Cleveland Torso Murderer

| The Cleveland Torso Murderer | |

|---|---|

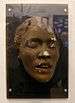

An exposition dedicated to the Cleveland Torso Murders at the Cleveland Police Museum. (from left to right: Death masks of the victims Andrassy, Polillo, "tattooed man"/#4, Wallace? #8) | |

| Other names | Cleveland Torso Murderer, Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run |

| Killings | |

| Victims | 12–20[1] |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Cleveland, Ohio |

The Cleveland Torso Murderer (also known as the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run) was an unidentified serial killer who killed and dismembered at least 12 victims in the Cleveland area in the 1930s.

Murders

The official number of murders attributed to the Cleveland Torso Murderer is twelve, although recent research has shown there are as many as twenty. The twelve victims were killed between 1935 and 1938, but some, including lead Cleveland Detective Peter Merylo, believe that there may have been 13 or more victims in the Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Youngstown, Ohio, areas between the 1920s and 1950s. Two strong candidates for addition to the initial list of those killed are the unknown victim nicknamed the "Lady of the Lake", found on September 5, 1934, and Robert Robertson, found on July 22, 1950.

The victims of the Cleveland Torso Murderer were usually drifters whose identities were never determined, although there were a few exceptions (victims numbers 2, 3, and 8 were identified as Edward Andrassy, Florence Polillo, and possibly Rose Wallace, respectively). Invariably, all the victims, male and female, appeared to hail from the lower class of society—easy prey in Depression-era Cleveland. Many were known as "working poor", who had nowhere else to live but the ramshackle shanty towns in the area known as the Cleveland Flats.

The Torso Murderer always beheaded and often dismembered his victims, sometimes also cutting the torso in half; in many cases the cause of death was the decapitation itself. Most of the male victims were castrated, and some victims showed evidence of chemical treatment being applied to their bodies. Many of the victims were found after a considerable period of time following their deaths, sometimes a year or more. This made identification nearly impossible, especially since the heads were often not found.

During the time of the "official" murders, Eliot Ness held the position of Public Safety Director of Cleveland, a position with authority over the police department and ancillary services, including the fire department.[2] While Ness had little to do with the investigation, his posthumous reputation as leader of The Untouchables has made him an irresistible character in modern "torso murder" lore. Ness did contribute to the arrest and interrogation of one of the prime suspects, Dr. Francis E. Sweeney, as well as the demolition and burning of the Kingsbury Run, from which the killer took his victims. At one point in time, the killer even taunted Ness by placing the remains of two victims in full view of his office in city hall.[1][3]

Victims

Most researchers consider there to be twelve definite victims, although new evidence suggests a woman dubbed "The Lady of the Lake" could be included. Only two victims were positively identified; the other ten were six John Does and four Jane Does.

| Order of discovery | Victim | Date found | Location | Autopsy report | Estimated time of death | Date of murder | Probable order of murder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Edward Andrassy |

September 23, 1935 | Jackass Hill area of Kingsbury Run (near East 49th and Praha Avenue) | Andrassy was found lying about 30 feet (9.1 m) from John Doe I. He had been decapitated and emasculated. His head was recovered. | Two to three days | September 1935 | 2 |

| 2 | John Doe I | September 23, 1935 | Jackass Hill area of Kingsbury Run | Male body was never identified. Emasculated and decapitated, head recovered. The skin was treated with a chemical agent that caused it to become reddish and leathery. | Initial estimates were seven to ten days. It was later revised to three to four weeks. | August/September 1935 | 1 |

| 3 | Florence Genevieve Polillo (alias Martin) |

January 26/February 7, 1936 | Between 2315 and 2325 East 20th Street in downtown Cleveland and 1419 Orange Avenue | Her body had been dismembered,the head never recovered. | Two to four days | January 1936 | 3 |

| 4 |  John Doe II "The Tattooed Man" |

June 5, 1936 | Kingsbury Run | The victim was decapitated while alive. His head was recovered. †[›] | Two days | June 1936 | 5 |

| 5 | John Doe III | July 22, 1936 | Big Creek area of Brooklyn, west of Cleveland | The victim was dismembered while still alive. His head was recovered. This unidentified male body was the only known West Side victim. | Two months | May 1936 | 4 |

