entailed a summary hearing. He was bound over to keep the peace and ordered to find two supporters to guarantee this with a bond of 1000 rupees each.[39]

This trial was significant for a number of reasons. It was one of the few times the sedition law (designed to prevent native Indian and Burmese journalists from criticising the authorities) was used against a European, the first time it was applied in Burma and precedent-setting for its use against nationalists.[37] On appeal, he was defended by the leading Burmese nationalist U Chit Hlaing, future president of the Young Men's Buddhist Association. The judge in the appeal, who upheld the original conviction, was Mr Justice Daniel H. R. Twomey (knighted in 1917), who wrote the definitive text on dovetailing Buddhist canon law and British colonial law and is of interest to scholars of religion as the grandfather of anthropologist Mary Douglas.[40]

Following the failure of his appeal, Dhammaloka's activities become harder to trace. In April 1912, a letter appeared in The Times of Ceylon. Reprinted in Calcutta and Bangkok, the letter purported to report his death in a temperance hotel in Melbourne, Australia. In June of the same year, however, he appeared in the offices of the Singapore Free Press to deny the report, whose motivation remains unclear.[41]

Between 1912 and 1913 Dhammaloka is known to have travelled in Australia (reportedly attending the 1912 annual Easter meeting of the I.O.G.T. temperance organisation in Brisbane), the Straits Settlements, Siam and Cambodia; in 1914 a missionary reported him alive in Bangkok running the "Siam Buddhist Freethought Association".[42][24] Although, to date, no reliable record of his death has been found, it would not necessarily have been reported during the First World War, if it had taken place while travelling, or indeed if he had been given a traditional monastic funeral in a country such as Siam or Cambodia.[24]

Influence and assessment

Dhammaloka has been largely forgotten by subsequent Buddhist history, with the exception of brief asides based on a 1904 newspaper item.[43][44]

On the western side, most accounts of early western Buddhists derive ultimately from Ananda Metteyya's followers, whose Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland was key to the formation of early British Buddhism.[45] These accounts do not mention Dhammaloka,[46] but construct a genealogy starting with Bhikkhus Asoka (H. Gordon Douglas), Ananda Metteyya (Allan Bennett) and Nyanatiloka (Anton Gueth).[47] By contrast with Dhammaloka, Ananda Metteyya was oriented toward the image of gentleman scholar, avoided conflict with Christianity and aimed at making western converts rather than supporting Burmese and other Asian Buddhists.[48] Dhammaloka's pugnacious Buddhist revivalism and intensive Asian Buddhist networking, by contrast, places him more beside figures such as Henry Steel Olcott and Anagarika Dharmapala. On the Burmese side, Dhammaloka takes up an intermediate place between traditionalist orientations towards simple restoration of the monarchy and the more straightforward nationalism of the later independence movement. His non-Burmese origins are inconvenient for later nationalist orthodoxy.[49]

Dhammaloka's identification of Buddhism with free thought – and his consequent rejection of multi-faith positions – was tenable within Theravada Buddhism. In terms of the global Buddhism of his day it aligned him with Buddhist rationalists[50] and those who aimed at a Buddhist revival resisting colonial and missionary Christianity; this contrasted both with post-Theosophist Buddhists who saw all religions as ultimately one[50] and with those who sought recognition for Buddhism as a world religion on a par with (and by implication extending equal recognition to) Christianity.[49]

Beyond this, his Buddhism seems to have focussed primarily on the major concerns for Burmese monks of the day, above all correct observance of the Vinaya.[7][51] In western terms this reflected a persistent concern of plebeian freethinkers in particular to assert that morality without threat of religious punishment was entirely possible, and to his own temperance concerns.

In Irish history, Dhammaloka stands out as a figure who rejected both Catholic and Protestant orthodoxies. Although not the only early Irish Buddhist[52] or atheist, he is also striking among these as being of plebeian and Catholic origin, undermining popular accounts which see the Republic of Ireland in particular as until recently homogenously Catholic. [53] Like other early Irish Buddhists, he appears as having "gone native" in Buddhist Asia, representing an anti-colonial solidarity marked by work within Asian Buddhist organisations and a hostility to Christian missionaries and imperialism. [54]

Notes

- ↑ O'Connell, Brian (5 July 2011). "Putting Faith in a Broader Vision of Religion". The Irish Times.

- 1 2 Turner, Cox & Bocking 2010, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Tweed 2010, p. 283.

- ↑ Cox 2009, pp. 135–6.

- 1 2 Cox 2010b, p. 215.

- ↑ Cox 2009, p. 135.

- 1 2 Skilton & Crosby 2010, p. 122.

- ↑ Turner 2010, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Turner 2010, pp. 151–152.

- ↑ Turner 2010, p. 151.

- ↑ Cox 2010b, p. 214.

- ↑ Turner 2010, pp. 154–155.

- ↑ Turner 2010, pp. 156–158.

- ↑ Turner 2010, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Turner 2010, p. 159.

- ↑ Turner 2010, p. 160.

- ↑ Bocking 2010a, pp. 255–266.

- ↑ Bocking 2010a, pp. 238–245.

- ↑ Bocking 2010a, pp. 246–254.

