Steelyard

Coordinates: 51°30′41″N 0°05′26″W / 51.51139°N 0.09056°W

The Steelyard, from the Middle Low German Stalhof / Dutch Staalhof, was the main trading base (kontor) of the Hanseatic League in London during 15th and 16th centuries.

Location

The Steelyard was located on the north bank of the Thames by the outflow of the Walbrook, in the Dowgate ward of the City of London. The site is now covered by Cannon Street station and commemorated in the name of Steelyard Passage. The Steelyard, like other Hansa stations, was a separate walled community with its own warehouses on the river, its own weighing house, chapel, counting houses and residential quarters. In 1988 remains of the former Hanseatic trading house, once the largest medieval trading complex in Britain, were uncovered by archaeologists during maintenance work on Cannon Street Station.

As a church the Germans used former All-Hallows-the-Great, since there was only a small chapel on their own premises.

History

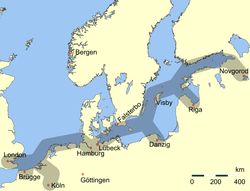

The first mention of a Hansa Almaniae (a "German Hansa") in English records is in 1282, concerning merely the community of the London trading post, only later to be made official as the Steelyard and confirmed in tax and customs concessions granted by Edward I, in a Carta Mercatoria ("merchant charter") of 1303. But the true power of the Hanse in English trade came much later, in the 15th century, as the German merchants, led by those of Cologne expanded their premises and extended their reach into the cloth-making industry of England. This led to constant friction over the legal position of English merchants in the Hanseatic towns and Hanseatic privileges in England, which repeatedly ended in acts of violence. Not only English wool but finished cloth was exported through the Hansa, who controlled the trade in Colchester and other cloth-making centres.[1] When the Steelyard was finally destroyed in 1469, the merchants of Cologne were exempted by Edward IV, which served to foment dissension among Hansards when the Hanse cities went to war with England, and Cologne was temporarily expelled from the League. But England, in the throes of the Wars of the Roses, was in a weak bargaining position, so despite several heavy defeats suffered by the Hanseatic fleet , the Hanseatic forces, consisting mainly of ships from only two cities (Lubeck and Gdansk), with the help of formidable ships like the Peter von Danzig won the Anglo-Hanseatic War and achieved a very favourable peace from the English commissioners in Utrecht in 1474.[2] In 1475 the Hanseatic League finally purchased the London site outright and it became universally known as the Steelyard, but this was the last outstanding success of the Hansa.[3] In exchange for the privileges the German merchants had to maintain Bishopsgate, one of the originally seven gates of the city, from where the roads led to their interests in Boston and Lynn.

Members of the Steelyard, normally stationed in London for only a few years, sat for a famous series of portraits by Hans Holbein the Younger in the 1530s, portraits which were so successful that the Steelyard Merchants commissioned from Holbein the allegorical paintings The Triumph of Riches and The Triumph of Poverty for their Hall. Both were destroyed by a fire, but there are copies in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. Later merchants of the Steelyard were portrayed by Cornelis Ketel. There is a fine description of the Steelyard by John Stow.

Later history

The prosperity of the Hanse merchants, who were in direct competition with those of the City of London, induced Queen Elizabeth to suppress the Steelyard and rescind its privileges in 1598. James I reopened the Steelyard, but it never again carried the weight it formerly had in London. Most of the buildings were destroyed during the Great Fire of London in 1666. The land and buildings remained the property of the Hanseatic League, and were subsequently let as warehouses to merchants. The Hanseatic League was never officially dissolved however; consulates of the Hanseatic League cities provided indirect communication between Northern Germany and Whitehall during the European blockade of the Napoleonic wars. Patrick Colquhoun was appointed as Resident Minister and Consul general by the Hanseatic cities of Hamburg in 1804 and by Bremen and Lübeck shortly after as the successor of Henry Heymann, who was also Stalhofmeister, "master of the Steelyard". Colquhoun was valuable to those cities through their occupation by the French since he provided indirect communication between Northern Germany and Whitehall,[4] especially in 1808, when the three cities considered their membership in the Confederation of the Rhine. His son James Colquhoun was his successor as Consul of the Hanseatic cities in London.

Lübeck, Bremen and Hamburg only sold their common property, the London Steelyard, to the South Eastern Railway in 1852.[5] Cannon Street station was built on the site and opened in 1866.

Steelyard balance

The Steelyard possibly gave its name to the steelyard balance, a type of portable balance, consisting of a suspended horizontal beam. An object to be weighed would be hung on the shorter end of the beam, while weights would be slid along the longer end, till the beam balanced. The weight could then be calculated by multiplying the sum of the known weights by the ratio of the distances from the beam's fulcrum.

References

- ↑ Medieval English urban history - Colchester

- ↑ F. R. Salter, "The Hanse, Cologne, and the Crisis of 1468" The Economic History Review 3.1 (January 1931), pp. 93-101.

- ↑ Prof. Rainer Postel, The Hanseatic League and its Decline

- ↑ G. D. Yeats, Biographical Sketch..., 44-45.

- ↑

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Steelyard, Merchants of the". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Steelyard, Merchants of the". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Prof. Rainer Postel, "The Hanseatic League and its decline" 1996

- Holbein portrait of Derich Born, 1533: one of the Steelyard portraits

- German Embassy; Hanseatic London, 26 September 2005

- Grant David Yeats, A Biographical Sketch of the Life and Writings of Patrick Colqhoun, London: G. Smeeton, 1818.