Shockoe Bottom

|

Shockoe Valley and Tobacco Row Historic District | |

|

View north on 17th Street | |

| |

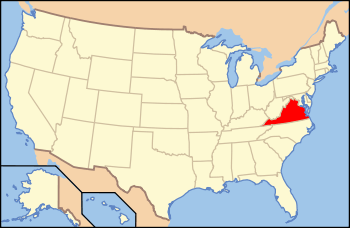

| Location | Roughly bounded by Dock, 15th, Clay, Franklin, and Pear Streets, Richmond, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°31′56″N 77°25′29″W / 37.53222°N 77.42472°WCoordinates: 37°31′56″N 77°25′29″W / 37.53222°N 77.42472°W |

| Area | 129 acres (52 ha) |

| Architectural style | Mid 19th Century Revival, Late 19th and 20th Century Revivals, Late Victorian |

| NRHP Reference # | 83003308 [1] |

| VLR # | 127-0344 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | February 24, 1983 |

| Designated VLR | July 21, 1981; August 23, 2007[2] |

Shockoe Bottom is an area in Richmond, Virginia, just east of downtown, along the James River. Located between Shockoe Hill and Church Hill, Shockoe Bottom contains much of the land included in Colonel William Mayo's 1737 plan of Richmond, making it one of the city's oldest neighborhoods.

History

Shockoe Bottom began developing in the late 18th century following the move of the state capital to Richmond, aided by the construction of Mayo's bridge across the James River (ultimately succeeded by the modern 14th Street Bridge), as well as the siting of key tobacco industry structures, such as the public warehouse, tobacco scales, and the Federal Customs House in or near the district.[3]

Throughout the 19th Century, Shockoe Bottom was the center of Richmond's commerce with ships pulling into port from the James River. Goods coming off these ships were warehoused and traded in Shockoe Valley.

Between the late 17th century and the end of the American Civil War in 1865, the area played a major role in the history of slavery in the United States, serving as the second largest slave trading center in the country, second to New Orleans. Profits from the trade in human beings fueled the creation of wealth for Southern whites and drove the economy in Richmond, leading 15th Street to be known as Wall Street in the antebellum period, with the surrounding blocks home to more than 69 slave dealers and auction houses.[4] In 2006, archaeological excavations were begun on the former site of Lumpkin's Jail.[5] Nearby is the African American Burial Ground, long used as a commercial parking lot, most recently by Virginia Commonwealth University, a state institution. It was reclaimed in 2011 after a decade-long community organizing campaign and today is a memorial park.

On the eve of the fall of Richmond to the Union Army in April 1865, evacuating Confederate forces were ordered to set fire to the city's tobacco warehouses. The fires spread, and completely destroyed Shockoe Slip and several other districts. The district was quickly rebuilt in the late 1860s, flourishing further in the 1870s, and forming much of its present historic building stock.[3] Architecturally, many of the buildings were constructed during the rebuilding following the Evacuation Fire of 1865, especially in a commercial variant of the Italianate style, including a 1909 fountain, dedicated to "one who loved animals." [6] The buildings in the district, which historically housed a variety of offices, wholesale and retail establishments, are now primarily restaurants, shops, offices, and apartments.[3] It warehoused many of the city's goods, mostly tobacco. The district began declining in the 1920s, as other areas of the city rose in prominence with the advent of the automobile. Numerous structures would be demolished and cleared, including (in the 1950s), the Tobacco Exchange, which had been at the heart of the district.[3] Up until they moved from Tobacco Row in the 1980s, the area was home to many of the country's largest tobacco companies.

Redevelopment

Shockoe Bottom became a major entertainment and arts district in the last two decades of the 20th century. One of the city's major art galleries, known as 1708, was positioned at 1708 East Main Street and named for its location. 1708 Gallery was followed by Artspace 1306 Gallery, which moved from 1306 East Cary Street in Shockoe Slip to just around the corner from 1708 at North 18th Street. Other galleries and studios were located in a massive old tobacco warehouse converted into the Tobacco Warehouse Arts Center. None of these galleries still exist in Shockoe Bottom. Artspace 1306 moved to Broad Street, changing its name simply to Artspace, and was followed by 1708 Gallery to Broad St., where 1708 remains in its second Broad Street location. From 6 East Broad, Artspace moved to Plant Zero, an arts complex south of the James River, and six of Artspace's founders and members remained at the 6 East Broad location to start Art6 Gallery. The owners and management of the Tobacco Warehouse Arts Center re-located to Petersburg, Virginia.

After centuries of periodic flooding by the James River, development was greatly stimulated by the completion of Richmond's James River Flood Wall and the Canal Walk in 1995. Ironically, the next flooding disaster came not from the river, but from Hurricane Gaston, which brought extensive local tributary flooding along the basin of Shockoe Creek and did extensive damage to the area in 2004, with businesses being shut down and many buildings condemned.

A major boom in residential growth was created in the mid-1990s when old warehouses in Tobacco Row were converted into apartments. Since then, more vacant buildings have been replaced with residential dwellings and new ones have been built.

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Shockoe Slip Historic District National Register Nomination – Boundary Increase" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ↑ Trammel, Jack (2012). The Richmond Slave Trade: The Economic Backbone of the Old Dominion. The History Press. ISBN 9781609494131.

- ↑ Laird, Matthew. "Preliminary Archaeological Investigation of the Lumpkin's Jail Site" (PDF). VCU Library. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ "Shockoe Slip". Historic Richmond Foundation.

External links

|

Court End | Upper Shockoe Valley | Union Hill |  |

| Capitol Hill | |

Church Hill | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Manchester Mayo Bridge over the James River |

Rockett's Landing |