Shemini (parsha)

Shemini, Sh'mini, or Shmini (שְּׁמִינִי — Hebrew for "eighth," the third word, and the first distinctive word, in the parashah) is the 26th weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the third in the Book of Leviticus. It constitutes Leviticus 9:1–11:47. The parashah is made up of 4,670 Hebrew letters, 1,238 Hebrew words, and 91 verses, and can occupy about 157 lines in a Torah Scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1]

Jews read it the 25th or 26th Sabbath after Simchat Torah, in late March or April.[2] In years when the first day of Passover falls on a Sabbath (as it does in 2015, 2016, 2018, and 2019), Jews in Israel and Reform Jews read the parashah following Passover one week before Conservative and Orthodox Jews in the Diaspora. In such years, Jews in Israel and Reform Jews celebrate Passover for seven days and thus read the next parashah (in 2015 and 2018, Shemini) on the Sabbath one week after the first day of Passover, while Conservative and Orthodox Jews in the Diaspora celebrate Passover for eight days and read the next parashah (in 2015 and 2018, Shemini) one week later. In some such years (for example, 2015 and 2018), the two calendars realign when Conservative and Orthodox Jews in the Diaspora read Behar together with Bechukotai while Jews in Israel and Reform Jews read them separately.[3]

Parashah Shemini tells of the consecration of the Tabernacle, the deaths of Nadab and Abihu, and the dietary laws of kashrut (כַּשְׁרוּת).

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot.[4]

First reading — Leviticus 9:1–16

In the first reading (עליה, aliyah), on the eighth day of the ceremony to ordain the priests and consecrate the Tabernacle, Moses instructed Aaron to assemble calves, rams, a goat, a lamb, an ox, and a meal offering as sacrifices (קָרְבֳּנוֹת, korbanot) to God, saying: "Today the Lord will appear to you."[5] They brought the sacrifices to the front of the Tent of Meeting, and the Israelites assembled there.[6] Aaron began offering the sacrifices as Moses had commanded.[7]

Second reading — Leviticus 9:17–23

In the second reading (עליה, aliyah), Aaron concluded offering the sacrifices as Moses had commanded.[8] Aaron lifted his hands toward the people and blessed them.[9] Moses and Aaron then went inside the Tent of Meeting, and when they came out, they blessed the people again.[10] Then the Presence of the Lord appeared to all the people.[10]

.jpg)

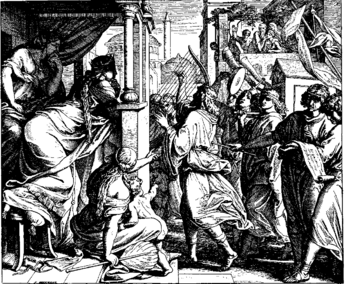

Third reading — Leviticus 9:24–10:11

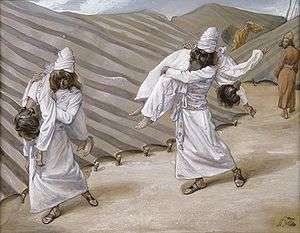

In the third reading (עליה, aliyah), fire came forth and consumed the sacrifices on the altar, and the people shouted and fell on their faces.[11] Acting on their own, Aaron's sons Nadab and Abihu each took his fire pan, laid incense on it, and offered alien fire, which God had not commanded.[12] And God sent fire to consume them, and they died.[13] Moses told Aaron, "This is what the Lord meant when He said: ‘Through those near to Me I show Myself holy, and gain glory before all the people,'" and Aaron remained silent.[14] Moses called Aaron's cousins Mishael and Elzaphan to carry away Nadab's and Abihu's bodies to a place outside the camp.[15] Moses instructed Aaron and his sons Eleazar and Ithamar not to mourn Nadab and Abihu by rending their garments or leaving their hair unshorn and not to go outside the Tent of Meeting.[16] And God told Aaron that he and his sons must not drink wine or other intoxicants when they entered the Tent of Meeting, so as to distinguish between the sacred and the profane.[17]

Fourth reading — Leviticus 10:12–15

In the fourth reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses directed Aaron, Eleazar, and Ithamar to eat the remaining meal offering beside the altar, designating it most holy and the priests' due.[18] And Moses told them that their families could eat the breast of the elevation offering and the thigh of the gift offering in any clean place.[19]

Fifth reading — Leviticus 10:16–20

In the fifth reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses inquired about the goat of sin offering, and was angry with Eleazar and Ithamar when he learned that it had already been burned and not eaten in the sacred area.[20] Aaron answered Moses: "See, this day they brought their sin offering and their burnt offering before the Lord, and such things have befallen me! Had I eaten sin offering today, would the Lord have approved?"[21] And when Moses heard this, he approved.[22]

Sixth reading — Leviticus 11:1–32

In the sixth reading (עליה, aliyah), God then instructed Moses and Aaron in the dietary laws of kashrut (כַּשְׁרוּת).[23]

Seventh reading — Leviticus 11:33–47

In the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), God instructed Moses and Aaron in several laws of purity, saying: "You shall be holy, for I am holy."[24]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[25]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013–2014, 2016–2017, 2019–2020 . . . | 2014–2015, 2017–2018, 2020–2021 . . . | 2015–2016, 2018–2019, 2021–2022 . . . | |

| Reading | 9:1–10:11 | 10:12–11:32 | 11:1–47 |

| 1 | 9:1–6 | 10:12–15 | 11:1–8 |

| 2 | 9:7–10 | 10:16–20 | 11:9–12 |

| 3 | 9:11–16 | 11:1–8 | 11:13–19 |

| 4 | 9:17–23 | 11:9–12 | 11:20–28 |

| 5 | 9:24–10:3 | 11:13–19 | 11:29–32 |

| 6 | 10:4–7 | 11:20–28 | 11:33–38 |

| 7 | 10:8–11 | 11:29–32 | 11:39–47 |

| Maftir | 10:8–11 | 11:29–32 | 11:45–47 |

In inner-Biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[26]

Leviticus chapters 8–9

This is the pattern of instruction and construction of the Tabernacle and its furnishings:

| Item | Instruction | Construction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Verses | Order | Verses | |

| The Sabbath | 16 | Exodus 31:12–17 | 1 | Exodus 35:1–3 |

| Contributions | 1 | Exodus 25:1–9 | 2 | Exodus 35:4–29 |

| Craftspeople | 15 | Exodus 31:1–11 | 3 | Exodus 35:30–36:7 |

| Tabernacle | 5 | Exodus 26:1–37 | 4 | Exodus 36:8–38 |

| Ark | 2 | Exodus 25:10–22 | 5 | Exodus 37:1–9 |

| Table | 3 | Exodus 25:23–30 | 6 | Exodus 37:10–16 |

| Menorah | 4 | Exodus 25:31–40 | 7 | Exodus 37:17–24 |

| Altar of Incense | 11 | Exodus 30:1–10 | 8 | Exodus 37:25–28 |

| Anointing Oil | 13 | Exodus 30:22–33 | 9 | Exodus 37:29 |

| Incense | 14 | Exodus 30:34–38 | 10 | Exodus 37:29 |

| Altar of Sacrifice | 6 | Exodus 27:1–8 | 11 | Exodus 38:1–7 |

| Laver | 12 | Exodus 30:17–21 | 12 | Exodus 38:8 |

| Tabernacle Court | 7 | Exodus 27:9–19 | 13 | Exodus 38:9–20 |

| Priestly Garments | 9 | Exodus 28:1–43 | 14 | Exodus 39:1–31 |

| Ordination Ritual | 10 | Exodus 29:1–46 | 15 | Leviticus 8:1–9:24 |

| Lamp | 8 | Exodus 27:20–21 | 16 | Numbers 8:1–4 |

.jpg)

Leviticus chapter 9

In Leviticus 9:23–24, the Presence of the Lord appeared to the people and fire came forth and consumed the sacrifices on the altar. God also showed approval by sending fire in Judges 13:15–21 upon the birth of Samson, in 2 Chronicles 7:1 upon the dedication of Solomon's Temple, and in 1 Kings 18:38 at Elijah's contest with the prophets of Baal.[27]

.jpg)

Leviticus chapter 10

Leviticus 10:1 reports that Nadab and Abihu put fire and incense (קְטֹרֶת, ketoret) in their censors and offered "strange fire" (אֵשׁ זָרָה, eish zarah). Exodus 30:9 prohibited offering "strange incense" (קְטֹרֶת זָרָה, ketoret zarah).

