Psoas major muscle

| Psoas major muscle | |

|---|---|

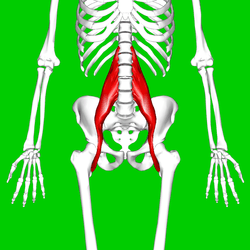

Position of psoas major (shown in red) | |

|

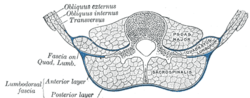

The psoas major and nearby muscles | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Transverse processes of T12-L5 and the lateral aspects of the discs between them |

| Insertion | In the lesser trochanter of the femur |

| Artery | lumbar branch of iliolumbar artery |

| Nerve | Lumbar plexus via anterior branches of L1-L3 nerves |

| Actions | Flexion in the hip joint |

| Antagonist | Gluteus maximus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Musculus psoas major |

| MeSH | A02.633.567.825 |

| TA | A04.7.02.004 |

| FMA | 18060 |

The psoas major (/ˈsoʊ.əs/ or /ˈsoʊ.æs/) (from Greek: psóās, a muscle of the loins) is a long fusiform muscle located on the side of the lumbar region of the vertebral column and brim of the lesser pelvis. It joins the iliacus muscle to form the iliopsoas.

Structure

The psoas major is divided into a superficial and deep part. The deep part originates from the transverse processes of lumbar vertebrae I-V. The superficial part originates from the lateral surfaces of the last thoracic vertebra, lumbar vertebrae I-IV, and from neighboring intervertebral discs. The lumbar plexus lies between the two layers.[1]

The iliacus and psoas major form the iliopsoas, which is surrounded by the iliac fascia. The iliopsoas runs across the iliopubic eminence through the muscular lacuna to its insertion on the lesser trochanter of the femur. The iliopectineal bursa separates the tendon of the iliopsoas muscle from the external surface of the hip joint capsule at the level of the iliopubic eminence.[2] The iliac subtendinous bursa lies between the lesser trochanter and the attachment of the iliopsoas.

Innervation

Innervation of the psoas major is through the anterior rami of L1 to L3 nerves.

Variation

In less than 50 percent of human subjects,[1] the psoas major is accompanied by the psoas minor.

In animals

In mice, it is mostly a fast-twitching, type II muscle,[3] while in human it combines slow and fast-twitching fibers.[4]

This muscle is equivalent to the tenderloin.

Function

The psoas major joins the upper body and the lower body, the axial to the appendicular skeleton, the inside to the outside, and the back to the front.[5] As part of the iliopsoas, psoas major contributes to flexion in the hip joint. On the lumbar spine, unilateral contraction bends the trunk laterally, while bilateral contraction raises the trunk from its supine position.[6]

It forms part of a group of muscles called the hip flexors, whose action is primarily to lift the upper leg towards the body when the body is fixed or to pull the body towards the leg when the leg is fixed.

For example, when doing a sit-up that brings the torso (including the lower back) away from the ground and towards the front of the leg, the hip flexors (including the iliopsoas) will flex the spine upon the pelvis.

Owing to the frontal attachment on the vertebrae, rotation of the spine will stretch the psoas.

Clinical significance

Tightness of the psoas can result in spasms or lower back pain by compressing the lumbar discs.[7] A hypertonic and inflamed psoas can lead to irritation and entrapment of the iliolinguinal and the iliohypogastric nerves, resulting in a sensation of heat or water running down the front of the thigh.

Psoas can be palpated with active flexion of the hip. A positive psoas contracture test and pain with palpation reported by the patient indicate clinical significance. Care should be taken around the abdominal organs, especially the colon when palpating deeply.

The appearance of a protruding belly can visually indicate a hypertonic psoas, which pulls the spine forward while pushing the abdominal contents outward.[8]

Racial variation

Autopsy data show this muscle is thicker in those of African descent than in Caucasians, and that the presence of the psoas minor is also racially variant.[9]

See also

Notes

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- 1 2 3 Platzer (2004), p 234

- ↑ Bojsen-Møller, Finn; Simonsen, Erik B.; Tranum-Jensen, Jørgen (2001). Bevægeapparatets anatomi [Anatomy of the Locomotive Apparatus] (in Danish) (12th ed.). pp. 261–266. ISBN 978-87-628-0307-7.