| 6 | John Doe IV | September 10, 1936 | Kingsbury Run | Only half the torso was found. Nothing remained below the hips. The head was never found or the body identified. | Two days | September 1936 | 7 |

| 7 | Jane Doe V | February 23, 1937 | Euclid Beach on the Lake Erie shore | The unidentified female body was found at the same spot as the 1934 noncanonical victim nicknamed "The Lady of the Lake" (see below). The head was never found. | Three to four days | February 1937 | 8 |

| 8 |  Jane Doe VI |

June 6, 1937 | Beneath the Lorain-Carnegie bridge | Only black victim. The body was decapitated and missing a rib. The head was recovered. ‡[›] | One year | June 1936 | 6 |

| 9 | John Doe VII | July 6, 1937 | Pulled out of Cuyahoga River in the Cleveland Flats | Body of this male was recovered but the head was never found. | Two to three days | July 1937 | 9 |

| 10 | Jane Doe VIII | April 8, 1938 | Cuyahoga River in the Cleveland Flats | On April 8 only the victim's lower leg was recovered. On May 2 a human thigh was discovered floating in the river to the east of the West 3rd Street bridge. A police search under the bridge found a burlap sack containing the victim's headless torso cut in to halves, another thigh and a left foot. The head and the rest of the body were never found. Only victim to have drugs in her system.[4] | Three to five days | April 1938 | 12 |

| 11 | Jane Doe IX | August 16, 1938 | East 9th Street Lakeshore Dump | Decapitated female body. Head recovered. | Four to six months | February–April 1938 | 11 |

| 12 | John Doe X | August 16, 1938 | East 9th Street Lakeshore Dump | Discovered at the same time as Jane Doe IX. Male decapitated body. Head was found in a can. Victim never identified. | Seven to nine months | November 1937 – January 1938 | 10 |

^ †: The victim, who was estimated to be in his mid twenties, had six unusual tattoos on his body. One included the names "Helen and Paul" and another had the initials "W.C.G." His undershorts bore a laundry mark indicating the owner's initials were J.D. Despite morgue and death mask inspections by thousands of Cleveland citizens in the summer of 1936 at the Great Lakes Exposition, the victim known as the "tattooed man" was never identified.

^ ‡: Victim was possibly “Rose Wallace”. Dental work was considered a close match by police and her son (who said he was certain that the victim was his mother). Exact identification could not be achieved because the dentist who carried out the work had died years before. Doubts remained, because the body was estimated to have been dead for a year whereas Wallace had only been missing for 10 months.

Edward Andrassy was buried in St Mary Cemetery, Cleveland, Ohio;[5] Florence Pollila is buried in Pennsylvania[6] Five of the John/Jane Does {"Lady of the Lake"; and victims John Doe #1; John Doe# 2; John Doe # IV; Jane Doe #5} were buried in Potter's Field Section of Highland Park Cemetery, Highland Park, Cuyahoga County Ohio.[7] Jane Doe VI/Rose Wallace ? remains were donated to Western Reserve University Medical School[8]

Possible victims

Several non-canonical victims are commonly discussed in connection with the Torso Murderer. The first was nicknamed the "Lady of the Lake" and was found near Euclid Beach on the Lake Erie shore on September 5, 1934, at virtually the same spot as canonical victim number 7. Some researchers of the Torso Murderer's victims count the "Lady of the Lake" as victim number 1, or "Victim Zero".

A headless, unidentified male was found in a boxcar in New Castle, Pennsylvania, on July 1, 1936. Three headless victims were found in boxcars near McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania, on May 3, 1940. All bore similar injuries to those inflicted by the Cleveland killer. Dismembered bodies were also found in the swamps near New Castle between the years 1921 and 1934 and between 1939 and 1942. In September 1940 an article in the New Castle News refers to the killer as "The Murder Swamp Killer". The almost identical similarities between the victims in New Castle to those in Cleveland, Ohio, coupled with the similarities between New Castle's Murder Swamp and Cleveland's Kingsbury Run, both of which were directly connected by a Baltimore and Ohio Railroad line, were enough to convince Cleveland Detective Peter Merylo that the New Castle murders were the work of the "Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run". Merylo was convinced the connection was the railroad that ran twice a day between the two cities; he often rode the rails undercover looking for clues to the killer's identity.