- ↑ Cox 2010b, pp. 178–9.

- ↑ Cox 2010b, p. 180.

- ↑ Turner, Cox & Bocking 2010, p. 127.

- ↑ Cox 2010b, p. 216.

- 1 2 3 Bocking 2011.

- ↑ Cox 2010b.

- ↑ Cox 2010b, pp. 180–182.

- ↑ Cox 2010b, pp. 194–200.

- ↑ Bocking 2010a, pp. 252–253.

- ↑ Cox 2010b, pp. 193–194.

- 1 2 Franck 1910.

- ↑ Turner 2009.

- 1 2 Turner 2010, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Cox 2010b, p. 192.

- ↑ Bocking 2010a.

- ↑ Cox 2010b, pp. 213–214.

- ↑ Turner 2010, p. 155.

- 1 2 Turner 2010, p. 161.

- ↑ Turner 2010, p. 154-155.

- ↑ Turner 2010, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Bocking 2010b.

- ↑ Turner, Cox & Bocking 2010, p. 141.

- ↑ Bocking 2010a, p. 253-254.

- ↑ Sarkisyanz 1965, p. 115.

- ↑ Song 1967, pp. 369–370.

- ↑ Cox 2010b, p. 176.

- ↑ Bocking 2010a, p. 232.

- ↑ Batchelor 2010.

- ↑ Turner, Cox & Bocking 2010, p. 130.

- 1 2 Bocking 2010a, p. 231.

- 1 2 Tweed 1992.

- ↑ Turner 2010, pp. 164–166.

- ↑ Cox & Griffin 2011.

- ↑ Turner, Cox & Bocking 2010, p. 143.

- ↑ Cox 2010a.

References

Books and book chapters

- Cox, Laurence (2013). Buddhism and Ireland: from the Celts to the counter culture and beyond. Sheffield: Equinox. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013.

- Cox, Laurence; Griffin, Maria (2011). "The Wild Irish Girl and the "Dalai Lama of Little Thibet": the long encounter between Ireland and Asian Buddhism". In Olivia Cosgrove; Laurence Cox; Carmen Kuhling; Peter Mulholland. Ireland's New Religious Movements. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 53–73. ISBN 978-1-4438-2588-7.

- Franck, Harry Alverson (1910). A Vagabond journey around the world; a narrative of personal experience. Garden City, NY: Garden City Publishing. Archived from the original on 7 March 2010.

- Sarkisyanz, Emanuel (1965). Buddhist backgrounds of the Burmese revolution. The Hague: M. Nijhoff. OCLC 422201772.

- Song, Ong Siang (1967). One hundred years of the Chinese in Singapore. Singapore: University of Malaya Press. ISBN 0-19-582603-5.

- Turner, Alicia (2009). Buddhism, colonialism and the boundaries of religion: Theravada Buddhism in Burma 1885–1920 (PhD dissertation). Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Tweed, Thomas (1992). The American Encounter with Buddhism, 1844–1912: Victorian Culture and the Limits of Dissent. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Conference papers

- Cox, Laurence (2010a). Plebeian freethought and the politics of anti-colonial solidarity: Irish Buddhists in imperial Asia (PDF). Fifteenth international conference on alternative futures and popular protest. Manchester Metropolitan University.

Journal articles

- Bocking, Brian (2010a). ""A man of work and few words?" Dhammaloka beyond Burma". Contemporary Buddhism. 11 (2). doi:10.1080/14639947.2010.530072.

- Cox, Laurence (2009). "Laurence O'Rourke/U Dhammaloka: working-class Irish freethinker, and the first European bhikkhu?" (PDF). Journal of Global Buddhism. 10: 135–144. ISSN 1527-6457.

- Cox, Laurence (2010b). "The politics of Buddhist revival: U Dhammaloka as social movement organiser" (PDF). Contemporary Buddhism. 11 (2): 173–227. doi:10.1080/14639947.2010.530071. ISSN 1463-9947.

- Skilton, Andrew; Crosby, Kate (2010). "Editorial". Contemporary Buddhism. 11 (2): 121–124. doi:10.1080/14639947.2010.532369.

- Turner, Alicia (2010). "The Irish Pongyi in colonial Burma: the confrontations and challenges of U Dhammaloka". Contemporary Buddhism. 11 (2): 129–172. doi:10.1080/14639947.2010.530070.

- Turner, Alicia; Cox, Laurence; Bocking, Brian (2010). "Beachcombing, Going Native and Freethinking: Rewriting the History of Early Western Buddhist Monastics" (PDF). Contemporary Buddhism. 11 (125–147). ISSN 1463-9947.

- Tweed, Thomas (2010). "Towards the study of vernacular intellectualism: a response". Contemporary Buddhism. 11 (2): 281–286. doi:10.1080/14639947.2010.530073.

Video presentations

- Bocking, Brian (20 January), The study of religions in a smart society: inaugural lecture (WMV), University College Cork Check date values in:

|date=, |year= / |date= mismatch(help) - Bocking, Brian (2011), Lost Irish Buddhist (Flash)

Other published sources

- Batchelor, Stephen (2010). "Buddhism in the west: a brief history". Boeddhistische-Unie Belgie / Union Bouddhique Belge.