Sonnet 127

| Sonnet 127 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

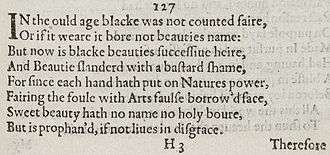

The first eight lines of Sonnet 127 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 127 of Shakespeare's sonnets (1609) is the first of the Dark Lady sequence (sonnets 127–152), called so because the poems make it clear that the speaker's mistress has black hair and eyes and dark skin.[2] In this poem the speaker finds himself attracted to a woman who is not beautiful in the conventional sense, and explains it by declaring that because of cosmetics one can no longer discern between true and false beauties, so that the true beauties have been denigrated and out of favour.[3]

Structure

Sonnet 127 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form abab cdcd efef gg and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 4th line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / And beauty slander'd with a bastard shame: (127.4)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

The first line contains two metrical variations: a mid-line reversal ("black was") and the rightward movement of the first ictus (resulting in a four-position figure, × × / /, sometimes referred to as a minor ionic):

× × / / / × × / × / In the old age black was not counted fair, (127.1)

Mid-line reversals also occur in lines 3 and 8, while initial reversals occur in lines 6, 9, 12, and potentially in line 2. A second minor ionic potentially occurs in line 10.

The meter demands that line 12's "slandering" function as two syllables.[4] Booth reads line 5's "pow'r" and line 7's "bow'r" as monosyllabic.[5]

Possible influences

Italian poet Francesco Petrarch, who was inspired by his love Laura, created the sonnet as a type of poetry. After his invention, the traditional Petrarchan theme became one of a "proud, virtuous lady and an abject, scorned lover".[6] The sonnet form became very popular and was introduced into English Poetry by Wyatt and Surrey. Yet, Shakespeare's sonnets vary dramatically from those of his contemporaries. His sonnets are "very different from Petrarch, in whose love poems the processing of tradition and the establishment of new voices are no less complex, but more systematically present, active, and profound."[7] There is also "relatively little of the platonic idealism that fills such works as Spenser's Amoretti in which the poet's love for his lady lifts him above human weakness to contemplation of the divine".[8]

Sonnet 127 reflects changing definitions of beauty in early modern England. Around the 1600s, makeup began to become available to everyone, thus being used by the masses and influencing Shakespeare's perception of beauty. The past in which "black was not counted fair" refers to traditional Elizabethan era priority of light skin, hair, and eyes over dark.[9]

Dark Lady

Many suggest Shakespeare was influenced to write the Dark Lady Sonnets by a person. However, attempts to locate the Dark Lady have failed. There is no consensus as to who the identity of the dark lady belongs to; the Sonnets give away nothing referring to age, background or station in life.[10]

The Dark Lady sonnets delve into sexuality, jealousy, and beauty.[11] The first sonnet of this series, Sonnet 127, begins with Shakespeare's Speaker apologizing for his mistress's un-ideal beauty, associated with old age.[12] Instead of shying away from unauthentic interpretation, he emphasizes his mistress's cruel and "black" state.[13] Some understand "black" to represent more than a color. Ronald Levao sees it as interchangeable with the term foul.[14]

The relationship between language and color is important for understanding the Dark Lady sonnets. Elizabeth Harvey explains: "The parallel between language and art was far from simple, and that rhetoric's colors depended upon a ghostly discourse of natural historical knowledge that invisibly shaped the chromatic lexicon of Shakespeare's sonnets."[15] The meanings and qualities associated with color are not necessarily universal or timeless, however. Recent critics have made arguments linking darkness with race and ethnicity. Scholars of early modern colonialism find it appropriate to portray the sexual relationship as a white man being sexually attracted to a black woman.[16]

The sonnet may also be understood as portraying an early reaction to women using cosmetics. The introduction of cosmetics should be viewed as a paradigm shift rather than a progression along the same spectrum. Margreta de Grazia reads Sonnet 127 in these terms: "Old values have been purged. Sweet beauty is stripped of her title (hath no name) and her sanctioned place (no holy boure), cast out into the contaminating open air (profaned) and thereby exposed to abuse and violation (in disgrace). In the place of 'beauties rose' now rules black."[17] Helen Vendler also examines this sonnet with an eye on cosmetics, "How did a black haired, black eyed woman come to be the reigning heir of beauty? The sonnet explains that the invention of cosmetics disgraced true beauty by allowing every ugly woman to become beautiful."[18] The speaker in sonnet 127 is therefore someone mourning the cheapness of cosmetic beauty but also recognizing that he finds himself to be attracted to a woman or women that use it.

References

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- ↑ Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets, Cambridge, London: Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 540.

- ↑ Vendler, pp. 540-1.

- ↑ Booth 2000, p. 111.

- ↑ Booth 2000, p. 108.

- ↑ Sonnets of Shakespeare. Masterplots, Fourth Edition [serial online]. November 2010;:1–4. Available from: MagillOnLiterature Plus, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- ↑ Lyne, Raphael. Shakespeare: Introduction: Tradition And The Sonnets. Vol. 5 Issue 3. Humanities International Complete, 2009. Print.

- ↑ Sonnets of Shakespeare. Masterplots, Fourth Edition [serial online]. November 2010;:1-4. Available from: MagillOnLiterature Plus, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- ↑ Dolan, Frances E. "Taking the Pencil out of God's Hand: Art, Nature, and the Face-Painting Debate in Early Modern England". Vol. 108 Issue 2. PMLA, 1993. Print.

- ↑ Green, Martin. "Emilia Lanier IS The Dark Lady Of The Sonnets." English Studies, Vol.87 Issue 5. MasterFILE Premier, 2006. Print.

- ↑ Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. USA: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data, 1997. Print.

- ↑ Edmonson, Paul and Stanley Wells. Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 2004. Print.

- ↑ Blackwell, Basil and Bateson, F. W.. Essays in Criticism. Vol. 2. MI: Michigan State College Press, 1952. Print.

- ↑ Levao, Ronald. "Something from Nothing in Shakespeare's Sonnets: Where Black is the Color, Where None is the Number." Literary Imagination, Vol. 12 Issue 3. New Brunswick, NJ: 2010. Print

- ↑ Harvey, Elizabeth and Schoenfeldt, Michael (ed). A Companion to Shakespeare's Sonnets. Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Print.

- ↑ Harvey, Elizabeth and Schoenfeldt, Michael (ed). A Companion to Shakespeare's Sonnets. Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Print.

- ↑ De, Grazia Margreta., and Stanley W. Wells. The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2001. Print.

- ↑ Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. USA: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data, 1997. Print.

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png)