Robert Laws

| Robert Laws | |

|---|---|

Missionaries at Bandawe, c. 17 May 1914, after ordination of the first three African clergy. Seated (L-R) Yesaya Zerenji Mwasi, Hezekiah Mavuvu Tweya, Jonathan P. Chirwa; Standing (L-R) A.G. MacAlpine, W.A. Elmslie, Robert Laws. | |

| Religion | Christian |

| Church | United Presbyterian Church of Scotland |

| Alma mater | University of Aberdeen |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1851 |

| Died | 1934 |

Dr Robert Laws (1851–1934) was a Scottish missionary who headed the Livingstonia mission in the Nyasaland Protectorate (now Malawi) for more than 50 years. The mission played a crucial role in educating Africans during the colonial era. It emphasized skills with which the pupils could become self-sufficient in trade, agriculture or industry as opposed to working as subordinates to European settlers.[1] Dr Laws supported the aspirations of political leaders such as Simon Muhango and Levi Zililo Mumba, both educated at Livingstonia schools.[2]

Early years

Robert Laws was born in 1851 in the Mannofield district of Aberdeen, Scotland, to a poor but religious family. His father, Robert Laws snr of Old Aberdeen, and his mother, Christian née Cruikshank of Kidshill in Buchan, Aberdeenshire, both attended St Nicholas Lane United Presbyterian Church, Aberdeen. His mother, Christian, has been described as having "a calm and sunny temperament, sound judgement, and gentle ways."[3] She died in 1853 in her son's infancy. Robert's stepmother was to be Isabella Cormack (d. 1893), also of Aberdeen. Robert's daughter Dr Amelia Nyasa Laws (1886 - 1978) has written that, "The child's stepmother was upright in character, kind at heart, but stern in manner, ordering him to sit still until she gave him permission to do otherwise. To this discipline he ascribed his capacity to listen, to refrain from comment, and in later years to assess the value of statements made in ignorance before discussing or correcting them."[4]

Laws was apprenticed to a cabinet maker as a youth. After reading David Livingstone's Travels he resolved to become a missionary. While working in the day he attended evening classes and managed to gain admission to the University of Aberdeen. He spent seven years there, earning degrees in Arts, Medicine and Theology.[5]

Early missionary activity 1875–1894

Laws was a member of the original Livingstonia mission party, organized by a Scottish committee dedicated to establishing a mission in memory of David Livingstone.[6] The expeditionary party was led by Captain E.D. Young, a naval officer who had been attached to Livingstone's first Zambezi expedition in 1852, and in 1867 had led the expedition to search for Livingstone around Lake Malawi. Robert Laws, of the United Presbyterian Church, was the only ordained missionary. Five artisans were included in the first expedition: a sailor, an engineer, a gardener, a blacksmith and a carpenter.[7]

The mission arrived at the south end of Lake Malawi on 12 October 1875 and established a base at Cape Maclear.[6] Laws wrote to Dr. James Stewart, the principal of the Lovedale Institution for Xhosa in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, describing the mission and calling for African catechists. Stewart, who had been a prime mover in getting the Livingstonia Mission launched, asked for volunteers. Four were selected and traveled with Stewart to Cape Maclear, leaving in July 1876.[8] Stewart took over the leadership from E.D. Young, but found conditions too arduous and left in December 1877, handing the leadership to Laws as a temporary measure. Laws remained leader for the next fifty years.[9]

Laws was a fully qualified doctor. He used chloroform for the first time at Cape Maclear on 2 March 1876 in a successful operation to remove a cystic tumour above the right eye of a young man, to the astonishment of the local people.[10] In the late 1870s it became known that the Presbyterian mission could provide superior medical assistance, and missionaries from other stations would make difficult and sometimes dangerous journeys to obtain care from Dr. Laws.[11]

In 1878 the Free Church of Scotland transferred ownership of the Ilala steamer from the mission to the Livingstonia Central Africa Company. Founded in Glasgow in 1875, the company soon became known as the African Lakes Corporation.[12] Laws collaborated with this Corporation, which succeeded in introducing trade to the lake region and the hinterland to the north, bringing prosperity to both Africans and settlers.[13]

By 1878 the mission had established small stations at Bandawe in Tonga country and at Kaningina on the edge of Ngoni country.[6] In September that year Laws reached the Ngoni village of Chiputula Nhlane, a few miles east of today's Ekwendeni, accompanied by three other Europeans and forty-five porters. Relations between the missionaries and Ngoni were strained during the next twelve years, until the first Ngoni were converted to Christianity. When Laws took his first home leave in 1884, he told the Livingstonia Committee that the Angoni were the dominant race, and the great object of the mission should be to win them over. The Ngoni were less certain about the advantages, and were distracted by internal instability and struggles with neighboring tribes.[14]

