USS Iowa (BB-4)

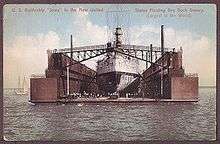

._Port_bow%2C_entering_drydock%2C_09-01-1898_-_NARA_-_535433.tif.jpg) Iowa entering drydock, 1898 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Iowa |

| Namesake: | State of Iowa |

| Builder: | William Cramp & Sons[1] |

| Cost: | $3 million[2] |

| Laid down: | 5 August 1893 |

| Launched: | 28 March 1896 |

| Sponsored by: | M. L. Drake |

| Commissioned: | 16 June 1897 |

| Recommissioned: |

|

| Decommissioned: |

|

| Renamed: | Coast Battleship No. 4 |

| Refit: | 11 June 1899 |

| Struck: | 27 March 1923 |

| Identification: | Hull symbol: BB-4 |

| Fate: | Sunk as gunnery target, 23 March 1923. |

| Class overview | |

| Preceded by: | Indiana class |

| Succeeded by: | Kearsarge class |

| General characteristics [1][3][4] [5] | |

| Type: | Pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | 11,346 long tons (11,528 t) |

| Length: | |

| Beam: | 72 ft 3 in (22.02 m)[7] |

| Draft: | 28 ft (8.5 m) (maximum)[7] |

| Installed power: | 11,000 ihp (8,200 kW) |

| Propulsion: | |

| Speed: | 17 kn (31 km/h; 20 mph) |

| Complement: | 683[7] |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

| Notes: | Armor is Harvey steel. |

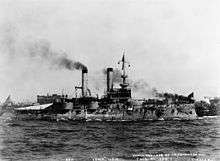

USS Iowa (BB-4) was a United States Navy battleship. It was the first ship commissioned in honor of Iowa and was America's first seagoing battleship. Iowa saw substantial action in the Spanish–American War. While she was an improvement over the Indiana class because of a superior design, the warship became obsolete quickly in the first quarter of the 20th century, and was used for target practice and sunk on 23 March 1923 in Panama Bay by a salvo of 14-inch shells.[1]

Design

On 19 July 1892, the Congress of the United States authorized a 9,000 long tons (9,100 t) warship; specifically, it was for a "seagoing coastline battleship" to fulfill the Navy's desire for a ship that could operate effectively in open waters. The preceding Indiana class, authorized by Congress as "coast-defense battleships", had many problems with endurance and speed.[8]

Iowa had a unique design and did not belong to a specific ship class,[9] but she represented an upgrade from the Indiana class.[9] Iowa's keel was built by William Cramp and Sons of Philadelphia on 5 August 1893,[1] who also built the coal-burning, 11,000 ihp (8,200 kW) vertical triple expansion reciprocating engines.[4] She carried 1,795 short tons (1,628 t) of coal. Iowa was based on the earlier Indiana-class and carried a similar armament layout; she was armed with four 12-inch (305 mm) guns in twin turrets fore and aft, supplemented by eight 8-inch (203 mm) guns in four twin turrets[10] and two above-board 14-inch (356 mm) torpedo tubes.[4] There was extensive testing of new armor plating; at one point, Iowa was fired on in testing to assess the strength of the steel shell.[11] Like Indiana, Iowa was made using "Harveyized steel".[9]

Iowa's main armor belt was 186 ft (56.7 m) long and 7 ft 6 in (2.3 m) wide, with transverse bulkheads 12 in (300 mm) thick [12] and reinforced by coal bunkers 10 ft (3.0 m) thick.[7] Above the main belt-running up to the main deck-was a short armored strake 4 in (100 mm) thick.[12]

The main battery consisted of 4 12-inch/35 caliber hydraulically powered guns–as opposed to the 13-inch (330 mm)/40 caliber guns of the Indianas.[10] The vessel had a larger margin of freeboard and a longer hull and forecastle, which resulted in greater stability.[10][13] The increased deck height-25 ft 6 in (7.8 m)[12]-made the guns less exposed to seawater, reducing the risk of malfunctions due to wet weather.[10] By utilizing the Harvey process, Iowa's armor was thinner but stronger than the nickel-steel armor used in the Indianas.[13] Compared to British warships, Iowa had excellent speed–18 kn (33 km/h; 21 mph)-but was 3,500 long tons (3,600 t) lighter.[10]