- ↑ Nunes, MT; Bianco, AC; Migala, A; Agostini, B; Hasselbach, W (1985). "Thyroxine induced transformation in sarcoplasmic reticulum of rabbit soleus and psoas muscles". Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 40 (9–10): 726–34. PMID 2934902.

- ↑ Arbanas, Juraj; Starcevic Klasan, Gordana; Nikolic, Marina; Jerkovic, Romana; Miljanovic, Ivo; Malnar, Daniela (2009). "Fibre type composition of the human psoas major muscle with regard to the level of its origin". Journal of Anatomy. 215 (6): 636–41. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01155.x. PMC 2796786

. PMID 19930517.

. PMID 19930517. - ↑ Earls, J., Myers, T (2010). Fascial Release for Structural Balance. Chichester, England: Lotus Publishing. p. 130. ISBN 9781905367184.

- ↑ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 422

- ↑ Akuthota, et all(2008). p 40

- ↑ Corbo, & Splittberger (2007). Your Body, Your Responsibility. Arizona: Wheatmark Inc, Amazon. p. 88.

- ↑ Hanson, P.; Magnusson, S. P.; Sorensen, H.; Simonsen, E. B. (1999). "Anatomical differences in the psoas muscles in young black and white men". Journal of Anatomy. 194 (Pt 2): 303–307. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.1999.19420303.x.

References

- Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

- Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. 2006. ISBN 1-58890-419-9.

- Akuthota, Venu; Ferreiro, Andrea; Moore, Tamara; Fredericson, Michael (2008). "Core Stability Exercise Principles" (PDF). Current Sports Medicine Reports. American College of Sports Medicine. 7 (1): 39–44. doi:10.1097/01.CSMR.0000308663.13278.69. PMID 18296944. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

Additional images

-

Position of psoas major muscle. Animation. Hip bones are shown in semi-transparent.

-

Horizontal disposition of the peritoneum in the lower part of the abdomen. (Psoas major labeled at bottom left.)

-

Right femur. Anterior surface.

-

Diagram of a transverse section of the posterior abdominal wall, to show the disposition of the lumbodorsal fascia.

-

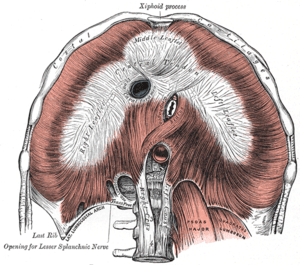

The diaphragm. Under surface.

-

Muscles of the iliac and anterior femoral regions.

-

The arteries of the pelvis.

-

The relations of the femoral and abdominal inguinal rings, seen from within the abdomen. Right side.

-

The thoracic and right lymphatic ducts.

-

The lumbar plexus and its branches.

-

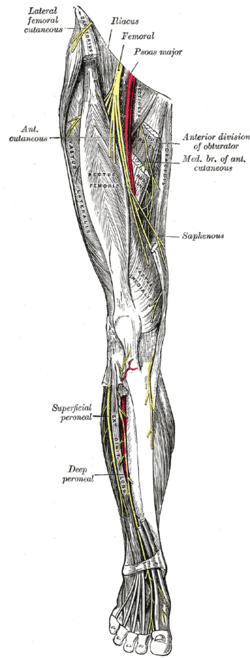

Nerves of the right lower extremity. Front view.

-

Sacral plexus of the right side.

-

Transverse section, showing the relations of the capsule of the kidney.

-

Psoas major muscle

-

Psoas major muscle

-

Psoas major muscle

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Psoas major muscles. |

- -1261436848 at GPnotebook

- Anatomy photo:40:16-0101 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Posterior Abdominal Wall: Muscles of the Posterior Abdominal Wall"

- Anatomy image:8916 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-e12-2 - Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- Psoas Stretches for Back Pain

- Psoas Muscles and Abdominal Exercises for Back Pain