Leviticus 10:2 reports that Aaron’s sons Nadab and Abihu died prematurely, after Aaron had in Exodus 32:4 fashioned for the Israelites the Golden Calf and they said, “This is your god, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt.” Similarly, the northern Kingdom of Israel’s first King Jeroboam’s sons Nadab and Abijah died prematurely (Nadab in 1 Kings 15:28 and Abijah in 1 Kings 14:17), after Jeroboam had in 1 Kings 12:28 made two golden calves and said to the people, “This is your god, O Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt!” Professor James Kugel of Bar Ilan University noted that Abihu and Abijah are essentially the same names, as Abijah is a variant pronunciation of Abihu.[28]

Leviticus chapter 11

The Torah sets out the dietary laws of kashrut (כַּשְׁרוּת) in both Leviticus 11 and Deuteronomy 14:3–21. And the Hebrew Bible makes reference to clean and unclean animals in Genesis 7:2-9, Judges 13:4, and Ezekiel 4:14.

Leviticus 11:8 and 11 associate death with uncleanness. In the Hebrew Bible, uncleanness has a variety of associations. Leviticus 21:1–4, 11; and Numbers 6:6–7; and 19:11–16; also associate it with death. And perhaps similarly, Leviticus 12 associates it with childbirth and Leviticus 13–14 associates it with skin disease. Leviticus 15 associates it with various sexuality-related events. And Jeremiah 2:7, 23; 3:2; and 7:30; and Hosea 6:10 associate it with contact with the worship of alien gods.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[29]

Leviticus chapter 10

Philo interpreted Leviticus 10 to teach that because Nadab and Abihu fearlessly and fervently proceeded rapidly to the altar, an imperishable light dissolved them into ethereal beams like a whole burnt-offering and took them up to heaven.[30] Thus, Nadab and Abihu died in order that they might live, exchanging their mortal lives for immortal existence, departing from the creation to the creator God. Philo interpreted the words of Leviticus 10:2, "they died before the Lord," to celebrate their incorruptibility and demonstrate that they lived, for no dead person could come into the sight of the Lord.[31]

Josephus taught that Nadab and Abihu did not bring the sacrifices that Moses told them bring, but rather brought those that they used to offer before, and consequently they were burned to death.[32]

Leviticus chapter 11

Aristeas cited as a reason for dietary laws that they distinctly set Jews apart from other people.[33]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[34]

Leviticus chapter 9

Rabbi Judah taught that the words of Leviticus 9:1, "And it came to pass on the eighth day," begin the second major topic of the book of Leviticus.[35]

Rabbi Levi (or others say Rabbi Jonathan) taught that a tradition was handed down from the Men of the Great Assembly that wherever Scripture uses the term "and it was" or "and it came to pass" (וַיְהִי, va-yehi), it indicates the approach of trouble (as וַיְהִי, va-yehi can be read as וַיי, הִי, vai, hi, "woe, sorrow"). Thus, the first words of Leviticus 9:1, "And it came to pass (וַיְהִי, va-yehi) on the eighth day," presage that Nadab and Abihu died on that day.[36]

But a Baraita compared the day that the Israelites dedicated the Tabernacle with the day that God created the universe. Reading the words of Leviticus 9:1, "And it came to pass on the eighth day," a Baraita taught that on that day (when the Israelites dedicated the Tabernacle) there was joy before God as on the day when God created heaven and earth. For Leviticus 9:1 says, "And it came to pass (וַיְהִי, va-yehi) on the eighth day," and Genesis 1:5 says, "And there was (וַיְהִי, va-yehi) one day."[36]

Rabbi Eliezer interpreted the words, "And there I will meet with the children of Israel; and [the Tabernacle] shall be sanctified by My glory," in Exodus 29:43 to mean that God would in the future meet the Israelites and be sanctified among them. The Midrash reports that this occurred on the eighth day of the consecration of the Tabernacle, as reported in Leviticus 9:1. And as Leviticus 9:24 reports, "when all the people saw, they shouted, and fell on their faces."[37]

Rabbi Helbo taught that after ministering in the office of High Priest for the seven days of consecration, Moses imagined that the office was his, but on the eighth day (as indicated by Leviticus 9:1) God told Moses that the office belonged not to Moses but to his brother Aaron.[38]

A Baraita taught that in the inauguration of the Tabernacle, Aaron removed himself for seven days and then officiated for one day. Throughout the seven days, Moses transmitted to Aaron the Torah's guidelines to train Aaron in the service. Following this example, in subsequent generations, the High Priest removed himself for seven days before Yom Kippur to officiate for one day. And two scholars of the disciples of Moses (thus excluding the Sadducees) transmitted the Torah's guidelines to the High Priest throughout the seven days to train him in the service.[39]

Rabbi Jacob bar Acha taught in the name of Rabbi Zorah that the command to Aaron in Leviticus 8:35, "at the door of the tent of meeting shall you abide day and night seven days, and keep the charge of the Lord," served as a source for the law of seven days of mourning for the death of a relative (שִׁבְעָה, shivah). Rabbi Jacob bar Acha interpreted Moses to tell Aaron that just as God observed seven days of mourning for the then-upcoming destruction of the world at the time of the Flood of Noah, so too Aaron would observe seven days of mourning for the upcoming death of his sons Nadab and Abihu. And we know that God observed seven days of mourning for the destruction of the world by the Flood from Genesis 7:10, which says, "And it came to pass after the seven days, that the waters of the Flood were upon the earth." The Gemara asked whether one mourns before a death, as Jacob bar Acha appears to argue happened in these two cases. In reply, the Gemara distinguished between the mourning of God and people: People, who do not know what will happen until it happens, do not mourn until the deceased dies. But God, who knows what will happen in the future, mourned for the world before its destruction. The Gemara noted, however, that there are those who say that the seven days before the Flood were days of mourning for Methuselah (who died just before the Flood).[40]

Similarly, reading in Leviticus 9:1 that "it came to pass on the eighth day," a Midrash recounted how Moses told Aaron in Leviticus 8:33, "you shall not go out from the door of the tent of meeting seven days." The Midrash interpreted this to mean that Moses thereby told Aaron and his sons to observe the laws of mourning for seven days, before those laws would affect them. Moses told them in Leviticus 8:35 that they were to "keep the charge of the Lord," for so God had kept seven days of mourning before God brought the Flood, as Genesis 7:10 reports, "And it came to pass after the seven days, that the waters of the Flood were upon the earth." The Midrash deduced that God was mourning by noting that Genesis 6:6 reports, "And it repented the Lord that He had made man on the earth, and it grieved Him (וַיִּתְעַצֵּב, vayitatzeiv) at His heart." And 2 Samuel 19:3 uses the same word to express mourning when it says, "The king grieves (נֶעֱצַב, ne'etzav) for his son." After God told Moses in Exodus 29:43, "And there I will meet with the children of Israel; and [the Tabernacle] shall be sanctified by My glory," Moses administered the service for seven days in fear, fearing that God would strike him down. And it was for that reason that Moses told Aaron to observe the laws of mourning. When Aaron asked Moses why, Moses replied (in the words of Leviticus 8:35) "so I am commanded." Then, as reported in Leviticus 10:2, God struck Nadab and Abihu instead. And thus in Leviticus 10:3, Moses told Aaron that he finally understood, "This is what the Lord meant when He said: ‘Through those near to Me I show Myself holy, and gain glory before all the people.'"[41]

Rav Assi of Hozna'ah deduced from the words, "And it came to pass in the first month of the second year, on the first day of the month," in Exodus 40:17 that the Tabernacle was erected on the first of Nisan. With reference to this, a Tanna taught that the first of Nisan took ten crowns of distinction by virtue of the ten momentous events that occurred on that day.[42] The first of Nisan was: (1) the first day of the Creation,[43] (2) the first day of the princes' offerings,[44] (3) the first day for the priesthood to make the sacrificial offerings,[45] (4) the first day for public sacrifice, (5) the first day for the descent of fire from Heaven,[46] (6) the first for the priests' eating of sacred food in the sacred area, (7) the first for the dwelling of the Shechinah in Israel,[47] (8) the first for the Priestly Blessing of Israel,[48] (9) the first for the prohibition of the high places,[49] and (10) the first of the months of the year.[50]

Rabbi Tanhum taught in the name of Rabbi Judan that the words "for today the Lord appears to you" in Leviticus 9:4 indicated that God's presence, the Shekhinah, did not come to abide in the Tabernacle all the seven days of consecration when Moses ministered in the office of High Priest, but the Shekhinah appeared when Aaron put on the High Priest's robes.[51]

Reading the words of Leviticus 9:4, "And [take] an ox and a ram for peace-offerings . . . for today the Lord will appear to you," Rabbi Levi taught that God reasoned that if God would thus reveal God's Self to and bless him who sacrificed an ox and a ram for God's sake, how much more should God reveal God's Self to Abraham, who circumcised himself for God's sake. Consequently, Genesis 18:1 reports, "And the Lord appeared to him [Abraham]."[52]

Reading Leviticus 9:23, "And Moses and Aaron went into the tent of meeting," the Sifra asked why Moses and Aaron went into the Tabernacle together. The Sifra taught that they did so that Moses might teach Aaron the right of offering the incense.[53]

