Rabbit's foot

In some cultures, the foot of a rabbit is carried as an amulet believed to bring good luck. This belief is held by individuals in a great number of places around the world, including Europe, China, Africa, and North and South America. This belief likely has existed in Europe since 600 BCE[1] amongst Celtic people. In variations of this superstition, the donor rabbit must possess certain attributes, have been killed in a particular place, killed by a particular method, or by a person possessing particular attributes (e.g., by a cross-eyed man).

The rabbit foot charm in North American culture

The belief in North American folklore may originate in the system of African American folk magic known as "hoodoo". A number of strictures attached to the charm that are now observed mostly in the breach:

- First, not any foot from a rabbit will do: it is the left hind foot of a rabbit that is useful as a charm.

- Second, not any left hind foot of a rabbit will do; the rabbit must have been shot or otherwise captured in a cemetery.

- Third, at least according to some sources, not any left hind foot of a rabbit shot in a cemetery will do: the phase of the moon is also important. Some authorities say that the rabbit must be taken in the full moon, while others hold instead that the rabbit must be taken in the new moon. Some sources say instead that the rabbit must be taken on a Friday, or a rainy Friday, or Friday the 13th. Some sources say that the rabbit should be shot with a silver bullet, while others say that the foot must be cut off while the rabbit is still alive.[2]

As a substitute for bones from a human corpse

The various rituals suggested by the sources, though they differ widely one from another, share a common element of the uncanny, and the reverse of what is considered good-omened and auspicious. A rabbit is an animal into which shapeshifting witches such as Isobel Gowdie claimed to be able to transform themselves. Witches were said to be active at the times of the full and new moons.

These widely varying circumstances may share a common thread of suggestion that the true lucky rabbit's foot is actually cut from a shapeshifted witch. The suggestion that the rabbit's foot is a substitute for a part from a witch's body is corroborated by other folklore from hoodoo. Willie Dixon's song "Hoochie Coochie Man" mentions a "black cat bone" along with his mojo and his John the Conqueror: all are artifacts in hoodoo magic. Given the traditional association between black cats and witchcraft, a black cat bone is also potentially a substitute for a human bone from a witch. Hoodoo lore also uses graveyard dust, soil from a cemetery, for various magical purposes. Dust from a good person's grave keeps away evil; dust from a sinner's grave is used for more nefarious magic. The use of graveyard dust may also be a symbolic appropriation of the parts of a corpse as a relic, and a form of sympathetic magic.[2]

In any case, the rabbit's foot is dried out and preserved, and carried around by gamblers and other people who believe it will bring them luck. Rabbit's feet, either authentic or imitation, are frequently sold by curio shops and vending machines. Often, these rabbit's feet have been dyed various colors, and they are often turned into keychains. Few of these rabbit's feet carry any warranty concerning their provenance, or any evidence that the preparers have made any effort to comply with the rituals required by the original tradition. Some may be confected from fake fur and latex "bones" . President Theodore Roosevelt wrote in his autobiography that he had been given a gold-mounted rabbit's foot by John L. Sullivan, as well as a penholder made by Bob Fitzsimmons out of a horseshoe. A 1905 anecdote also tells that Booker T. Washington and Baron Ladislaus Hengelmuller, the ambassador from Austria, got their overcoats confused when they were both in the White House to speak with President Roosevelt; the ambassador noticed that the coat he had taken was not his when he went to the pockets searching for his gloves, and instead found "the left hind foot of a graveyard rabbit, killed in the dark of the moon."[3] Other newspaper stories reported the incident, but omitted the detail about the rabbit's foot.

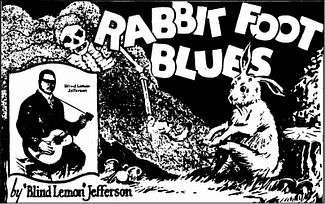

In addition to being mentioned in blues lyrics, the rabbit's foot is mentioned in the American folk song "There'll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight", once popular in minstrel shows; one line goes: "And you've got a rabbit's foot To keep away de hoo-doo".[4]

Humorist R. E. Shay is credited with the witticism, "Depend on the rabbit's foot if you will, but remember it didn't work for the rabbit."[5]

See also

- The Rabbit's Foot Company (also known as the Rabbit's Foot Minstrels)

- Lucky Charms (disambiguation)

- Four-leaf clover

- Horseshoe

References

- ↑ Panati, Charles (1989). Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things. HarperCollins. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- 1 2 Ellis, Bill: Lucifer Ascending: The Occult in Folklore and Popular Culture (University of Kentucky, 2004), ISBN 0-8131-2289-9

- ↑ Harlan, Louis R. The Booker T. Washington Papers Volume 8: 1904–1906. University of Illinois. p. 437. Archived from the original on January 17, 2005. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ↑ Finson, Jon W. (1997). The Voices That Are Gone: Themes in Nineteenth-Century American Popular Song. Oxford University Press. p. 222. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ↑ R.E. Shay quotation.