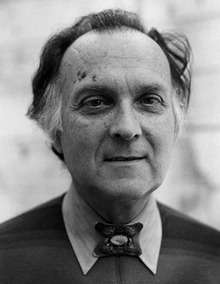

Robert Duncan (poet)

Robert Edward Duncan (January 7, 1919 in Oakland, California – February 3, 1988)[1] was an American poet and a devotee of H.D. and the Western esoteric tradition who spent most of his career in and around San Francisco. Though associated with any number of literary traditions and schools, Duncan is often identified with the poets of the New American Poetry and Black Mountain College. Duncan saw his work as emerging especially from the tradition of Pound, Williams and Lawrence. Duncan was a key figure in the San Francisco Renaissance.

Overview

Not only a poet, but also a public intellectual, Duncan's presence was felt across many facets of popular culture. Duncan’s name is prominent in the history of pre-Stonewall gay culture and in the emergence of bohemian socialist communities of the 1930s and '40s, in the Beat Generation, and also in the cultural and political upheaval of the 1960s, influencing occult and gnostic circles of the time. During the later part of his life, Duncan's work, published by City Lights and New Directions, came to be distributed worldwide, and his influence as a poet is evident today in both mainstream and avant-garde writing.[2]

Birth and early life

Duncan was born in Oakland, California, as Edward Howard Duncan Jr. His mother, Marguerite Pearl Duncan, had died in childbirth and his father was unable to afford him, so in 1920 he was adopted by Edwin and Minnehaha Symmes, a family of devout Theosophists. They renamed him Robert Edward Symmes; it was only after a psychiatric discharge from the army in 1941 that he formed the composite of his previous names and became Robert Edward Duncan.

The Symmeses had begun planning for the child's arrival long prior to his adoption. There were terms for his adoption that had to be met: he had to be born at the time and place appointed by the astrologers, his mother was to die shortly after giving birth, and he was to be of Anglo-Saxon Protestant descent.[3] His childhood was stable, and his parents were popular and social members of their community—Edwin was a prominent architect and Minnehaha devoted much of her time to volunteering and serving on committees. He grew up surrounded by the occult in one form or another; he was well aware of the circumstances of his fated birth and adoption and his parents carefully interpreted his dreams. The family adopted a second child, Barbara Eleanor Symmes, in 1920. She was born one year minus one day after Duncan, on January 6, 1920. She also was selected under circumstances similar to that of her brother; her presence was expected to bring good karma into the family.

At age three, Duncan was injured in an accident on the snow that resulted in his becoming cross-eyed and seeing double. In Roots and Branches, his second major book, he wrote: "I had the double reminder always, the vertical and horizontal displacement in vision that later became separated, specialized into a near and a far sight. One image to the right and above the other. Reach out and touch. Point to the one that is really there."

After the death of his adopted father in 1936, Duncan started studying at the University of California, Berkeley. He began writing poems inspired in part by his left wing politics and acquired a reputation as a bohemian. His friends and influences included Mary and Lilli Fabilli, Virginia Admiral,and Pauline Kael, among others. He thrived as storyteller, poet, and fledgling bohemian, but by his sophomore year he had begun to drop classes and had quit attending obligatory military drills.

In 1938, he briefly attended Black Mountain College, but left after a dispute with faculty over the Spanish Civil War. He spent two years in Philadelphia and then moved to Woodstock, New York to join a commune run by James Cooney, where he worked on Cooney's magazine The Phoenix and met both Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin.

Duncan and homosexuality

|

| Michael Palmer[4] |

While living in Philadelphia, Duncan had his first recorded homosexual relationship with an instructor he had first met in Berkeley, Ned Fahs. In 1941 Duncan was drafted and declared his homosexuality to get discharged. In 1943, he had his first heterosexual relationship, which ended in a short, disastrous marriage. In 1944 Duncan had a relationship with the abstract expressionist painter Robert De Niro Sr.[5]

Duncan's name figures prominently in the history of pre-Stonewall gay culture. In 1944, Duncan wrote the landmark essay The Homosexual in Society. The essay, in which Duncan compared the plight of homosexuals with that of African Americans and Jews, was published in Dwight Macdonald's journal politics. Duncan's essay is considered a pioneering treatise on the experience of homosexuals in American society given its appearance a full decade before any organized gay rights movement (Mattachine Society). In 1951 Duncan met the artist Jess Collins and began a collaboration and partnership that lasted 37 years till Duncan's death.