Rabbi Judah taught that the same fire that descended from heaven settled on the earth, and did not again return to its former place in heaven, but it entered the Tabernacle. That fire came forth and devoured all the offerings that the Israelites brought in the wilderness, as Leviticus 9:24 does not say, "And there descended fire from heaven," but "And there came forth fire from before the Lord." This was the same fire that came forth and consumed the sons of Aaron, as Leviticus 10:2 says, "And there came forth fire from before the Lord." And that same fire came forth and consumed the company of Korah, as Numbers 16:35 says, "And fire came forth from the Lord." And the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that no person departs from this world until some of that fire, which rested among humanity, passes over that person, as Numbers 11:2 says, "And the fire rested."[54]

.jpg)

Leviticus chapter 10

According to the Sifra, Nadab and Abihu took their offering in Leviticus 10:1 in joy, for when they saw the new fire come from God, they went to add one act of love to another act of life.[55]

A Midrash noted that Scripture records the death of Nadab and Abihu in numerous places.[56] This teaches that God grieved for Nadab and Abihu, for they were dear to God. And thus Leviticus 10:3 quotes God to say: "Through them who are near to Me I will be sanctified."[57]

A Midrash taught that the strange fire was neither from the continual offering of the evening nor from the continual offering of the morning, but was ordinary secular fire.[57] Similarly, Rabbi Akiva taught that the fire they brought was the kind used in a double stove, and read Leviticus 10:1 to report that they "offered unholy fire before the Lord."[58]

.jpg)

The Gemara presented alternative views of how the fire devoured Nadab and Abihu in Leviticus 10:2. According to one view, their bodies were not burned because Leviticus 10:2 says, "they died before the Lord," teaching that it was like normal death (from within, without an outward effect on their body). And according to the other view, they were actually burned. The fire commenced from within, as in normal death (and then consumed their bodies).[59]

Abba Jose ben Dosetai taught that Nadab and Abihu died in Leviticus 10:2 when two streams of fire came forth from the Holy of Holies and divided into four streams, of which two flowed into the nose of one and two into the nose of the other, so that their breath was burned up, but their garments remained untouched (as implied in Leviticus 10:5).[60]

Bar Kappara said in the name of Rabbi Jeremiah ben Eleazar that Nadab and Abihu died (as reported in Leviticus 10:2) because of four things: (1) for drawing too near to the holy place, (2) for offering a sacrifice that they had not been commanded to offer, (3) for the strange fire that they brought in from the kitchen, and (4) for not having taken counsel from each other, as Leviticus 10:1 says "Each of them his censer," implying that each acted on his own initiative.[61]

Similarly, reading the words of Leviticus 16:1, "the death of the two sons of Aaron, when they drew near before the Lord, and died," Rabbi Jose deduced that Aaron's sons died because they drew near to enter the Holy of Holies.[57]

Rabbi Mani of She'ab (in Galilee), Rabbi Joshua of Siknin (also in Galilee), and Rabbi Johanan all said in the name of Rabbi Levi that Nadab and Abihu died because of four things, in connection with each of which Scripture mentions death: (1) Because they had drunk wine, for in connection with drinking wine Leviticus 10:9 mentions death, saying, "Drink no wine nor strong drink . . . so that you do not die." (2) Because they lacked the prescribed number of garments (while officiating), for in connection with appropriate garments Exodus 28:43 mentions death, saying, "And they [the garments] shall be upon Aaron, and upon his sons . . . so that they bear no iniquity and die." Nadab and Abihu lacked their robes (implied perhaps by the report of Leviticus 10:5 that they their bodies were carried out in their tunics), in connection with which Exodus 28:35 mentions death, saying, "And it shall be upon Aaron to minister . . . so that he does not die." (3) Because they entered the Sanctuary without washing their hands and feet, for Exodus 30:21 says, "So they shall wash their hands and their feet, so that they do not die," and Exodus 30:20 says, "When they go into the tent of meeting, they shall wash with water, so that they do not die." (4) Because they had no children, for in connection with not having children Numbers 3:4 mentions death, saying, "And Nadab and Abihu died . . . and they had no children." Abba Hanin taught that it was because they had no wives, for Leviticus 16:6 says, "And [the High Priest shall] make atonement for himself, and for his house," and "his house" implies that he had to have a wife.[62]

Similarly, Rabbi Levi taught that Nadab and Abihu died because they were arrogant. Many women remained unmarried waiting for them. Nadab and Abihu thought that because their father's brother (Moses) was king, their mother's brother (Nachshon ben Aminadav) was a prince, their father (Aaron) was High Priest, and they were both Deputy High Priests, that no woman was worthy of them. Thus Rabbi Menahma taught in the name of Rabbi Joshua ben Nehemiah that Psalm 78:63 applied to Nadab and Abihu when it says, "Fire devoured their young men," because (as the verse continues), "their virgins had no marriage-song."[63]

Rabbi Eliezer (or some say Rabbi Eliezer ben Jacob) taught that Nadab and Abihu died only because they gave a legal decision in the presence of their Master Moses. Even though Leviticus 9:24 reports that "fire came forth from before the Lord and consumed the burnt-offering and the fat on the altar," Nadab and Abihu deduced from the command of Leviticus 1:7 that "the sons of Aaron the priest shall put fire upon the altar" that the priests still had a religious duty to bring some ordinary fire to the altar, as well.[64]

According to the Sifra, some say that Nadab and Abihu died because earlier, when at Sinai they were walking behind Moses and Aaron, they remarked to each other how in a little while, the two old men would die, and they would head the congregation. And God said that we would see who would bury whom.[65]

A Midrash taught that when Nadab, Abihu, and the 70 elders ate and drank in God's Presence in Exodus 24:11, they sealed their death warrant. The Midrash asked why in Numbers 11:16, God directed Moses to gather 70 elders of Israel, when Exodus 29:9 reported that there already were 70 elders of Israel. The Midrash deduced that when in Numbers 11:1, the people murmured, speaking evil, and God sent fire to devour part of the camp, all those earlier 70 elders had been burned up. The Midrash continued that the earlier 70 elders were consumed like Nadab and Abihu, because they too acted frivolously when (as reported in Exodus 24:11) they beheld God and inappropriately ate and drank. The Midrash taught that Nadab, Abihu, and the 70 elders deserved to die then, but because God so loved giving the Torah, God did not wish to create disturb that time.[66]

A Midrash taught that the death of Nadab and Abihu demonstrated the teaching of Rabbi Joshua ben Levi that prayer effects half atonement. At first (after the incident of the Golden Calf), God pronounced a decree against Aaron, as Deuteronomy 9:20 says, "The Lord was very angry with Aaron to have destroyed (לְהַשְׁמִיד , le-hashmid) him." And Rabbi Joshua of Siknin taught in the name of Rabbi Levi that "destruction" (הַשְׁמָדָה, hashmadah) means extinction of offspring, as in Amos 2:9, which says, "And I destroyed ( וָאַשְׁמִיד, va-ashmid) his fruit from above, and his roots from beneath." When Moses prayed on Aaron's behalf, God annulled half the decree; two sons died, and two remained. Thus Leviticus 8:1–2 says, "And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying: ‘Take Aaron and his sons'" (implying that they were to be saved from death).[67]

The Gemara interpreted the report in Exodus 29:43 that the Tabernacle "shall be sanctified by My glory" to refer to the death of Nadab and Abihu. The Gemara taught that one should read not "My glory" (bi-khevodi) but "My honored ones" (bi-khevuday). The Gemara thus taught that God told Moses in Exodus 29:43 that God would sanctify the Tabernacle through the death of Nadab and Abihu, but Moses did not comprehend God's meaning until Nadab and Abihu died in Leviticus 10:2. When Aaron's sons died, Moses told Aaron in Leviticus 10:3 that Aaron's sons died only so that God's glory might be sanctified through them. When Aaron thus perceived that his sons were God's honored ones, Aaron was silent, as Leviticus 10:3 reports, "And Aaron held his peace," and Aaron was rewarded for his silence.[68]

Similarly, a Midrash interpreted Leviticus 10:3, where Moses told Aaron, "This is what the Lord meant when He said: ‘Through those near to Me I show Myself holy, and gain glory before all the people.'" The Midrash taught that God told this to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai, when in Exodus 29:43 God said, "there I will meet with the children of Israel; and the Tabernacle shall be sanctified by My glory." And after the death of Nadab and Abihu, Moses said to Aaron, "At the time that God told me, I thought that either you or I would be stricken, but now I know that they [Nadab and Abihu] are greater than you or me."[69]

Similarly, the Sifra taught that Moses sought to comfort Aaron, telling him that at Sinai, God told him that God would sanctify God's house through a great man. Moses had supposed that it would be either through Aaron or himself that the house would be sanctified. But Moses said that it turned out that Aaron's sons were greater and Moses and Aaron, for through them had the house been sanctified.[70]