Livingstonia 1894–1927

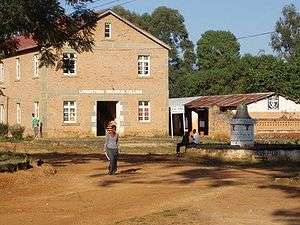

In 1881 the mission moved to Bandawe in Tonga country to escape the bad climate and unhealthy conditions of Cape Maclear, and in 1894 moved once again to Khondowe for health reasons.[6] Today a stone cairn marks the place where Dr. Laws and his companion Uriah Chirwa camped in 1894 when they prospected the new site.[15] Khondowe is 900 metres (3,000 ft) above the lake. It has a healthy climate, fertile land and plentiful water. Within ten years the site had grown into a small village of brick and stone buildings, many of which are still in use.[16]

When Laws laid out plans for the Overtoun Institution in Khondowe, now known as Livingstonia, his design was practical. Roads and avenues were carefully laid out, and zones designated for different industrial and agricultural activities. The plans included a sawmill and brickworks, a piped water supply, a church and post office with a clock tower, buildings housing the agricultural, medical and technical departments, and separate housing for Europeans and Africans. The site was connected to the lake by a telegraph line. The boys helped build the post office and plant trees.[17] Laws later introduced hydroelectric power for lighting and to run the machinery.[13]

Based on Laws' experience with Khondowe and knowledge of Lovedale, the mission society sent Robert Laws to undertake a feasibility study of a similar institution in Calabar, Nigeria, to be known as the Hope Waddell Training Institute (HWTI). As with the other two institutions, the goals were to equip graduates with the skills needed in a modern economy so that they could improve their living standards and those of the community. Laws was entirely confident that the HWTI could replicate the excellent results of the two earlier institutes.[18] The school, named after the Reverend Hope Masterton Waddell, was launched in 1895.[19]

At Livingstonia Dr Laws trained Africans in engineering, entrepreneurship, bookkeeping, teaching and the ministry. By 1897 there were 302 pupils. Many of the graduates found the skills they had acquired could be put to use in South Africa and the Rhodesias.[13] The Livingstonia mission was the main source of education for Africans in Nyasaland, and in the early years of the twentieth century had more schools than all the other missions added together. Men educated in these schools were to have growing political influence. The first Native Association, the North Nyasa Native Association, was founded by Simon Muhango and Levi Zililo Mumba in 1912, and was soon followed by others. From the outset, Dr Laws encouraged the Associations. He felt that the government had to involve the new class of educated Africans if Nyasaland was to develop into a modern country. He went as far as to say that the Associations could prepare Africans to elect Europeans, and later Africans, to the Legislature. Given the typical colonial prejudices of the time, this was an exceptional position.[2]

In October 1925, the Governor of Nyasaland, Charles Calvert Bowring, laid the foundation stone for additional buildings at Livingstonia, which Dr Robert Laws wanted to develop into a university for African students in Nyasaland and neighboring colonies. Bowring wrote "Livingstonia appeals to me enormously as a training centre because of its comparative isolation and at the same time easy accessibility. The students are away from the many temptations of town life, and within easy reach by the lake and in touch by telegraph".[20]

Dr. Laws visited Canada, the United States and Germany. He served on the legislative council of Nyasaland. When he left in 1927 there were over seven hundred primary schools, and secondary schools were teaching theology, medicine, agriculture and technical subjects. More than 60,000 people had accepted Christianity and there were thirteen ordained African pastors.[21]

Family

In 1879, Laws married Margaret Troup Gray. Margaret Gray was a childhood companion from St Nicholas Lane United Presbyterian Church Sunday School in Aberdeen. The two had also volunteered together at Aberdeen's Shiprow Mission for the city's working youth.[3] The young couple shared an unwavering commitment to the mission field and married in Blantyre, Malawi, where St Michael and All Angels Church was to be constructed a decade later. They had eight children, but only one daughter, Amelia Nyasa Laws, born in 1886, survived.[22] Amelia Nyasa Laws was to lead a distinguished life as a medical practitioner, dying in 1978.[23]

Character

Discussing the lack of penetration of Christianity into central Africa before the late nineteenth century. Laws said "that God could not trust Christendom with the knowledge of it until the Christian conscience was awake ... to the iniquity of slavery".[24]

Laws was austere and uncomfortable with speaking in public, but immensely energetic. As a doctor he took responsibility for the health of the mission party and for hundreds of out-patients.[9] He recorded meteorological conditions, gathered vocabularies of the local languages, taught the first pupils at the mission and undertook a vast official correspondence. In the first ten years he led almost every diplomatic or exploratory mission, and took almost all important decisions for the mission.[9]

Laws aimed to teach Africans the skills needed to run trades and small industries so they would not be at the mercy of the "Greeks, Indians and Chinese". He was strongly opposed to the view of African education which held that "the native should be kept in his place".[25] However, although in many ways a visionary, Laws did not make much provision for women for receive comparable education to men.[26] Jane Elizabeth Waterston arrived in 1879 after training for her single ambition to work at Livingstonia. She left after a few months because of the poor respect she saw for Africans and herself.[27] Laws believed in Western technology as a catalyst in developing an environment in which conversion to Christianity would be facilitated. He saw great importance in piped water and electricity, and relied on the lake steamer to bring his religion to the people.[28]

A columnist in the Glasgow Evening Citizen wrote of Dr. Laws after his death in 1934 "Nothing impressed me more about Dr Laws than his humility. He was a great man who was unconscious of his greatness".[29]

Bibliography

- Laws, Robert (1894). An English-Nyanja Dictionary. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 1-103-14221-6.

