The Incredible Melting Man

| The Incredible Melting Man | |

|---|---|

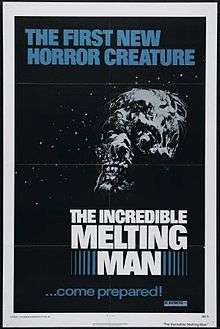

Theatrical release poster. | |

| Directed by | William Sachs |

| Produced by | Samuel W. Gelfman |

| Written by | William Sachs |

| Starring |

Alex Rebar Burr DeBenning Myron Healey |

| Music by | Arlon Ober |

| Cinematography | Willy Curtis |

| Edited by | James Beshears |

Production company |

Quartet Productions |

| Distributed by | |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 84 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The Incredible Melting Man is a 1977 American science fiction horror film about an astronaut whose body begins to melt after he is exposed to radiation during a space flight to Saturn, driving him to commit murders and consume human flesh to survive. It was written and directed by William Sachs, with scenes added and reshot during post-production by the producers without Sachs' participation. The film starred Alex Rebar as the main character, alongside Burr DeBenning as a scientist trying to help him and Myron Healey as a United States Air Force general seeking to capture him. While writing and shooting, Sachs was influenced by The Night of the Living Dead.[1] With the changes by the producers, the final film has been described as a remake of First Man into Space (1959),[2][3][4] which in turn was directly influenced by The Quatermass Xperiment, [5] even though Sachs had never seen either of those films.[6]

The screenplay which Sachs dramatized was originally intended as a parody of horror films, but comedic scenes were edited out during production and new horror scenes added. Sachs claimed that the producers decided during shooting that a straight horror film would be more financially successful, and that the film suffered as a result. The Incredible Melting Man was produced by American International Pictures, which also handled the theatrical distribution. The film includes several homages to science fiction and horror films of the 1950s. Makeup artist Rick Baker provided the gory makeup effects for the film. He originally created four distinct stages of makeup design so that the main character's body would appear to melt gradually, but the stages were ultimately cut from the final film.

The film was commercially successful, but it received largely negative reviews, although even critical reviews complimented Baker's makeup effects. According to writer/director Sachs, many scenes that were re-shot and changed by the producers proved problematic due to their inferior acting.[1] The Incredible Melting Man was featured in the comedy It Came from Hollywood (1982) and inspired the makeup effects for a scene in the science fiction-action film RoboCop (1987). It was also featured in a season 7 episode of the comedy television series Mystery Science Theater 3000.

Plot

During a space flight to Saturn, three astronauts are exposed to a blast of radiation which kills two of them and seriously injures the third, Colonel Steve West (Rebar). He is next shown unconscious in a hospital back on Earth, with bandages covering his face; his physician, Dr. Loring (Lisle Wilson), cannot explain what is happening to West or how he survived the blast. After the doctor leaves, West awakens and is horrified to find the flesh on his face and hands melting away. Hysterical, he attacks and kills a nurse (Bonnie Inch), then escapes the hospital in a panic. Loring and Dr. Theodore "Ted" Nelson (DeBenning), a scientist and friend of West, discover that the nurse's corpse is emitting feeble radiation, and realize West's body has become radioactive. Nelson believes West has gone insane, and concludes he must consume human flesh in order to slow the melting. Nelson calls General Michael Perry (Healey), a United States Air Force officer familiar with West's accident, and the general agrees to help Nelson find him.

West attacks and kills a fisherman in a wood, then encounters and frightens a little girl (Julie Drazen) there, but she escapes unharmed. Nelson tracks West by following his radiation trail with a geiger counter, but only finds his detached ear stuck to a tree branch. Perry arrives by plane, and is picked up by Nelson; shortly thereafter, they visit the crime scene where the fisherman's body was found. Sheriff Neil Blake (Michael Alldredge) suspects that Nelson knows something, but Nelson tells the sheriff nothing because Perry had earlier informed him that any information about West was classified. Later that night, Nelson returns home to his pregnant wife Judy(Ann Sweeny), who tells him that her elderly mother Helen (Dorothy Love) and Helen's boyfriend Harold (Edwin Max) are coming over for dinner. On their way, however, Helen and Harold are attacked by West in their car, and he kills them both.

