Research Centre for Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases

The Research Centre for Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases is part of the Pasteur Institute of Iran.

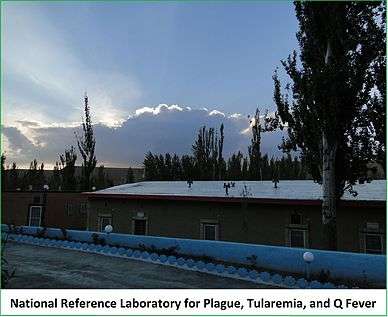

(National Reference Laboratory for Plague, Tularemia, and Q Fever)

The history of the foundation of Pasteur Institute of Iran

One year after World War I and despite the persistent problems caused by casualties and infectious diseases in the country resulting from war, the Iranian government decided to renew its relationship with France to promote medical sciences and research concerning different types of endemic infectious diseases. The Iranian delegates met Pierre Paul Émile Roux, the general director of the Pasteur Institute of Paris, in 1919 and this visit laid the foundation of Pasteur Institute of Iran.

On 20 January 1921, Professor René Legroux, the leading delegate of the Pasteur Institute of Paris, signed a memorandum of understanding with the minister for foreign affairs of Iran and as a result, Pasteur Institute of Iran was established. Pasteur Institute of Iran was the tenth Pasteur Institute formed worldwide.

Moreover, Pasteur Institute of Iran formally started its activity on 23 August 1921. Following Emil Roux's suggestion, Joseph Mesnard was nominated as the first general director of Pasteur Institute of Iran and he served in this position for five years. The second French general director of Pasteur Institute of Iran was Joseph Kerandel, who arrived in Tehran in 1926 and stayed in Iran until the end of his life in 1934. He is buried in the Catholic graveyard in Tehran. This dedicated person devoted his life to the development of Pasteur Institute of Iran, complementing the contribution of his Iranian colleagues Dr Abolghasem Bahrami, Dr. Mehdi Ghodsi, Dr. Hassan Mirdamadi, Dr. Hussein Mashuf, Dr. Ahmad Najm Abadi, Dr. Vartani, Dr. Teymour Dolatshahi, among others; all of these activities led to the advancement of Pasteur Institute of Iran. After Dr. Kerandel’s death, Dr. Hussein Mashuf was nominated general director of Pasteur Institute of Iran. After a year, Professor Legroux was appointed scientific director of Pasteur Institute of Iran on behalf of the Pasteur Institute of Paris. He made several trips to Iran to determine the strategies and supervise the activities of Pasteur Institute of Iran; in his absence, Dr. Abolghasem Bahrami was in charge. Due to World War II, the relationship between the Pasteur Institutes in Iran and Paris was interrupted (from 1939 to 1945); however, the institute continued its activities under the direct supervision of Dr. Bahrami and his deputy, Dr. Ghodsi. Before the war, when the number of laboratories was limited and their activities failed to meet the needs of the country, most of the national health issues related to the ministry of health were addressed by Pasteur Institute of Iran; one of its activities was evaluating the quarantining effectiveness in the country and Pasteur Institute of Iran successfully undertook this important responsibility with the contribution of the authorities at the time (Dr. Ehyaolmolk, Dr. Ehyaolsaltane, Dr. Amiraalam, and Dr. Loghmanolmolk). After World War II, in order to further develop Pasteur Institute of Iran and establish new departments, Dr. Manuchehr Eghbal, the Minister of Health, invited a group of members of the Pasteur Institute of Paris to come to Iran to revise the structures and suggest new strategies. This team, including Dr. Pasteur Valery Radot, the head of the council of the Pasteur Institute of Paris, and other officials visited Iran in 1946; they also participated in the 25th anniversary of the inauguration of Pasteur Institute of Iran. On the 25 August 1946, the complementary agreement of technical and scientific memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the Pasteur Institutes of Iran and Paris was signed. According to this memorandum, Pasteur Institute of Iran was to be formally and financially independent and under the supervision of the minister of health; one of the French experts, Dr. Marcel Baltazard, working in the Pasteur Institute of Morocco, was nominated to be the general director of Pasteur Institute of Iran. According to the new schedule, Pasteur Institute of Iran started a new approach and focusing its activities in the fields of medicine, epidemiology and research; to this end, one important issue was plague studies.