Rabbi Akiva taught that because Aaron's cousins Mishael and Elzaphan attended to the remains of Nadab and Abihu (as reported in Leviticus 10:4–5), they became the "certain men" who Numbers 9:6 reported "were unclean by the dead body of a man, so that they could not keep the Passover." But Rabbi Isaac replied that Mishael and Elzaphan could have cleansed themselves before the Passover.[71]

| Kohath | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amram | Izhar | Hebron | Uzziel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miriam | Aaron | Moses | Mishael | Elzaphan | Sithri | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nadab | Abihu | Eleazar | Ithamar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Family tree from Exodus 6:16–23)

.jpg)

The Tosefta found in the account of Leviticus 10:5 that Mishael and Elzaphan "carried them in their tunics out of the camp" that even when God is angry at the righteous, God is mindful of their honor. And the Tosefta concluded that if when God is angry at the righteous, their treatment is such, then when God is disposed to be merciful, how much more so will God be mindful of their honor.[72]

Our Rabbis taught in a Baraita that when Rabbi Ishmael's sons died, Rabbi Tarfon consoled him by noting that, as Leviticus 10:6 reports, upon the death of Nadab and Abihu, Moses ordered that "the whole house of Israel bewail the burning that the Lord has kindled." Rabbi Tarfon noted that Nadab and Abihu had performed only one good deed, as Leviticus 9:9 reports, "And the sons of Aaron presented the blood to him" (during the inaugural service of the Tabernacle). Rabbi Tarfon argued that if the Israelites universally mourned Nadab and Abihu, how much more was mourning due to Rabbi Ishmael's sons (who performed many good deeds).[73]

Rabbi Simeon taught that Nadab and Abihu died only because they entered the Tent of Meeting drunk with wine. Rabbi Phinehas in the name of Rabbi Levi compared this conclusion to the case of a king who had a faithful attendant. When the king found the attendant standing at tavern entrances, the king beheaded the attendant and appointed another in his place. The king did not say why he killed the first attendant, except that he told the second attendant not to enter the doorway of taverns, and thus the king indicated that he put the first attendant to death for such a reason. And thus God's command to Aaron in Leviticus 10:9 to "drink no wine nor strong drink" indicates that Nadab and Abihu died precisely because of wine.[74]

Rabbi Levi taught that God gave the section of the Torah dealing with the drinking of wine by priests, in Leviticus 10:8–11, on the day that the Israelites set up the Tabernacle. Rabbi Rabbi Johanan said in the name of Rabbi Bana'ah that the Torah was transmitted in separate scrolls, as Psalm 40:8 says, "Then said I, 'Lo I am come, in the roll of the book it is written of me.'" Rabbi Simeon ben Lakish (Resh Lakish), however, said that the Torah was transmitted in its entirety, as Deuteronomy 31:26, "Take this book of the law." The Gemara reported that Rabbi Johanan interpreted Deuteronomy 31:26, "Take this book of the law," to refer to the time after the Torah had been joined together from its several parts. And the Gemara suggested that Resh Lakish interpreted Psalm 40:8, "in a roll of the book written of me," to indicate that the whole Torah is called a "roll," as Zechariah 5:2 says, "And he said to me, 'What do you see?' And I answered, 'I see a flying roll.'" Or perhaps, the Gemara suggested, it is called "roll" for the reason given by Rabbi Levi, who said that God gave eight sections of the Torah, which Moses then wrote on separate rolls, on the day on which the Tabernacle was set up. They were: the section of the priests in Leviticus 21, the section of the Levites in Numbers 8:5–26 (as the Levites were required for the service of song on that day), the section of the unclean (who would be required to keep the Passover in the second month) in Numbers 9:1–14, the section of the sending of the unclean out of the camp (which also had to take place before the Tabernacle was set up) in Numbers 5:1–4, the section of Leviticus 16:1–34 (dealing with Yom Kippur, which Leviticus 16:1 states was transmitted immediately after the death of Aaron's two sons), the section dealing with the drinking of wine by priests in Leviticus 10:8–11, the section of the lights of the menorah in Numbers 8:1–4, and the section of the red heifer in Numbers 19 (which came into force as soon as the Tabernacle was set up).[75]

The Gemara read the term "strong drink" (שֵׁכָר, sheichar) in Leviticus 10:9 to mean something that intoxicates. And the Gemara cited a Baraita that taught that if a priest ate preserved figs from Keilah, or drank honey or milk (and thereby became disoriented), and then entered the Sanctuary (to perform the service), he was culpable.[76]

And the Gemara explained that the Sages ruled that Kohanim did not recite the Priestly Blessing at Minchah and Ne'ilah prayer services out of concern that some of the Kohanim might be drunk at that time of day (and Leviticus 10:9 prohibited Kohanim from participating in services when intoxicated). But the Kohanim did say the Priestly Blessing at Minchah and Ne'ilah services on Yom Kippur and other fast days, because the Kohanim would not drink on those days. Rabbi Isaac noted that Deuteronomy 10:8 speaks of separating the Levites "to minister to [God] and to bless in [God's] name" (and thus likens sacrificial service to blessing). From this, Rabbi Isaac deduced that as Leviticus 10:9 did not prohibit an officiating priest from eating the shells of grapes, a priest about to recite the Priestly Blessing could also eat the shells of grapes.[77]

A Baraita taught that both priests who were drunk with wine and those who let their hair grow long were liable to death. For Leviticus 10:9 says, "Drink no wine nor strong drink, you nor your sons with you, that you not die." And Ezekiel 44:20–21 juxtaposes the prohibition of long hair with that of drunkenness. Thus, the Baraita concluded that just as a priest's drunkenness during service was punishable by death, so was his growing long hair.[78] Thus, a Baraita taught that a common priest had to get his hair cut every 30 days, the High Priest every week on the eve of the Sabbath, and the king every day.[79]

A Baraita taught that the righteous are blessed, for not only do they acquire merit, but they bestow merit on their children and children's children to the end of all generations. The Baraita deduced from the words "that were left" used in Leviticus 10:12 to describe Aaron's remaining sons that those sons deserved to be burned like Nadab and Abihu, but Aaron's merit helped them avoid that fate.[80]

A Baraita reported that Rabbi taught that in conferring an honor, we start with the most important person, while in conferring a curse, we start with the least important. Leviticus 10:12 demonstrates that in conferring an honor, we start with the most important person, for when Moses instructed Aaron, Eleazar, and Ithamar that they should not conduct themselves as mourners, Moses spoke first to Aaron and only thereafter to Aaron's sons Eleazar and Ithamar. And Genesis 3:14–19 demonstrates that in conferring a curse, we start with the least important, for God cursed the serpent first, and only thereafter cursed Eve and then Adam.[81]

The Mishnah deduced from Leviticus 10:15 that the sacrificial portions, breast, and thigh of an individual's peace-offering required waving but not bringing near the Altar.[82] A Baraita explained how the priests performed the waiving. A priest placed the sacrificial portions on the palm of his hand, the breast and thigh on top of the sacrificial portions, and whenever there was a bread offering, the bread on top of the breast and thigh. Rav Papa found authority for the Baraita's teaching in Leviticus 8:26–27, which states that they placed the bread on top of the thigh. And the Gemara noted that Leviticus 10:15 implies that the breast and thigh were on top of the offerings of fat. But the Gemara noted that Leviticus 7:30 says that the priest "shall bring the fat upon the breast." Abaye reconciled the verses by explaining that Leviticus 7:30 refers to the way that the priest brought the parts from the slaughtering place. The priest then turned them over and placed them into the hands of a second priest, who waived them. Noting further that Leviticus 9:20 says that "they put the fat upon the breasts," the Gemara deduced that this second priest then handed the parts over to a third priest, who burned them. The Gemara thus concluded that these verses taught that three priests were required for this part of the service, giving effect to the teaching of Proverbs 14:28, "In the multitude of people is the king's glory."[83]

The Gemara taught that the early scholars were called soferim (related to the original sense of its root safar, "to count") because they used to count all the letters of the Torah (to ensure the correctness of the text). They used to say the vav (ו) in gachon, גָּחוֹן ("belly"), in Leviticus 11:42 marks the half-way point of the letters in the Torah. (And in a Torah Scroll, scribes write that vav (ו) larger than the surrounding letters.) They used to say the words darosh darash, דָּרֹשׁ דָּרַשׁ ("diligently inquired"), in Leviticus 10:16 mark the half-way point of the words in the Torah. And they used to say Leviticus 13:33 marks the half-way point of the verses in the Torah. Rav Joseph asked whether the vav (ו) in gachon, גָּחוֹן ("belly"), in Leviticus 11:42 belonged to the first half or the second half of the Torah. (Rav Joseph presumed that the Torah contains an even number of letters.) The scholars replied that they could bring a Torah Scroll and count, for Rabbah bar bar Hanah said on a similar occasion that they did not stir from where they were until a Torah Scroll was brought and they counted. Rav Joseph replied that they (in Rabbah bar bar Hanah's time) were thoroughly versed in the proper defective and full spellings of words (that could be spelled in variant ways), but they (in Rav Joseph's time) were not. Similarly, Rav Joseph asked whether Leviticus 13:33 belongs to the first half or the second half of verses. Abaye replied that for verses, at least, we can bring a Scroll and count them. But Rav Joseph replied that even with verses, they could no longer be certain. For when Rav Aha bar Adda came (from the Land of Israel to Babylon), he said that in the West (in the Land of Israel), they divided Exodus 19:9 into three verses. Nonetheless, the Rabbis taught in a Baraita that there are 5,888 verses in the Torah.[84] (Note that others say the middle letter in our current Torah text is the aleph (א) in hu, הוּא ("he"), in Leviticus 8:28; the middle two words are el yesod, אֶל-יְסוֹד ("at the base of"), in Leviticus 8:15; the half-way point of the verses in the Torah is Leviticus 8:7; and there are 5,846 verses in the Torah text we have today.)[85]