When Blake finds the bodies, he calls Nelson, who comes out to identify them. After Blake angrily demands an explanation, Nelson reluctantly reveals West's condition. Nelson believes West is somehow getting stronger the more his body decomposes. Back at Nelson's house, West attacks and kills Perry, although Judy is not harmed. Nelson and Blake arrive just as West escapes. West then stumbles upon the home of a married couple (played by Jonathan Demme and Janus Blythe). West kills the man and attacks his wife, but she drives him away after chopping his arm off with a kitchen knife. Blake receives a call about the attack and takes Nelson with him to investigate. They follow West to a giant power plant, and then up several flights of outside stairways.

Blake tries to shoot West with a shotgun, but the blasts do not stop West, who throws the sheriff over the railing into power lines, killing him. West hits Nelson and knocks him over the railing, leaving the doctor hanging on the side. Nelson appeals to West, reminding him that they were friends, and West decides to pull Nelson to safety. Two armed security guards then arrive and, in a panic, fatally shoot Nelson as he tries to protect West. An infuriated West kills the security guards and stumbles away. After collapsing against the side of a building, he slowly melts completely away. The next morning, a janitor finds his gory remains and casually mops them into a garbage can. The film ends with a radio news report about another astronaut team being sent to Saturn.

Production

Writing

The Incredible Melting Man was written and directed by filmmaker William Sachs.[7] The idea for the film came to him when his mother, working in the office of a spray paint company, showed him "gooey stuff" which was used as a basis for spray paint and jokingly suggested that he should do a film featuring that material.[6] During writing, Sachs was influenced by The Night of the Living Dead and wanted to give the film a 1950s horror film feeling.[1] But the final film, with its structure changed by the producers in post-production, has been described by some sources – including the film magazine Cinefantastique and the 1995 book Cult Science Fiction Films – as a remake of First Man into Space (1959), another film about an astronaut who becomes a monster after an accident in space.[2][3][4] Science fiction film historian Gene Wright suggested that the final film was heavily influenced by The Quatermass Xperiment (1955), a British horror film about an astronaut who begins mutating into an alien organism after a spaceflight.[8] Sachs, however, had never seen either of those films, and his original screenplay had a very different structure. He had originally written the script for The Incredible Melting Man as a parody of horror films.[9] According to Michael Adams, a film reviewer who interviewed Sachs, this was the reason that the film mixed horror with comedic moments, such as when Steve West's detached ear gets stuck on a tree, and when a janitor sweeps West's melted body into a garbage can at the end of the film. Adams claims that this explains several comedic lines of dialogue otherwise inconsistent with the rest of the film, including one moment when homeless men notice the melting West and say to each other, "You think we've got trouble, look at that dude".[9] In Sachs' original version, the film opened with the wide-angle shot of the nurse running through the hallway; this would not have been in slow motion, unlike the final film, where the producers played it back slowed down. Only later would viewers have gradually learned the background of the melting man. All the scenes showing the astronauts in space and the lead character in the hospital were re-shot during post-production without influence by the director, and Sachs criticized both the acting in those scenes and how they restructure the film.[6] There are logical problems in the final film due to the re-shot scenes; it is never fully explained how West's spacecraft returned to Earth from Saturn when West himself was so seriously injured and the other two members of his crew were both killed.[10][11]

Welch D. Everman, author of Cult Science Fiction Films, pointed to several homages in the movie to science fiction and horror films of the 1950s.[2] The title itself is a reference to the Jack Arnold film The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), and the final scene when a radio report advertises another trip to Saturn, thus hinting that another accident could occur, was a common device in 1950s horror films. One difference, noted by Everman, is that in the 1950s films, government cover-ups and secret agendas were often ascribed to the good of the general public, whereas The Incredible Melting Man, like many late 1970s films of its genre, suggested otherwise.[2] Variety described the script, in addition to its horror elements, as "a human story attempting to leave a moral message as to whether society or the horrible creature it is chasing is really the most destructive".[10]

Casting

Alex Rebar starred as Steve West in one of only a handful of film appearances throughout his acting career.[12] Burr DeBenning played Dr. Ted Nelson,[13] and General Michael Perry was portrayed by Myron Healey, who was, Everman notes, often cast as a villain in 1950s science fiction films.[2] Film director Jonathan Demme played the small role of Matt Winters, one of West's victims.[13][14][15] Rainbeaux Smith, best known for her appearances in B movies and exploitation films, appeared in The Incredible Melting Man as a model who finds one of West's victims while trying to avoid a photographer seeking to take explicit photos of her.[13]