The history of plague in Iran

Iranian physicians were familiar with the human plague for a long time. Although there is little information about the situation of plague from earlier centuries, we have more documented evidence from the 19th and 20th centuries. During the Qajar dynasty (1895 to 1925), cholera and plague were the most frequently documented outbreaks. Such lethal diseases were not hard to imagine considering the poor hygiene and lack of knowledge about the root of transmission, prevention and effective treatment of that time. Several plague outbreaks took place during the Qajar dynasty in Iran. In 1871, a severe form of plague outbreak happened in Saghez and Bane (two cities in Kurdistan province) and the Iranian and non-Iranian physicians, such as Dr. Johan Louis Schlimmer, the instructor in the Darolfonun School, were appointed to control this disease. Dr. Schlimmer noted his observations in his book, "Schlimmer's Terminology", published in 1874.[1] The first Iranian physician who registered his observations about plague using modern medical science was Mohammad Razi Tabatabai, the senior physician in Naser al-Din Shah's army; his book was published under the title "Plague" in 1875. Dr. Joseph Desire Tholozan, (1820 to 1897), the royal physician of Naser Al-din Shah and the head of the ministry of health at that time, evaluated the main and natural foci of plague in Kurdistan between 1870 and 1882 and found certain foci for the disease in various villages of that area.[2][3]

Akanlu and plague

In 1946, together with the new program of activities of Pasteur Institute of Iran, the epidemiology department of Pasteur Institute of Iran started its activities under the supervision of Dr. Baltazard, the general director of the institute. They started their mission in Northwest of Iran and attempted to prepare an epidemiological map of infectious diseases of the country using a portable laboratory in a truck.[4] It later became more practical after they were equipped with professional cars. Although Kurdistan had a history of plague, it was due to the plague outbreak in Kurdistan in the same year that for the first time the research teams were dispatched to an area in which they could control the outbreak via quarantining the foci and epidemiological procedures on the humans and rodents. Studies of the plague foci in this region and the importance of this disease motivated Dr. Baltazard, Dr. Shamsa, Dr. Karimi, Dr. Habibi, Dr. Bahmanyar, Dr. Agha Eftekhari, Dr. Farhang Azad, Dr. Seyyedian and Dr. Majd Teymouri to conduct extensive scientific and epidemiologic studies after educating expert technicians and providing sufficient facilities.[5]

During the nine plague outbreaks in Kurdistan and Azerbaijan between 1946 and 1965, many infected people survived from the disease by the efforts of the dispatched teams of Pasteur Institute of Iran; however, 156 died. In 1952, the first plague laboratory was founded in Akanlu village, near the epicenter of plague in Kurdistan, Iran, on a piece of land bestowed by Manuchehr Gharagozlou, an Iranian friend of Dr. Baltazard. At this research center, currently called "The Research Center for Emerging and Reemerging infectious diseases", Dr. Baltazard and his perseverant colleagues conducted extensive research on plague and established this center as one of the international references for plague. Since 1952, research teams could base themselves in the area for months at a time and conduct detailed research on rodents under more favorable conditions. They were no longer required to carry their equipment throughout their missions. During those years, the integration of field and laboratory collaborations was a key to effective epidemiological actions and led to great research hypotheses. The extensive research by the teams of Pasteur Institute of Iran showed that rodents of the two types Meriones Persicus and Meriones libycus were the main natural reservoirs, unlike their resistance to plague; accordingly, they first proposed that the main reservoir of a disease should be sought amongst the most resistant, not the most sensitive, and such a theory is now accepted as a scientific fact.[4] They also presented their scientific qualifications by publishing several scientific articles.[6][7][8][9] During the development of this research center, many international scientists visited the center, lecturing, studying and/or researching in their fields. In particular, Dr. Xavier Misonne, a Belgian rodentologist who investigated rodent life in Iran[4][10] and Dr. Jean Marie Klein, an entomologist, who conducted extensive research on fleas in the Akanlu center, played important roles.[11][12] In addition, the aerial photographs of Kurdistan and Hamadan were obtained from Iran's army and rodents' locations and the infection were mapped and reported and the first foundations of GIS were set. The research team carefully concentrated on the epizootic trend of the region.[4]

Moreover, it should be noted that the achievements of Pasteur Institute of Iran regarding plague research attracted global attention and such a success motivated them to assign Iranians international plague research. The experts and researchers of Pasteur Institute of Iran, known as WHO experts, continued to conduct related research in many neighboring countries such as Turkey, Syria,[13] Iraq and Yemen,[14] Southeast Asia (India,[15] Indonesia,[16] Thailand), Burma,[17][18] Brazil,[19][20][21][22] and Africa (Zaire, Tanzania);[23] they published all of their research results to be used by others.[15][17][18][19][20][24][25][26][27][28] Most of this research was financially supported by WHO.

