Traditional Hausa medicine

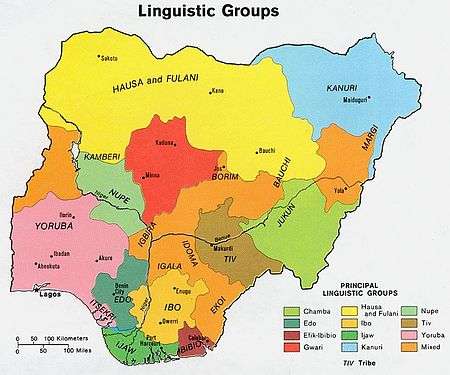

The Hausa people are an African tribe originating from what is modern-day Nigeria. Their medicine is heavily characterized by Islamic influence from the East as well as traditional African style herbology and religious practices which are still prevalent today.[1] Many traditional healing methods such as religious and spiritual healing are often used alongside more modern scientific medicine among Hausa villages and cities.[1]

Pre-Islamic influence

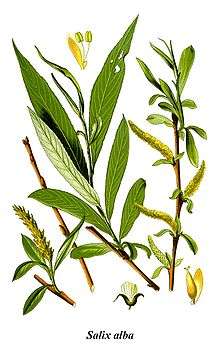

The bokaye and the yan bori are the most commonly known practitioners in Hausa society before the arrival of Islamic culture. The bokaye was an herbologist and subsisted on collecting and selling medical herbs and advice. It was common for the bokaye to be a farmer of his own medicinal herbs.[2] The practices and philosophies of the bokaye open a proverbial window into the Hausa past before the influence of Islam became the norm amongst the African tribe. The bokaye was not a spiritual healer; medicine relied on herbs and was only used for minor ailments such as headaches or upset stomachs. Spiritual healing was carried out by a yan bori or a dan bornu, a practice which did not continue after Islam took root in Hausa society.[2] The herbs that the bokaye used, and likely still use, are kept secret from the buyer. To this day it is difficult to determine just how well the herbs work as a healing agent due to the bokaye not revealing the ingredients of their medicines.[3] The secrecy of the bokaye creates an inability to determine the effectiveness of Hausa traditional medicine. The herbology used by the bokaye, however, was very well developed for its time, as the healer would have known exactly how to use specific parts of a plant, its seasons and harvesting conditions, and where it grew in the wild as well as how to farm it. They even knew how to detoxify certain plants by controlling their pollination, or by cross-pollinating them with less potent plants in order to attain a more usable medicine.[4]

The yan bori, which also survived into the Islamic societal shift, is another window into the Hausa past, but is a spiritual rather than an herbal healing practitioner. The yan bori were pagans, as were the Hausa. The spirits which the yan bori, as well as the Hausa people, worshipped before Islamic religion was adapted by Hausa society, were representative of certain aspects of Hausa life. Examples of these spirits include Dogon Daji, the Tall One of the Forest; Sarkin Rafi, the Chief of the River, Kure the Hyena; and Gajjimare, the God of Rain and Storm.[2] The yan bori would pray and perform rituals to spirits based on the patient’s ailment. The yan bori believed in spiritual possession and though they had many named spirits to govern over the world, they also believed in nameless spirits which could possess a man and must be cleansed from his body.[5] This faith healing would not uncommonly be accompanied by herbal medicine from a bokaye, assuming the patient could afford to visit both. The yan bori’s survival into the Hausa society’s adaptation of Islam was facilitated by their willingness to adopt more contemporary, and Muslim, spirits as the societal shift began to occur.[2]

Islamic influence

Islamic influence over the Hausa came in approximately the 9th century and was adopted by the king of Kanem Bornu, a large Hausa kingdom in western Africa. However, Islamic medicine as a religious healing method didn’t take hold in Hausa society until the 16th century.[2] Due to this cultural shift in the Hausa kingdoms, there are two groups of healers defined by their practices and methodology. First are the healers who specialized in the use of herbs and prayer as a means to heal, called the malam and the yan bori.[2] Secondly were the healers who specialized in minor ailments and surgeries, a far more scientific group; their titles included bokaye, masu magani, wanzamai, madorai, and malamai ungozomai.[2]

Although surgeries were performed by the Hausa before and after Islamic influence, they were always very minor, things such as circumcision or removing small abnormal growths. Due to Islamic medical practices, the development of surgery didn’t continue to progress. As Ismail Mussein writes,

"The absence of surgery in Hausa medical compilations should not surprise anyone familiar with Islamic medicine on which these writers heavily depended. Islamic medicine is deficient in writings on general surgery. Apart from Kitab al-Tasrif of the Spanish physician Abul Qasim on surgery, which at any rate, went unnoticed by the rest of the Islamic world, there is hardly any work on the subject worth noting."[2]

Islamic influence over Hausa medicine meant that surgery wasn't pursued, and didn't change. Due to the stagnation of Islamic academia in the Middle East and the spread of the religious ideology to such a remote location as northern Nigeria, the development of medical practices was slower. However, the wealth of pre-existing knowledge that Islam brought to the Hausa, such as ancient Greek practices which had been preserved by Islamic universities, helped to invigorate Hausa medicine, even though it didn’t then build upon that base knowledge.[2] Islamic influence did bring new ideas to the Hausa, however, such as the establishment of hospitals, the use of more modernized doctors rather than herbologists peddling on the streets, and the idea of disease expanding to include more pointed disease and diagnosis[2] (for example, instead of using an herb for headaches in general, trying to determine the cause of the headache and prescribing medicine based on the cause rather than the symptom).