The Sifra taught that the goat of the sin-offering about which Moses inquired in Leviticus 10:16 was the goat brought by Nachshon ben Aminadav, as reported in Numbers 7:12, 16.[86]

The Mishnah deduced from Leviticus 10:16–20 that those in the first stage of mourning (onen), prior to the burial of their dead, are prohibited from eating the meat of sacrifices.[87] Similarly, the Mishnah derived from Leviticus 10:16–20 that a High Priest could offer sacrifices before he buried his dead, but he could not eat sacrificial meat. An ordinary priest in the early stages of mourning, however, could neither offer sacrifices nor eat sacrificial meat.[88] Rava recounted a Baraita that taught that the rule of Leviticus 13:45 regarding one with skin disease, "the hair of his head shall be loose," also applied to a High Priest. The status of a High Priest throughout the year corresponded with that of any other person on a festival (with regard to mourning). For the Mishnah said[89] the High Priest could bring sacrifices on the altar even before he had buried his dead, but he could not eat sacrificial meat. From this restriction of a High Priest, the Gemara inferred that the High Priest would deport himself as a person with skin disease during a festival. And the Gemara continued to teach that a mourner is forbidden to cut his hair, because since Leviticus 10:6 ordained for the sons of Aaron: "Let not the hair of your heads go loose" (after the death of their brothers Nadab and Abihu), we infer that cutting hair is forbidden for everybody else (during mourning), as well.[90]

A Midrash taught that when in Leviticus 10:16 "Moses diligently inquired [literally: inquiring, he inquired] for the goat of the sin-offering," the language indicates that Moses made two inquiries: (1) If the priests had slaughtered the goat of the sin-offering, why had they not eaten it? And (2) If the priests were not going to eat it, why did they slaughter it? And immediately thereafter, Leviticus 10:16 reports that Moses "was angry with Eleazar and with Ithamar," and Midrash taught that through becoming angry, he forgot the law. Rav Huna taught that this was one of three instances where Moses lost his temper and as a consequence forgot a law. (The other two instances were with regard to the Sabbath in Exodus 16:20 and with regard to the purification of unclean metal utensils Numbers 31:14.) In this case (involving Nadab and Abihu), because of his anger, Moses forgot the law[91] that those in the first stage of mourning (onen), prior to the burial of their dead, are prohibited from eating the meat of sacrifices. Aaron asked Moses whether he should eat consecrated food on the day that his sons died. Aaron argued that since the tithe (which is of lesser sanctity) is forbidden to be eaten by a bereaved person prior to the burial of his dead, how much more certainly must the meat of the sin-offering (which is more sacred) be prohibited to a bereaved person prior to the burial of his dead. Immediately after Moses heard Aaron's argument, he issued a proclamation to the Israelites, saying that he had made an error in regard to the law and Aaron his brother came and taught him. Eleazar and Ithamar had known the law, but kept their silence out of deference to Moses, and as a reward, God addressed them directly along with Moses and Aaron in Leviticus 11:1. When Leviticus 11:1 reports that "the Lord spoke to Moses and to Aaron, saying to them," Rabbi Hiyya taught that the words "to them" referred to Eleazar and Ithamar.[92]

Similarly, Rabbi Nehemiah deduced from Leviticus 10:19 that Aaron's sin-offering was burned (and not eaten by the priests) because Aaron and his remaining sons (the priests) were in the early stages of mourning, and thus disqualified from eating sacrifices.[93]

A scholar who was studying with Rabbi Samuel bar Nachmani said in Rabbi Joshua ben Levi's name that the words, "and, behold, it was burnt," in Leviticus 10:16 taught that where a priest mistakenly brought the blood of an outer sin-offering into the Sanctuary within, the priests had to burn the remainder of the offering.[94] Similarly, Rabbi Jose the Galilean deduced from the words, "Behold, the blood of it was not brought into the Sanctuary within," in Leviticus 10:18 that if a priest took the sacrifice outside prescribed bounds or took its blood within the Sanctuary, the priests were required to burn the rest of the sacrifice.[95]

The Rabbis in a Baraita noted the three uses of the word "commanded" in Leviticus 10:12–13, 10:14–15, and Leviticus-nb 10:16–18, in connection with the sacrifices on the eighth day of the inauguration of the Tabernacle, the day on which Nadab and Abihu died. The Rabbis taught that Moses said "as the Lord commanded" in Leviticus 10:13 to instruct that the priest were to eat the grain (minchah) offering, even though they were in the earliest stage of mourning. The Rabbis taught that Moses said "as I commanded" in Leviticus 10:18 in connection with the sin-offering (chatat) at the time that Nadab and Abihu died. And the Rabbis taught that Moses said "as the Lord commanded" in Leviticus 10:15 to enjoin Aaron and the priests to eat the peace-offering (shelamim) notwithstanding their mourning (and Aaron's correction of Moses in Leviticus 10:19), not just because Moses said so on his own authority, but because God had directed it.[96]

Samuel taught that the interpretation that Aaron should not have eaten the offering agreed with Rabbi Nehemiah while the other interpretation that Aaron should have eaten the offering agreed with Rabbi Judah and Rabbi Simeon. Rabbi Nehemiah argued that they burned the offering because the priests were in the first stages of mourning. Rabbi Judah and Rabbi Simeon maintained that they burned it because the offering had become defiled during the day, not because of bereavement. Rabbi Judah and Rabbi Simeon argued that if it was because of bereavement, they should have burned all three sin offerings brought that day. Alternatively, Rabbi Judah and Rabbi Simeon argued that the priest would have been fit to eat the sacrifices after sunset. Alternatively, Rabbi Judah and Rabbi Simeon argued that Phinehas was then alive and not restricted by the law of mourning.[97]

According to Rabbi Nehemiah, this is how the exchange went: Moses asked Aaron why he had not eaten the sacrifice. Moses asked Aaron whether perhaps the blood of the sacrifice had entered the innermost sanctuary, but Aaron answered that its blood had not entered into the inner sanctuary. Moses asked Aaron whether perhaps the blood had passed outside the sanctuary courtyard, but Aaron replied that it had not. Moses asked Aaron whether perhaps the priests had offered it in bereavement, and thus disqualified the offering, but Aaron replied that his sons had not offered it, Aaron had. Thereupon Moses exclaimed that Aaron should certainly have eaten it, as Moses had commanded in Leviticus 10:18 that they should eat it in their bereavement. Aaron replied with Leviticus 10:19 and argued that perhaps what Moses had heard was that it was allowable for those in mourning to eat the special sacrifices for the inauguration of the Tabernacle, but not the regular ongoing sacrifices. For if Deuteronomy 26:14 instructs that the tithe, which is of lesser holiness, cannot be eaten in mourning, how much more should that prohibition apply to sacrifices like the sin-offering that are more holy. When Moses heard that argument, he replied with Leviticus 10:20 that it was pleasing to him, and he admitted his error. Moses did not seek to excuse himself by saying that he had not heard the law from God, but admitted that he had heard it and forgot it.[97]

According to Rabbi Judah and Rabbi Simeon, this is how the exchange went: Moses asked Aaron why he had not eaten, suggesting the possibilities that the blood had entered the innermost sanctuary or passed outside the courtyard or been defiled by being offered by his sons, and Aaron said that it had not. Moses then asked whether perhaps Aaron had been negligent through his grief and allowed the sacrifice to become defiled, but Aaron exclaimed with Leviticus 10:19 that these events and even more could have befallen him, but Aaron would not show such disrespect to sacrifices. Thereupon Moses exclaimed that Aaron should certainly have eaten it, as Moses had commanded in Leviticus 10:18. Aaron argued from analogy to the tithe (as in Rabbi Nehemiah's version), and Moses accepted Aaron's argument. But Moses argued that the priests should have kept the sacrificial meat and eaten it in the evening. And to that Aaron replied that the meat had accidentally become defiled after the sacrifice.[98]

Leviticus chapter 11

Tractate Chullin in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of kashrut (כַּשְׁרוּת) in Leviticus 11 and Deuteronomy 14:3–21.[99]