In 1972, a WHO meeting on plague was held in this center with many participants from all over the world. Although Dr. Baltazard left Iran in 1962, plague studies continued to be conducted in the following years[28][29][30] in such a way that in 1978 a new focus of the disease was reported in the Sarab region in Eastern Azerbaijan by Dr. Yunos Karimi and his colleagues.[31] It is noteworthy that one of the main responsibilities assigned to Pasteur Institute of Iran and the Akanlu Research Center in the following years was to conduct research about diagnosis and epidemiology of plague. Between 1978 and 2000, missions to monitor the plague in Kurdistan and Hamadan; proved plague infection amongst fleas and rodents in the evaluated regions.Unfortunately, plague research was not seriously continued after 1992 and totally discontinued after 2000, resulting in that Akanlu Research Center, the only research center of Pasteur Institute of Iran on plague, was almost forgotten.

Akanlu Centre and Research on other Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases

Pasteur Institute of Iran has been designated to manage the infectious disease situation in Iran and when taking into account all its completed projects, the Research Center for Emerging and Reemerging infectious diseases can be regarded as the pioneer center for field epidemiology in Iran. The Epidemiology Department of Pasteur Institute of Iran and the Akanlu Research Center did researches on tularemia, recurrent fever, rabies and animal bites in addition to plague studies, the main research field of this center. In addition to close collaborations with other departments of the institute such as parasitology and rabies, the epidemiology department and Akanlu Research Center has conducted research in other fields such as hemorrhagic fevers,[9][32][33] malaria,[34] cholera and small pox. The experts working in this Research Center, as WHO expert, were sent around the world to control outbreaks in addition to performing their important role in controlling a small pox outbreak in this country.

For instance, Dr. Mansur Shamsa was sent to Pakistan to complete a mission on behalf of WHO and Pasteur Institute of Iran; he played an important role in the control of the outbreak in Pakistan.

Studies related to Tularemia

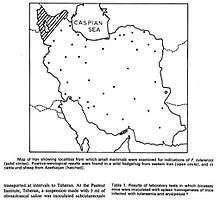

One of the other research fields of the Research Center for Emerging and Reemerging infectious diseases has been running researches on tularemia in Iran. Great research by Dr. Shamsa and his colleagues led to the first report of this disease among the domestic livestock and wildlife in Northwest and Eastern Iran. In this study, more than 4500 wild mammals, 200 sheep and cows were traced for the causative agent of tularemia in 47 locations in Iran. As a result, this study greatly contributed to the identification of wild mammals acting as reservoirs for many zoonotic diseases around the country.[35]

The studies about the epidemiology of tularemia continued in the years thereafter as well. The first report of a human case of tularemia was in 1980 in Marivan, southwestern Kurdistan province.[36]

New period of center’s activity

A new period of research activities focused on the center began in 2010. The results of researches in this period were further reports of plague, tularemia and Q fever in Iran. After decades of lack of reporting about these diseases, the surveillance system of these diseases formed again.

The domain of center’s current activities is defined in three fields: research, education and services. The dedicated laboratories for rodentology studies, serology, molecular studies and culture, seminar halls and guest accommodation (for up to 40 persons) offer a suitable environment for research and education in this region. The center holds the national reference laboratory for plague, tularemia and Q fever, aims to be the WHO collaborating centre in near future and has conducted several studies on emerging and reemerging infectious diseases so far.

A -research activities

A-1 Implementation of research projects

Results of carried out research projects managed by this center includes reports on plague in rodents and dogs in the western part of the country,[37] reports on tularemia seropositivity in human high-risk groups in Kurdistan and Sistan and Baluchestan provinces [38][39] and the first report of endocarditis case of Q fever in Tehran.[40] In addition, this research center has a close scientific relationship with the national reference laboratory of Arboviruses and viral haemorrhagic fever in Pasteur Institute of Iran to monitor other emerging and reemerging infectious diseases such as Crimean Congo haemorrhagic fever,[41][42][43][44][45] dengue fever,[46] West Nile fever,[47][48] Rift Valley fever,[49] etc. To monitor other emerging and reemerging infectious diseases, studies have been done on diseases such as recurrent fever, HIV, tuberculosis and hepatitis.