Modern-day use

Westernized medicine does not have a long history in Nigeria or for the Hausa people. The medicine and practices of the west were introduced as recently as fifty years ago and, due to strong cultural and religious resistance, it hasn’t become the predominant medical force that the Hausa people rely on.[2] Despite the fact that western medicine has helped the people of Nigeria, including the Hausa, stave off a number of diseases such as cholera, leprosy, and malaria,[2] traditional (that is to say non-western) medicine is still considered to be the singular means by which disease is to be treated.

Traditional medicine is still widely popular amongst the Hausa peoples, with 55.8% reporting that they use both modern Western medicine and more traditional herbology and Islamic faith healing.[1] The popular use of multiple forms of medicine is a direct continuation of the Hausa medical tradition in which they still relied on their herbologists while also seeking spiritual healing from Islamic healers, or even from more traditional yan bori healers that had adapted to utilize Islamic spirits rather than their original pagan spirits. Even though western medicine has become a factor in Nigeria, the Islamic influence of the Hausa people still persists. British residents of Nigeria, for example, segregated lepers from society; however, Hausa leaders pressed to take in and look after the sick in accordance with Islamic traditions.[6]

Traditional medicine has remained popular due to its success and cheapness as well. For instance, in the case of one young Hausa girl, the nurse assigned to care for her during a severe bout of diarrhea began a treatment of rehydration and demonstrating how to remain hydrated until the severity had passed, or the illness as a whole. However, the girl’s mother would not bring her to a hospital and continued to use herbal remedies reminiscent of bokaye tradition, and it was believed by the mother that although the western medicine helped, it was her medicine that did all the healing.[7]

This practice of utilizing both forms of medicine has caused concern among western doctors who fear that herbal medicines may interfere with, or have detrimental reactions with, pharmacological medicines.[1] Of the people who seek medical attention from both traditional healers and modern western doctors, there is no abundance of evidence to suggest that variables in income, religion, education or occupation affect individual decisions to seek out two different methods of healing.[1] Rather it appears that if both approaches to healing are available, then a majority of Hausa will take advantage of both. The rate of Hausa who used both systems of treatment were significantly higher in urban areas where the availability of both was more common, as opposed to rural Hausa who would only have access to one form of medicine.[1]

Practitioners of Hausa herbology in modern Nigeria are educated in the Islamic sciences and Arabic from a young age. Studying numerology and astrology is also common.[2] These healers thrive by traveling between towns and selling herbal remedies to poor people who cannot afford to visit a hospital, going to populated areas where the medical facilities cannot meet the demands of the people living around them, or by seeing to the desires of people who prefer to rely on a more traditional method of healing than what western medicine provides.[2]

AIDS/HIV

The AIDS/HIV epidemic in Africa is no stranger to the Hausa people, who are experiencing a divide amongst treatment. Many Hausa sufferers of AIDS rely on traditional Islamic spiritual healing methods. However, many rely on western medicine, as antiretroviral treatment and biomedical institutions become more available and affordable to patients looking for relief from their symptoms.[8] Western hospitals and facilities for AIDS and HIV treatment treat ART as the singular best way to treat the disease,[8] and make little to no exception for Hausa tradition, which makes modern treatment less popular amongst Islamic Hausa people. ART is also made unavailable to Islamic healers and doctors who don’t conform to the methodology and practices of western medicine. However they also don’t show much, if any, interest in distributing the medicine, since it doesn’t align with Islamic customs and the deeply rooted customs and values of Hausa society.[8]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nnadi, Eucharia E.; Hugh F. Kabat (January 1984). "Nigerians' Use of Native and Western Medicine for the Same Illness". Public Health Reports. 99 (1): 93–98.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Mussein, Ismail (1981). Islamic Medicine And Its Influence on Traditional Hausa Practitioners in Northern Nigeria. USA: University of Wisconsin-Madison. p. 251.

- ↑ Waldram, James B. (December 2000). "The Efficacy of Traditional Medicine: Current Theoretical and Methodological Issues". Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 14 (4): 603–625. doi:10.1525/maq.2000.14.4.603.

- ↑ Etkin, Nina L. (1988). "ETHNOPHARMACOLOGY: Biobehavioral Approaches in the Anthropological Study of Indigenous Medicines". Annual Review of Anthropology. 17: 23–42. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.17.100188.000323.

- ↑ Last, Murray (August 2011). "Another geography: risks to health as perceived in a deep-rural environment in Hausaland". Anthropology & Medicine. 18 (2): 217–229. doi:10.1080/13648470.2011.591198.

- ↑ SHANKAR, SHOBANA (2007). "MEDICAL MISSIONARIES AND MODERNIZING EMIRS IN COLONIAL HAUSALAND: LEPROSY CONTROL AND NATIVE AUTHORITY IN THE 1930S". The Journal of African History. 48 (01): 45. doi:10.1017/S0021853706002489.

- ↑ Chmielarczyk, Vincent (1991). "Transcultural Nursing: Providing Culturally Congruent Care to the Hausa of Northwest Africa". Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 3 (1): 15–19. doi:10.1177/104365969100300104.

- 1 2 3 Tocco, Jack Ume (1 December 2010). "'Every disease has its cure': faith and HIV therapies in Islamic northern Nigeria". African Journal of AIDS Research. 9 (4): 385–395. doi:10.2989/16085906.2010.545646.