Filming

Producer Max Rosenberg, best known for his horror and supernatural films, provided the financing for The Incredible Melting Man.[13] Samuel W. Gelfman was the film's producer, and American International Pictures served as both the production company and the distributor.[16] According to Sachs, Gelfman and Rosenberg decided during shooting that a straight horror film would be more financially successful than a parody, so many of the comedic scenes were edited out and new horror scenes were shot and added to the film. Sachs said he felt the film was taken away from him, and that it suffered as a result because the producers tried to make it both a comedy and horror film, thus failing at both. Sachs said of the decision, "How can a serious horror movie end with the monster being shoveled into a garbage can?"[9]

Makeup artist Baker provided the special makeup effects for The Incredible Melting Man, which included the gradual melting of Steve West.[12][17] Rebar wore facial appliances that simulated melting flesh, and his hands and feet were fitted with liquid substances that dropped off as he walked, creating the appearance that West's body was falling apart.[2] During one scene, a murdered fisherman's severed head falls down a waterfall and smashes on the rocks below. To create the effect, Baker used a gelatin head with a wax skull and fake blood inside, which burst out upon impact.[18]

Baker created four distinct stages of makeup design so that West would appear to melt gradually as time passed. However, after the film went through two separate stages of editing, these makeup stages were ultimately eliminated from the final cut, and the character looks generally the same throughout the film.[19] Richard Meyers, author of The World of Fantasy Films, said actor Rebar was impatient and uncooperative with the extensive makeup sessions required for the effects, and thus did not wear all of the facial appliances Baker designed. This, Meyers said, might have been an additional factor in the lack of makeup effect stages in the final film.[20][21] The version of the film shot by Sachs had not included any scenes with West before he sustained the radiation poisoning that caused his body to melt. Such scenes were, however, re-shot later by the producers without Sachs' participation.[20][21]

Harry Woolman worked on the special effects along with Baker,[10] and Willy Curtis worked as the film's cinematographer.[13] Some scenes included photography errors, including one in which light shines through a kitchen window from outside even though it is supposed to be nighttime.[10][14] Michel Levesque provided art direction,[10] and the musical score was composed by London Philharmonic Orchestra conductor Arlon Ober.[22]

During post-production, as the producers decided to change the film into a more serious horror film, they filmed numerous scenes for that purpose without the participation of the director. Among those scenes is the entire prologue of the astronauts in space and West waking up in a hospital--these are the only scenes in which Rebar's face is seen without makeup. Additionally, the film was extensively re-edited by the producers. Sachs criticized the acting in those re-shot scenes, as well as the change of tone they bring into the film along with the re-editing by the producers.[6]

Release

Distribution

The distribution of The Incredible Melting Man was handled by American International Pictures,[16] with the involvement of film producer and distributor Irwin Yablans, who specialized primarily in B movies and low-budget horror films.[23] A trailer released for the film attempted to build tension by not revealing the monster right away. Instead, it showed portions of the scene immediately before the nurse is murdered, in which she runs down a hallway screaming and then crashes through a glass window trying to escape from West, who is only shown towards the end of the trailer.[24] In some advertisements, the monster from the film was described as "the first NEW horror creature".[25] As a promotional gimmick, candles were made and sold to advertise the film.[26]

One poster for the film included the statement: "Rick Baker, the new master of special effects, who brought you the magic of The Exorcist and gave you the wonder of King Kong, now brings you his greatest creation, The Incredible Melting Man". Although Baker assisted with the effects in The Exorcist (1973), Dick Smith was the makeup artist who primarily worked on that film, not Baker. Exorcist director William Friedkin was so angry about the poster that, upon seeing it on an associate's wall, he tore it down and ripped it to pieces. Baker, who did not know about the poster in advance, was horrified by the publicity campaign and publicly apologized for it, claiming: "Dick wanted some help so I first went out to do some work on the dummy whose head turns around 360 degrees. I really didn't do anything creative, I just did labor".[20]

Reception

The Incredible Melting Man is a singular theatrical experience that truly lives up to its crazed, pulpy title. Originally intended as an homage to the great "atomic age" horrors of the Fifties, William Sachs' clever satire was recut by its original distributor to cash in on the horror craze.— Chud.com, about The Incredible Melting Man[27]