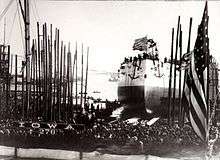

Launching

Iowa was launched on 28 March 1896, sponsored by the daughter of the Governor of Iowa named Mary Lord Drake.[1] Drake commissioned the vessel on 16 June 1897,[1][3] with Captain William T. Sampson in command.[1] Iowa was known as "Battleship No. 4" during her lifespan and redesignated BB-4 after the hull classification symbol system became standard in 1921.

Service history

Spanish–American War

After shakedown off the Atlantic coast, Iowa was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet and was sent to the Caribbean to participate in the naval campaign of the Spanish–American War, participating in the Bombardment of San Juan, Puerto Rico on 12 May 1898, and the blockade off Santiago de Cuba on 28 May 1898.[1][3] under the command of Captain Robley D. "Fighting Bob" Evans.[10][14][15] She participated in a naval bombardment of the fort near Santiago.[2] She joined many other American warships blockading Cuba, including: the battleships Massachusetts, Texas, and Oregon; the cruisers New York, Marblehead, New Orleans, and Brooklyn; the gunboat Dolphin ; the auxiliary cruisers Harvard, [16] Suwanee, and Resolute;[16] the armed yachts Vixen and Mayflower; the torpedo boat Porter; and the auxiliary coal supply ship Saint Paul.[17][18]

Sampson's blockade

The Commander in Chief of the North Atlantic Station, Rear Admiral Sampson, insisted the blockade be tight; "the escape of the Spanish vessels at this juncture would be a serious blow to our prestige, and to a speedy end to the war", he wrote.[18] He was not worried about fire from shore batteries[18] but was concerned about possible attack from a surface-going torpedo boat and urged captains to look for tell-tale signs of attacking boats such as smoke on the water.[18] One issue was having enough coal.[16] Since steam engines take time to build sufficient energy to drive larger piston engines, boilers were kept running and steam pressure raised to enable rapid start-up movement despite the usage of precious coal.[18] Luckily, vessels could coal while maintaining a position in the blockade.[18]

The initial plan was for blockading ships to wait 6 nmi (11 km; 6.9 mi) out from Santiago harbor during the day, but this was tightened to 4 nmi (7.4 km; 4.6 mi) after a while.[18] At night or in bad weather, the ships were brought in closer to prevent escapes. One squadron blocked the east side, another the west. Picket launches each evening were ordered one mile off shore.[18] The admiral gave specific instructions about how to use searchlights at night to sweep the horizon "steadily and slowly" and "not less than three minutes should be employed in sweeping through an arc of 90 degrees."[18] By 2 June 1898, Sampson headed one squadron which included New York, Iowa, Oregon, New Orleans, Mayflower, and Porter, while commander Schley headed Brooklyn, Massachusetts, Texas, Marblehead, and Vixen.[18] One squadron blocked the east side harbor exit; the other, the west.[18] By 10 June, Spanish warships in Cuba's Santiago harbor were "neatly bottled up", according to Iowa's Captain Evans.[14]

On Sunday morning, 3 July 1898, there were partly cloudy skies with fairly calm water.[19] Six Spanish warships steamed out of Santiago harbor[19] in a southwesterly direction.[16] Iowa was the first to sight black ships,[19] Spanish cruisers approaching[3] Iowa telegraphed other American ships at 09:30,[16] and fired the first shot in the Battle of Santiago.[1][3] Iowa along with Indiana, Texas, Oregon and Brooklyn chased the Spanish cruisers.[16][19] A second report includes Gloucester as being part of the chasing squadron and suggests Vixen's purpose was to protect Brooklyn from Spanish torpedo boats.[16] A third report lists torpedo boat Ericsson as participating.[16]

