Themes in Blade Runner

Despite the initial appearance of an action film, Blade Runner operates on an unusually rich number of dramatic levels.[1] As with much of the cyberpunk genre, it owes a large debt to film noir, containing and exploring such conventions as the femme fatale, a Chandleresque first-person narration in the Theatrical Version, and the questionable moral outlook of the hero — extended here to include even the literal humanity of the hero, as well as the usual dark and shadowy cinematography.

Some have said Blade Runner thematically enfolds moral philosophy and philosophy of mind implications of the increasing human mastery of genetic engineering, within the context of classical Greek drama and its notions of hubris[2] — and linguistically, drawing on the poetry of William Blake and the Bible. This is a theme subtly reiterated by the chess game between J.F. Sebastian and Tyrell based on the famous Immortal Game of 1851 symbolizing the struggle against mortality imposed by God.[3] The Blade Runner FAQ offers further interpretation of the chess game, saying that it "represents the struggle of the replicants against the humans: the humans consider the replicants pawns, to be removed one by one. The individual replicants (pawns) are attempting to become immortal (a queen). At another level, the game between Tyrell and Sebastian represents Batty stalking Tyrell. Tyrell makes a fatal mistake in the chess game, and another fatal mistake trying to reason with Batty."[3]

Blade Runner depicts a future whose fictional distance from present reality has grown sharply smaller as 2020 approaches. The film delves into the future implications of technology on the environment and society by reaching into the past using literature, religious symbolism, classical dramatic themes and film noir. This tension between past, present and future is apparent in the retrofitted future of Blade Runner, which is high-tech and gleaming in places but elsewhere decayed and old.

A high level of paranoia is present throughout the film with the visual manifestation of corporate power, omnipresent police, probing lights; and in the power over the individual represented particularly by genetic programming of the replicants. Control over the environment is seen on a large scale but also with how animals are created as mere commodities. This oppressive backdrop clarifies why many people are going to the off-world colonies, which clearly parallels the migration to the Americas. The popular 1980s prediction of the United States being economically surpassed by Japan is reflected in the domination of Japanese culture and corporations in the advertising of LA 2019. The film also makes extensive use of eyes and manipulated images to call into question reality and our ability to perceive it.

This provides an atmosphere of uncertainty for Blade Runner's central theme of examining humanity. In order to discover replicants a psychological test is used with a number of questions focused on empathy; making it the essential indicator of someone's "humanity". The replicants are juxtaposed with human characters who are unempathetic, and while the replicants show passion and concern for one another, the mass of humanity on the streets is cold and impersonal. The film goes so far as to put in doubt the nature of Rick Deckard and forces the audience to reevaluate what it means to be human.[4]

Genetic engineering and cloning

The first draft of the entire human genome was decoded on June 26, 2000, by the Human Genome Project, followed by a steadily increasing number of other organisms across the microscopic to macroscopic spectrum. The short step from theory to practice in using genetic knowledge was taken quickly: genetically modified organisms have become a present reality.

The embryonic techniques of somatic cell nuclear transfer from a specific genotype via cloning, as well as some of the problems pre-figured in Blade Runner, were demonstrated by the cloning of Dolly the sheep in 1996. Since 2001, political efforts have been mounting in many countries to ban human cloning, impelled by a sense of its abhorrence and imminence, while rumors abound that the first human clones may already have been produced, the most famous example being a claim by the extraterrestrial worshiping Raelians, a religious group who have offered no proof to support their extraordinary claims. In all of these developments, a clear tension between commercial and non-commercial interests is apparent, as scientific and business motivations conflict with ethical and religious concerns about the appropriateness of human intervention in the deepest fabric of nature. In many ways Blade Runner serves as a cautionary tale in the tradition of Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein.[2]

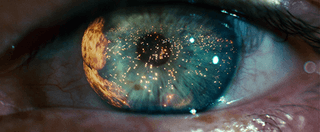

Eye symbolism appears repeatedly in Blade Runner and provides insight into themes and characters therein. The film opens with an extreme closeup of an eye which fills the screen reflecting the industrial landscape seen below. When reflecting one of the Tyrell Corp. pyramids it evokes the all-seeing Eye of Providence.[5]

In Roy's quest to "meet his maker" he seeks out Chew, a genetic designer of eyes, who created the eyes of the Nexus-6. When told this, Roy quips, "Chew, if only you could see what I've seen with your eyes", ironic in that Roy's eyes are Chew's eyes since he created them, but it also emphasizes the importance of personal experience in the formation of self. Roy and Leon then intimidate Chew with disembodied eyes and he tells them about J.F. Sebastian.