A-2 Published research results in scientific papers

Published articles from the center’s experts in the field emerging and reemerging infectious diseases are published in more than 120 papers in international journals.

A-3 Collaboration with other related scientific and research centers at home and abroad

The center’s scientific cooperation is in the form of national and international cooperation:

A - 3.1 National cooperation

Currently the center has an agreement of collaboration with the Center of Communicable Diseases Control, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Rodentology Group of Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iranian Association of Microbiology and close collaboration with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences.

A - 3.2 International cooperation

Scientific development and growth of a new phase of scientific activities were beholden to close collaboration with Pasteur Institute of Paris and Pasteur Institute in Madagascar. These two institutes are World Health Organization collaborating centers for plague. The centre has also close collaboration with, National Museum of Natural History, France; Grenoble Alpes University, France; Institute of Pathology and biology in France; Veterinary Medical Research Institute, Hungary; University of Oslo, Norway; Umeå University, Sweden and Kocaeli University, Turkey.

(B) Educational activities

The center’s educational activities are in the form of workshops, implementation of educational courses and internships and apprenticeship courses, guidance and advice for students’ theses and holding journal clubs. From 2011 to 2014 a total of 300 persons from 45 Universities and 120 students from the Universities of Mashhad, Tehran, Hamadan and Pasteur Institute of Iran completed the necessary educational programs in the form of workshops or apprenticeship programs.

B-2 Apprenticeships and internship

A standard program is developed for students to successfully complete different apprenticeship courses in related fields at this center.

(C) Service activities

The following services are performed by the center:

- Investigation and control of emerging and reemerging infectious disease outbreaks through missions around the country

- laboratory services for diagnosis of plague, tularemia and Q fever

- Consultancy to the center for communicable diseases control

C-1 Investigation and control of emerging and reemerging infectious disease outbreaks

Following the center for communicable diseases control’s request, more than 15 missions around the country has been made to control and investigate different outbreaks during the last 3 years.

C-2 Diagnostic Laboratory Services

In December 2014 this center got the certificate to be the National Reference Laboratory for diagnosis of Plague, Tularemia and Q fever. The scope of this laboratory is as follows:

- Tests for bacteria Yersinia pestis including serological tests (ELISA and rapid test), culture (if necessary) and molecular diagnosis based on Real Time PCR for diagnosis of the disease and to monitor the diseases in local, regional and international levels.

- Tests for the bacterium Francisella tularensis including serological test (ELISA and Immunofluorescence), culture (if necessary) and molecular diagnosis by Real Time PCR for detection of the tularemia disease and monitoring the diseases in local, national and international levels.

- Tests for bacteria Coxiella burnetii including serological tests (ELISA and Immunofluorescence), and molecular diagnosis based on Conventional and Real Time PCR for diagnosis the Q fever disease and monitoring of the disease in local, national and international levels.

- Development of standardized diagnostic procedures and requirements related to activities in this area.

- Preparing educational packages, including leaflets, books, guidelines and training CDs.

C-4 Medical Museum

In the repair and rebuilding of the center, a museum was established to house the center’s documents and historical devices.

Center staff

The Research Center employs 4 faculty members, 13 experts and a caretaker either permanently or temporarily.

- Ehsan Mostafavi, DVM, PhD; Associate professor, epidemiologist, Director of the department of epidemiology and Director of the Research Center for Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases

- Abdolrazagh Hashemi Shahraki, PhD; Assistant professor, bacteriologist, Technical head of the National Reference Laboratories for Plague, Tularemia and Q fever.

References

- ↑ Schlimmer, J.L., Terminologie medico-pharmaceutique et anthropologique Francaise-Persane: avec traductions Anglaise et Allemande des termes Français, indications des lieux de provenance des principaux produits animaux et végétaux. 1874: Lithographie d'Ali Gouli Khan.

- ↑ Theodorides, J., Un grand épidémiologiste franco-mauricien: Joseph Désiré Tholoza (1820-1897). Bulletin de la Société de pathologie exotique, 1998. 91(1): p. 104-108.