The two fleets engaged in a brief but intense naval battle off the shore of Cuba.[20] There was speculation that two Spanish torpedo destroyers posed a serious risk.[19] In a 20-minute battle with the cruisers Infanta Maria Teresa and Almirante Oquendo, Iowa's effective fire set both ships aflame and drove them on the beach, according to several reports.[1][16] Fire from both fleets was continuous and fast and furious.[16] The two Spanish torpedo boats took on Gloucester which prevailed against both in a tense fight.[16] Some reports suggest Iowa suffered from engine trouble during the battle and "limped along at 10 knots",[10] as well as taking two hits from the Spanish warship Colon, which further reduced her speed;[10] however, later analysis suggests Iowa was a significant participant throughout the battle and this is inconsistent with a reduced speed.[20] A dangerous fire in Iowa's lower decks broke out during the battle-possibly caused by enemy gunfire-which threatened lethal explosions, but fast and brave work by Fireman Robert Penn extinguished the blaze, possibly sparing the ship, and he was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroism.[21] US warships pursued fleeing Spanish cruisers.[10] Iowa and Gloucester sank the destroyer Pluton and damaged fellow destroyer Furor to the point where the Spanish warship ran aground.[1][10] Colon was beached also.[16] The wrecks burned fiercely.[16] Iowa then pursued the Spanish flagship-the cruiser Vizcaya-and ran her aground.[1][16] Spanish sailors on the beaches were being threatened by Cuban irregulars, but Captain Evans sent a boat ashore to warn them, and protected the captured sailors.[10]

When Vizcaya exploded and beached at Playa de Aserraderos, Iowa lowered boats to rescue Spanish crewmen from shark-infested waters.[16] Iowa received Spanish Admiral Pascual Cervera and the officers and crews of Vizcaya, Furor, and Pluton.[1] Vizcaya's Captain Don Antonio Eulate was "soaked in oil and wearing a sooty, bloodstained bandage about the head."[10] The captured captain tried to offer his sword as a gesture of surrender, but it was returned to him by Captain Evans.[10][15] Almost immediately after the Spanish captain cried "Adios, Vizcaya!", the flaming ship's magazine exploded and dramatically finished her destruction.

At one point, Iowa's Captain Evans directed Harvard to rescue prisoners.[16] Some accounts suggest that it took 12 hours to rescue all the survivors.[19] For a while, several American warships were crowded with prisoners, including Iowa.[16] A pig was rescued from Colon.[2] There were 1,612 Spanish survivors in total who became US prisoners of war until subsequent release during a prisoner exchange.[10] It was a general victory for the US Navy. One unexpected circumstance was that an Austrian battleship (actually an armored cruiser) also named Maria Theresa was in the vicinity wanting to enter Santiago harbor, but upon outbreak of hostilities, waited for orders from the Americans after seeing the conflict; her presence caused mild confusion at some points, but there is no evidence that she was ever fired on.[16]

Competing claims for credit

After the battle a mini-drama played itself out which sometimes erupted in opposing newspaper accounts.[20] Reports by several captains were published including detailed accounts from Brooklyn's Captain Cook[16] who reported his ship was hit 20 times, with one sailor killed and another wounded.[16] Reports were also filed by commanders of Resolute, Harvard, Ericsson, Vixen,[16] and later Gloucester[19] and published in the New York Times. There was no newspaper-published report of the battle from the perspective of Iowa's Captain Evans. After Admiral Sampson released his report, Indiana's Captain H.C. Taylor felt slighted and wrote "If the official record should be referred to in future it will appear from its general tone that the Indiana was less deserving than all of her consorts."[22] The admiral replied that Indiana began in the east, as instructed, which made it harder for it to join the battle; later, Indiana was ordered back to guard the harbor entrance since there was speculation that other Spanish ships might have been trying to escape, and deserved commendation for her contribution.[22] An assessment revealed the squadron guarding the westerly side of the harbor was closest to the fleeing ships and therefore saw more action. Special investigators were dispatched to examine beached Spanish warships as well as consider possibly re-floating sunken boats for further analysis.[20] Detailed diagrams were made of the destroyed ships with measurements, sometimes disputed, of the diameters of shell holes, along with counts of ammunition expended and reports by each captain.[20] (see diagram showing battle damage.) There was speculation about repairing some of the damaged Spanish warships at one point.[17] One analyst described the Maria Teresa a month after the battle as follows: "the metal was broken and twisted into a mass of junk iron" and reported that the Oquendo was "broken in two on the rocks".[17]