The Incredible Melting Man received largely negative reviews, and has ranked among the Bottom 100 list of films on the Internet Movie Database,[28] although there have also been very favorable reviews.[29] The New York Post attested to Sachs' "simple mastery of the medium".[30] Tom Buckley of The New York Times described it as poorly written and directed, calling it one of many poor summer films released "to fill the need of drive-in operators for something cheap to put on the screen for the kids in the cars to ignore or laugh at".[7] The Globe and Mail writer Robert Martin praised Baker's makeup effects and said director Sachs did an efficient job building tension. However, Martin strongly criticized the script and the acting, claiming "logic and character are jettisoned in favor of suspense and horror," and said the film's positive elements were not strong enough to outweigh the negatives.[13] John Foyston of The Oregonian strongly condemned the film as gratuitously gory with thin, motiveless characters. He declared it worse than the horror film Manos: The Hands of Fate (1966), which is widely considered one of the worst films ever made.[31] Rick Worland, a film professor at the Meadows School of the Arts who wrote a book about horror films, said there was "little to recommend" about The Incredible Melting Man besides Baker's makeup effects.[32] Richard Meyers, a novelist who also wrote about science-fiction films, called the film muddled and dull: "Although the movie didn't have to be a sage examination of outer space diseases, it should at least have been exciting". Meyers complimented Baker's visual effects, but said his work was undermined by poor filming and actor Rebar's impatience with the makeup effects.[21]

A 1985 review in the book The Motion Picture Guide said, "The film tries to balance horror against morality but ends up shaky at best". The review described the special effects as "all right, but not nearly as gruesome as the film pretends they are".[14] In a review written shortly after the film was released, Variety wrote that the film "more often than not succeeds in telling a story and sustaining audience interest," and that the script included not only horrors, but also a human story with a moral message about society. However, the review also called the dialogue "trite," described some scenes as "technically incorrect," and said the film disappointed by lingering on the ordinary characters rather than on the monster.[10] Gene Wright, who wrote a book about science fiction films, said the film "attempts to blend pathos with awesome horror, but can't resist going for the gut with a surfeit of gore".[8] Blockbuster Inc.'s Guide to Movies and Videos gave the film 2.5 stars out of 4, and described the it as "unexciting and contrived, though Rick Baker's gross-out makeup is undeniably effective".[33] In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies, Phil Hardy described it as a better-than-average but "spotty" film, and said director William Sachs injected a sense of "grisly humor" into it. However, Hardy said the central concept inspired more laughter than terror, and called the special effects "only routine".[34]

Some reviews were more positive. Welch D. Everman, author of Cult Science Fiction Films, compared the relationship between West and Nelson to that of Victor Frankenstein and his monster in Mary Shelly's novel Frankenstein (1818). Everman wrote, "This is the kind of movie we've come to expect from AIP — cheaply made, nasty, and lots of fun".[11] John W. Bowen of the Belleville Intelligencer said he enjoyed the "camp" style of the film, adding, "It's both inexplicable and sad this brain-damaged yet fiercely determined little drive-in bottom feeder never garnered more than a tiny cult following over the years".[35] A 1978 critique in The Review of the News said, "Films like The Incredible Melting Man are not made to be good; they are made to be scary. For anyone looking to raise goosebumps on their flesh, this one is sufficient to give you your money's worth".[36] Matt Maiellaro, co-creator of the Cartoon Network series Aqua Teen Hunger Force, said the film inspired him to start making films himself,[37][38] adding, "When I was eight, I watched The Incredible Melting Man and knew that horror movies were going to be big religion in my life".[37] Z movie director Tim Ritter said he was partially inspired to enter show business by watching a trailer for The Incredible Melting Man at age 9.[39][40] Ritter said, "I was too young to see the movie, but the trailer really got into my imagination".[39]

Home release

The Incredible Melting Man was released on VHS in 1986 by Vestron Video,[41][42] and was rereleased in 1994 by Orion Pictures Library, although unlike other Orion VHS releases, it was not digitally remastered.[43][44] In September 2000, The Incredible Melting Man was once again released on VHS as part of "Midnite Movies", a line of B movies and exploitation films released to home video by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.[45][46] Although currently unavailable on DVD in Region 1, it was released in Region 2 by CMV Laservision on February 2, 2003.[47] In addition to the home video and DVD releases, The Incredible Melting Man has been featured in several film festivals, including the 1987 Visions Film Festival at the Enmore Theatre in Sydney, Australia;[48] the 2007 B-Fest in Chicago;[49] the 2008 Horrorama Movie Festival in Englewood, Colorado;[50] and the 2010 Groovy B-Movie Marathon in Durham, North Carolina.[51] Scream Factory released the film on Blu-ray in 2013.[52]

