Saintonge War

| Saintonge War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Capetian-Plantagenet rivalry | |||||||

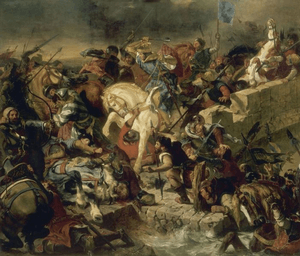

St. Louis IX at the Battle of Taillebourg, by Eugène Delacroix | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The Saintonge War was a feudal dynastic encounter that occurred in 1242 and 1243 between forces of Louis IX of France and those of Henry III of England. Saintonge is the region around Saintes in the centre-west of France. The conflict arose because some vassals of Louis were displeased with the accession of his brother, Alphonse, as Count of Poitou. The French decisively defeated the English at the Battle of Taillebourg and concluded the struggle at the Siege of Saintes. Because of dynastic sensibilities and the desire to go on a crusade, Louis did not annex Guyenne.

Prelude

By the terms of his will Louis VIII had left Poitou as an appanage to his younger son Alphonse. In June 1241, Louis IX held a plenary court at Saumur in Anjou and announced that Alphonse, having come of age, was ready to come into possession. Many nobles from Aquitaine attended the court, among them Isabella of Angoulême and her husband, the Count of La Marche, Hugh de Lusignan. After the meeting at Saumur, Louis went to Poitiers and installed his brother as the Count of Poitiers. The Lusignans were not receptive to Capetian authority in the region. Isabella was particularly frustrated that her son, the Earl of Cornwall and brother to King Henry III, had not got the title. Shortly after his arrival at Poitiers, Louis learned that Hugh had assembled an army of men-at-arms at the nearby town of Lusignan. Talks between Louis and Alphonse and Hugh and Isabella did not resolve the dispute.

In April 1242, Louis assembled a force at Chinon that some contemporaries estimated at around 50,000. On May 20, 1242, Henry arrived at Royan and joined the rebelling French nobles, forming an army that may have numbered about 30,000.[1] The two kings exchanged letters, but these resolved nothing.

Battle of Taillebourg

Henry advanced to Tonnay-Charente by mid-July and Louis moved to Saint-Jean-d'Angély, just north of Taillebourg, the armies intending to reach the bridge across the Charente River, located in the commune of Taillebourg. Henry and Hugh positioned their army near the village of Saint-James on the west bank of the river and camped in the neighbouring field, while Louis was welcomed to the fortified chateau of Geoffroy de Rancon, the Count of Taillebourg. Henry decided to send an advance guard to protect the left bank of the Taillebourg bridge, a move that led to a sharp encounter with some French troops on either July 21 or 22. Louis decided to follow up this engagement and launched a full offensive with the entire French army. The aggressive French assaults carried the day and the English king fled south to the town of Saintes, along with the revolting barons.

Siege of Saintes

On July 22 or 23, the French army laid siege to the city of Saintes. Henry realised that Hugh did not have as much support as he may have earlier claimed and withdrew to Bordeaux. It is uncertain if there were was any armed conflict associated with the siege. Recognising that he was in a hopeless position, Hugh surrendered to Louis on July 24, ending the Saintonge War.

Aftermath

Casualties are unknown, but were probably not heavy. Hugh's revolt and Henry's assistance were primarily aimed at exploiting the diversion provided by French involvement in the Albigensian Crusades. Raymond VII of Toulouse led a revolt in May 1242, but his allies revoked their support after the English were defeated; Raymond submitted to the king's authority at Montargis in January 1243. Louis did not take advantage of his victory by annexing the Plantagenet fief of Guyenne, probably because he was mostly concerned with going on the Seventh Crusade in 1248. He allowed Henry to do homage without inflicting further punishment.

Notes

- ↑ These figures may have been exaggerated.

- Kohn, George Childs (31 October 2013). Dictionary of Wars. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-95494-9.