Reading Leviticus 11:1, a Midrash taught that in 18 verses, Scripture places Moses and Aaron (the instruments of Israel's deliverance) on an equal footing (reporting that God spoke to both of them alike),[100] and thus there are 18 benedictions in the Amidah.[101]

A Midrash taught that Adam offered an ox as a sacrifice, anticipating the laws of clean animals in Leviticus 11:1–8 and Deuteronomy 14:4–6.[102]

Rav Hisda asked how Noah knew (before the giving of Leviticus 11 or Deuteronomy 14:3–21) which animals were clean and which were unclean. Rav Hisda explained that Noah led them past the Ark, and those that the Ark accepted (in multiples of seven) were certainly clean, and those that the Ark rejected were certainly unclean. Rabbi Abbahu cited Genesis 7:16, "And they that went in, went in male and female," to show that they went in of their own accord (in their respective pairs, seven of the clean and two of the unclean).[103]

Rabbi Tanhum ben Hanilai compared the laws of kashrut to the case of a physician who went to visit two patients, one whom the physician judged would live, and the other whom the physician judged would die. To the one who would live, the physician gave orders about what to eat and what not to eat. On the other hand, the physician told the one who would die to eat whatever the patient wanted. Thus to the nations who were not destined for life in the World to Come, God said in Genesis 9:3, "Every moving thing that lives shall be food for you." But to Israel, whom God intended for life in the World to Come, God said in Leviticus 11:2, "These are the living things which you may eat."[104]

Rav reasoned that since Proverbs 30:5 teaches that "Every word of God is pure," then the precepts of kashrut were given for the express purpose of purifying humanity.[105]

Reading Leviticus 18:4, "My ordinances (מִשְׁפָּטַי, mishpatai) shall you do, and My statutes (חֻקֹּתַי, chukotai) shall you keep," the Sifra distinguished "ordinances" (מִשְׁפָּטִים, mishpatim) from "statutes" (חֻקִּים, chukim). The term "ordinances" (מִשְׁפָּטִים, mishpatim), taught the Sifra, refers to rules that even had they not been written in the Torah, it would have been entirely logical to write them, like laws pertaining to theft, sexual immorality, idolatry, blasphemy and murder. The term "statutes" (חֻקִּים, chukim), taught the Sifra, refers to those rules that the impulse to do evil (יצר הרע, yetzer hara) and the nations of the world try to undermine, like eating pork (prohibited by Leviticus 11:7 and Deuteronomy 14:7–8), wearing wool-linen mixtures (שַׁעַטְנֵז, shatnez, prohibited by Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), release from levirate marriage (חליצה, chalitzah, mandated by Deuteronomy 25:5–10), purification of a person affected by skin disease (מְּצֹרָע, metzora, regulated in Leviticus 13–14), and the goat sent off into the wilderness (the "scapegoat," regulated in Leviticus 16). In regard to these, taught the Sifra, the Torah says simply that God legislated them and we have no right to raise doubts about them.[106]

Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah taught that people should not say that they do not want to wear a wool-linen mixture (שַׁעַטְנֵז, shatnez, prohibited by Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), eat pork (prohibited by Leviticus 11:7 and Deuteronomy 14:7–8), or be intimate with forbidden partners (prohibited by Leviticus 18 and 20), but rather should say that they would love to, but God has decreed that they not do so. For in Leviticus 20:26, God says, "I have separated you from the nations to be mine." So one should separate from transgression and accept the rule of Heaven.[107]

Rabbi Berekiah said in the name of Rabbi Isaac that in the Time to Come, God will make a banquet for God's righteous servants, and whoever had not eaten meat from an animal that died other than through ritual slaughtering (נְבֵלָה, neveilah, prohibited by Leviticus 17:1–4) in this world will have the privilege of enjoying it in the World to Come. This is indicated by Leviticus 7:24, which says, "And the fat of that which dies of itself (נְבֵלָה, neveilah) and the fat of that which is torn by beasts (טְרֵפָה, tereifah), may be used for any other service, but you shall not eat it," so that one might eat it in the Time to Come. (By one's present self-restraint one might merit to partake of the banquet in the Hereafter.) For this reason Moses admonished the Israelites in Leviticus 11:2, "This is the animal that you shall eat."[108]

Providing an exception to the laws of kashrut in Leviticus 11 and Deuteronomy 14:3–21, Rabin said in Rabbi Johanan's name that one may cure oneself with all forbidden things, except idolatry, incest, and murder.[109]

A Midrash interpreted Psalm 146:7, "The Lord lets loose the prisoners," to read, "The Lord permits the forbidden," and thus to teach that what God forbade in one case, God permitted in another. God forbade the abdominal fat of cattle (in Leviticus 3:3), but permitted it in the case of beasts. God forbade consuming the sciatic nerve in animals (in Genesis 32:33) but permitted it in fowl. God forbade eating meat without ritual slaughter (in Leviticus 17:1–4) but permitted it for fish. Similarly, Rabbi Abba and Rabbi Jonathan in the name of Rabbi Levi taught that God permitted more things than God forbade. For example, God counterbalanced the prohibition of pork (in Leviticus 11:7 and Deuteronomy 14:7–8) by permitting mullet (which some say tastes like pork).[110]

Reading Leviticus 11:2, "These are the living things that you may eat," the Sifra taught that the use of the word "these" indicates that Moses would hold up an animal and show the Israelites, and say to them, "This you may eat," and "This you may not eat."[111]

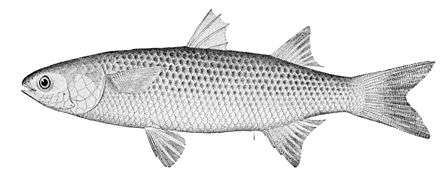

The Mishnah noted that the Torah states (in Leviticus 11:3 and Deuteronomy 14:6) the characteristics of domestic and wild animals (by which one can tell whether they are clean). The Mishnah noted that the Torah does not similarly state the characteristics of birds, but the sages taught that every bird that seizes its prey is unclean. Every bird that has an extra toe (a hallux), a crop, and a gizzard that can be peeled off is clean. Rabbi Eliezer the son of Rabbi Zadok taught that every bird that parts its toes (evenly) is unclean.[112] The Mishnah taught that among locusts, all that have four legs, four wings, jointed legs (as in Leviticus 11:21), and wings covering the greater part of the body are clean. Rabbi Jose taught that it must also bear the name "locust." The Mishnah taught that among fish, all that have fins and scales are clean. Rabbi Judah said that it must have (at least) two scales and one fin (to be clean). The scales are those (thin discs) that are attached to the fish, and the fins are those (wings) by which it swims.[113]

The Mishnah taught that hunters of wild animals, birds, and fish, who chanced upon animals that Leviticus 11 defined as unclean were allowed to sell them. Rabbi Judah taught that a person who chanced upon such animals by accident was allowed to buy or sell them, provided that the person did not make a regular trade of it. But the sages did not allow it.[114]

Rav Shaman bar Abba said in the name of Rav Idi bar Idi bar Gershom who said it in the name of Levi bar Perata who said it in the name of Rabbi Nahum who said it in the name of Rabbi Biraim who said it in the name of a certain old man named Rabbi Jacob that those of the Nasi's house taught that (cooking) a forbidden egg among 60 (permitted) eggs renders them all forbidden, (but cooking) a forbidden egg among 61 (permitted) eggs renders them all permitted. Rabbi Zera questioned the ruling, but the Gemara cited the definitive ruling: It was stated that Rabbi Helbo said in the name of Rav Huna that with regard to a (forbidden) egg (cooked with permitted ones), if there are 60 besides the (forbidden) one, they are (all) forbidden, but if there are 61 besides the (forbidden) one, they are permitted.[115]

The Mishnah taught the general rule that wherever the flavor from a prohibited food yields benefit, it is prohibited, but wherever the flavor from a prohibited food does not yield benefit, it is permitted. For example, if (prohibited) vinegar fell into split beans (it is permitted).[116]

Reading Leviticus 11:7, "the swine, because it parts the hoof, and is cloven-footed, but does not chew the cud, is unclean to you," a Midrash compared the pig to the Roman Empire. Just as the swine when reclining puts out its hooves as if to say, "See that I am clean," so too the Roman Empire boasted (of its virtues) as it committed violence and robbery under the guise of establishing justice. The Midrash compared the Roman Empire to a governor who put to death the thieves, adulterers, and sorcerers, and then leaned over to a counselor and said: "I myself did these three things in one night."[117]

Reading Leviticus 11:29–38, the Mishnah compared human blood to the blood of domestic animals in one respect, and to the blood of reptiles in another respect. The Mishnah noted that human blood is like the blood of animals in that it renders seeds susceptible to impurity (by virtue of Leviticus 11:34–38) and like the blood of reptiles in that one would not be liable to extirpation (כרת, karet) on account of consuming it. (Leviticus 7:26 forbids consuming the blood of animals, but not the blood of reptiles.)[118]