- Laws, Robert (1934). Reminiscences of Livingstonia. Edinburgh.

References

- ↑ Fisk 1994, pp. 77ff.

- 1 2 Ross 2009, p. 23.

- 1 2 Livingstone 1921, p. 1ff.

- ↑ McIntosh 1933, p. 1ff.

- ↑ Fisk 1994, p. 79.

- 1 2 3 4 Thompson 1995, p. ix.

- ↑ McCracken 2008, p. 63.

- ↑ Thomson 2007, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 McCracken 2008, p. 69.

- ↑ Diz et al. 2002.

- ↑ Good 2004, p. 14.

- ↑ Good 2004, p. 62.

- 1 2 3 Good 2004, p. 45.

- ↑ Thompson 1995, p. 30.

- ↑ Murphy 2007, pp. 180.

- ↑ Briggs 2010, p. 290.

- ↑ Porter 2003, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Taylor 1996, pp. 138.

- ↑ Archibong 2005.

- ↑ McCracken 2008, p. 279.

- ↑ Douglas & Comfort 1992, p. 416.

- ↑ Robert Laws of Livingstonia and Amelia Laws: papers.

- ↑ Lothian Health Services Archive 2011.

- ↑ McCracken 2008, p. 44.

- ↑ Thompson 1995, p. 243.

- ↑ Lamba 2010, p. 125.

- ↑ Elizabeth van Heyningen, ‘Waterston, Jane Elizabeth (1843–1932)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, May 2006 accessed 10 Sept 2015

- ↑ Porter 2003, p. 114.

- ↑ Randall 2009, p. 5.

Sources

- Archibong, Maurice (February 17, 2005). "Hope Waddell, a Nigerian metaphor". The Sun (Nigeria). Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- Briggs, Philip (2010). Malawi. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 1-84162-313-X.

- Diz, José Carlos; Franco, Avelino; Bacon, Douglas R.; Rupreht, J.; Alvarez, Julián (2002). The history of anesthesia: proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on the History of Anesthesia, Santiago, Spain, 19-23 September 2001. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 0-444-51293-4.

- Douglas, J. D.; Comfort, Philip Wesley (1992). "Laws, Robert (1851-1934)". Who's Who in Christian History. Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-8423-1014-2.

- Lothian Health Services Archive (19 August 2011). "Charting our cataloguing progress". Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- Fisk, Samuel (1994). "Dr. Robert Laws: Missionary Extraordinary". More Fascinating Conversion Stories. Kregel Publications. ISBN 0-8254-2640-5.

- Good, Charles M. (2004). The steamer parish: the rise and fall of missionary medicine on an African frontier. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226302822.

- Lamba, Isaac Chikwekwere (2010). Contradictions in Post-War Education Policy Formation and Application in Colonial Malawi 1945-1961. African Books Collective. ISBN 99908-87-94-2.

- Livingstone, William Pringle (1921). Laws of Livingstonia: A Narrative of Missionary Adventure and Achievement. Hodder and Stoughton.

- McIntosh, Hamish (1933). Robert Laws: servant of Africa. Handsel.

- McCracken, John (2008). Politics and Christianity in Malawi, 3ed: The Impact of the Livingstonia Mission in the Northern Province. African Books Collective. ISBN 99908-87-50-0.

- Murphy, Alan (2007). "Livingstonia". Southern Africa. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74059-745-1.

- Porter, Andrew N. (2003). The imperial horizons of British Protestant missions, 1880-1914. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-6087-7.

- Randall, David J. (2009). Grace Sufficient. African Books Collective. ISBN 99908-87-59-4.

- "Robert Laws of Livingstonia and Amelia Laws: papers". University of Aberdeen Archival Database. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- Ross, Andrew C. (2009). Colonialism to cabinet crisis: a political history of Malawi. African Books Collective. ISBN 99908-87-75-6.

- Taylor, William H. (1996). Mission to educate: a history of the educational work of the Scottish Presbyterian mission in East Nigeria, 1846-1960. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10713-4.

- Thompson, T. Jack (1995). Christianity in northern Malaŵi: Donald Fraser's missionary methods and Ngoni culture. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10208-6.

- Thomson, Jack (2007). Ngoni, Xhosa and Scot: religious and cultural interaction in Malawi. African Books Collective. ISBN 99908-87-15-2.

Further reading

- McIntosh, Hamish (1993). Robert Laws: servant of Africa. Handsel. ISBN 1-871828-15-5.

- Livingstone, W P (2011). The Life of Robert Laws of Livingstonia: A Narrative of Missionary Adventure and Achievement (Large Print Edition). Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-169-93030-1.

External links

![]() Media related to Robert Laws (1851–1934) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Robert Laws (1851–1934) at Wikimedia Commons