Analysis

After competing claims appeared in newspapers, a more definitive report emerged which gave substantial credit to Iowa and Brooklyn for inflicting "seven-tenths" of the damage to the opposing fleet.[20] Both ships were closest to the battle; Iowa expended 1,473 separate pieces of ammunition (big shells plus smaller rounds) and Brooklyn expended 1,973.[20] Other conclusions which emerged:

- The American ships were generally faster.[16] The engines of Resolute made 81 revolutions per minute (RPM), allowing the boat to speed through the water at 16 kn (30 km/h; 18 mph).[16] Naval engineers got significant credit for making fast seagoing boats.[16] Ship's engineers were honored in a dinner in New York on 1 September 1898 at the Engineers' Club, including Iowa Chief Engineer Charles W. Rae.[23] Oregon might not have even made it to the battle, but it arrived on time from San Francisco because of its speed as well as perseverance by its ships engineers and machinists.[23]

- Admiral Sampson's earlier estimate not to worry about fire from shore batteries proved correct; there was little damage to US forces from the land as well as reports of land-fired shells whizzing overhead but not striking anything.[18] A reporter aboard Gloucester said shells from a nearby Spanish fort whizzed overhead.[19]

- Spanish gunnery was poor, according to one report.[16]

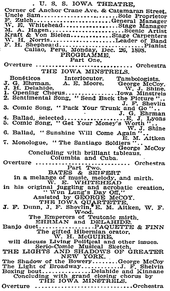

Pre-World War I

After the battle, Iowa left Cuban waters for New York City, arriving on 20 August.[1] While being towed by four tugboats to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Iowa came "very near colliding with the cruiser Chicago" after a hawser attached to one tugboat broke; a new hawser was hurriedly run out to Iowa's bow, preventing a collision.[24] On 12 October, she departed for the Pacific, sailed through the Straits of Magellan at Cape Horn.[1][25] A reporter on board describing the passage wrote "snow-capped mountains rising out of the sea, barren and gray just below the snow" along with "furious squalls called williwaws" which "picks up the water in masses of foam."[25] While stationed in Valparaíso, Chile around 17 December, and later at Callao, Peru around 26 December, the sailors of Iowa along with Oregon gave on-board self-created performances for audiences including select sailors from the navies of Chile and Peru as a way to ease tensions following the conflict over Cuba (some South Americans sided with Spain.)[25] The self-described "Iowa Minstrels" made a "melange of music, melody, and mirth" featuring a written program which included such entertainment as an overture, juggling, acrobatics, a "gifted Hibernian orator", comic sketches, singing, and banjo playing.[25] She arrived at San Francisco, California on 7 February 1899.[1] While in port, the crew presented Captain Evans with a sword bearing the inscription "To our hero—Too just to take a fallen foe's—We give this sword instead." This referred to Captain Evans' refusal to accept Captain Don Antonio Eulate's sword after the Battle of Santiago.[15] The captain thanked his crew for their bravery and respect in a published reply.[15] The battleship then steamed to Bremerton, Washington, where she entered drydock on 11 June.[1] After refit, Iowa served in the Pacific Squadron for 2 years under the command of Captain Goodrich,[2] conducting training cruises, drills, and target practice.[1] On 1 August 1900, the British cruiser HMS Phaeton narrowly avoided colliding with Iowa in the straits near Victoria (British Columbia) during a dense fog.[26] At another point during these years, a manhole plate of a boiler blew open and the determined actions of five crewmen (see below) spared the ship from further disaster.[27] Iowa left the Pacific in 1902 to become flagship of the South Atlantic Squadron.[1] She went to New York arriving February 1903 and was again decommissioned in June.[1]

Iowa recommissioned on 23 December 1903 and joined the North Atlantic Squadron.[1] She participated in the John Paul Jones Commemoration ceremonies on 30 June 1905.[1] On 23 June, Iowa was serviced in the newly built floating dry dock Dewey.[28] She remained in the North Atlantic until she was placed in reserve on 6 July 1907.[1] Future-Admiral Raymond A. Spruance served on Iowa in 1906 and 1907. She decommissioned at Philadelphia on 23 July 1908.

