Stephen Duncan

| Stephen Duncan | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Stephen Duncan | |

| Born |

March 4, 1787 Carlisle, Pennsylvania |

| Died |

January 29, 1867 (aged 79) New York City |

| Resting place | Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia |

| Education | Dickinson College |

| Occupation | Plantation owner, banker |

| Known for | Wealthiest cotton planter in the South prior to the American Civil War; second largest slave owner in the country |

| Spouse(s) |

Margaret Ellis Catherine Bingaman (m. 1819) |

| Children |

(with Margaret): John Ellis Duncan, Sarah Jane Duncan (with Catherine): Stephen Duncan, Jr., Charlotte N. Duncan, M. L. Duncan, Henry P. Duncan |

Stephen Duncan (1787-1867) became a major planter and banker in Mississippi, migrating there from his home state of Pennsylvania after getting a medical degree. He became the wealthiest cotton planter in the South prior to the American Civil War, investing in railroads and Midwest lands. He owned thousands of acres of land and more than 1,000 slaves in the 1850s, cultivating both cotton and sugar cane as commodity crops.

In 1830 he and James Brown, a wealthy US Senator from Louisiana, paid for the purchase of land in Canada to aid American free blacks from Cincinnati found a new community, which became known as the Wilberforce Colony. In the 1830s, he was among the co-founders of the Mississippi Colonization Society in the 1830s, and helped purchase land in West Africa for removal of free people of color from the state.

.jpg)

In 1860 Duncan was the second-largest slave owner in the country. He opposed secession, incurring ostracism in Mississippi. He moved from Natchez to New York City in 1863, where he had long had business interests.

Early life

Stephen Duncan was born on March 4, 1787 in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.[1][2][3] He received a medical degree from Dickinson College.[1][4]

Antebellum career

In 1808, shortly before the War of 1812, Duncan moved as a young man to Natchez, Mississippi Territory, a developing river town that was important to trading along the Mississippi River.[1][2][4] In the antebellum South, Natchez became a thriving city thanks to the booming cotton industry. In Natchez, he became a banker and planter.[5][6][7] He served as the President of the Bank of Mississippi.[3]

Duncan purchased Auburn plantation from Lyman Harding in 1827.[1][3][8]

Duncan owned the following cotton and sugar plantations: L'Argent, Camperdown, Carlisle, Duncan, Duncannon, Duncansby, Ellisle, Homochitto, Middlesex, Oakley, Rescue, Reserve, Attakapas, and Saragossa.[2][6]

Duncan sold his crops through the merchant firm Washington, Jackson & Co. in New Orleans, instructing them to sell it through their subsidiary Todd, Jackson & Co. in Liverpool, England.[7] The revenue derived from the cotton and sugar sales was sent to Charles P. Leverich & Co., his bank headquartered in New York.[7] His plantations yielded returns of US$150,000 annually.[7] As a result of these financial transactions, Duncan became the richest cotton planter in the South before the American Civil War.[6] He reinvested his money in Northern railroad securities and in Midwestern public lands.[2]

In the 1850s, Duncan owned more than 1,000 slaves, making him the largest resident slave holder in Mississippi.[2][9] By 1860, Duncan's ownership of 858 slaves in Issaquena County made him second nationally to the estate of Joshua John Ward (1800-1853) of South Carolina, which controlled 1,130.[10]

Colonization efforts

In 1830, Duncan, along with planter James Brown, a former sugar planter, US Minister to France and US Senator from Louisiana, purchased 400 acres (1.6 km2) of land in the Huron Tract in Ontario, Canada, for a community of free American blacks. Quakers from Oberlin, Ohio had appealed to the wealthy planters to aid a group of emigrants from Cincinnati, Ohio.[11] The free people of color were fleeing discriminatory laws passed in Ohio and a violent race riot by whites in the summer of 1829; they developed the Wilberforce Colony.

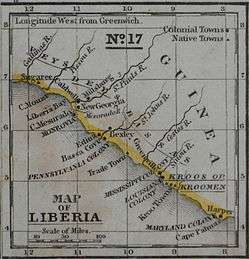

In the 1830s, together with major slave owners Isaac Ross (1760-1838), Edward McGehee (1786-1880), John Ker (1789-1850), and educator Jemeriah Chamberlain (1794-1851), president of Oakland College, Duncan co-founded the Mississippi Colonization Society. Their goal was to relocate (repatriate) free blacks and newly freed slaves to the developing colony of Liberia on the African continent.[12] The organization was modeled after the American Colonization Society, but it focused on freedmen from Mississippi. They bought a portion of land for the colony. Free blacks were thought to threaten the stability of slave societies, and Mississippi's population had a majority of slaves, outnumbering whites by a three-to-one ratio.[12]

Ross offered freedslaves in his will if they would relocate to Africa; after challenges, in the late 1840s about 300 of his slaves were relocated to Mississippi-in-Africa, as the colony was called. The Mississippi colony eventually became part of what developed as Liberia.

American Civil War and postbellum career

During the Civil War, Duncan opposed secession and the Confederate States Army.[1][2] As a result, he was ostracized by other Southerners.[3] With investments worth $1,060,000 unrelated to his plantations, he would be able to live comfortably regardless of the outcome of the war.[2] In 1863, Duncan left Natchez, moving to New York City.[1][2]

Personal life

Duncan married Margaret Ellis, and they had two children together, John Ellis and Sarah Jane Duncan. After his wife died, Duncan married again in 1819, to Catherine A. Bingaman. They had four children: Stephen, Jr.; Charlotte N., M. L., and Henry P. Duncan.[6]

Death

Duncan died on January 29, 1867, in New York City. He was buried in the Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In 1911, his heirs donated the Auburn mansion and its gardens to the city of Natchez.[1]

Legacy

- The Auburn mansion and grounds were designated as Duncan Memorial Park by the city of Natchez.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Natchez Guesthouse

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Engerman, Stanley L. (1976). Owens, Harry P., ed. The Southern Slave Economy. Perspectives and Irony in American Slavery. University Press of Mississippi. p. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 Alan Huffman, Mississippi in Africa: [the Saga of the Slaves of Prospect Hill Plantation and Their Legacy in Liberia Today, Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2010, pp. 91-92

- 1 2 David G. Sansing, Sim C. Callon, Carolyn Vance Smith, Natchez: An Illustrated History, Plantation Pub. Co., 1992, p. 88

- ↑ Ann Patton Malone, Sweet Chariot: Slave Family and Household Structure in Nineteenth-century Louisiana, Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1992, p. 287

- 1 2 3 4 Louisiana State University Library: Stephen Duncan Correspondence

- 1 2 3 4 Harold D. Woodman, King Cotton and His Retainers: Financing and Marketing the Cotton Crop of the South, 1800-1925, Beard Books, 199, p. 160

- ↑ William P. Baldwin, Elizabeth Turk, Mantelpieces of the Old South: Lost Architecture in Southern Culture, The History Press, 2005, p. 192

- ↑ 'Plantation Economy', American Cotton Planter, N. B. Cloud, 1854, Volume 2, p. 118

- ↑ Blake, Tom (2004). "The Sixteen Largest American Slaveholders from 1860 Slave Census Schedules". Ancestry.com.

- ↑ "THE WILBERFORCE SETTLEMENT 1830," Lucan, Waymarking.com. Accessed Jan. 22, 2014.

- 1 2 Mary Carol Miller, Lost Mansions of Mississippi, Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2010, Volume II, pp. 53-54

Further reading

- Martha Jane Brazy, An American Planter: Stephen Duncan of Antebellum Natchez And New York (Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 2006).

External links

- Stephen Duncan, FindAGrave