Preaspiration

In phonetics, preaspiration (sometimes spelled pre-aspiration)[1] is a period of voicelessness or aspiration preceding the closure of a voiceless obstruent,[2] basically equivalent to an [h]-like sound preceding the obstruent. In other words, when an obstruent is preaspirated, the glottis is opened for some time before the obstruent closure.[3] To mark preaspiration using the International Phonetic Alphabet, the diacritic for regular aspiration, ⟨ʰ⟩, can be placed before the preaspirated consonant. However, Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996) prefer to use a simple cluster notation, e.g. ⟨hk⟩ instead of ⟨ʰk⟩.

Typology

Preaspiration is comparatively uncommon across languages of the world,[4] and is claimed by some to not be phonemically contrastive in any language.[5] Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996) note that, at least in the case of Icelandic, preaspirated stops have a longer duration of aspiration than normally aspirated (post-aspirated) stops, comparable to clusters of [h]+consonant in languages with such clusters. As a result, they view preaspiration as purely a distributional feature, indistinguishable phonetically and phonologically from clusters with /h/, and prefer to notate preaspirated stops as clusters, e.g. Icelandic kappi /ˈkʰahpi/ "hero" rather than /ˈkʰaʰpi/.

A distinction is often made between so-called normative and non-normative preaspiration: in a language with normative preaspiration of certain voiceless obstruents, the preaspiration is obligatory even though it is not a distinctive feature; in a language with non-normative preaspiration, the preaspiration can be phonetically structured for those who use it, but it is non-obligatory, and may not appear with all speakers.[6][7] Preaspirated consonants are typically in free variation with spirant-stop clusters, though they may also have a relationship (synchronically and diachronically) with long vowels or [s]-stop clusters.[8]

Preaspiration can take a number of different forms; while the most usual is glottal friction (an [h]-like sound), the precise phonetic quality can be affected by the obstruent or the preceding vowel, becoming for example [ç] after close vowels;[9] other potential realizations include [x][8] and even [f].[10]

Preaspiration is very unstable both synchronically and diachronically and is often replaced by a fricative or by a lengthening of the preceding vowel.[11]

Distribution

Preaspiration is perhaps best known from North Germanic languages, most prominently in Icelandic and Faroese, but also some dialects of Norwegian and Swedish. It is also a prominent feature of Scottish Gaelic. The presence of preaspiration in Gaelic has been attributed to Scandinavian influence.[12] Within Northwestern Europe preaspiration is furthermore found in most Sami languages. Preaspiration is absent from Inari Sami, where it has been replaced by postaspiration.[13] The historical relationship between preaspiration in Sami and Scandinavian is disputed: there is general agreement of a connection, but not on whether it represents Sami influence in Scandinavian, or Scandinavian influence in Sami.

Elsewhere in the world, preaspiration occurs in Halh Mongolian and in several American Indian languages, including dialects of Cree, Ojibwe, Fox, Miami-Illinois, Hopi[14][15][16][17] and Purepecha.

Examples

English

In certain accents, such as Geordie (among younger women)[18] and in some speakers of Dublin English[19] word- and utterance-final /p, t, k/ can be preaspirated.[18][19]

Faroese

Some examples of preaspirated plosives and affricates from Faroese (where they occur only after stressed vowels):

- klappa [ˈkʰlaʰpːa], 'clap'

- hattur [ˈhaʰtːʊɹ], 'hat'

- takka [ˈtʰaʰkːa], 'thank'

- søkkja [ˈsœʰt͡ʃːa], 'sink' (transitive)

Furthermore, the dialects of Vágar, northern Streymoy and Eysturoy also have ungeminated preaspirated plosives and affricates (except after close vowels/diphthongs):

- apa [ˈɛaːʰpa], 'ape', but: vípa [ˈvʊiːpa], 'northern lapwing'

- eta [ˈeːʰta], 'eat', but: hiti [ˈhiːtɪ], 'heat'

- vøka [ˈvøːʰka], 'wake', but: húka [ˈhʉuːka], to 'squat'

- høkja [ˈhøːʰt͡ʃa], 'crutch', but: vitja [viːt͡ʃa], to 'visit'

Icelandic

Some examples of preaspirated plosives from Icelandic (where they occur only after stressed vowels):[20]

- kappi [ˈkʰaʰpi], 'hero'

- hattur [ˈhaʰtʏr], 'hat'

- þakka [ˈθaʰka], 'thank'

Huautla Mazatec

In Huautla Mazatec, preaspirates can occur word-initially, perhaps uniquely among languages which contain preaspirates:[21]

- [ʰti] - 'fish'

- [ʰtse] - 'a sore'

- [ʰtʃi] - 'small'

- [ʰka] - 'stubble'

Sami languages

Preaspiration in the Sami languages occurs on word-medial voiceless stops and affricates of all places of articulation available: /p/, /t̪/, /t͡s/, /t͡ɕ/, /k/. In the Western Sami languages (Southern, Ume, Pite, Lule and Northern) as well as Skolt Sami, preaspiration affects both long and half-long consonants; in most Eastern Sami languages (Akkala, Kildin and Ter) only fully long consonants are preaspirated. This likely represents two waves of innovation: an early preaspiration of long consonants dating back to Proto-Sami, followed by a secondary preaspiration of half-long consonants that originated in the Western Sami area and spread eastwards to Skolt Sami.[22]

In several Sami languages, preaspirated stops/affricates contrast with lax voiceless stops, either due to denasalization of earlier clusters (e.g. *nt > [d̥ː]) or in connection to consonant gradation.