It is symbolic that the man who designed replicant eyes shows the replicants the way to Tyrell. Eyes are widely regarded as "windows to the soul", eye contact being a facet of body language that unconsciously demonstrates intent and emotion and this is used to great effect in Blade Runner. The Voight-Kampff test that determines if you are human measures the emotions, specifically empathy through various biological responses such as fluctuation of the pupil and involuntary dilation of the iris. Tyrell's trifocal glasses are a reflection of his reliance on technology for his power and his myopic vision. Roy eye gouges Tyrell with his thumbs while killing him, a deeply intimate and brutal death that indicates judgement of Tyrell's soul.

The glow which is notable in replicant eyes in some scenes creates a sense of artificiality. According to Ridley Scott, "that kickback you saw from the replicants' retinas was a bit of a design flaw. I was also trying to say that the eye is really the most important organ in the human body. It's like a two-way mirror; the eye doesn't only see a lot, the eye gives away a lot. A glowing human retina seemed one way of stating that".[2] He considers the glow to be a stylistic device only, but Brion James (Leon) suggests that pollution was the "cause" for the glow.[6]

The relationship between sight and memories is referenced several times in Blade Runner. Rachael's visual recollection of her memories, Leon's "precious photos", Roy's discussion with Chew and soliloquy at the end, "I've seen things you people wouldn't believe". However, just as prevalent is the concept that what the eyes see and the resulting memories are not to be trusted. This is a notion emphasized by Rachael's fabricated memories, Deckard's need to confirm a replicant based on more than appearance, and even the printout of Leon's photograph not matching the reality of the Esper visual.

Also in the Director's Cut, when at the Tyrell corporation the owl's eyes flicker with a red tint. This was derived from Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, in which real animals are rare and owls are very rare, since they were the first animals to start dying of the pollution which pushed humans Off-World. The red tint indicates that the owl is a replicant.

Religious and philosophical symbolism

There is a subtext of Christian allegory in Blade Runner, particularly in regard to the Roy Batty character. Given the replicants' superhuman abilities, their identity as created beings (by Tyrell) and "fall from the heavens" (off-world) makes them analogous to fallen angels. In this context, Roy Batty shares similarities with Lucifer as he prefers to "reign in hell" (Earth) rather than "serve in heaven".[7] This connection is also apparent when Roy deliberately misquotes William Blake, "Fiery the angels fell..." (Blake wrote "Fiery the angels rose..." in America, A Prophecy). Nearing the end of his life, Roy creates a stigmata by driving a nail into his hand, and becomes a Christ-like figure by sacrificing himself for Deckard. Upon his death a dove appears to symbolise Roy's soul ascending into the heavens.[8]

Zhora's gunshot wounds are both on her shoulder blades. The end result makes her look like an angel whose wings have been cut off. Zhora makes use of a serpent that "once corrupted man" in her performance.

A Nietzschean interpretation has also been argued for the film on several occasions. This is especially true for the Batty character, arguably a biased prototype for Nietzsche's Übermensch—not only due to his intrinsic characteristics, but also because of the outlook and demeanor he displays in many significant moments of the film. For instance:

- A modern audience might admire Batty’s will to flee the confinements of slavery and perhaps sympathize with his existential struggle to live. Initially, however, his desire to live is subsumed by his desire for power to extend his life. Why? In Heidegger’s view, because death inevitably limits the number of choices we have, freedom is earned by properly concentrating on death. Thoughts of mortality give us a motive for taking life seriously. Batty’s status as a slave identifies him as an object, but his will to power casts him as an agent and subject in the Nietzschean sense. His physical and psychological courage to rebel is developed as an ethical principle in which he revolts against a social order that has conspired against him at the genetic, cultural, and political levels. In Heidegger’s view, Batty’s willingness to defy social conformity allows for him to authentically pursue the meaning of his existence beyond his programming as a soldier. Confronting his makers becomes part of his quest, but killing them marks his failure to transcend his own nature.[9]