Iowa recommissioned on 2 May 1910[1] with a new "cage" mainmast,[3] and served as an at-sea training ship of the Atlantic Reserve Fleet for Naval Academy Midshipmen.[3] On 13 May 1911, at sea 55 nmi (102 km; 63 mi) east of Cape Charles, Virginia, she and another vessel rescued passengers from the sinking Ward liner Merida after it collided with the United Fruit Company's steamship Admiral Farragut in dense fog; all 319 passengers on Merida remained alive.[29] During the next four years, she made training cruises to Northern Europe and participated in the Naval Review at Philadelphia from 10–15 October 1912.[1] She was decommissioned at Philadelphia Navy Yard on 27 May 1914.[1]

World War I

Iowa was placed in limited commission on 28 April 1917.[1] After serving as a receiving ship at Philadelphia for six months, she was sent to Hampton Roads and remained there for the duration of the war, training men for other ships of the Fleet, and doing guard duty at the entrance to Chesapeake Bay.[1][3] She was decommissioned for the final time on 31 March 1919.[1][3]

Post–war

On 30 April 1919, Iowa was renamed Coast Battleship No. 4[1] to free her name for one of the six new South Dakota-class battleships[lower-alpha 1]

As Coast Battleship No. 4, she became the first radio-controlled target ship to be used in a fleet exercise.[1][3][21] At the Philadelphia Navy Yard, workers removed the ship's guns, sealed compartments, and installed water pumps to slow the sinking process and enable a longer target session.[21][30] They also installed radio control gear, developed by the radio engineer John Hays Hammond Jr.

She ran trials off Chesapeake Bay in 1920 with the battleship Ohio serving as control ship. Once under way, the crew left in small boats and she was fully controlled by radio signals.[21] She returned to active service in April 1922 to Hampton Roads, Virginia to take part in gunfire exercises with the minelayer Shawmut as control ship.[21]

In 1923, she went through the Panama Canal to the Pacific Ocean to take part in combined fleet maneuvers. A party of high-ranking navy officials as well as members of Congress and newspaper correspondents sailed to Panama aboard Henderson to watch the experimental firing.[31] The target ship was bombarded by 5-inch (130 mm) batteries from 8,000 yd (7.3 km) away by Mississippi.[21] Iowa was then pounded by 30 14-inch shells from a greater distance. Finally, she was bombarded by nearly three dozen heavier projectiles (weighing 0.75 short tons (680 kg) each), by a salvo of 14-inch shells and she sank in the Gulf of Panama.[1][3][21]

_underway_c1922.jpg) Aerial view of Coast Battleship No. 4

Aerial view of Coast Battleship No. 4 Coast Battleship No. 4 leaves Pedro Miguel Lock in the Panama Canal, heading for the Pacific Ocean for use as a target

Coast Battleship No. 4 leaves Pedro Miguel Lock in the Panama Canal, heading for the Pacific Ocean for use as a target_Becomes_Radio-controlled_Target_Ship_In_1923.jpg) The unmanned target ship Coast Battleship No. 4 under fire

The unmanned target ship Coast Battleship No. 4 under fire

Honors

The ornate silver service of Iowa was commissioned by the Iowa legislature and produced by J.E. Caldwell & Co. of Philadelphia for $5,000. It is now on long-term loan to the Iowa State Historical Society museum and occasionally put on display.[32]

On 25 January 1905, six of her crew—Fireman 1st Class Frederick Behne, Seaman 1st Class Heinrich Behnke, Fireman 1st Class DeMetri Corahorgi, Watertender Patrick Bresnahan, Boilermaker Edward Floyd, and Chief Watertender Johannes J. Johannessen—received the Medal of Honor for "extraordinary heroism in the resulting action" after a manhole plate of a main boiler blew open.[27]

Awards

Notes

- ↑ Like her five sisters, the new Iowa was begun but abandoned and scrapped before her completion.

