Robert Clayton (bishop)

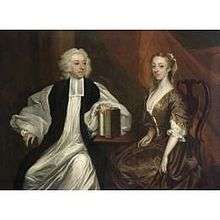

Robert Clayton (1695–1758) was an Irish Protestant bishop, now known for his Essay on Spirit. In his own lifetime he was known for his unorthodox beliefs, which led his critics to question whether he could properly be called a Christian at all, and at the time of his death he was facing charges of heresy.

Life

Clayton was born at Dublin in 1695, a descendant of the Claytons of Fulwood, Lancashire, whose estates came to him by inheritance. He was the eldest of eight children of Dr. Robert Clayton, minister of St. Michael's Church, Dublin, and dean of Kildare, and Eleanor, daughter of John Atherton of Busie. Zachary Pearce educated him privately, at Westminster School.

Clayton entered Trinity College, Dublin, became B.A. 1714, a fellow the same year, M.A. 1717, LL.D. 1722, and D.D. 1730. He made a tour of Italy and France, and on his father's death in 1728 came into possession of a good estate and married Katherine, daughter of Lord Chief Baron Nehemiah Donnellan and his second wife Martha Ussher. He gave his wife's fortune to her sister Anne (who used it to fund the Donnellan Memorial Lectures at Trinity College), and doubled the bequest, under his father's will, to his own three sisters. A wealthy man, he lived in Dublin in what is now Iveagh House.[1] One of the two houses (No. 80) that make up the current Iveagh House was designed for Clayton by Richard Castle, and built in 1736–7.[2]

A gift to a distressed scholar recommended to him by Samuel Clarke brought him Clarke's friendship. Clayton embraced Clarke's Arian doctrines and held to them through life. Queen Caroline, hearing from Clarke of Clayton, had him appointed bishop of Killala and Achonry in 1729-1730. In 1735 he was translated to the diocese of Cork and Ross, and in 1745 to the diocese of Clogher. In 1752 he was made Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, having some years before been elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Last controversies and death

Clayton proposed, 2 February 1756, in the Irish House of Lords, that the Athanasian creed and Nicene creed should be removed from the liturgy of the Church of Ireland.[3] Despite the controversy this aroused, no proceedings were taken against him until the publication of the third part of the 'Vindication of ... the Old and New Testament,' Dublin, 1757, when he renewed his attack on the Trinity and advanced doctrines contrary to the Thirty-nine Articles. Horace Walpole said caustically that his Vindication seemed calculated to destroy anyone's faith in the Testaments. The government, by now seriously alarmed by the heterodoxy of Clayton's opinions, ordered that he be prosecuted for heresy: a meeting of Irish prelates was called at the house of the Primate, and Clayton was summoned to attend. Before the appointed time he died, on 26 February 1758.

Character

Horace Walpole, in a somewhat satirical sketch of the Bishop's life, attributes his death to panic at the thought of having to defend his notions, but acknowledges that he was at least sincere in his beliefs, even if nobody else was able to understand exactly what they were. His wife Katherine Donnellan had a reputation for arrogance: the artist and letter-writer Mary Delaney described her as giving herself "the airs of a Queen" after her husband was made a Bishop.

Works

His first publication was a letter in the Philosophical Transactions, August 1738. In 1739 he published 'The Bishop of Corke's Letter to his Clergy,' Dublin, and 'A Sermon preached before the Judges of Assize,' Cork, and in 1740 'The Religion of Labour,' Dublin, for the Society for Promoting English Protestant Schools in Ireland. In 1743 he published ' A Replication . . . with the History of Popery,' &c., Dublin, directed against the author of 'A Brief Historical Account of the Vaudois.' In 1747 appeared 'The Chronology of the Hebrew Bible vindicated ... to the Death of Moses,' London, pp. 494. In 1749 he published 'A Dissertation on Prophesy . . . with an explanation of the Revelations of St. John,' Dublin; reprinted London. This work aimed at reconciling the Book of Daniel and the Book of Revelation, and proving that the ruin of popery and the end of the dispersion of the Jews would take place in 2000. Two letters followed, printed separately, then together, 1751, London, 'An Impartial Enquiry into the Time of the Coming of the Messiah.'

In 1751 appeared the most notable work written by him (though often asserted to be that of a young clergyman of his diocese), 'Essay on Spirit . . . with some remarks on the Athanasian and Nicene Creeds,' London, 1751. This book, full of Arian doctrine, led to a long controversy. It was attacked by William Jones of Nayland, William Warburton (who described it as 'the rubbish of old heresies'), Nathaniel Lardner, and others. The Duke of Dorset, the lord-lieutenant of Ireland, refused on account of this work to appoint him to the vacant archbishopric of Tuam. Several editions appeared in (1752, 1753, and 1759). In 1752 a work having appeared called 'A Sequel to the Essay on Spirit,' London; Clayton published 'The Genuine Sequel to the Essay,' &c., Dublin.

His next work was 'A Vindication of the Histories of the Old and New Testament, in answer to the Objections of . . . Bolingbroke,' pt. i., Dublin, 1752. In 1753 he published 'A Journey from Grand Cairo to Mount Sinai, and back again. In Company with some Missionaries de propaganda Fide,' &c., translated from a manuscript which had been mentioned by Edward Pococke in his 'Travels.' It included an account of the supposed inscriptions of the Israelites in the Gebel el Mokatab. The work was addressed to the Society of Antiquaries, and the author offered to assist an exploration in Mount Sinai, but the society took no steps in the matter. Edward Wortley Montagu, however, was induced to visit the spot and give an account of the inscriptions. The same year Clayton published 'A Defence of the Essay on Spirit,' London. His next work was 'Some Thoughts on Self-love, Innate Ideas, Freewill,' &c., occasioned by David Hume's works, London, 1754. The same year he brought out the second part of the 'Vindication of ... the Old and New Testament,' Dublin. This produced Alexander Catcott's attack on his theories of the earth's form and the deluge. In 1756 appeared 'Letters which passed between . . . the Bishop of Clogher and Mr. William Penn concerning Baptism,' London, in which he asserted the cessation of baptism by the Holy Ghost. Clayton's friend William Bowyer obtained a copy of the correspondence and published it.

Thomas Barnard, later bishop of Limerick, who married Clayton's niece, and was his executor, had several of his works in manuscript, but they were not published. He gave copyright of all Clayton's works for England to the printer Bowyer, who issued the three parts of the 'Vindication' and the 'Essay on Spirit,' with additional notes and index to the scripture texts, London, 1759.

References

- ↑ Leighton, C. D. A. "Clayton, Robert". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5580. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Google Books.

- ↑ His speech, taken down in shorthand, was then published, and passed through several editions (as late as Evesham, 1839, and London, 1839). It is also given in Jared Sparks, Essays and Tracts on Theology, vol. vi. Boston, 1826.

Further reading

- Nigel Aston, "The Limits of Latitudinarianism: English Reactions to Bishop Clayton's An Essay on Spirit", The Journal of Ecclesiastical History (1998), 49: 407-433.

External links

- Ricorso

- Robert Clayton A Journal from Grand Cairo to Mount Sinai, and back again, Translated from a Manuscript, Written by the Prefetto of Egypt, in company with some Missionaries de propaganda fide at Grand Cairo .... London, 1753. PANDEKTIS (Institute of Neohellenic Research)

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Clayton, Robert". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Clayton, Robert". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.