Cultural references

The film appeared in It Came from Hollywood, a 1982 comedy film featuring a compilation of clips from more than 100 B movies from the 1930s to the 1970s, which are shown between scripted segments performed by comedians.[53][54] Baker's effects from The Incredible Melting Man inspired the makeup effects for a scene in the science fiction-action film RoboCop (1987). During the scene, Emil Antonowsky (Paul McCrane) attempts to drive RoboCop off the road, but instead accidentally drives into a vat of toxic waste, causing the flesh to melt off his face and hands. These effects were conceived and designed by special makeup effects artist Rob Bottin, who was inspired by Baker's work on The Incredible Melting Man and dubbed the RoboCop effects "the Melting Man" as an homage to the production.[55]

The Incredible Melting Man was featured and lampooned in a Mystery Science Theater 3000 episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000. The film appeared in the fourth episode of the show's seventh season, which was broadcast on Comedy Central on February 24, 1996.[31][56] Michael J. Nelson, the show's head writer, spoke disparagingly about the film while describing it to the press: "The plot is – and I'm not kidding here – the plot is, a guy is melting. That's the plot".[56]

See also

- First Man into Space, a 1959 horror film with the same premise

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 "Torso Revue de Cinema: Interview with William Sachs (French)". Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Everman 1995, p. 103

- 1 2 DiFino, Nando (October 21, 1993). "Scary treats: Horror buff Nando DiFino shares his favorite cult films". The Post-Standard. p. H1.

- 1 2 Berg, Jon (1977). "Rick Baker". Cinefantastique. 6—7: 35.

- ↑ Hamilton, 2013, pp. 39--41.

- 1 2 3 4 William Sachs: Audio Commentary and interview on Blu-Ray-edition of "The Incredible Melting Man" by Arrow Video.

- 1 2 Buckley, Tom (May 4, 1978). "The Incredible Melting Man (1977)". The New York Times. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- 1 2 Wright 1983, p. 196

- 1 2 3 Adams 2010, pp. 27–28

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Variety's 1983, p. 378

- 1 2 Everman 1995, p. 102

- 1 2 Adams 2010, p. 27

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Martin, Robert (January 16, 1978). "Melted hands can't carry a film". The Globe and Mail.

- 1 2 3 Nash 1985, p. 1381

- ↑ Smith, Adam (April 26, 1998). "Altar'd states: Cult films from A to Z". Ottawa Citizen. p. D4.

- 1 2 Willis 1985, p. 201

- ↑ Beifuss, John (December 7, 2001). "Monster Maker: The Art and Soul of Rick Baker". The Commercial Appeal. p. E1.

- ↑ Harrington, Richard (November 2, 1980). "Bloody Illusions: The Cutting Edge of Gore". The Washington Post. p. M1.

- ↑ Meyers 1980, p. 90

- 1 2 3 Meyers 1980, p. 91

- 1 2 3 Meyers 1984, p. 42

- ↑ "Arlon Ober". Variety. January 17, 2005. p. 47.

- ↑ Martin, Robert (June 14, 1978). "Back on the beach without Frankie and Annette". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ Rhodes 2003, p. 48

- ↑ Meyers 1980, p. 89

- ↑ Jackson, Peter (March 30, 1999). "Tony signs up the starts to join his collection". The Journal. p. 28.

- ↑ "chud.com: About "The Incredible Melting Man".". Retrieved May 28, 2016..

- ↑ Adams 2010, pp. 26–27

- ↑ "VFTLA.org: Resume of William Sachs (PDF)" (PDF). Retrieved May 28, 2016..

- ↑ "VFTLA.org: Resume of William Sachs (PDF)" (PDF). Retrieved May 28, 2016..

- 1 2 Foyston, John (April 8, 1996). "MST3K: The show, the book, the major motion picture". The Oregonian. p. C01.

- ↑ Worland 2006, p. 108

- ↑ Blockbuster 1998, p. 590

- ↑ Hardy 1986, pp. 334–335

- ↑ Bowen, John W. (October 29, 2010). "Ten of the greatest bad horror films you probably haven't seen". Belleville Intelligencer. p. C1.

- ↑ "A Big Drip". The Review of the News. 14. 1978. p. 24.

- 1 2 Gonzalez, Isabel C. (October 26, 2009). "Connoisseurs of the Absurd". The New York Times. Retrieved December 26, 2010.

- ↑ Lewis, Sonja (August 19, 2004). "'Hunger Force' whets appetite of viewers". Pensacola News Journal. p. 1B.