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 DANFS Iowa (BB-4).

- 1 2 3 "USS IOWA (BB-4)". The Patriot Files. 8 September 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ↑ Chesneau, Koleśnik & Campbell 1979, p. 141.

- ↑ (oa)(2001) Jane's Fighting Ships of World War I, pg. . Random House, London. ISBN 1851703780

- 1 2 3 4 5 (2001) Jane's Fighting Ships of World War I, pg. 137. Random House, London. ISBN 1851703780

- ↑ Friedman 1985, pp. 29–30.

- 1 2 3 The New York Times 24 April 1896.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "U.S.S. Iowa (BB-4), 1898". City of Art. 8 September 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ↑ The New York Times 8 November 1895.

- 1 2 3 Ford, Roger (2001) The Encyclopedia of Ships, pg. 259. Amber Books, London. ISBN 9781905704439

- 1 2 Friedman 1985, p. 30.

- 1 2 The New York Times 10 June 1898.

- 1 2 3 4 The New York Times 4 April 1899.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 The New York Times 29 July 1898.

- 1 2 3 The New York Times 22 July 1989.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 The New York Times 27 July 1898.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The New York Times 24 July 1898.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The New York Times 23 April 1899.

- 1 2 The New York Times 26 August 1898.

- 1 2 The New York Times, Great Trip 2 September 1898.

- ↑ The New York Times, Narrow Escape 2 September 1898.

- 1 2 3 4 The New York Times 22 January 1899.

- ↑ The New York Times 2 August 1900.

- 1 2 "Medals of Honor winners". Iowa History Organization. 8 September 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ↑ "The Iowa (BB-04) in the New United States Floating Dry Dock Dewey (YFD-1) (Largest in the World).". The American News Company New York, Leigzig, Dresden. 23 June 1905. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ↑ The New York Times 13 May 1911.

- ↑ "U.S. Navy Gets Crewless Ghost Fleet" Popular Science, February 1932

- ↑ The New York Times 6 March 1923.

- ↑ Johnson 1992.

Print sources

- Jane's Fighting Ships of World War I. London: Random House Group, Ltd. 2001. ISBN 1-85170-378-0.

- Ford, Roger; Gibbons, Tony; Hewson, Rob; Jackson, Bob; Ross, David (2001). The Encyclopedia of Ships. London: Amber Books, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-905704-43-9.

- Alden, John D. (1989). American Steel Navy: A Photographic History of the U.S. Navy from the Introduction of the Steel Hull in 1883 to the Cruise of the Great White Fleet. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-248-2.

- Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships, An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-715-9.

- Reilly, John C.; Scheina, Robert L. (1980). American Battleships 1886–1923: Predreadnought Design and Construction. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-524-7.

- Chesneau, Roger; Koleśnik, Eugène M.; Campbell, N.J.M. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Johnson, William (1992). "The USS Iowa Silver Service Comes Home". Palimpsest: Iowa's Popular History Magazine. 73 (4): 161–169. ISSN 0031-0360.

Online sources

- "Iowa". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "USS Iowa (Battleship # 4), 1897–1923. Later renamed Coast Battleship # 4.". Department of the Navy — Naval Historical Center. 13 April 2003. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- "Coast Battleship No. 4 (ex-USS Iowa, Battleship # 4) — As a Target Ship, 1921–1923". Department of the Navy — Naval Historical Center. 13 April 2003. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- "Battleship Photo Archive BB-4 USS Iowa — 1893–1900". NavSource.com. NavSource Naval History. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Radio World may 1922 - Radio-Equipped "Iowa" to Be Sunk -page.13" (PDF). Retrieved 1 December 2014.

The New York Times

- "Our Navy and Commerce" (PDF). The New York Times. 8 November 1895. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

Discussion Before the Society of Naval Architects.—Centreboard in Yachtbuilding—W. P. Stephens Tells of Its Influence on Design—President Taylor of the War College Speaks—Use of Aluminum.