On July 22, 1950, the body of 41-year-old Robert Robertson was found at a business at 2138 Davenport Avenue in Cleveland. Police believed he had been dead six to eight weeks and appeared to have been intentionally decapitated. His death appeared to fit the profile of other victims: He was estranged from his family, had an arrest record and a drinking problem, and was on the fringes of society. Despite widespread newspaper coverage linking the murder to the crimes in the 1930s, detectives investigating Robertson's death treated it as an isolated crime.[9]

In 1939 the "Torso Killer" claimed to have killed a victim in Los Angeles, California. An investigation uncovered animal bones.[10]

Suspects

On August 24, 1939, a Cleveland resident named Frank Dolezal, 52, was arrested as a suspect in Florence Polillo's murder; he later died under suspicious circumstances in the Cuyahoga County jail. After his death it was discovered that he had suffered six broken ribs—injuries his friends say he did not have when arrested by Sheriff Martin L. O'Donnell some six weeks prior.[11] Most researchers believe that no evidence exists that Dolezal was involved in the murders, although at one time he did admit killing Flo Polillo in self-defense. Before his death, he recanted his confession and recanted two others as well, saying he had been beaten until he confessed.[11]

Most investigators consider the last canonical murder to have been in 1938. One suspected individual was Dr. Francis E. Sweeney.[12] Sweeney was a veteran of World War I who was assigned in a medical unit that conducted amputations and patching in the field. Sweeney was later personally interviewed by Eliot Ness, who oversaw the official investigation into the killings in his capacity as Cleveland's Safety Director. During this interrogation, Sweeney is said to have "failed to pass" two very early polygraph machine tests. Both tests were administered by polygraph expert Leonard Keeler, who told Ness he had his man. Nevertheless, Ness apparently felt there was little chance of obtaining a successful prosecution of the doctor, especially as he was the first cousin of one of Ness's political opponents, Congressman Martin L. Sweeney, who had hounded Ness publicly about his failure to catch the killer.[12] {Congressman Sweeney was also related by marriage to Sherriff O'Donnell}. After Dr. Sweeney committed himself, there were no more leads or connections that police could assign to him as a possible suspect. From his hospital confinement, threatening postcards with Sweeney's name mocked and harassed Ness and his family into the 1950s.[12][13] He died in a veterans' hospital at Dayton in 1964.[12]

In 1997, another theory postulated that there may have been no single Butcher of Kingsbury Run because the murders could have been committed by different people. This was based on the assumption that the autopsy results were inconclusive. First, Cuyahoga County Coroner Arthur J. Pearce may have been inconsistent in his analysis as to whether the cuts on the bodies were expert or slapdash. Second, his successor, Samuel Gerber, who began to enjoy press attention from his involvement in such cases as the Sam Sheppard murder trial, garnered a reputation for sensational theories. Therefore, the only thing known for certain was that all the murder victims were dismembered.[14]

In popular culture

- Butcher's Dozen (1988) is the second of four novels by Max Allan Collins fictionalizing Ness's tenure as Cleveland's Public Safety Director. Changing some names, and reordering some events for dramatic purposes, it concludes that, although Ness was unable to actually name the killer publicly, he did identify him and made sure he was no longer a danger to the public. The novel was expanded from a short story, "The Strawberry Teardrop" (1984), in which the main character is Collins's private eye hero, Nate Heller, and Ness plays a supporting role.

- David Fincher planned to make a film about the murders after making a movie about another unidentified serial killer, known as the Zodiac Killer. A graphic novel entitled Torso, created by Brian Michael Bendis and Marc Andreyko, became the source for the film. The adaptation was greenlit by Paramount Pictures in 2006[15] but eventually cancelled. In 2013, the plan to make the film was revived, and it was reported that David Lowery would direct the film.[16]

- In 2015 Canadian band The Black River Drifters from Winnipeg, Manitoba released the single The Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run from their album Hearts Gone Cold.

- Author William Bernhardt wrote a novel about the murders and Elliot Ness' involvement, titled Nemesis: the Final Case of Elliot Ness. Although generally non-fiction, it was written as a novel, and makes some assumptions. The only significant deviation from the true story is the ending. A climax is fictionalized where Ness confirms the killer was Sweeney, and captures him, but is prevented from arresting him due to political pressure. It does try to remain factual to the case otherwise, while still remaining entertaining. NBC is currently in the works to adapt this book into a mini-series. No release date or cast has been announced as of January 2014.