- 1 2 Lindenmuth 1998, p. 27

- ↑ Crouch, Lori (July 25, 1994). "A midsummer night's scream; A Palm Beach county man takes a stab at horror films with the help of some local Shakespearean actors". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. p. 1D.

- ↑ "Circus musician who defected". The Courier-Mail. June 3, 1985.

- ↑ "'Ace of Spies' comes up trumps". Telegraph. July 5, 1985.

- ↑ "Sci-fi set features bargain prices". The Washington Times. May 12, 1994. p. M20.

- ↑ Harris, Christopher (June 3, 1994). "Video new releases". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ "Classic horrors 'Transparent Man,' 1970's 'Scream' join video ranks; Film noir 'Ghost Dog' tapped as week's best among new releases". The Washington Times. August 10, 2000. p. M24.

- ↑ McKay, John (December 5, 2000). "Eddie Murphy: Lotsa makeup and F/X are back in video, Nutty Professor II". Welland Tribune. p. A7.

- ↑ Bowen, John W. (October 29, 2010). "Ten of the greatest bad horror films you probably haven't seen yet". Belleville Intelligencer. p. C1.

- ↑ Kenny, Greg (May 22, 1987). "The Alien-ation of Enmore". Sydney Morning Herald. p. M2.

- ↑ "A Diary of B-Fest". Newstex. January 29, 2007.

- ↑ "Just follow our Go! guide to area haunted happenings". Dayton Daily News. October 10, 2008. p. GO16.

- ↑ "Hot tickets". The News & Observer. November 22, 2010. p. A1.

- ↑ Justin Edwards. "Scream Factory Adds THE INCREDIBLE MELTING MAN And THE VAMPIRE LOVERS To Their 2013 Slate!". Icons of Fright. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ↑ Willis 1995, p. 143

- ↑ Thomas, Bob (October 22, 1982). "Star Watch: The Preservation of Movie Schlock". Associated Press.

- ↑ Sammon, Paul M. (November 1987). "Shooting RoboCop". Cinefex (32): 39.

- 1 2 Baenen, Jeff (November 23, 1995). "Turkey Day will feature marathon of sci-fi turkeys". The Oregonian. p. F10.

Bibliography

- Adams, Michael (2010). Showgirls, Teen Wolves, and Astro Zombies: A Film Critic's Year-Long Quest to Find the Worst Movie Ever Made. It Books. ISBN 0-06-180629-3.

- Blockbuster Entertainment Guide to Movies and Videos 1999. Dell Publishing. 1998. ISBN 0-440-22598-1.

- Everman, Welch D. (1995). Cult Science Fiction Films: From the Amazing Colossal Man to Yog : The Monster from Space. Carol Publishing Corporation. ISBN 0-8065-1602-X.

- Hardy, Phil (1986). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies. Woodbury Press. ISBN 0-8300-0436-X.

- Lindenmuth, Kevin J. (1998). Making Movies on Your Own: Practical Talk from Independent Filmmakers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-0517-1.

- Meyers, Richard (1980). The World of Fantasy Films. A. S. Barnes & Company. ISBN 0-498-02213-7.

- Meyers, Richard (1984). S-F 2: A Pictorial History of Science Fiction Films from "Rollerball" to "Return of the Jedi". Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-0875-2.

- Nash, Jay Robert; Ross, Stanley Ralph (1985). The Motion Picture Guide: H-K. Cinebook. ISBN 0-933997-00-0.

- Parish, James Robert; Pitts, Michael R. (1990). The Great Science Fiction Pictures II. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-2247-4.}

- Rhodes, Gary Don (2003). Horror at the Drive-In: Essays in Popular Americana. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1342-5.

- Variety's Film Reviews: 1978–1980. R. R. Bowker. 1983. ISBN 0-8352-2795-2.

- Willis, Donald C. (1985). Variety's Complete Science Fiction Reviews. Garland. ISBN 0-8240-6263-9.

- Willis, Donald C. (1995). Horror and Science Fiction Films III. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-1723-3.

- Worland, Rick (2006). The Horror Film: An Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-3902-1.

- Wright, Gene (1983). The Science Fiction Image: The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Science Fiction in Film, Television, Radio and the Theater. New York City, New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-87196-527-5.

- Hamilton, John. The British Independent Horror Film, 1951-70. Hemlock Books, 2013. ISBN 978-1-903254-33-2.

External links