- "Indiana the Navy's pride" (PDF). The New York Times. 24 April 1896. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

Visitors Throng the Big Battleship at Brooklyn Navy Yard. An Ideal Fighting Machine Equal to Any Vessel Affoat—Her Powerful Armament—In an Engagement Lasting Thirty Minutes the Indiana Can Hurl Forty Tons of Metal—Torpedoes That Travel Thirty Miles an Hour—Perfect Discipline

- "HE HITS AT SANTIAGO; Story of the Naval Battle as Told by Charts. TWO SHIPS LEAD THE LIST Cruiser Brooklyn and Battleship Iowa Made Seven-tenths of All Marks with Big Projectiles" (PDF). The New York Times. 23 April 1899. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- "CAPT. BARKER'S SQUADRON; Uncle Sam's Sailors Entertained at Valparaiso and Callao. NAVIES OF CHILE AND PERU A Minstrel Show on the Battleship Iowa — Mountainous Scenery in the Straits of Magellan" (PDF). The New York Times. 22 January 1899. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- "FURTHER REPORTS OF THE BATTLE; Navy Department Makes Public More Santiago Accounts. CAPT. COOK'S GRAPHIC STORY Commander of the Brooklyn Describes the Great Victory. Events of the Day, as Seen from Schley's Flagship and Smaller Vessels of the Squadron" (PDF). The New York Times. 29 July 1898. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- "Capt. Evans's Ancestry (from the Scranton (Penn.) Republican)" (PDF). The New York Times. 10 June 1898. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- "A SWORD FOR CAPT. R.D. EVANS.; The Gift of the Iowa's Crew Bears a Noteworthy Inscription" (PDF). The New York Times. 4 April 1899. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- "Hobson in Washington: Warm Greetings from Officials and the Public—An Interview with the President" (PDF). The New York Times. 22 July 1989. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- "SAMPSON'S BATTLE PLANS; Copies of the Official Orders and Memoranda Issue by the Admiral Before the Engagement" (PDF). The New York Times. 27 July 1898. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- William Wallace Whitelock (sailor aboard the USS Gloucester) (24 July 1898). "HOW OUR SHIPS SANK SPAIN'S; Story of the Santiago Fight of the Gloucester. TALE OF A MAN IN ACTION The Battle of the Yacht and the Two Destroyers. Tremendous Hail of Steel from the Former Pleasure Boat — Desperate Resistance of the Brave but Hopeless Spaniards" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- "THE INDIANA AT SANTIAGO.; Admiral Sampson Assures Capt. Taylor that He Meant No Criticism in His Report" (PDF). The New York Times. 26 August 1898. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- "THE OREGON'S GREAT TRIP; Description by Chief Engineer Milligan at a Dinner to the Fleet Engineers. HEROIC EFFORTS OF HIS STAFF Machinists at Times Worked 26 Hours at a Stretch — How Capt. Clark Would Have Tackled Cervera's Squadron Had He Met It" (PDF). The New York Times. 2 September 1898. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- "The Iowa's Narrow Escape — Hawser Broke and She Was Just Prevented from Striking the Chicago" (PDF). The New York Times. 2 September 1898. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- "Warships Nearly Collide; H.M.S. Phaeton and the Iowa Only Just Escape a Disaster" (PDF). The New York Times. 2 August 1900. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- "SUNK IN SEA CRASH; 319 PERSONS SAVED" (PDF). The New York Times. 13 May 1911. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- "Congress Party Sails for Navy Manoeuvres: Will See the Old Warship Iowa Sunk by the Mississippi's Great Guns". The New York Times. 6 March 1923. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to USS Iowa (BB-4). |

- MaritimeQuest USS Iowa BB-4 Photo Gallery

- Photo gallery of Iowa at NavSource Naval History

- Naval Historical Center — USS Iowa (Battleship # 4), 1897–1923. Later renamed Coast Battleship # 4

_Warship_Design_1898.gif)