- ↑ Mollaret, H., [Tholozan and plague in Persia]. Histoire des sciences medicales, 1998. 32(3): p. 297-300.

- 1 2 3 4 Baltazard, M., L'Institut Pasteur de l'Iran vu par. 2004, Theran: Fascicule édité par le service de coopération et d'action culturelle de l'ambassade de France en R I d'Iran à l'occasion de l'inauguration du pavillon Baltazard de l'Institut Pasteur d'Iran.

- ↑ Rezvan H, et al., A preliminary study on the prevalence of anti-HCV amongst healthy blood donors in Iran. Vox Sang, 1994. 67 ((suppl): 100.). 6. Mollaret, H., et al., La peste de fouissement. Bull Soc Pathol Exot, 1963. 56: p. 1186-1193.

- ↑ Mollaret, H., et al., La peste de fouissement. Bull Soc Pathol Exot, 1963. 56: p. 1186-1193.

- ↑ MOLLARET, H., et al. ON THE UREASE OF YERSIN'S BACILLUS. 1964.

- ↑ Baltazard, M., et al., C. Interepizootic conservation of the plague in inveterate reservoir. Hypotheses and work. 1963. Bulletin de la Société de pathologie exotique (1990), 2004. 97: p. 72.

- 1 2 Karimi, Y., et al., Sur le purpura hémorragique observé dans l'Azarbaidjan-Est de l'Iran. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses, 1976. 6(10): p. 399-404.

- ↑ Missone, X., The Cambridge History of Iran, vol. I. The Land of Iran, in Arts asiatiques. 1968, Cambridge University Press. p. 294-304.

- ↑ Sureau, P. and J. Klein, [Arboviruses in Iran (author's transl)]. Médecine tropicale: revue du Corps de santé colonial, 1979. 40(5): p. 549-554.

- ↑ Sureau, P., et al., Isolation of Thogoto, Wad Medani, Wanowrie and Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever viruses from ticks of domestic animals in Iran. Annales de Virologie, E, 1980. 131(2): p. 185-200.

- ↑ Baltazard, M., et al., THE INTEREPIZOOTIC PRESERVATION OF PLAGUE IN AN INVETERATE FOCUS. WORKING HYPOTHESES. Bulletin de la SociÊtÊ de pathologie exotique et de ses filiales. 56: p. 1230.

- ↑ Bahmanyar, M., Human plague episode in the district of Khawlan, Yemen. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 1972. 21(1): p. 123.

- 1 2 Baltazard, M. and M. Bahmanyar, Research on plague in India. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 1960. 23: p. 169.

- ↑ BALTAZARD, M. and M. BAHMANYAR, Research on plague in Java. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 1960. 23: p. 217.

- 1 2 Bahmanyar, M., Assignment report on plague control in Burma, 7–18 November 1970. 1971.

- 1 2 Bahmanyar, M., Assignment report on epidemiology and control of plague in Burma, 9 November 1968-13 April 1969. 1970.

- 1 2 Karimi, Y., C. de Almeida, and A. de Almeida, The experimental plague in rodents in Brazil. Epidemiological deductions. Bulletin de la SociÊtÊ de pathologie exotique et de ses filiales. 67(6): p. 591.

- 1 2 Karimi, Y., M. Eftekhari, and C. de Almeida, On the ecology of fleas implicated in the epidemiology of plague and the possible role of certain hematophagus insects in its transmission in north-east Brazil. Bulletin de la SociÊtÊ de pathologie exotique et de ses filiales. 67(6): p. 583.

- ↑ Karimi, Y., et al. Characteristics of strains of Yersinia pestis isolated in the northeastern part of Brazil.

- ↑ Karimi, Y., et al., Particularités des souches de Yersinia pestis isolés dans le nord-est du Brésil. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol 125A, 1974: p. 213-216.

- ↑ Karimi, Y. and A. Farhang-Azad, [Pulex irritans, a human flea in the plaque infection focus at General Mobutu Lakd region (formerly Lake Albert): epidemiologic significance]. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 1974. 50(6): p. 564.

- ↑ Karimi, Y., C. Rodrigues de Almeida, and F. Petter, Note sur les rongeurs du nord-est du Brésil. Mammalia, 1976. 40(2): p. 257-266.

- ↑ Rust Jr, J., et al., The role of domestic animals in the epidemiology of plague. II. Antibody to Yersinia pestis in sera of dogs and cats. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 1971. 124(5): p. 527-531.