San Francisco

Duncan returned to San Francisco in 1945 and was befriended by Helen Adam, Madeline Gleason, and Kenneth Rexroth (with whom he had been in correspondence for some time). He returned to Berkeley to study Medieval and Renaissance literature and cultivated a reputation as a shamanistic figure in San Francisco poetry and artistic circles. His first book, Heavenly City Earthly City, was published by Bern Porter in 1947. In the early 1950s he started publishing in Cid Corman's Origin and the Black Mountain Review and in 1956 he spent a time teaching at the Black Mountain College. Robert Duncan in San Francisco by Michael Rumaker, originally published in 2001, tells of this part of Duncan's life.

Mature works

During the 1960s, Duncan achieved considerable artistic and critical success with three books; The Opening of the Field (1960), Roots and Branches (1964), and Bending the Bow (1968). These are generally considered to be his most significant works. His poetry is modernist in its preference for the impersonal, mythic, and hieratic, but Romantic in its privileging of the organic, the irrational and primordial, the not-yet-articulate blindly making its way into language like salmon running upstream:

Neither our vices nor our virtues

further the poem. "They came up

and died

just like they do every year

on the rocks."The poem

feeds upon thought, feeling, impulse,

to breed itself,

a spiritual urgency at the dark ladders leaping.

The Opening of the Field begins with "Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow", suggesting one interpretation of "Field" in the title.[6] The book includes short lyric poems, a recurring sequence of prose poems called "The Structure of Rime," and a long poem called "Poem Beginning with a Line by Pindar". The long poem draws materials from Pindar, Francisco Goya, Walt Whitman, Ezra Pound, Charles Olson, and the myth of Persephone into an extended visionary and ecstatic fugue in the mode of Pound's Pisan Cantos. After Bending the Bow, Duncan vowed to avoid the distraction of publication for fifteen years. His friend and fellow poet Michael Palmer writes about this time in his essay "Ground Work: On Robert Duncan":

| “ | The story is well-known in poetry circles: around 1968, disgusted by his difficulties with publishers and by what he perceived as the careerist strategies of many poets, Duncan vowed not to publish a new collection for fifteen years. (There would be chapbooks along the way.) He felt that this decision would free him to listen to the demands of his (supremely demanding) poetics and would liberate the architecture of his work from all compromised considerations. ...It was not until 1984 that Ground Work I: Before the War appeared, for which he won the National Poetry Award, to be followed in February 1988, the month of his death, by Ground Work II: In the Dark.[7] | ” |

Collected Writings

The Collected Writings of Robert Duncan will begin appearing in January 2011 with the publication of Volume One: The H.D. Book. There will be a total of six volumes including The H.D. Book:--- Early Poems, Plays, and Prose;-- Later Poems, Plays, and Prose;--- Critical Prose--- and two further volumes with contents to be determined.[8]

Notes

- ↑ https://www.loc.gov/item/n79043502/robert-edward-duncan/

- ↑ Robert Duncan Webpage, which is maintained by Duncan biographer and poet Lisa Jarnot.

- ↑ Quoted from Jarnot's biography, excerpts available online at the Robert Duncan Webpage, which is maintained by Duncan biographer and poet Lisa Jarnot.

- ↑ "Robert Duncan and Romantic Synthesis: A Few Notes". This article also republished as "On Robert Duncan" at Modern American Poetry website.

- ↑ Deirdre Bair, Anais Nin (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1995).

- ↑ Cary Nelson, "On 'Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow'", Modern American Poetry. From Our Last First Poets: Vision and History in Contemporary American Poetry, 1981.

- ↑ Michael Palmer, "Ground Work: on Robert Duncan", Jacket 29, April 2006.