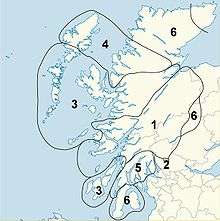

Scottish Gaelic

In Scottish Gaelic, however, due to the historical loss of voiced stops preaspiration is phonemic in medial and final positions after stressed vowels.[23]

Its strength varies from area to area and can manifest itself as [ʰ] or [h] or in areas with strong preaspiration as [ç] or [x]. The occurrence of preaspiration follows a hierarchy of c > t > p; i.e. if a dialect has preaspiration with /pʰ/, it will also have it in the other places of articulation. Preaspiration manifests itself as follows:[24]

- Area 1 as [xk xt xp] and [çkʲ çtʲ çp]

- Area 2 as [xk xt hp] and [çkʲ çtʲ hp]

- Area 3 as [xk ht hp] and [çkʲ htʲ hp]

- Area 4 as [ʰk ʰt ʰp]

- Area 5 as [xk] and [çkʲ] (no preaspiration of t and p)

- Area 6 no preaspiration

There are numerous minimal pairs:

- glag [klˠ̪ak] "clock" vs glac [klˠ̪axk] "grab" (v.)

- ad [at̪] "hat" vs at [aht̪] "boil" (n.)

- leag [ʎɛk] "throw down" vs leac [ʎɛxk] "flagstone"

- aba [apə] "abbot" vs apa [ahpə] "ape" (n.)

h-clusters

Although distinguishing preaspirated consonants from clusters of /h/ and a voiceless consonant can be difficult, the reverse does not hold: there are numerous languages such as Arabic or Finnish where such clusters are unanimously considered to constitute consonant clusters.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Nance & Stuart-Smith (2013)

- ↑ Silverman (2003:575)

- ↑ Stevens & Hajek (2004:334)

- ↑ Silverman (2003:592)

- ↑ Tronnier (2002:33)

- ↑ Gordeeva & Scobbie (2007:?)

- ↑ McRobbie-Utasi (2003:1)

- 1 2 Silverman (2003:593)

- ↑ Stevens & Hajek (2004:334–35)

- ↑ McRobbie-Utasi (1991:77)

- ↑ Silverman (2003:592, 595)

- ↑ Oskar Bandle, Gun Widmark. The Nordic Languages. p. 2059.

- ↑ Sammallahti (1998:55)

- ↑ Rießler (2004:?)

- ↑ McRobbie-Utasi (1991:?)

- ↑ McRobbie-Utasi (2003)

- ↑ Svantesson (2003:?)

- 1 2 Watt & Allen (2003:268)

- 1 2 "Glossary". Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ↑ Silverman (2003:582)

- ↑ Silverman (2003:590–91)

- ↑ Sammallahti (1998:193)

- ↑ Borgstrøm, C. The Dialects of the Outer Hebrides (1940) Norsk Tidskrift for Sprogvidenskap

- ↑ Ó Dochartaigh, C. Survey of the Gaelic Dialects of Scotland I-V Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies (1997) ISBN 1-85500-165-9

References

- Gordeeva, Olga; Scobbie, James M (2007), Non-normative preaspirated voiceless fricatives in Scottish English: Phonetic and phonological characteristics. (PDF), retrieved 2016-07-22

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996), The Sounds of the World's Languages, Oxford: Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-19814-8

- McRobbie-Utasi, Zita (1991), "Preaspiration in Skolt Sámi", in McFetridge, P., SFU Working Papers in Linguistics (PDF), 1, pp. 77–87, retrieved 2007-03-07

- McRobbie-Utasi, Zita (2003), Normative Preaspiration in Skolt Sami in Relation to the Distribution of Duration in the Disyllabic Stress-Group (PDF), retrieved 2007-03-07

- Nance, Claire; Stuart-Smith, Jane (2013), "Pre-aspiration and post-aspiration in Scottish Gaelic stop consonants", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 43 (2): 129–152, doi:10.1017/S0025100313000042

- Rießler, Michael (2004), "On the origin of preaspiration in North Germanic", in Jones-Bley, Karlene; Della Volpe, Angela; Dexter, Miriam Robbins; Martin E., Huld, Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual UCLA Indo-European Conference. Los Angeles, November 7–8, 2003 (PDF), Journal of Indo-European Monograph Series, 49, Washington, D.C.: Institute for the Study of Man, pp. 168–185, archived from the original (PDF) on September 6, 2006, retrieved 2007-03-07

- Sammallahti, Pekka (1998). The Saami Languages: An Introduction. Davvi Girji.

- Silverman, Daniel (2003), "On the Rarity of Pre-Aspirated Stops", Journal of Linguistics, 39 (3): 575–598, doi:10.1017/S002222670300210X, retrieved 2007-03-08

- Stevens, Mary; Hajek, John (2004), "How Pervasive is Preaspiration? Investigating Sonorant Devoicing in Sienese Italian", Tenth Australian International Conference on Speech Science & Technology, Macquarie University, Sydney (PDF), pp. 334–39, retrieved 2007-03-07

- Svantesson, Jan-Olof (2003), "Preaspiration in Old Mongolian?", Proceedings from Fonetik 2003. PHONUM. Reports in Phonetics (PDF), 9, Umeå University, pp. 5–8, retrieved 2007-03-07

- Tronnier, Mechtild (2002), "Preaspiration in Southern Swedish Dialects", Proceedings of Fonetik 2002. Speech, Music and Hearing Quarterly Progress and Status Report (PDF), 44, pp. 33–36, retrieved 2007-03-07

- Watt, Dominic; Allen, William (2003), "Tyneside English", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 33 (2): 267–271, doi:10.1017/S0025100303001397