Environment and globalization

Orson Scott Card wrote of the film, "It takes place in Los Angeles. No aliens at all. But it isn't the L.A. we know ... things have changed. Lots of things, moving through the background of the film, give us a powerful sense of being in a strange new place".[10] The climate of the city in A.D. 2019 is very different from today's. It is strongly implied that industrial pollution has adversely affected planet Earth's environment, i.e. global warming and global dimming. Real animals are rare in the Blade Runner world. In Philip K. Dick's 1968 novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, animal extinction and human depopulation of the planet were consequent to the radioactive fallout of a nuclear war;[11] Owls were the first species to become extinct. This ties in with Deckard's comment about Dr. Tyrell's artificial owl: "It must be expensive." (cf. post-apocalyptic science fiction)

Given the many Asian peoples populating Los Angeles in A.D. 2019, and the cityspeak dialect policeman Gaff speaks to the Blade Runner, Rick Deckard, clearly indicates that much cultural mixing has happened. Globalization also is reflected in the name of the Shimago-Domínguez Corporation, whose slogan proclaims: "Helping America into the New World".[12] This indicates that a mass migration is occurring, as there is a status quo that people want to escape. When Sebastian remarks of his downtown building "No housing shortage around here...plenty of room for everybody", it mirrors the late twentieth century problems of white flight, and the resulting urban decay in western cities, but on a worldwide scale.

The cultural and religious mixing can also be verified at the scene where Deckard chases Zhora. In the streets, we can see people dressed traditionally as Jews, hare krishnas, as well as young boys dressed as punks.

Roy sparing Deckard's life

Some film critics believe Roy saved Deckard's life so that Deckard would continue to live with knowledge of Roy's experience—being about to die. In this manner, Roy prevents his death by passing on his experience. Furthermore, Roy ensures that Deckard will remember him for the rest of his life.[13][14]

Deckard: human or replicant?

There is a sequence added to the Director's Cut in which Deckard dreams about a unicorn; later, he finds an origami unicorn outside his apartment, left there by Gaff, suggesting that Gaff knows about Deckard's dream in the same manner that Deckard knows about Rachael's implanted memories. Even without considering this scene, there is other evidence that allows for the possibility of Deckard being a replicant, but does not eliminate the possibility of Deckard being human.

- The fact that Deckard's apartment is full of photographs, none of them recent or in color. Replicants have a taste for photographs, because it provides a tie to a non-existent past.[16]

- The scene in which Rachael asks Deckard whether he has passed the Voight-Kampff test himself, and receives no answer.[16]

- The fact that Gaff, who had shown no sympathy for Deckard throughout the film, tells him "You've done a man's job, sir!" after Roy expires, lets Rachael live and does not intervene when she and Deckard leave the apartment.[16]

Relevant opinions from those involved:

The purpose of this story as I saw it was that in his job of hunting and killing these replicants, Deckard becomes progressively dehumanized. At the same time, the replicants are being perceived as becoming more human. Finally, Deckard must question what he is doing, and really what is the essential difference between him and them? And, to take it one step further, who is he if there is no real difference?

Philip K. Dick[17]

- Philip K. Dick wrote the character Deckard as a human in the original novel.[18] The film differs from the book in some ways that provide ambiguity on the issue. For example, the book states explicitly that Deckard passed the Voight-Kampff test, while the movie shows Deckard declining to answer whether he did or not.

