Regelation

Regelation is the phenomenon of melting under pressure and freezing again when the pressure is reduced. Many sources state that regelation can be demonstrated by looping a fine wire around a block of ice, with a heavy weight attached to it. The pressure exerted on the ice slowly melts it locally, permitting the wire to pass through the entire block. The wire's track will refill as soon as pressure is relieved, so the ice block will remain solid even after wire passes completely through. This experiment is possible for ice at −10 °C or cooler, and while essentially valid, the details of the process by which the wire passes through the ice are complex.[1] The phenomenon works best with high thermal conductivity materials such as copper, since latent heat of fusion from the top side needs to be transferred to the lower side to supply latent heat of melting.

If 1 mm diameter wire is used, over an ice cube 50 mm wide, the area the force is exerted on is 50 mm2. This is 50×10−6 m2.

Force (in newtons) equals pressure (in pascals) multiplied by area (in square metres).

If at least 500 atm (50 MPa) is required to melt the ice, a force of (50×106 Pa)(50×10−6 m2) = 2500 N is required, a force roughly equal to the weight of 250 kg on Earth.

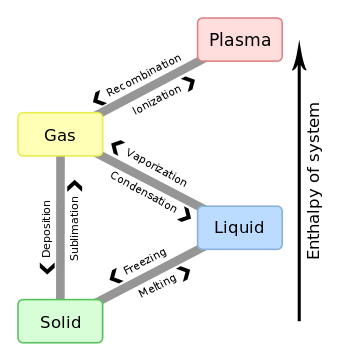

Regelation was discovered by Michael Faraday. Regelation occurs only for substances, such as ice, that have the property of expanding upon freezing, for the melting points of those substances decrease with increasing external pressure. The melting point of ice falls by 0.0072 °C for each additional atm of pressure applied. For example, a pressure of 500 atmospheres is needed for ice to melt at −4 °C.[2]

Surface Melting

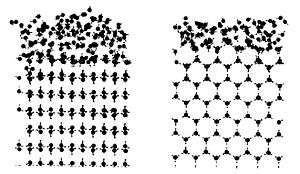

For a normal crystalline ice far below its melting point, there will be some relaxation of the atoms near the surface. Simulations of ice near to its melting point show that there is significant melting of the surface layers rather than a symmetric relaxation of atom positions. Nuclear magnetic resonance provided evidence for a liquid layer on the surface of ice. In 1998, using atomic force microscopy, Astrid Doppenschmidt and Hans Jurgen Butt, measured the thickness of the liquid-like layer on ice to be between 12 nm at −24 °C and 70 nm at −0.7 °C. Surface melting was found to begin at temperatures as low as −33 °C.[3]

The surface melting can account for the following:

- Low coefficient of friction of ice, as experienced by skaters.

- Ease of compaction of ice

- High adhesion of ice surfaces

Examples of Regelation

- A glacier can exert a sufficient amount of pressure on its lower surface to lower the melting point of its ice. The melting of the ice at the glacier's base allows it to move from a higher elevation to a lower elevation. Liquid water may flow from the base of a glacier at lower elevations when the temperature of the air is above the freezing point of water.

Misconceptions

- Ice skating is given as an example of regelation; however the pressure required is much greater than the weight of a skater. Additionally, regelation does not explain how one can ice skate at sub-zero (°C) temperatures.[4]

- Weights suspended from a wire which cuts through ice, is an example given in old textbooks. Once again the pressure required far exceeds the force applied. Conduction of heat from the room through the metal wire is the correct explanation of this phenomenon.

- Compaction and creation of snow balls is another example from old texts. Again the pressure required is far greater than can be applied by hand. A counter example is that cars do not melt snow as they run over it.

Latest Progress

- A supersolid skin that is elastic, hydrophobic, thermally more stable covers both water and ice. The skins of water and ice are characterized by an identical H-O stretching phonons of 3450 cm^-1. Neither the case of liquid forms on ice nor ice layer covers water, but the supersolid skin slipperizes ice and toughnes the water skin[5]

- Hydrogen bond (O:H-O) relaxation under compression. Compression shortens and stiffens the O:H nonbond and simultaneously lengthens and softens the H-O covalent bond, and negative pressure effect oppositely [6]

- Melting point is proportional to the cohesive energy of the covalent bond. Therefore, compression lower the Tm [7]

See also

Further reading

- Y. Huang, X. Zhang, Z. Ma, Y. Zhou, W. Zheng, J. Zhou, and C.Q. Sun, Hydrogen-bond relaxation dynamics: resolving mysteries of water ice. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2015. 285: 109-165.

- C.Q. Sun, Relaxation of the Chemical Bond. Springer Series in Chemical Physics 108. Vol. 108. 2014 Heidelberg,807 pp. ISBN 978-981-4585-20-0.

References

- ↑ Drake, L. D.; Shreve, R. L. (1973). "Pressure Melting and Regelation of Ice by Round Wires". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 332 (1588): 51. Bibcode:1973RSPSA.332...51D. doi:10.1098/rspa.1973.0013.

- ↑ Glossary of Meteorology: Regelation, American Meteorological Society, 2000

- ↑ Physics Today, December 2005, pp. 50–55.

- ↑ White, James. The Physics Teacher, 30, 495 (1992).

- ↑ {{cite journal|last1=Zhang|first1=Xi|title=A common superslid skin covering both water and ice.|journal=PCCP|date=October 2014|volume=16|page=22987-22994|display-authors=etal}.}.

- ↑ Sun, Changqing (2014). Relaxation of the Chemical Bond. Springer. p. 807. ISBN 978-981-4585-20-0..

- ↑ Sun, Chang Qing; et al. (2012). "Hidden force opposing compression of ice". Chem Science. 3: 1455–1460..