- In the 2012 film Seven Psychopaths, the Cleveland Torso Murderer (described as the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run) is one of the serial killers murdered by Zachariah Rigby and his accomplice.

- The Cleveland Torso Murderer (referred to as the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run) was mentioned in episode 415 of Criminal Minds when a serial killer copying other serial killers with each kill bases one of his murders after the aforementioned murderer. The murderer was also seen in a flashback in the same episode, in which he lured a victim. It was erroneously mentioned that the murderer lured his victims from gay bars before shooting, dismembering, and mutilating them. Also, Steven Parkett, who appeared in the Season Ten premiere, was heavily based on the murderer, even having a nickname similar to the murderer's alternate nickname ("The Mad Butcher of Bakersfield")

See also

- The Black Dahlia, a Los Angeles murder case that some investigators have suggested may have been committed by the same killer.[12]

References

Citations

- 1 2 The Real Eliot Ness: A Most Merry and Illustrated History of The Untouchables and After

- ↑ Heimel, Paul (1997). Eliot Ness: The Real Story. Coudersport, PA: Knox Books. ISBN 0-9655824-0-X.

- ↑ "Haunted History – Season 1 Episode 6 The Torso Murders"

- ↑ Badal 2001, Drugs and the Maiden.

- ↑ Find a Grave

- ↑ Find a grave

- ↑ Find a grave

- ↑ Find a grave

- ↑ Badal 2001, pp. 160–165.

- ↑ Cleveland Press report 1939

- 1 2 Badal 2001, Frank Dolezal

- 1 2 3 4 5 Badal 2001, Dr. Francis Edward Sweeney

- ↑ Pile of bones: Eliot Ness hunted Cleveland serial killer, but mystery remains

- ↑ Bellamy, John (1997). The Maniac in the Bushes. Cleveland, Ohio: Gray & Co. ISBN 1-886228-19-1.

- ↑ Mark H. Harris. "10 of the Greatest Horror Movies Never Made". About.com Guide. About.com. Retrieved 2013-07-16.

- ↑ Fischer, Russ (2013-04-17). "David Lowery Takes Over 'Torso' Graphic Novel Adaptation". /Film. Retrieved 2013-07-16.

Bibliography

- Collins, Max Allan (1988). Butcher's dozen: an Eliot Ness novel. Toronto New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 9780553261516. Paperback.

- Brady, Ian (2001). The gates of Janus: serial killing and its analysis. Los Angeles, California: Feral House. ISBN 9780922915736. Hardback.

- Badal, James Jessen (2001). In the wake of the butcher Cleveland's torso murders. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 9781612772769.

- Mark Wade Stone (director) (2004). The fourteenth victim – Eliot Ness and Torso Murders (Media notes). David A. Brodowski (director of photography), Marie Studniarz Rudolph (associate producer), Carl Michel (music). Cleveland, Ohio: Storytellers Media Group. ISBN 0974957534.

- Bellamy, John (1997). The maniac in the bushes and more tales of Cleveland woe: true crimes and disasters from the streets of Cleveland. Cleveland, Ohio: Gray and Company. ISBN 9781886228191. Paperback.

- Nickel, Steven (1989). Torso: the story of Eliot Ness and the search for a psychopathic killer. Winston-Salem, North Carolina: John F. Blair Publishers. ISBN 9780895872463. Paperback, second edition 2002.

- Cooke, John (1993). Torso. London: Headline Book Publishing. ISBN 9780747241935. Paperback.

- Black, Lisa (2010). Trail of blood. New York, New York: William Morrow. ISBN 9780061989339. Hardback.

- Rasmussen, William (2005). Corroborating evidence II: the Cleveland torso murders, the Black Dahlia murder, the zodiac killer, the phantom killer of Texarkana. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Sunstone Press. ISBN 9780865345362. Paperback.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cleveland Torso Murderer. |

- Cleveland Torso Murders

- Google Map of the Torso Murders

- Cleveland Police Historical Society and Museum

- The Kingsbury Run Murders

- Torso Killer at DMOZ

- Encyclopedia of Cleveland History