USS Cavalla (SS-244)

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Cavalla |

| Namesake: | Cavalla |

| Builder: | Electric Boat Company, Groton, Connecticut[1] |

| Laid down: | 4 March 1943[1] |

| Launched: | 14 November 1943[1] |

| Sponsored by: | Mrs. M. Comstock |

| Commissioned: | 29 February 1944[1] |

| Decommissioned: | 16 March 1946[1] |

| Recommissioned: | 10 April 1951[1] |

| Decommissioned: | 3 September 1952[1] |

| Recommissioned: | 15 July 1953[1] |

| Decommissioned: | 3 June 1968[1] |

| Reclassified: |

|

| Struck: | 30 December 1969[1] |

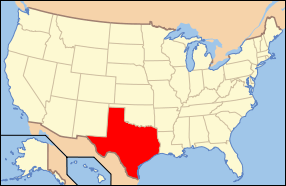

| Status: | Museum ship at Galveston, Texas as of 21 January 1971[2] |

| Notes: | Sank the IJN Carrier Shōkaku |

| Badge: |

|

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Gato-class diesel-electric submarine[2] |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 311 ft 9 in (95.02 m)[2] |

| Beam: | 27 ft 3 in (8.31 m)[2] |

| Draft: | 17 ft (5.2 m) maximum[2] |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | |

| Range: | 11,000 nmi (20,000 km) surfaced at 10 kn (19 km/h)[6] |

| Endurance: |

|

| Test depth: | 300 ft (90 m)[6] |

| Complement: | 6 officers, 54 enlisted[6] |

| Armament: |

|

|

| |

| Location | Galveston, TX |

|---|---|

| Built | 1943 |

| NRHP Reference # | 08000477 |

| Added to NRHP | 27 May 2008 |

USS Cavalla (SS/SSK/AGSS-244), a Gato-class submarine, was a ship of the United States Navy named for a salt water fish, best known for sinking the Japanese aircraft carrier Shōkaku, a veteran of the Pearl Harbor attack.

Her keel was laid down on 4 March 1943 by Electric Boat Co., Groton, Connecticut. She was launched on 14 November 1943 (sponsored by Mrs. M. Comstock), and commissioned on 29 February 1944, Lieutenant Commander (LCDR) Herman J. Kossler, USN, (Class of 1934) in command.

Operational history

Departing New London 11 April 1944, Cavalla arrived at Pearl Harbor 9 May, for voyage repairs and training. On 31 May 1944 she put to sea, bound for distant, enemy-held, waters.

First patrol

On her maiden patrol Cavalla, en route to her station in the eastern Philippines, made contact with a large Japanese task force on 17 June. Cavalla tracked the force for several hours, relaying information which contributed to the United States victory in the Battle of the Philippine Sea (commonly known as the "Marianas Turkey Shoot") on 19–20 June 1944. On 19 June she caught the carrier Shōkaku recovering planes, and quickly fired a spread of six torpedoes, with three hits. Shōkaku sank at 11°50′N 137°57′E / 11.833°N 137.950°E. After a severe depth charging by three destroyers, Cavalla escaped to continue her patrol, with relatively minor damage by depth charges from the Japanese destroyer Urakaze. The feat earned her a Presidential Unit Citation.

Second patrol

Cavalla's second patrol took her to the Philippine Sea as a member of a wolfpack operating in support of the invasion of Peleliu 15 September 1944.

Third patrol

On 25 November 1944, during her third patrol, Cavalla encountered two Japanese destroyers, and made a surface attack which blew up Shimotsuki at 02°21′N 107°20′E / 2.350°N 107.333°E. The companion destroyer began depth charging while Cavalla evaded on the surface. Later in the same patrol, 5 January 1945, Cavalla made a night surface attack on an enemy convoy, and sank two converted net tenders at 05°00′S 112°20′E / 5.000°S 112.333°E.

Fourth and fifth patrols

Cavalla cruised the South China and Java Seas on her fourth and fifth war patrols. Targets were few and far between, but she came to the aid of an ally on 21 May 1945. A month out on her fifth patrol, the submarine sighted HMS Terrapin, damaged by enemy depth charges and unable to submerge or make full speed. Cavalla stood by the damaged submarine and escorted her on the surface to Fremantle, arriving 27 May 1945.

Sixth patrol

Cavalla received the cease-fire order of 15 August while lifeguarding off Japan on her sixth war patrol. A few minutes later she was bombed by a Japanese plane that apparently had not yet received the same information, or heard the Gyokuon-hōsō. She joined the fleet units entering Tokyo Bay 31 August, remained for the signing of the surrender on 2 September, then departed the next day for New London, arriving 6 October 1945. She was placed out of commission in reserve there 16 March 1946.

Postwar

Recommissioned 10 April 1951, Cavalla was assigned to Submarine Squadron 8 and engaged in various fleet exercises in the Caribbean and off Nova Scotia. She was placed out of commission 3 September 1952 and entered Electric Boat Co. yard for conversion to a hunter-killer submarine (reclassified SSK-244, 18 February 1953). The SSK conversion included remodeling Cavalla's bow with addition of a curved bow adapted to mount a BQR-4 sonar system. The conversion included removal of two bow torpedo tubes, along with remodeling the original conning tower and bridge into the sail visible today.

Cavalla was recommissioned 15 July 1953 and assigned to Submarine Squadron 10. Her new sonar made Cavalla valuable for experimentation, and she was transferred to Submarine Development Group 2 on 1 January 1954, to evaluate new weapons and equipment, and to participate in fleet exercises. She also cruised to European waters several times to take part in NATO exercises, and visited Norfolk, Va., for the International Naval Review (11–12 June 1957). On 15 August 1959, her classification reverted to SS-244.

In November, 1961, Cavalla was ordered to Puerto Rico and provided electrical power via umbilical connection to USS Thresher (SSN-593) which had suffered a diesel generator failure while the nuclear reactor was shut down. Cavalla successfully assisted Thresher's restart of her reactor.[7] Thresher would then go on to sink 2 years later.

Fate

She was reclassified an Auxiliary Submarine AGSS-244 in July 1963. Cavalla was decommissioned and struck from the Naval Register, 30 December 1969.

On 21 January 1971, Cavalla was transferred to the Texas Submarine Veterans of World War II. She now resides at Seawolf Park on Pelican Island, just north of Galveston, Texas. Cavalla has undergone an extensive restoration process (see photos, below), and is open for self-guided tours. Among the early benefactors was then President of the Texas United States Submarine Veterans of World War II, Paul Francis Stolpman, and the former Texas secretary of state George Strake, Jr.[8]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Friedman, Norman (1995). U.S. Submarines Through 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. pp. 285–304. ISBN 1-55750-263-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775-1990: Major Combatants. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 271–273. ISBN 0-313-26202-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 275–280. ISBN 978-0-313-26202-9.

- ↑ U.S. Submarines Through 1945 p. 261

- 1 2 3 U.S. Submarines Through 1945 pp. 305–311

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 U.S. Submarines Through 1945 pp. 305-311

- ↑ The Cavalla-Thresher Incident

- ↑ "USS Cavalla: Sponsors and Contributors". cavalla.org. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to USS Cavalla (SS-244). |

- USS Cavalla Website

- history.navy.mil: USS Cavalla

- navsource.org: USS Cavalla

- hazegray.org: USS Cavalla

- USS Cavalla (SS-244) at Historic Naval Ships Association

- Kill Record: USS Cavalla

- Houston Chronicle: USS Cavalla Restoration 2016