On the day when Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah displaced Rabban Gamaliel II as Principal of the School, Rabbi Akiva expounded on the words of Leviticus 11:33, "and every earthen vessel, into which any of them falls, whatsoever is in it shall be unclean." Rabbi Akiva noted that Leviticus 11:33 does not state "is unclean" but "will make others unclean." Rabbi Akiva deduced from this that a loaf that is unclean in the second degree (when, for example, the vessel becomes unclean first and then defiles the loaf in it), can make whatever it comes in contact with unclean in the third degree. Rabbi Joshua asked who would remove the dust from the eyes of Rabban Johanan ben Zakai (so that he might hear this wonderful proof), as Rabban Johanan ben Zakai said that another generation would pronounce clean a loaf that was unclean in the third degree on the ground that there is no text in the Torah according to which it would be unclean. Rabbi Joshua noted that Rabbi Akiva, the intellectual descendant of Rabban Johanan ben Zakai (as Rabbi Akiva was the pupil of Rabbi Eliezer ben Hurcanus, a disciple of Rabban Johanan ben Zakai), adduced a text in the Torah — Leviticus 11:33 — according to which such a loaf was unclean.[119]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[120]

Leviticus chapter 9

Reading the words of Moses in Leviticus 9:4, "today the Lord will appear to you," Ibn Ezra taught that Moses referred to the fire that came forth from God.[121]

Leviticus chapter 11

Judah Halevi expressed admiration for those who first divided the Torah's text into verses, equipped it with vowel signs, accents, and masoretic signs, and counted the letters so carefully that they found that the gimel (ג) in gachon, גָּחוֹן ("belly"), in Leviticus 11:42 stands at the exact middle of the Torah.[122] (Note, however, the Gemara's report, discussed in "classical rabbinic interpretation" above, that some said that the vav (ו) in gachon, גָּחוֹן, marks the half-way point of the Torah.[84])

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Leviticus chapter 10

Professor James Kugel of Bar Ilan University reported that according to one theory, the Priestly source (often abbreviated P) invented Nadab and Abihu, giving them the names of the discredited King Jeroboam’s sons, so that they could die in the newly inaugurated sanctuary (as noted in Leviticus 16:1) and thereby defile it through corpse contamination, so that God could then instruct Aaron in Leviticus 16:3 about how to purify the sanctuary through Yom Kippur. This theory posited that the Israelites had originally used Yom Kippur’s purification procedure any time it was needed during the year, and thus it made sense to the narrative to have the sanctuary contaminated (in Leviticus 10) and then immediately purged (in Leviticus 16), but eventually, when the Israelites made sanctuary purgation an annual rite, the Priestly source inserted Leviticus 11–15 to list other potential sources of impurity that might require the sanctuary to be purged.[123]

Professor Jacob Milgrom, formerly of the University of California, Berkeley, noted that Leviticus 10:8–15 sets forth some of the few laws (along with Leviticus 6:1–7:21 and 16:2–28) reserved for the Priests alone, while most of Leviticus is addressed to all the Israelite people.[124]

Leviticus chapter 11

Professor Robert A. Oden, formerly of Dartmouth College, argued that the reason for the Priestly laws of kashrut in Leviticus 11 was the integrity of Creation and what the world's created order looked like. Those things that cohere with the comprehensiveness of the created cosmology are deemed good.[125]

Kugel reported that the Israeli archaeologist Israel Finkelstein found no pig bones in hilltop sites starting in the Iron I period (roughly 1200–1000 BCE) and continuing through Iron II, while before that, in Bronze Age sites, pig bones abounded. Kugel deduced from Finkelstein’s data that the new hilltop residents were fundamentally different from both their predecessors in the highlands and the city Canaanites — either because they were a different ethnic group, or because they had adopted a different way of life, for ideological or other reasons. Kugel inferred from Finkelstein’s findings that these highlanders shared some ideology (if only a food taboo), like modern-day Jews and Muslims. And Kugel concluded that the discontinuities between their way of life and that of the Canaanite city dwellers and earlier highland settlers supported the idea that the settlers were not exurbanites.[126]

Interpreting the laws of kashrut in Leviticus 11 and Deuteronomy 14:3–21, in 1997, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of Conservative Judaism held that it is possible for a genetic sequence to be adapted from a non-kosher species and implanted in a new strain of a kosher foodstuff — for example, for a gene for swine growth hormone to be introduced into a potato to induce larger growth, or for a gene from an insect to be introduced into a tomato plant to give it unusual qualities of pest resistance — and that new strain to be kosher.[127] Similarly, in the late 1990s, the Central Conference of American Rabbis of Reform Judaism ruled that it is a good thing for a Jew who observes kashrut to participate in a medical experiment involving a pork byproduct.[128]

Commandments

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 6 positive and 11 negative commandments in the parashah:[129]

- A Kohen must not enter the Temple with long hair.[130]

- A Kohen must not enter the Temple with torn clothes.[130]

- A Kohen must not leave the Temple during service.[131]

- A Kohen must not enter the Temple intoxicated.[132]

- To examine the signs of animals to distinguish between kosher and non-kosher.[133]

- Not to eat non-kosher animals[134]

- To examine the signs of fish to distinguish between kosher and non-kosher[135]

- Not to eat non-kosher fish[136]

- Not to eat non-kosher fowl[137]

- To examine the signs of locusts to distinguish between kosher and non-kosher[138]

- To observe the laws of impurity caused by the eight insects[139]

- To observe the laws of impurity concerning liquid and solid foods[140]

- To observe the laws of impurity caused by a dead beast[141]

- Not to eat non-kosher creatures that crawl on land[142]

- Not to eat worms found in fruit on the ground[143]

- Not to eat creatures that live in water other than fish[144]

- Not to eat non-kosher maggots[145]

Haftarah

In general

The haftarah for the parashah is:

Summary

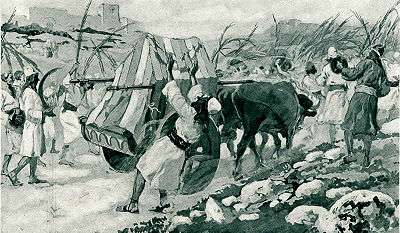

David gathered together all the chosen men of Israel — 30,000 in all — and went to retrieve the Ark of the Covenant from Baale-judah.[146] They brought the Ark out of the house of Abinadab and set it on a new cart, and Abinadab's sons Uzzah and Ahio drove the cart, with Ahio going before the Ark.[147] David and the Israelites played with all manner of instruments — harps, psalteries, timbrels, sistra, and cymbals.[148] When they came to the threshing-floor of Nacon, the oxen stumbled, and Uzzah put out his hand to the Ark.[149] In anger, God smote Uzzah for his error, and Uzzah died by the Ark.[150]

Displeased and afraid, David questioned how the Ark could come to him.[151] So David took the Ark to the house of Obed-Edom the Gittite and left it there for three months, during which time God blessed Obed-Edom and his house.[152]

When David heard that God had blessed Obed-Edom because of the Ark, David brought the Ark to Jerusalem with joy.[153] When those who bore the Ark had gone six paces, they sacrificed an ox and a fatling.[154] The Israelites brought up the Ark with shouting and the sound of the horn, and David danced with all his might girded with a linen ephod.[155] As the Ark came into the city, Michal the daughter of Saul looked out the window and saw David leaping and dancing, and she despised him in her heart.[156]

They set the Ark in a tent that David pitched for it, David offered burnt-offerings and peace-offerings, and David blessed the people in the name of the Lord.[157] David distributed a sweet cake of bread to all the people of Israel, and the people departed to their houses.[158] (The Haftarah ends at this point for Sephardi Jews, but continues for Ashkenazi Jews.)

When David returned to bless his household, Michal came out to meet him with scorn, taunting him for uncovering himself before his servants' handmaids.[159] David retorted to Michal that he danced before the God who had chosen him over her father, and that he would be viler than that.[160] Michal never had children thereafter.[161]

God gave David rest from his enemies, and David asked Nathan the prophet why David should dwell in a house of cedar, while the Ark dwelt within curtains.[162] At first Nathan told David to do what was in his heart, but that same night God directed Nathan to tell David not to build God a house, for God had not dwelt in a house since the day that God had brought the children of Israel out of Egypt, but had abided in a tent and in a tabernacle.[163] God directed Nathan to tell David that God took David from following sheep to be a prince over Israel, God had been with David wherever he went, and God would make David a great name.[164] God would provide a place for the Israelites at rest from their enemies, God would make David into a dynasty, and when David died, God would see that David's son would build a house for God's name.[165] God would be to David's son a father, and he would be to God a son; if he strayed, God would chasten him, but God's mercy would not depart from him.[166] David's kingdom would be established forever.[167] And Nathan told David everything in his vision.[168]

Connection to the parashah

Both the parashah and the haftarah report efforts to consecrate the holy space followed by tragic incidents connected with inappropriate proximity to the holy space. In the parashah, Moses consecrated the Tabernacle, the home of the Ark of the Covenant,[169] while in the haftarah, David set out to bring the Ark to Jerusalem.[170] Then in the parashah, God killed Nadab and Abihu "when they drew near" to the Ark,[171] while in the haftarah, God killed Uzzah when he "put forth his hand to the Ark."[172]

On Shabbat Parah

When the parashah coincides with Shabbat Parah (the special Sabbath prior to Passover — as it does in 2014), the haftarah is:

- for Ashkenazi Jews: Ezekiel 36:16–38

- for Sephardi Jews: Ezekiel 36:16–36

On Shabbat Parah, the Sabbath of the red heifer, Jews read Numbers 19:1–22, which describes the rites of purification using the red heifer (parah adumah). Similarly, the haftarah in Ezekiel 36 also describes purification. In both the special reading and the haftarah in Ezekiel 36, sprinkled water cleansed the Israelites.[173]

On Shabbat Machar Chodesh

When the parashah coincides with Shabbat Machar Chodesh (as it does in 2015), the haftarah is 1 Samuel 20:18–42.