- ↑ "UC Press Re-launches The Collected Writings of Robert Duncan", ucpress.edu; accessed June 19, 2015.

Selected bibliography

- Selected Poems (City Lights Pocket Series, 1959)

- Letters 1953-56 (reprint: Flood Editions, Chicago, 2003)

- The Opening of the Field (Grove Press, 1960/New Directions) PS3507.U629 O6

- Roots and Branches (Scribner's, 1964/New Directions)

- Medea at Kolchis; the maiden head (Berkeley: Oyez, 1965) PS3507.U629 M4

- Of the war: passages 22–27 (Berkeley: Oyez, 1966) PS3507.U629 O42

- Bending the Bow (New Directions, 1968)

- The Years As Catches: First poems (1939–1946) (Berkeley, CA: Oyez, 1966)

- Play time, pseudo stein (S.n. Tenth Muse, 1969) Case / PS3507.U629 P55

- Caesar's gate: poems 1949-50 with paste-ups by Jess (s.l. Sand Dollar, 1972) PS3507.U629 C3

- Selected poems by Robert Duncan (San Francisco, City Lights Books. Millwood, NY: Kraus Reprint Co., 1973, 1959) PN6101 .P462 v.2 no.8-14,Suppl.

- An ode and Arcadia (Berkeley: Ark P, 1974) PS3507.U629 O3

- Medieval scenes 1950 and 1959 ( Kent, Ohio: The Kent SU Libraries, 1978) Case / PS3507.U629 M43

- The five songs (Glendale, CA: Reagh, 1981) Case / PS3507 .U629 F5

- Fictive Certainties (Essays) (NY:New Directions, 1983)

- Ground Work: Before the War (NY: New Directions, 1984) PS3507 .U629 G7

- Ground Work II: In the Dark (NY: New Directions, 1987) PS3507 .U629 G69

- Selected Poems edited by Robert Bertholf (NY: New Directions, 1993)

- A Selected Prose (NY: New Directions, 1995)

- Copy Book Entries, transcribed by Robert J. Bertholf (Buffalo, NY: Meow Press, 1996)

- The Letters of Robert Duncan and Denise Levertov (Robert J. Bertholf & Albert Gelpi, eds.) (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004)

- Ground Work: Before the War / In the Dark, Introduction by Michael Palmer (NY:New Directions, 2006)

- The H.D. Book (The Collected Writings of Robert Duncan), Edited by Michael Boughn & Victor Coleman (University of California Press, 2011). ISBN 978-0-520-26075-7

Literature

- Jarnot, Lisa (2012). Robert Duncan: The Ambassador from Venus. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23416-1.

External links

- Works by or about Robert Duncan in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Jess Collins and Robert Duncan Trust

- Robert Duncan reads in 1969 his poem "Structure of Rime IV".

- Duncan at Modern American Poetry

- The Robert Duncan Papers at Washington University in St. Louis

- Ground Work: On Robert Duncan Michael Palmer's "Introduction" to a combined edition of Ground Work: Before the War, and Ground Work II: In the Dark, published by New Directions in April 2006.

- from THE AMBASSADOR FROM VENUS an excerpt of the Duncan biography by Lisa Jarnot

- "The Lure of the God: Robert Duncan on Translating Rilke" see also Rilke

- "Genreading and Underwriting: A Few Soundings and Probes into Robert Duncan's 'Ground Work'" essay by Clément Oudart.

- Robert Duncan's Life and Career

- H.D.Book e-book of unpublished (as of 2006) manuscript by Duncan.

- "Wrath Moves In the Music: Robert Duncan, Laura Riding, Craft and Force in Cold War Poetics" essay by Jeff Hamilton at Jacket Magazine

- Magic & Images/ Images & Magic This piece is by David Levi-Strauss, who studied with Duncan 25 years ago in the short-lived Poetics Program at New College of California in San Francisco that Duncan coordinated from 1980 to 1983.

- Academy of American Poets

Audio links

- The Vancouver 1963 Poetry Conference

- Duncan at PENNsound

- The Academy of American Poets

- Poetry and Literature

- PoetryFoundation.org

- Naropa University Audio Archive