- Hampton Fancher has said that he wrote the character as a human, but wanted the film to suggest the possibility that he may be a replicant. When asked, "Is Deckard a replicant?", Fancher replied, "No. It wasn't like I had a tricky idea about Deckard that way."[19] During a discussion panel with Ridley Scott to discuss Blade Runner: The Final Cut, Fancher again stated that he believes Deckard is human (saying that "[Scott's] idea is too complex"), but also repeated that he prefers the film to remain ambiguous: "I like asking the question and I like it to be asked but I think it’s nonsense to answer it. That’s not interesting to me."[20]

- Harrison Ford considers Deckard to be human. "That was the main area of contention between Ridley and myself at the time," Ford told an interviewer during a BBC One Hollywood Greats segment. "I thought the audience deserved one human being on screen that they could establish an emotional relationship with. I thought I had won Ridley's agreement to that, but in fact I think he had a little reservation about that. I think he really wanted to have it both ways."[21]

- Ridley Scott stated in an interview in 2002 that he considers Deckard to be a replicant.[22][23] In a 2007 interview with Wired, he reiterated that he believes Deckard to unquestionably be a replicant and that he considers the debate to be closed. He also suggests that Ford may have since adopted this view as well.[24]

References

- ↑ "2019: Off-World Archives". Scribble.com. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- 1 2 3 Jenkins, Mary. (1997) The Dystopian World of Blade Runner: An Ecofeminist Perspective

- 1 2 "Blade Runner – FAQ". Faqs.org. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- ↑ Kerman, Judith. (1991) Retrofitting Blade Runner: Issues in Ridley Scott's "Blade Runner" and Philip K. Dick's "Do Android's Dream of Electric Sheep?" ISBN 978-0-87972-510-5

- ↑ Karantinos, Thomas. (2003) Eyes in Bladerunner

- ↑ Sammon, Paul M. (2000). "VIII: The Crew". Future Noir: THE MAKING OF Blade Runner.

- ↑ Gossman, Jean-Paul. (2001) Blade Runner - A Postmodernist View

- ↑ Newland, Dan. (1997) Christian Symbolism

- ↑ Pate, Anthony. (2009) Nietzsche's Ubermensch in the Hyperreal Flux: An Analysis of Blade Runner, Fight Club, and Miami Vice

- ↑ Card, Orson Scott (June 1989). "Light-years and Lasers / Science Fiction Inside Your Computer". Compute!. p. 29. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ↑ Leaver, Tama. (1997)'Post-Humanism and Ecocide in William Gibson's Neuromancer and Ridley Scott's Blade Runner'

- ↑ Välimäki, Teo. (1999) Comparing Philip K. Dick's Novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and Ridley Scott's Film Blade Runner in Terms of Internationalisation

- ↑ "The Top 5 Worst Lines of Dialogue (From Movies That Don't Actually Suck)" Wayne Gladstone, Cracked.com, August 8, 2007

- ↑ "Confused Matthew". Confused Matthew. 2012-05-18. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- ↑ Greenwald, Ted. "Q&A: Ridley Scott Has Finally Created the Blade Runner He Always Imagined". Wired.com. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- 1 2 3 Lacey, Nick (2000). York Film Notes: "Blade Runner". Harlow: Longman [u.a.] p. 29. ISBN 0-582-43198-0.

- ↑ "P.K. Dick Interview". Devo.com. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- ↑ Dick, Philip K. (1968). Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep. New York: Ballantine. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-56865-855-1.

- ↑ "Anderson, Jeffrey; "Hampton Fancher interview"". Ctv.es. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- ↑ 18Jun08. "Ridley Scott compares Blade Runner to little orphan annie". Darthmojo.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- ↑ Hollywood Greats – Edited clip from BBC1 documentary program.

- ↑ Video of Ridley Scott – Interview where he states that Deckard is a replicant

- ↑ BBC News article about Ridley Scott on Deckard being a replicant

- ↑ Greenwald, Ted. "Interview with Ridley Scott in Wired magazine". Wired.com. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

Further reading

- Telotte, J.P. (1999). A Distant Technology: Science Fiction Film and the Machine Age. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press. pp. 165, 180–185. ISBN 978-0-8195-6346-0.

- Menville, Douglas; R. Reginald (1985). Futurevisions: The New Golden Age of the Science Fiction Film. Van Nuys, CA: Newcastle. pp. 8, 15, 128–131, 188. ISBN 978-0-89370-681-4.

External links

- Blade Runner FAQ – Is Deckard a Replicant? (Archived)

- The Replicant Option – essay by Detonator (Archived)

- Deckard Is Not A Replicant – essay by Martin Connolly (Archived)

- "Blade Runner riddle solved". BBC News. 2000-07-09. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- Hampton Fancher interview

- Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? ISBN 978-0-345-40447-3