Notes

- ↑ "Torah Stats — VaYikra". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- ↑ "Parashat Shmini". Hebcal. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ↑ See Hebcal Jewish Calendar and compare results for Israel and the Diaspora.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Vayikra/Leviticus. Edited by Menachem Davis, pages 52–73. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2008. ISBN 1-4226-0206-0.

- ↑ Leviticus 9:1–4.

- ↑ Leviticus 9:5.

- ↑ Leviticus 9:8–16.

- ↑ Leviticus 9:17–21.

- ↑ Leviticus 9:22.

- 1 2 Leviticus 9:23.

- ↑ Leviticus 9:24.

- ↑ Leviticus 10:1.

- ↑ Leviticus 10:2.

- ↑ Leviticus 10:3.

- ↑ Leviticus 10:4.

- ↑ Leviticus 10:6–7.

- ↑ Leviticus 10:8–11.

- ↑ Leviticus 10:12–13.

- ↑ Leviticus 10:14.

- ↑ Leviticus 10:16–18.

- ↑ Leviticus 10:19.

- ↑ Leviticus 10:20.

- ↑ Leviticus 11.

- ↑ Leviticus 11:45

- ↑ See, e.g., "A Complete Triennial Cycle for Reading the Torah" (PDF). The Jewish Theological Seminary. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ↑ For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer. “Inner-biblical Interpretation.” In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1835–41. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-19-997846-5.

- ↑ See generally Walter C. Kaiser Jr., "The Book of Leviticus," in The New Interpreter's Bible, volume 1, page 1067. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994. ISBN 0-687-27814-7.

- ↑ James L. Kugel. How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, page 327. New York: Free Press, 2007. ISBN 0-7432-3586-X.

- ↑ For more on early nonrabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Esther Eshel. “Early Nonrabbinic Interpretation.” In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1841–59.

- ↑ On Dreams 2:9:67. Alexandria, Egypt, early 1st century CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge, page 392. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1993. ISBN 0-943575-93-1.

- ↑ On Flight and Finding 11:59. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge, page 326.

- ↑ Antiquities 3:8:7. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, page 92. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

- ↑ Letter of Aristeas 151–52. Alexandria, 3rd–1st Centruty BCE. Translated by R.J.H. Shutt. In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Volume 2: Expansions of the "Old Testament" and Legends, Wisdom and Philosophical Literature, Prayers, Psalms, and Odes, Fragments of Lost Judeo-Hellenistic works. Edited by James H. Charlesworth, pages 22–23. New York: Anchor Bible, 1985. ISBN 0-385-18813-7.

- ↑ For more on classical rabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Yaakov Elman. “Classical Rabbinic Interpretation.” In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1859–78.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Gittin 60a. Babylonia, 6th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Yitzchok Isbee and Mordechai Kuber; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, volume 35, page 60a3 and note 31. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1993. ISBN 1-57819-641-8.

- 1 2 Babylonian Talmud Megillah 10b. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Gedaliah Zlotowitz and Hersh Goldwurm; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, volume 20, page 10b2. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1991. ISBN 1-57819-620-5.

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah 14:21. 12th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 6, pages 635–36. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- ↑ Leviticus Rabbah 11:6. Land of Israel, 5th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 141–43. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 4a. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Yoma. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 9, page 15. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2013. ISBN 978-965-301-570-8.

- ↑ Jerusalem Talmud Moed Katan 17a. Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Elucidated by Chaim Ochs, Avrohom Neuberger, Mordechai Smilowitz, and Mendy Wachsman; edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volume 28, page 17a3–4. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2012. ISBN 1-4226-0255-9

- ↑ Midrash Tanhuma Shemini 1. 6th–7th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Metsudah Midrash Tanchuma. Translated and annotated by Avraham Davis; edited by Yaakov Y.H. Pupko, volume 5, pages 135–37. Monsey, New York: Eastern Book Press, 2006.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 87b. See also Sifra Shemini Mekhilta deMiluim 99:1:3. Land of Israel, 4th century CE. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifra: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, pages 124–25. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988. ISBN 1-55540-206-2.

- ↑ See Genesis 1:1–5.

- ↑ See Numbers 7:10–17.

- ↑ See Leviticus 9:1–21.

- ↑ See Leviticus 9:24.

- ↑ See Exodus 25:8.

- ↑ See Leviticus 9:22, employing the blessing prescribed by Numbers 6:22–27.

- ↑ See Leviticus 17:3–4.

- ↑ See Exodus 12:2.

- ↑ Leviticus Rabbah 11:6. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 141–42.

- ↑ Genesis Rabbah 48:5. Land of Israel, 5th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 1, page 407. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- ↑ Sifra Shemini Mekhilta deMiluim 99:5:1. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifra: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, page 133.

- ↑ Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 53. Early 9th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer. Translated and annotated by Gerald Friedlander, pages 429–30. London, 1916. Reprinted New York: Hermon Press, 1970. ISBN 0-87203-183-7.

- ↑ Sifra Shemini Mekhilta deMiluim 99:5:4. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifra: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2.

- ↑ Leviticus 10:2 and 16:1; Numbers 3:4 and 26:61; and 1 Chronicles 24:2.

- 1 2 3 Numbers Rabbah 2:23.

- ↑ Sifra Shemini Mekhilta deMiluim 99:5:6.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 52a.

- ↑ Sifra Shemini Mekhilta deMiluim 99:5:7. Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 52a.

- ↑ Leviticus Rabbah 20:8. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, page 259. See also Numbers Rabbah 2:23.

- ↑ Leviticus Rabbah 20:9. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 259–60.

- ↑ Leviticus Rabbah 20:10. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, page 260.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Eruvin 63a. See also Sifra Shemini Mekhilta deMiluim 99:5:6.

- ↑ Sifra Shemini Mekhilta deMiluim 99:3:4. See also Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 52a. Leviticus Rabbah 20:10. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 260–61.

- ↑ Midrash Tanhuma Beha'aloscha 16. See also Leviticus Rabbah 20:10. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 260–62.

- ↑ Leviticus Rabbah 10:5. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 126–29.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 115b. See also Leviticus Rabbah 12:2. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 155–56.

- ↑ Midrash Tanhuma Shemini 1.

- ↑ Sifra Shemini Mekhilta deMiluim 99:3:6. See also 99:5:9.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Sukkah 25a–b.

- ↑ Tosefta Berakhot 4:17. Land of Israel, circa 300 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, page 26. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Moed Katan 28b.

- ↑ Leviticus Rabbah 12:1. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 152, 155.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Gittin 60a–b. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Yitzchok Isbee and Mordechai Kuber; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, volume 35, pages 60a3–b1.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 76b–77a.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Taanit 26b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Taanit 17b; Sanhedrin 22b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 22b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 87a. See also Sifra Parashat Shemini Pereq 1, 101:1:2.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 61a; Taanit 15b.

- ↑ Mishnah Menachot 5:6. Land of Israel, circa 200 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 743. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4. Babylonian Talmud Menachot 61a.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Menachot 62a.

- 1 2 Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 30a.

- ↑ E.g., Michael Pitkowsky, "The Middle Verse of the Torah" and the response of Reuven Wolfeld there.

- ↑ Sifra Shemini Prereq 102:1.

- ↑ Mishnah Pesachim 8:8. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 246. Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 91b.

- ↑ Mishnah Horayot 3:5. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 695. Babylonian Talmud Horayot 12b.

- ↑ Mishnah Horayot 3:5. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 695. Babylonian Talmud Horayot 12b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Moed Katan 14b.

- ↑ See Mishnah Pesachim 8:8. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 246. Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 91b.

- ↑ Leviticus Rabbah 13:1. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 162–64.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 82b. See also Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 101a.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 23b.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 83a.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 5b; Zevachim 101a.

- 1 2 Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 101a.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 101a–b.