- ↑ BALTAZARD, M. and B. SEYDIAN, Investigation of plague conditions in the Middle East. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 1960. 23: p. 157.

- ↑ Baltazard, M., et al., Kurdistan plague focus. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 1952. 5(4): p. 441.

- 1 2 KARIMI, Y., H. TEYMOYRI, and M. EFTEKHARI, Détermination des foyers natrirels de la peste par I’dtude sérologique chez les renards de l’Iran. Cong. Int. Méd. Trop., AthBnes,, 1973: p. 53.

- ↑ Karimi, Y., Découverte d'un nouveau mésofoyer de peste sauvage dans l'Azerbaidjan oriental de l'Iran. Bulletin Société Pathologie Exotique, 1980. 1: p. 28-35.

- ↑ Karimi, Y., Discovery of a new focus of zoonotic plague in eastern Azerbaijan, Iran. Bulletin de la Societe de Pathologie Exotique et de ses Filiales, 1980. 73(1): p. 28-35.

- ↑ Karimi, Y., M. Mohammadi, and M. Hanif, Methods for rapid laboratory diagnosis of plague and an introdion of a new plague foci in Sarab (East Azarbaijan). Journal of Medical Council, 1978. 6 (4): p. 326-322.

- ↑ Ardoin, A. and Y. Karimi, A focus of thrombocytopenic purpura in East Azerbaidjan province, Iran (1974-1975)(author's transl). Médecine tropicale: revue du Corps de santé colonial. 42(3): p. 319.

- ↑ Mehravarana Ahmad , et al., Molecular detection of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF) virus in ticks from southeastern Iran. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases, 2013. 4: p. 35– 38.

- ↑ Mofidi, C., Epidemiology of malaria and its liquidation in Iran. Meditsinskaia parazitologiia i parazitarnye bolezni. 31: p. 162.

- ↑ Arata, A., et al., First detection of tularaemia in domestic and wild mammals in Iran. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 1973. 49(6): p. 597-603.

- ↑ Karimi Y, Salarkia F, and G. MA, Tularemia: first human case in Iran. Journal of Medical Council of IRAN 1981. 8(2): p. 134-141.

- ↑ Esmaeili, S., et al., Serologic Survey of Plague in Animals, Western Iran. Emerging infectious diseases, 2013. 19(9): p. 1549.

- ↑ Esmaeili, S., et al., Seroepidemiological survey of tularemia among different groups in western Iran. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2014. 18: p. 27-31.

- ↑ Esmaeili, S., et al., Serological survey of tularemia among butchers and slaughterhouse workers in Iran. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 2014. Accepted.

- ↑ Mostafavi, E., S. Esmaeili, and F. Yaghmaie, Q fever endocarditis in Iran: a case report, in The 2nd Iranian congress of Medical Bacteriology. 2013: Tehran, Iran.

- ↑ Mostafavi, E., et al., Temporal modeling of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in eastern Iran. Int J Infect Dis, 2013. 17(7): p. e524-e528.

- ↑ Bokaie, S., et al., Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic fever in northeast of Iran. J Animal Vet Adv, 2008. 7(3): p. 354-361.

- ↑ Mostafavi, E., et al., Seroepidemiological Survey of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Among Sheep in Mazandaran Province, Northern Iran. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 2012. 12(9): p. 739-742.

- ↑ Telmadarraiy, Z., et al., Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: a seroepidemiological and molecular survey in Bahar, Hamadan province of Iran. Asian J Anim Vet Adv, 2008. 3(5): p. 321-327.

- ↑ Mostafavi, E., et al., Spatial Analysis of Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic Fever in Iran. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2013. 89(6): p. 1135-1141.

- ↑ Chinikar, S., et al., Preliminary study of dengue virus infection in Iran. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 2013. 11(3): p. 166-169.

- ↑ Chinikar, S., et al., Seroprevalence of West Nile Virus in Iran. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 2013. 13(8): p. 586-589.

- ↑ Chinikar, S., et al., Detection of West Nile virus genome and specific antibodies in Iranian encephalitis patients. Epidemiology and infection, 2011. 140 (8): p. 1525-1529.

- ↑ Chinikar, S., et al., Surveillance of Rift Valley Fever in Iran between 2001 and 2011. All Research Journal Biology, 2013. 4(2): p. 16-18.